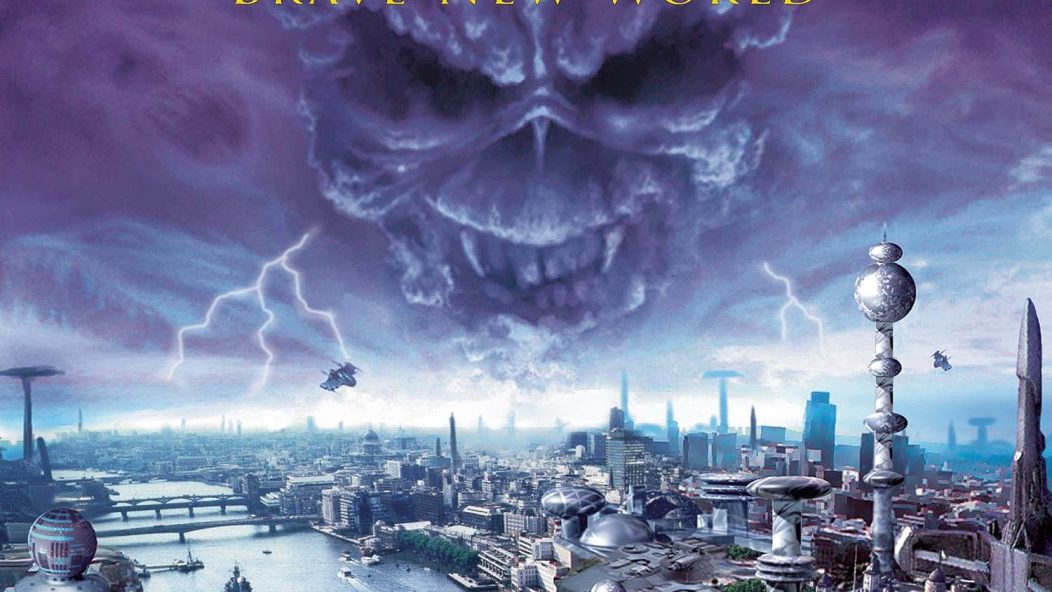

Iron Maiden's Prog-Soaked "Brave New World" Still Invincible 20 Years On

…

The Power Began to Boil

…

Full disclosure: Brave New World is my favorite Iron Maiden album.

I don’t say “best” and that’s for a reason; not to knock the album, which I think would be cowardly on my part if that was my intent, but because the entire idea of what constitutes the best Iron Maiden album is a fascinating and fruitful discussion. The group certainly has a golden age, those first seven iconic records that provided so, so much for the broad world of heavy metal and hard rock, but there is a secondary undercurrent to their career of a group perpetually striving to be a progressive rock band even despite the blockages in their paths over the course of time.

Their early material is driven by a verve and energy often at odds with their more sophisticated dreams, a gradient which gradually gave way over the course of their careers as their energy level slowly waned and their technical and compositional sophistication slowly increased.

Brave New World is certainly a departure in many ways from that iconic sound the group created, but it also reads as perhaps the first moment their precise vision of what progressive rock and progressive metal under the Iron Maiden banner might look like, functioning as a second debut record for a group already decades into its career. There is something to appreciate there, whether you are one of the converted die-hards of the post-reunion era like me or even if you still strongly prefer that magical first run.

Iron Maiden is an interesting band from a critical perspective for a number of reasons. One of the biggest ones is how puzzling it is to decide what if any of their catalog qualifies as their best work. Powerslave is an early favorite and for good reason: the opening two-fer salvo of “Aces High” and “2 Minutes To Midnight” is one of the greatest in heavy metal’s history and its closing two epics “Powerslave” and the inestimable “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” are likewise a great argument for the mightiest ending of an album in the history of the 20th Century. But you still have The Number of the Beast to contend with, which not only has top-shelf songwriting across the whole record (save, perhaps, late-album track “Gangland”) as well as rightful hall-of-famers like the title track, “22 Acacia Avenue,” and “Run to the Hills” — it also has arguably the greatest heavy metal song of all time in album closer “Hallowed Be Thy Name.”

Powerslave and The Number of the Beast don’t contain the ragged punk/prog/heavy metal mutant hybrid energy of Killers or Iron Maiden, though, nor do they contain the hardened-crystal prog/pop perfection of Seventh Son of a Seventh Son. There’s a not-unsizeable contingent of people who swear on the minor adjustments found on Piece of Mind or the bomb-bursting creative spark of the addition of synths and more explicitly prog songwriting on Somewhere in Time as candidates for greatest… and, well, it quickly becomes apparent that Iron Maiden requires a more subtle and sophisticated approach to parsing their mighty and rightly-adored catalog.

Because, lest we forget, Iron Maiden is not just a heavy metal band but, along with Judas Priest, Black Sabbath, and that magical first four from Metallica, indisputably one of the absolute greatest of all time. That first run from their debut up to Seventh Son are not just good or even great records; they are legendary, each and every one, with each record containing some of the absolute finest and most influential songs of the entire genre. They were never the flashiest or most technically proficient band, nor the most extreme, and despite their lavish stage sets and commitment to the pure theater of heavy metal they were also never as purely theatrical as, say, Operation: Mindcrime-era Queensryche or others. Iron Maiden didn’t try to always break ground; what they focused on instead was the art of perfection.

Those first seven albums were largely a product of a band full of ambition making the best of what they had available at the time. In a way, we are lucky they were limited and youthful as they were; the punkish energy of their first two albums, every second of lightning-fast harmonized licks feeling like they might fall right off the edge but never quite collapsing, would never have come about if they had they chops to dive immediately into full-on Tales From Topographic Oceans progressive rock — it was that sense of compensating youthful energy that became a defining staple of their first run. But the itch toward more broadly progressive material had been there from the beginning: songs like “Phantom of the Opera” and “Transylvania” from the debut hint at a band beginning to explore not just the fullness of their songwriting ability but also testing their compositional limits, making the first tentative stabs at this image lurking within the group.

These experiments would continue across future records, from the two instrumentals “The Ides of March” and “Genghis Khan” from Killers to the album closing progressively-structured “Hallowed Be Thy Name.” Piece of Mind showed the first signs of the group integrating these progressive compositional conceits into the fabric of their other songwriting ideas, producing the group’s iconic melodic lite prog approach to heavy metal in full for the first time.

…

…

But it was Powerslave‘s final two tracks, and album closer “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” especially, that was the moment the doors blasted off the hinges entirely. The group had integrated longer and more convoluted instrumental explorations in the middle of songs before, with the middle passage of “Where Eagles Dare” being the previous high-point of the band exploring progressive terrain within the songforms they had mastered, but “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” was something else entirely. Its 14-minute span felt as radically eruptive for the band in terms of songwriting as the opening track of the third Yes recordThe Yes Album. It isn’t just the scope or span of the song, either; the sections were both well-balanced and well-delineated, with a plethora of moods and timbral explorations as opposed to a singular melodic conceit recontextualized over double-digit minute lengths.

The point is that “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” was every bit as good as the prog epics they had idolized from the bands they, and especially functional bandleader Steve Harris, worshipped. It was delivered on the same record as (relatively) more straightforward fare e.g. “Aces High” and “Flash of the Blade,” meaning to some that the group had finally mastered a difficult balance. In retrospect, this was instead the moment the band gathered up its courage to dive deeper than it ever had before.

The span from Powerslave up to the creation of Brave New World reads as the fallout of that one momentous track. The band finally incorporated synths on their following record Somewhere in Time and in turn enhanced the prog elements in the songwriting formalism they had tapped into on Piece of Mind, producing their most fully balanced prog/metal album up to that point. Seventh Son of a Seventh Son was one step further, ironically in both directions, being the band’s first concept record and first stab at an epic on the same scope and scale as the preceding masterwork “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” while also sharpening their pop hooks and melodicism.

This sharpening of the pop impulse proved to be as rupturing as that first prog masterwork, with No Prayer for the Dying being a radical step back to focus on pop-minded directness in the wake of what the group felt was an increasingly unreachable height. (This instinct, it should be noted, is one vindication for those who do not favor the post-reunion era’s turn to explicitly prog metal, where the band seemed to view even Seventh Son of a Seventh Son as beginning to push things perhaps too far.) This redirection lost them Adrian Smith, who felt that their long-sought progressive arc was beginning to blossom just as it was killed; the album that followed, Fear of the Dark, showed a band seemingly scatterbrained after the rise of grunge, producing an album of mixed quality and limited vision that likewise cost them Bruce Dickinson.

The following two albums The X Factor and Virtual XI showcased a band tentatively relearning their formerly progressive-leaning songwriting idiom. The results were historically rocky, with little success at the time despite major buzz around them at the time, with critics absolutely panning the records and fans having a lukewarm response. They remain, however, pivotal records in the tale of Brave New World; just as “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” was a long-pressaged fully prog-rock epic that laid the foundation for their future direction, The X Factor and Virtual XI showed a band finally returning to the work they’d more or less abandoned after Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, albeit adjoined with the darkness and mid-paced explorations of passages from No Prayer for the Dying and especially the grit of Fear of the Dark.

Blaze Bayley’s tenure had been mercifully cut short; despite being an excellent vocalist, they never seemed to learn how to write material fit for his range, and later performances of a returned Bruce Dickinson performing his material slowly won back critical interest in the records even if it didn’t suddenly make them darkhorse favorites. But the songwriting idiom of their post-reunion period can be seen across The X Factor and Virtual XI in its prototypical form, with epics like “Sign of the Cross,” “The Angel and the Gambler,” and “The Clansmen” being almost structurally identical to the approach of songwriting that would be showcased on Brave New World.

…

A Brave New World

…

Brave New World was the sound of a band reenergized. From the thunderous opener “The Wicker Man” to the mid-paced grandeur of “Ghost of the Navigator” and “Brave New World” — from the emotionally-riveting progressive masterwork of “Blood Brothers” to the slow and ponderous epics of the middle span — from the sudden burst of late-album energy in “Out of the Silent Planet” and the macro-scale epic of album-closer “The Thin Line Between Love and Hate” — Brave New World showcases a band reaching to explore the full potentialities of their new three-guitar lineup and the obvious excitement the players feel being back together.

Vocalists are hard to replace not just because of their iconic timbres (no doubt an important element by its lonesome) but also because over years and decades players often find themselves writing for a particular kind of voice the players associate with the group. The band certainly seems to pitch their songwriting around Bruce’s voice; just see how naturally the songs here seem to cradle his impressive, powerful and supple voice, especially compared to how uncomfortable some of the vocal arrangements seemed to lay against the instrumentals during the Blaze Bayley years.

There is a singular persistent charm to Bruce Dickinson’s voice against the instrumentals of Iron Maiden that is maintained on Brave New World, seemingly almost effortless, a peerless and perfect match of voice and music that is only matched by fellow metal gods Rob Halford and Ronnie James Dio in their respective bands. The songs are admittedly not far removed from the Bayley-era songwriting, but aside from the obvious shift of vocalists suddenly making things seem more comfortable, there is one other key change: Adrian Smith.

While Dickinson’s return provides the most obvious timbral shift of the group on Brave New World, it is the subtle but pervasive shift in sound that Adrian Smith brings that feels the most profoundly transformative for the record and indeed for the past 20 years of Iron Maiden music as a whole. Smith simply feels the most commensurate songwriting partner for Steve Harris that Harris has ever known, knowing with seeming extrasensory perception the precise arrangement touches to bring out the full richness and power of Harris’ ideas. Murray is perhaps the more accomplished soloist and melodic writer and Jannick Gers produces a meat and heft with his playing the otherwise youthful and nimble Iron Maiden lacked before his incorporation, but Adrian Smith’s intuitive grasp of what a progressive Iron Maiden might sound like, evidenced on records such as Somewhere in Time and Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, feels like the most obvious shift between Brave New World and Virtual XI.

…

…

Take for instance the instrumental middle passage of “The Nomad,” a song originally written during the Virtual XI sessions, and compare it to “The Clansman”, the big epic from that record. There is a similar sensibility, showing clear lineage, where the energy drops way, way down into a foggy, mist-strewn crawl through maudlin terrain, bass alternating notes in a diad while a melodic and lyrical guitar line sings across. The difference isn’t in approach but in fullness, the comparative heft and roar of the slow build in “The Nomad” versus the eerie spaciousness of “The Clansman”, itself perhaps the best track from that ill-fated earlier record.

The presence of three guitarists, each with very different characters, allowed certain arrangement tricks that weren’t possible before, Harris’ trademark bass rumble providing the backbone abetted by Gers’ hefty chug, Murray’s lyrical turns of phrase and Smith playing upper harmonies, all placed against the space-filling subtle synths all over the record. Adrian Smith’s greatest gift to the band had always been his harmonic gifts, offering the occasional dash of more interesting and fulfilling chordal ideas that in the triple-guitar lineup were finally able to become his primary focus, allowing the more delicate and progressive passages of the record to suddenly span out with four different string voices before crashing back together into a unified wall of sound for the heavier and more anthemic portions.

Heavy metal, to me, has always been an outgrowth of and interrelation to the space between prog, hard rock, and psychedelia, with the adventurousness of early groups like Black Sabbath’s notoriously jammy debut, Judas Priest’s penchant for wild multi-part epics early on, and Rainbow’s heavy prog rock being functional templates of the style that future groups would always have to contend with. It is from this space that I tend to approach Iron Maiden, a group that even on their earliest and rawest material strikes me as a progressive metal band struggling to make itself known against their own limitations, with the struggle itself being the fundament of their most unassailable and universally-beloved material.

You can feel the lightning-strike blood-sweat-and-tears furious energy of those first seven records, the band battling for their life with ever-increasing technical and songwriting chops, cutting closer and closer to the perfect culmination of hard rock, heavy metal, and prog they clearly had always held dear in their hearts. Iron Maiden live for me alongside groups like Saracen, Dark Quarterer and Queensryche, groups that always were on the cusp of tricking headbanging heavy metal ghouls and hooligans into listening to Gabriel-era Genesis and the placid and beautiful epics Tony Banks penned for that group.

Iron Maiden, and Steve Harris in particular, always seemed drawn to that sense of paced regality that classic-era prog rock embraced so deeply, living most comfortably in mid-paced and immaculately detailed tapestries. This is, after all, one of the biggest influences on Dream Theater, an interrelation strengthened by their choice of Kevin Shirley as producer for this record coming hot off the heels of his work on Dream Theater’s own career masterwork Metropolis Pt. 2: Scenes From a Memory. Brave New World is a fulfillment of that interior image of the band, one that many fans seem to struggle with, desiring the group to return to an image we as listeners feel more central to the group’s identity but which the band seems to view as evolutionary rather than purely defining.

It is no coincidence that the group post-Brave New World have lived so solidly within those aesthetic realms, exploring that space for 20 years now, a span of time equal to the various evolutionary twists and turns of the group’s career prior. It is hard not to read that as intentional; Brave New World is how the band see themselves at their brightest effulgence, whether any given listener or critic may agree with that assessment.

I am sympathetic to critique of the record, however. It is certainly a more shall we say paced record than previous Iron Maiden albums, not only being their second longest at the time but also largely living within the same BPM range. The group doesn’t feel sluggish per se, and they certainly have stretches where they punch up the speed of things a good bit, but the days of the relatively-blazing “The Trooper” were certainly gone. In a way, the group invited this critique on themselves — the album title Brave New World certainly signifies a change of things or at least a fulfillment of things latent for years, but by keeping the same band name and returning to the classic lineup, it does unfortunately invite comparison to records such as Piece of Mind and Powerslave, records that Brave New World certainly bears some similarity to but ultimately feels quite different from.

There is an alternate world where the past 20 years of Iron Maiden music, from Brave New World on, was released under a different name, signifying their shift toward more purely progressive metal waters. That kind of thing wouldn’t stop comparison completely, obviously, but would go further in acknowledging that while Brave New World is a genetic fulfillment of ideas, sounds, and methods explored by Iron Maiden for decades prior, it assembles into something quite different from songs such as “Wrathchild” or “Aces High” with seemingly little interest in returning to those sonic spaces.

To give full and fair voice to its critics, former Invisible Oranges Editor-in-Chief Ian Cory wrote an excellent article grappling with some of the frustrations of the rhythmic elements of later-period Iron Maiden starting with Brave New World.

…

…

My final bid in defense of Brave New World, my very favorite Iron Maiden album, comes from the song “Blood Brothers.” I am well aware that my personal view that this is the greatest song the group ever penned would be met with admittedly rightful derision; after all, seriously attempting to convince people it is somehow better than career-defining songs like “Hallowed Be Thy Name,” “Where Eagles Dare,” “The Trooper,” and “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” would be a fools’ errand.

But “Blood Brothers” has two things that at least puts it comfortably in the company of those earlier songs. The first is its arrangement, easily the best of the prog-rock era of Iron Maiden, which with its layers of dappling guitars and thoughtful melodic pacing finally sees the band undeniably achieving the sense of grace and grandeur they gesture to across this record and more broadly in their prog-rock period. The layers of guitars, orchestra, and synth are deployed slowly, revealing themselves only on close scrutiny, the little twists and touches of buried guitar tracks and pizzicato strings feeling like an unending bevy of sonic richness and depth. This is married against a lilting elegiac and moving melody, perhaps the closest the band has ever gotten to the hand-on-heart forthright emotionalism of musical theater ala Les Miserables or the like.

The second strength of this song is tied to that last point: it is easily the most emotionally powerful and salient song Iron Maiden have ever written, and for damn good reason. Steve Harris famously penned the song in response to the loss of his father, building it from a seed of grief into broader ruminations. He gestures for the further thing, a confrontation with the aimless and answerless questions of grief, loss, and reflections of the arc of a life bound up with commitment to care and those we love in our lives. It sounds undeniably trite on paper but, for those who have lost a parent, sibling, spouse, or child, or even just a close enough friend, those kinds of real and grounded ruminations on the complexity of grief and the yearning of that loss produce a seemingly inexhaustible power. My love of the song predated the loss of friends and my father, but those experiences solidified its estimation in my mind.

I love Iron Maiden, as any good and true metalhead should, but there’s little else in their catalog that gives me daggers in the heart the way “Blood Brothers” does.

The album is not merely great due to one track. As much as the album-length commitment over almost 70 minutes to mid-paced work can be tiring to some, from another perspective it creates a profound sense of aesthetic unity to the record, where the similar pacings combined with keen sequencing makes the record play out more like a vast and gestural conceptual piece or song-suite rather than a loose collection of unrelated tracks. The movement of “Blood Brothers,” a paean of grief that expands into the kinds of gloomy and answerless existential ponderings of someone subsumed in grief, into “The Mercenary,” with its chorus of “Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide / You’ve got to kill to stay alive / Show them no fear, show them no pain” feels entirely smooth.

If there is a broad conceptual arc to Brave New World buried inside, it is that of the unique losses and sense of ungrounding that comes in middle age as parents die, old relationships wither, and a new world is born endlessly before you, the realization dawns that you aren’t the first person this experience has happened to and won’t be the last. I don’t think any great or deliberate lyrical thread is strung through these songs, but the emotional timbres and shifting sensations of their verses and choruses have gradually caused them over the past 20 years of listening to Brave New World to cohere into a single complex breath.

It’s that last part that makes Brave New World my favorite Iron Maiden album.

…

Coda

…

As I said before, I don’t think one can easily pluck out a “best” for Iron Maiden. One of the most interesting aspects about Iron Maiden is its fandom both within critics and listeners finds almost all of their albums at some point seriously argued as their best which gradually leads to the dawning realization that we are really talking about favorites, the false image of the objective “best” falling away for the more salient and tangible subjective “favorite.”

We all have our Iron Maiden albums, be they Killers or Piece of Mind or Seventh Son of a Seventh Son; a close friend of mine swears by A Matter of Life and Death and, having heard his impassioned arguments for why he adores it so much, I see a great sense of logic in what he says.

But for me, it’s Brave New World. I watched Iron Maiden music videos laying flat on my back in my parents’ room late at night growing up, sneaking in on nights when I couldn’t get to sleep, only to pluck the remote of their always-on television from the middle of their queen-sized bed, change the channel to VH1 (which consistently played metal and heavy rock videos late at night). My thirst for heavy metal came in no small part to those hours of boredom and childhood insomnia, where videos such as the black-and-white nightmare-fest that was Alice in Chains’ “Man in the Box” alongside the chest-thumping hypermasculine freedom of Judas Priest’s “Heading Out to the Highway” provided psychic roadmaps for my young impressionable mind.

It was there that I saw the videos for such Iron Maiden classics as “Where Eagles Dare” and “The Flight of Icarus,” the midnight hour and darkly epic gestures of their music and seductive barbarian visions of their music videos producing an alluring sense of danger and mysticism that I fear heavy metal may not have had for me had I discovered it in a mall or a radio. I knew the band’s name, knew their esteem, heard their name bandied about next to groups I already idolized like Metallica and Megadeth, my very first heavy metal bands I ever loved. So when I caught the music video for “The Wicker Man” debuting, felt its electrifying chorus surge through me almost so powerful I accidentally shouted along laying on the bedroom floor of my sleeping parents only to hear the VJ announce that it was the lead single from the just-released new album by the band, I had to have it.

One trip to the store later with my allowance in hand and I had my very first Iron Maiden album.

There is a magic to that period of life, where our relationship with music is largely untouched by peers, magazines, critics, or popular sentiment. In truth, I knew next to nothing about Iron Maiden; I knew, at best, a few songs and the general idea that they were considered some of the greatest of the great. So as I, an 11-year-old boy in isolated love with heavy metal in a time where I struggled to get my peers to join along, put that record on for the first time in the black boombox I kept in my bedroom, it was unfettered by the weight of what I thought I was supposed to perceive.

The album swam like Pink Floyd to me, the only real prog band I knew and a favorite of my household, but married it to the weight and heft I had associated with Metallica. Portions of it reminded me of the grandeur, that intense sky-filling billowing of dark clouds rich in storms, that I felt when I first heard Ride the Lightning as an overly-curious child stealing CDs from my brother’s bedroom, or perhaps the similar rich mysticism and boundless sense of adventure I found in Led Zeppelin’s (another favorite of the house) more ponderous epics such as “No Quarter” or “Achilles’ Last Stand.”

I had no strong comparison then in the history of Iron Maiden to wield against Brave New World; even now, claims that it lacks hooks strike me as absurd. I can sing for you every line of every song on this album, can play almost all of it on guitar; in fact it was, along with records by AFI and some faulty and doomed-to-fail stabs at Dream Theater, the record I used to teach myself how to play guitar. For me, Brave New World isn’t merely good or even great; it is ideal.

This is the Iron Maiden of my youth, the one I fell in love with ensconced in the solitary bedrooms of my boundless childlike imagination, stoked into roaring flames by the secret magic of heavy metal.

When I went to college, this was the singular album I used to convert my then-roommates into diehard metalheads, which they remain to this day; screaming along with them in a Maryland field to Iron Maiden performing “The Wicker Man” is one of the most treasured memories of my life. Now 20 years on from when I first heard it, it has lost not one whit of power to me. That there are others who feel the same about this record as me, especially given the nearly peerless ecstasy of Iron Maiden’s mighty back catalog, is a profound and beautiful mystery to me: Brave New World is not just my favorite Iron Maiden record, it is one of my favorite metal albums in general, and one of my personally favorite records of all time, a perfect encapsulation of that first ineffable magic of heavy metal I can recall in my life, a seemingly inexhaustible fire to me.

Happy 20th anniversary, old friend. You mean more to me than you could know.

…

…

Brave New World released May 29th, 2000.

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.

…