A Matter Of Life And Drums: Explaining Iron Maiden Through Rhythm

…

Like any long running British cultural institution, your James Bond’s, your Doctor Who’s and so on, Iron Maiden’s career is generally divided by changes in the face of the franchise. Just as Bond fans argue over the merits of the Sean Connery era vs the Roger Moore era, Iron Maiden fans distinguish the various phases of the band’s career by lead singers, whether that be the scrappy Paul Di’Anno, the soaring dorkiness of Bruce Dickinson, or the ill-fitting gruffness of Blaze Bailey. It’s a reasonable way to categorize a lengthy body of work, especially considering that Iron Maiden’s sound has remained relatively consistent. There will always be harmonized dueling guitar parts, there will always Steve Harris’s sharp percussive bass playing, there will mostly likely be lyrics that read like a book report.

There is another angle to take when breaking down the Iron Maiden catalog. Though they’ve only had two drummers over the course of their recorded career, tracing the way their rhythm section has changed over time reveals a hidden history of the band’s songwriting.

Iron Maiden’s new album, The Book of Souls is on shelves today.

Clive Burr (1980-1982)

…

…

There’s a common misconception that Iron Maiden’s rhythm section uses a lot of triplets. While this isn’t entirely true of their most well known material, and we’ll get to what’s going on in those records in the next section, that description does apply to the band’s first three records with Clive Burr.

There’s a lot about early Iron Maiden that feels incongruous with the way metal is played in 2015, nothing more so than Clive Burr’s swing heavy drumming. Burr was a product of his time. Unlike the ramrod straight playing of the thrash movement that followed in the wake of the NWOBHM, Burr’s drumming carries on the lineage of British rock drummers drawing from the swing and shuffle of American blues and jazz.

Burr’s comfort zone as a drummer was in triple meter, whether that be the bouncy 12/8 of “Running Free” or the loose 6/8 halftime in the breakdown of “Phantom Of The Opera.” Even in spaces where the band is ostensibly playing in straight duple meter, like the double time section near the end of “Hallowed Be Thy Name” Burr’s instincts as a drummer give all of his rhythms a slight lilt that has more in common with the Bo Diddley beat than heavy metal’s standard 16 note pummeling.

…

”Running Free” is uniquely Clive Burr.

…

Conversely, when the band straightened out their 8th notes, Burr’s playing became markedly less creative. Burr’s go-to pattern in situations like this would be to play full measures worth of 16th notes on the hi-hat while keeping the snare on the backbeat, creating what amounts to a souped up disco beat. This pattern is certainly effective, it’s a big part of why “Run To The HIlls” is so invigorating, but it also revealed Burr’s limitations, especially when it came to his fills, which would simply replicate the same stream of 16th notes down the toms with little to no variation.

…

”Another Life” showcases Burr’s ultra-fast hi-hats.

…

By now it’s accepted knowledge that replacing Paul Di’Anno with Bruce Dickinson was a necessary step in Iron Maiden’s evolution from rock club heroes to stadium sized gods. It’s more difficult to determine whether Burr’s departure from the band was as crucial of a change. Burr’s playing, limitations and all, provided character to Iron Maiden’s early period. And unlike Dickinson’s performances of Di’Anno’s songs, Clive Burr’s drum parts still feel appropriate when slotted into their current setlists.

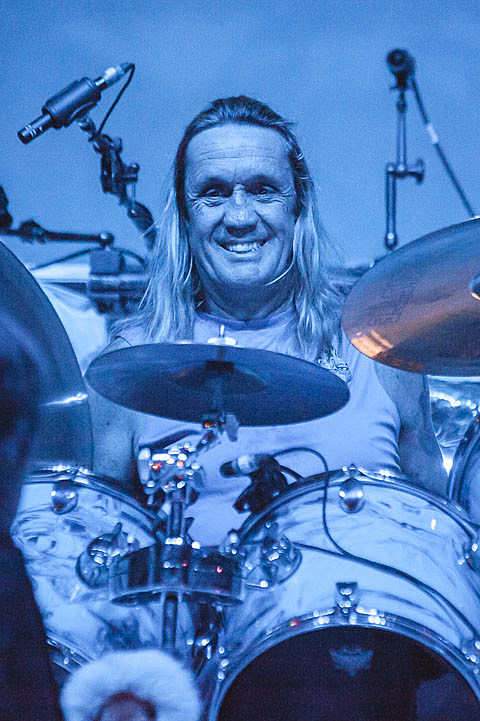

Nicko McBrain (1983-Present)

…

…

Part of the difficulty in imagining what Iron Maiden would have been like if Burr had never left stems from the ease at which his replacement came to embody his role in the band. Nicko McBrain joined the band just as they were hitting their creative peak and his place in the band’s history would likely be secure simply from his involvement in some of their best material. At the risk of sounding hyperbolic, and maybe a bit fanatical, Iron Maiden’s songwriting was so good in the mid to late 80’s that it’s easy to overlook how impressive they were as technical performers at the time.

Nicko McBrain’s excellence can be hard to point out in a metal culture that idolizes displays of near inhuman precision and aggression from its drummers. McBrain’s strengths are rooted in the fundamentals of rock drumming. He locks directly in with Steve Harris’s bass playing, uses high energy fills to set up new sections of songs, and he largely gets the fuck out of the way when it’s time for a guitar solo. What elevates him is the manic enthusiasm he brings to every performance.

…

”Caught Somewhere in Time” – Everything great about 80’s Nicko.

…

Case in point: the combination of McBrain’s boundless energy and his honed in focus on Harris’s bass is the source of one of Iron Maiden’s most distinctive musical building blocks. Though often referred to as a triplet pattern, Iron Maiden’s signature gallop is actually a group of three 16th notes played in rapid succession. This pattern combined with McBrain’s propensity for ending his phrases with a strongly accented anticipated downbeat makes the band seem perpetually in motion. That McBrain was often called on to keep this relentless forward charge going for up to eight minutes at a time, like on “Caught Somewhere In Time,” speaks to both his consistency and his endurance.

Michael Henry McBrain (1989-ish – Present)

…

…

As physically demanding as drumming is, it isn’t a sport. There are no advanced statistics or analytics for me to cite. But at some point in Iron Maiden’s discography, Nicko McBrain’s playing noticeably shifted. While the root elements of his playing have remained the same, the same basic fills and emphasis on anticipated downbeats, over time his drumming has gotten sluggish and heavy handed.

There are two probable factors for this. First, there’s the simple matter of physiology. McBrain wouldn’t be the first drummer to lose a step in his advancing age, although he has no real problem performing the faster tunes from the band’s past. More likely is that the changes in Iron Maiden’s songwriting as a whole has curdled one of McBrain’s strengths. McBrain’s connection to Steve Harris’s bass playing has remained symbiotic throughout their entire career. However, this means that McBrain’s ability to perform exciting drum parts is ultimately dependent on the music that he’s responding to. As Iron Maiden’s music got more ponderous and lengthy, McBrain responding in kind, often abandoning his signature gallop for a simplistic plod on closed hi-hat.

Laying the blame at Steve Harris’s feet is convenient and it does apply to a handful of the band’s shortcomings in the later days of their career. The over reliance on extended and lifeless intros, the ballooning song lengths, and vocal melodies that rarely branch away from the guitar lines all became more prominent on The X Factor after Adrian Smith and Bruce Dickinson had left and Harris took over as the band’s sole creative force. However doing so would imply that McBrain had no agency in determining his drum parts, which is both condescending and inaccurate. After all, it is still up to the drummer to decide how to follow along with bass.

There is one particular beat that Nicko McBrain has come to rely on in the last decade or so. It has a few variations, but it’s defined by dividing up two measures of 4/4 into four groups of three eighth notes followed by two groups of two eighth notes. In each phrase the first note is accented with a snare drum, while the remaining notes are played on the bass drum. This is the pattern.

This 3-3-3-3-2-2 pattern isn’t unique to modern Iron Maiden. Before becoming a prominent part of their sound it showed up in a stripped down form during the intro of “Number Of The Beast” and the bridge of “To Tame A Land.” The first record to feature the beat on multiple songs was Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son where it serves as the verse for the “The Clairvoyant” and appears in an extended form during the solo section of the title track. It wasn’t until the band reunited with Dickinson and Smith in the 2000’s that this beat became a common part of the band’s vocabulary, taking up large swaths of time on A Matter Of Life And Death in particular.

…

A Matter of Life and Death – Where ‘the pattern’ takes hold.

…

In a vacuum there’s nothing wrong with this drum pattern. But it’s increased useage has flattened the pace of Iron Maiden’s music. Used in small doses it helps build tension that’s especially effective when it gives way to a more straightforward backbeat. But once the pattern became the spine of the band’s songwriting, that “tension and release” relationship falls away. The implied triple meter in the 3-3-3-3-2-2 pattern doesn’t have anything to play against in order to actually feel like syncopation. It draws the whole band into a standstill, leading to lifeless vocal melodies and overly long phrasing that ultimately drags the songs out to unreasonable and narcoleptic lengths.

Just as Clive Burr’s bustling shuffle connected the band’s early records to classic rock and Nicko McBrain’s lightning fast gallop signified their dominance in the mid-80’s, the 3-3-3-3-2-2 pattern exemplifies Iron Maiden in their current state. With their legacy firmly in place the band is free to do as they see fit, emulating their classics with no sense of urgency and exploring their most indulgent fantasies of 70’s prog opulence. The bottomless well of energy that seemed to power McBrain in his youth has been stretched out and tampered down, reserved for the moments where the band launches into a fan favorite. There is nothing left to prove, no further heights the band can soar to.

…

Iron Maiden’s new album, The Book of Souls is on shelves today.

…