Aaron Turner Seeks "Love in Shadow" in Philadelphia

…

Don’t believe the rumors: It turns out it’s not always sunny in Philadelphia.

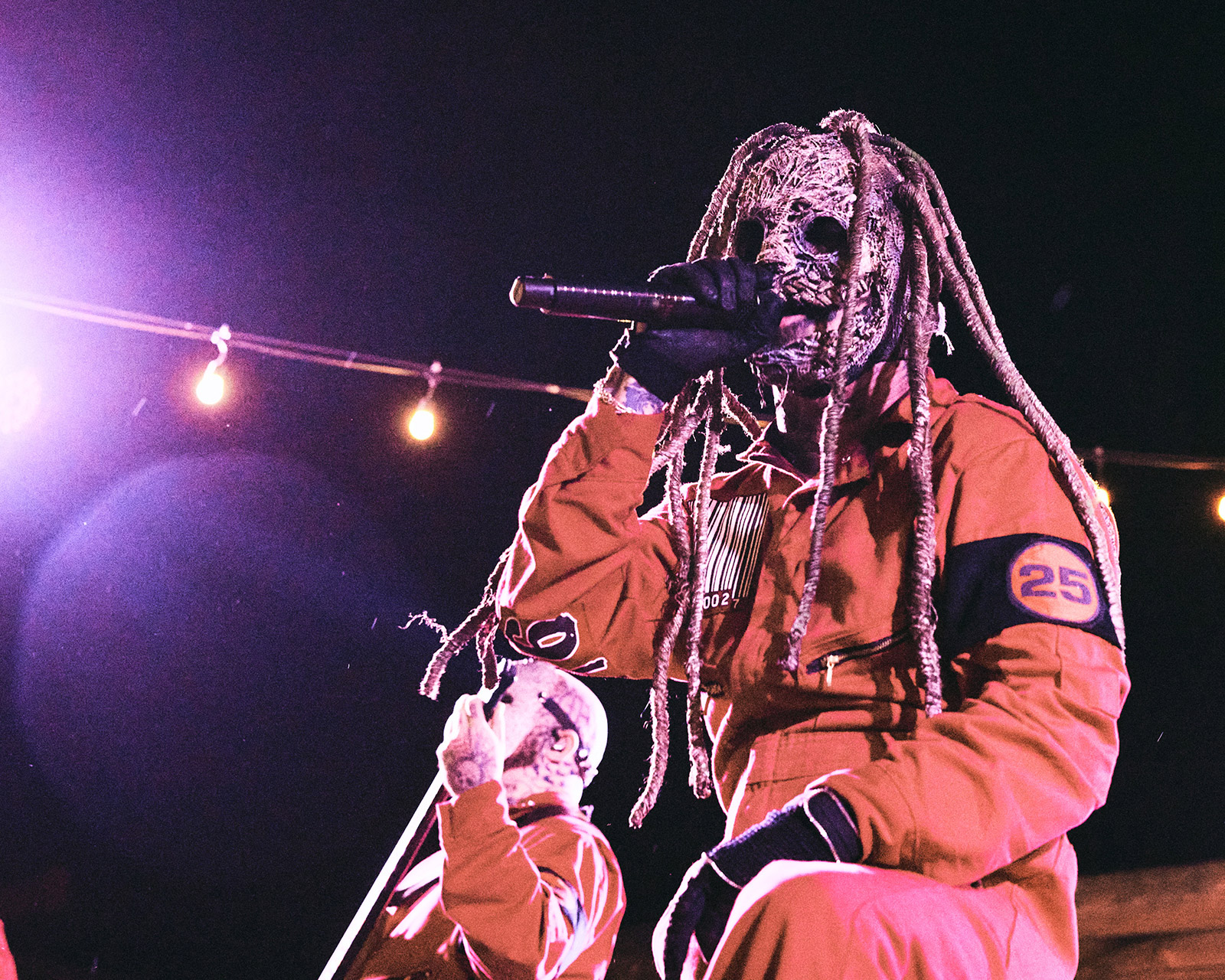

The evening Aaron Turner brought Sumac to the city of brotherly love to debut Love In Shadow, the band’s third full-length, a cold rain fell from a murky grey sky. The overcast weather befitted his career of catharsis — the pioneering post-rock of Isis which put him on the map, the dour sludge-core of Old Man Gloom, the eerie ambiance of Mamiffer, the stable of like-minded bands he released on his label, Hydra Head.

We walked through the steady rain to find the van. The venue for tonight’s performance, PhilaMOCA, is a former showroom for mausoleums that dates back to 1865 repurposed for film screenings, art shows, and concerts. Unorthodox venues often don’t have the expected accruements — there’s not even a suitable dressing room. The only place to speak in quiet is parked a few blocks away from the cracked, ancient, yellowing marble that covers the imposing building.

Although his art is dark and foreboding, Turner was thoughtful and well-spoken, the opposite of what some might expect. Despite being in a cold, damp van and having extra responsibilities at the venue since he was acting as Sumac’s tour manager as well as the guitarist and singer, he spoke with me for nearly an hour. He touched upon the legacy of Isis, the tragedy of his Old Man Gloom bandmate Caleb Scofield dying in a car crash earlier this year, and the two Sumac releases that came out this year..

One of them, American Dollar Bill – Keep Facing Sideways, You’re Too Hideous To Look At Face On, is a collaborative effort with Japanese avant-garde sexagenarian Keiji Haino that came out in February. The other, Love in Shadow, comes out tomorrow. It only has four songs, none less than 12 minutes in length, with album opener “The Task” blowing past a third of an hour. Despite being a man defined by intensity, it may be the most overwrought and sublimely beautiful artistic statement he’s ever been involved with. This is because it personifies his attempt to understand the profundity that is love.

…

…

The name of the album is Love in Shadow. Philosophers have pondered the meaning of love for as long as there have been philosophers. What is love to you?

That’s a difficult opening question. I would definitely say it’s a fundamental source of energy that human life and possibly even animal life revolves around. I think there’s obviously some biological factors involved, but I think that maybe in some way, emotions may be understood on a more scientific level. Some day in the future it won’t be just sort of this ineffable thing that is randomly occurring in our brain. I’ve got to say I don’t really know how to answer this in a big picture kind of way. I think I have to relate it more directly to my own life.

Failing the big picture, how does it fit into what inspired the album?

It fits into the album in that music has been a constant for me in terms of what I love to do with my time and energy in my life. That’s been the case from a very early age. Beyond just being exposed to the music that my parents and my siblings listened to and getting to the point where I started actively being interested in music and picking out what I wanted to hear, I felt deeply engaged by music probably from about age seven or eight onwards. In some way that initial attraction to music and love of music has led to me basing my entire life around it in many ways.

Talking thematically about this record specifically, my desire to live and to embrace life in a very intentional way has to do with how I love being alive, how I love being connected to other people, how important it is to me for our music to address something that feels not only resonant for me and specific to my life, but also something that will hopefully will be resonant for people who come into contact with it.

At the time we were writing this record, I started writing the basic structures of the songs and was thinking about the lyrics and it seemed like the social and political climate was so tense and so rife with hatred and anger that I was compelled to try to find some antidote for myself just so that I didn’t get embroiled in that. But also something that could hopefully be a positive projection from our music that people could pick up on. So that’s where the theme of love came from.

There [were] a lot of different angles that I approached it from when thinking about the lyrics. But the main idea was just that I needed some kind of thing to help re-calibrate myself and ground myself at a time when it seemed like a lot of things in the world around me were just — not falling apart necessarily, but there were a lot of people and a lot of discord and I was compelled to try to find a way to balance that out internally and externally.

It also had to do with becoming a father, which roughly coincided with the making of this record. My son is almost two years old. We finished recording this record about a year ago and I think I had started the writing process just about a year prior to that. So right around the time he was born, maybe just a little bit before that is when I had started working on the music and subsequently the lyrics. That was definitely a very significant event in my life in many ways. Part of it was understanding unconditional love in a way that I never really had before, at least not on a conscious level, and that was a partial springboard for this record as well.

A lot of people revisit their own childhood when they have a child of their own. Did that happen to you and did that make it into the record?

It did, very much so. I think I intuited this and also have read quite a bit about how we develop as people and how our consciousness is formed even prior to being born. Even just in gestation, the things that our parents and our mothers do profoundly affect how we perceive the world, how we relate to the world, how we relate to one another. That’s a thing I’ve thought about a lot because this music in some way is about self-discovery and it’s about trying to figure out who I am, what life means to me, how I fit into the world and also how this act of creation serves to connect me to other people.

That has a lot to do with how I grew up, how I was parented, who my parents are, what their background was. There’s a lot of familial history that goes into what I do both consciously and unconsciously.

I think for sure having a kid heightened my awareness of how profoundly we affect each other as people, but especially as parents and children and as family. I mean, this is where we learn everything about how human relationships work and how to make our way in the world. So that was at the forefront of my mind when working on this record and also just thinking about like what kind of worldview do I want to help provide for my son.

I think I’m ultimately an optimist and I think that having a belief in and a love of humanity is crucial for me. I also think that making music and putting that out into the public forum is an extrapolation of that belief. If I didn’t think that I had something worthwhile to offer and that people wouldn’t in some way benefit from coming into contact with it, and if I didn’t get something back from doing that process, it wouldn’t feel worthwhile to me.

I know from my own experiences that all of the music that’s profoundly affected me has not only added simple joy to my life, but also shaped how I see the world and forge connections for me that have been really life changing. So in some way it’s all interrelated. Even if I weren’t addressing it specifically in this record, which I am, it’s all intertwined anyway. It’s part of who I am. It’s part of how I make music. It’s part of why I make music. It’s just trying to figure out, some of the very fundamental aspects of what it is to be human.

All the projects that you’ve been involved with are personal in nature. Even considering that, would you say that this is the most personal record and the most that you put out there of yourself?

Yes. I feel like I made a conscious effort to be really thorough in my investigation and the themes that I was working with. I didn’t want to just scratch the surface of this stuff that I was trying to write about and I dug into a lot of things which I think go to the core of who I am and how I came to be the person that I am. That said this is also intended to be a record that is hopefully somehow more universal in what it’s addressing.

For instance, one of the things that I was thinking about is in a world like the one we occupy where people are so divided by race and class and country and religion and sexual orientation, there has to be some basic unifying factors that tie us all together. One of the things that I was thinking about was the fact that all people want to feel safe, feel connected and feel loved.

Certainly there’s a lot of metal music where people just espouse a doctrine of hatred, but I think most of the time, except in cases where people maybe are just severely and truly damaged, a lot of that is just posturing. I also think that hate and anger have at their root fear. Underneath fear is the desire to be loved. Essentially, you wouldn’t be fearful of other people or what other people might do to you if you didn’t have the desire to live. And the desire to live is based around, I think, a love of life.

So basically what I’m getting at is, yes, this is all deeply personal stuff and it’s coming from my personal perspective, but it has also with the intention that what I’m writing about are some of the basics of what it means to be human, what it means to love yourself and to love other people. That can be a simple and even clichéd topic, [but it’s] one that can never really be exhausted because it is so much the root of our daily existence as well as our history as a species.

…

…

Many people don’t understand how bone-crunching music with screaming vocals can come from a place that isn’t anger or frustration or strife, very different emotions than what inspired the new album.

Love is not a one dimensional thing. I think it’s often portrayed as such, especially in pop music. There can be the themes of the loss of love or unrequited love that has an element of sadness to it, but often it’s just thought of in this very simplistic sugarcoated a way.

The reality of it is my relationships with the people that I love don’t just involve the good side of who I am and the good side of who those people are. In fact, some of those relationships have very dark aspects to them. There’s anger, there’s resentment. In some instances there has been violence. Those aren’t necessarily a part of love itself, but they are a part of loving relationships.

I don’t know a single person [who] I’ve met who doesn’t have complex, multifaceted relationships with the people they love. Certainly lots of people figure out ways to get along with one another and may even have very peaceful existences with their loved ones but most people I know have strife with the people they love and have complicated relationships with the people who raised them. At times [you] can simultaneously love and hate the same person. In that way I feel like what we do and even a lot of other music that I enjoy and I feel is deeply human, doesn’t just cover one aspect of the emotional spectrum. It covers a more comprehensive vista what people actually are. We are complicated. We are contradictory. We are many things at once.

I feel like this music for me is very reflective of that and it’s kind of reflective of what it actually feels like for me to be a human where sometimes things are turbulent and sometimes things feel like they’re out of control and sometimes I feel like my only means of regaining balance is to tap into anger and even at times empower myself that way. That’s been the way that I’ve gotten myself out of a lot of shitty situations in my life – to finally get angry about my circumstances and use that energy as of as a way to motivate myself to change what I’m doing.

Even beyond that, I was just thinking about this record, if being loved and being cared for and being nurtured as a basic human need, which it seems pretty clear that it is – a lot of scientific studies bear that out. Children who are nurtured thrive; children who are neglected or abused don’t. If that’s a basic human need and it’s not met, that has some pretty serious ramifications on an individual level. That could mean somebody never really finds happiness or contentment or what their path is in life.

On a much larger scale… This is such a clichéd example, but maybe also appropriate: Hitler! I don’t think Hitler came from a loving family. He undoubtedly had some very big needs for love and nurturance that weren’t met and all of that got twisted around and turned in a way that when he was given a position of power had some very, very serious ramifications.

I think that a lot of the things that people go through and experience, including addiction for instance, in any form, have to do with trying to find some way to feel good, to feel comfortable, [and] to feel some kind of joy or contentment. That is a misguided and again, very human way of trying to feel love, I think.

The American Dollar Bill project with Keiji Haino involved you going into the studio unrehearsed, unpremeditated. The new album is also said to rely more on improvisation. How did that jibe with also having these ideas and themes going into the process?

The lyrics and the thematic content had been mapped out. Secondarily I would say all of the music, including the plan to have different sections of the songs be fully or mostly improvised was figured out and even demoed before we did the session with Keiji Haino.

I think what happened in that session that was important and fed into the making of this record was a gain in confidence amongst the three of us as a trio of improvisers. We had done that to some extent with other songs, recordings, and live performances, but never to this deeply immersive extent that we did with Keiji Haino.

Leading up to the meeting with him before we went to Japan last year, we spent some time rehearsing together where we would play our songs, but we also would just start without any preconception or discussion about what was going to happen. That was sort of like our boot camp for the Haino sessions. That was a really good first step. Then the sessions and the subsequent show we did with him there was furthering that learning process for us.

So while I think that the overall shape of the record would have been essentially the same if we hadn’t done that, I think the level of confidence that we had because of those experiences going into the recording sessions definitely helped us a lot.

The album is sprawling, four songs that last an hour and change. You’re no stranger to having lengthy songs but not to this extent. Did you expect something like that to happen or was it more organic?

I think I’ve been intentionally trying to get there for some time. Even with Isis, there were times where I really wanted things to stretch out more than they did and just the collective involved made that difficult. I think we all had different ideas about what worked in terms of song structures and song length, and we had to come to some kind of compromise in terms of what worked for everybody.

Within this group there have really been no limitations set. I think it’s just an ongoing process of learning how to write and make music together in a way that feels like it’s progressive and Intuitive and also purposeful. I don’t want to make long songs just for the sake of doing it. It feels more interesting to me to expand song length when there’s something about the extended duration that feels good. With these songs, just the way that they were written and just writing the way that we do is part of the reason why they ended up being as expensive as they are.

The first track, “The Task,” we had an initial stopping point for that song and after listening to the rough mixes, I just realized that the song still felt unfinished to me. There was something else that needed to happen. So after spending some time thinking about what that was going to be, the song grew even further in length.

The thing that’s interesting to me is when we play these songs now – the set we’re doing on this tour, we’re only playing four songs, but somehow the set feels shorter to me even though this is probably the longest set we’ve done. It’s because of something about the flow of these songs and also something about not stopping and starting songs in shorter intervals. When you just go and go and go, I feel like the momentum can carry you away. It at least offers the possibility of breaking through the barrier of your rational mind and allowing you to just exist more within the song and within the moment that it’s being played. That kind of dissolves the notion of time itself and I think that’s a big part of the reason why long-form song structures are appealing to me is. It can distort your sense of time, it can break it down, it can offer you a different kind of experience than what you get if you’ve got the typical three to five minute song and a fairly predictable course that the song is going to take.

…

…

The album closer “Ecstasy of Unbecoming” might be the most adventurous thing you’ve ever done. It’s pieced together like classical music with all of these different segments. I can’t tell if there is any extra-instrumentation but it certainly feels like it at times and it has this amazing triumphant conclusion that finishes the album in a perfect way.

I think though we’re using a basic rock format of bass, drums, guitars, and vocals, we’re definitely trying to push the boundaries of what our instruments in do in that format and trying to coax a lot of sounds out of our instruments – I guess it’s an exploration of extended technique essentially – and using a limited number of tools and having a limited number of band members and trying to create the biggest sound possible. [Having] the widest palette of sounds from that very basic setup is really intriguing to me.

That’s also was part of the mission statement for this band: What can we do with three people and this kind of limited instrumentation? How far can we stretch it? And how broad can this scope be between purely improvised stuff, including things that are not even rhythmic or vocal, all the way to these very precisely composed moments that are pretty complicated. That’s interesting to me, to traverse between those those pretty different realms of making music.

You closed Hydra Head Records to new projects pretty unexpectedly in 2012 but almost as unexpectedly ramped back up to put out the Oxbow record last year. Will there be more new releases on the label?

We’ve got one more. The drummer of Sumac, Nick [Yacyshyn] has another band called Erosion and we’re releasing his band’s album in October. That’s technically our third newer release since I stopped doing new releases some years ago. We did the Oxbow record, we did the most recent Endon album and we’re doing this Erosion album.

All those [projects] involve people in music that [have] deep personal significance for me and I think that that is the incentive to become involved in projects like that. If I liked the people involved, if I believe in what they’re doing, and if I feel like we’ve got some kind of creative kinship, that’s a lot of incentive for me to get involved and to put my energy behind it.

That said, I definitely don’t foresee a time that the label ever becomes as active as I once was. I don’t want to be constrained by it in that way where I have to be putting out x-number of records on a monthly basis in order for the business to maintain some kind of level of public profile or financial stability. I want it to be what it was in the beginning, which is just something that I was excited about being involved with: Putting out records that I was excited about and doing it on a very manageable level. Running a multi-person business is not something I think I’m necessarily cut out for and certainly at this time in my life, I’m a lot more interested in spending time with my family and facilitating my own creative work than I am spending the majority of my waking hours working on other people’s records.

So Hydra Head began out as a creative outlet that kind of became a job and that sort of became a drag. Does it ever kind of worry you that creating music might become a job and become a drag?

Well that’s definitely what happened with Isis. It was never supposed to become this thing that allowed all of us to quit our jobs. As grateful as I was and presumably the rest of us were that we could just stop having day jobs and spend all our time doing the band, it also is ultimately part of what killed it.

I’m very cognizant now about what kinds of choices I make and how I choose to operate things in the bands that I’m in. I think the two main factors I really try to keep in mind as the grounding forces that let me know where I’m at or what I need to be doing, one is if I’m getting along with the people that I’m doing it with. I never again want to be in a situation where I feel like I’m stuck with people that I don’t want to be around because we have this thing together that we’re obligated somehow to keep doing.

The second factor is, am I still finding joy in the music? Because that became a thing, too, where making music started to feel like a chore and I never ever wanted that to happen. That was another wake up call for me. I was like, okay, I’m not enjoying this thing anymore. That was like the whole reason I started doing this to begin with.

So as long as I’m getting along with the people that I’m playing with and I’m finding joy in the process of making the music, whatever else happens or doesn’t happen around that is of lesser consequence. So if we exist on a level where we can’t really tour because it’s not financially practical based upon small audience size, that’s just the way it’s going to be. If we get out and tour and are able to bring home money, that’s not a bad thing. I’m happy if I can provide for my life through making music. I just don’t want that to be the reason that I’m doing it.

…

…

You mentioned Isis couple of times. You’ll be having an Isis reunion next month to honor Caleb Scofield’s memory and raise money for his family. Reunions are supposed to be celebratory — and maybe this will be, but in a different way. It seems like it’s bound to be an emotional evening.

It’s tough. The toughest thing is that we’ve all lost a really, really good friend and I think coupled with that is knowing that his family lost him as well and on a much more profound level than we have. For me that has always been the critical factor in this thing, thinking about Caleb, thinking about memorializing his life and also doing something to help his family. So that’s the main thing. That’s why this is happening. That’s why we’re doing this. Caleb was very important to all the people in Isis and obviously the people in Old Man Gloom and Cave In even more so, but we all just wanted to be able to do something for him and for his family. In some way this feels like [it’s] not the best circumstances, but the best reason to get together to play music again in this particular formation.

Aside from the various obvious factor of why we’re doing it, there’s also our collective history which has its own set of complications and emotional ramifications. I don’t really know – I mean, I’ve thought about it a lot of course — but I don’t really know what it’s going to be like. I’m trying not to have expectations about it being one way or another because that’s just a way of trying to control something that’s ultimately way beyond my ability to control.

I definitely don’t foresee this being the beginning of us playing together again. In fact, that was one of the conditions for us going into this. This isn’t the beginning of a reunion cycle; this is for this event and this event only.

But at the same time this band was a very big part of all of our lives and it connected us to a lot of things and opened up a lot of doors to paths that we’re all still walking on. There are no other people in the world [who] I will ever have those kinds of formative experiences with. So it’s good to be able to come together for this reason and do this. If nothing else, I feel good about doing that for Caleb and for his family.

I’m going to go out on a limb and assume that you’ve actually heard the term “NeurIsis.”

Yeah, that was thrown around a lot in the early days.

My impression was that the term came about because both you and Neurosis helped create this important subgenre of metal. Do you ever sit back and think about that? Especially when you’re listening to the tenth band that day that sounds like they do because of your inspiration?

It’s funny hearing that term “NeurIsis.” Early on that was like a derisive term applied to us as just being Neurosis clones. That was where we first heard it. There’s no doubt that they were definitely a massive influence for us musically and also kind of ethically; they operated in a way that informed a lot of how we chose to be a band.

But in terms of the level of influence that we’ve had, I’m grateful. In some way I hoped early on that the music I made would be meaningful and inspirational to people. As I said earlier in the interview, music changed my life in a very real way. The music that has meant the most to me has been a huge part of my joy of living. To think that in some way what I’ve been a part of has given that to other people is something that I’m definitely happy about. I’m glad that people have found something in our music that makes life worthwhile in some way or makes them want to play an instrument or makes them want to start a band or whatever it may be. That’s something I definitely and truly appreciate.

I also don’t spend a lot of time reflecting on it. If anything, I spend a lot more time reflecting on what I’m doing currently, what about it is satisfying to me, what I would like to do differently and what am I going to do going forward.

…

Love In Shadow will be released on September 21st. It can be purchased directly from Thrill Jockey Records. Sumac can be found on Twitter and Facebook.

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon.

…