Yob's "Atma" Returns, Its Surfaces Gleaming (Interview with Mike Scheidt)

Listening to Yob‘s discography is like exploring an ancient landscape. There are ruins, pieces that hint at some illustrious, bygone time. There are necropolises, valleys half-drowned in sand that are full of sealed-off treasures. There are also monuments, rising with timeless triumph. Atma is firmly in the latter camp. It is furious, yet deliberate; it has moments of solemnity and moments of chariot battle.

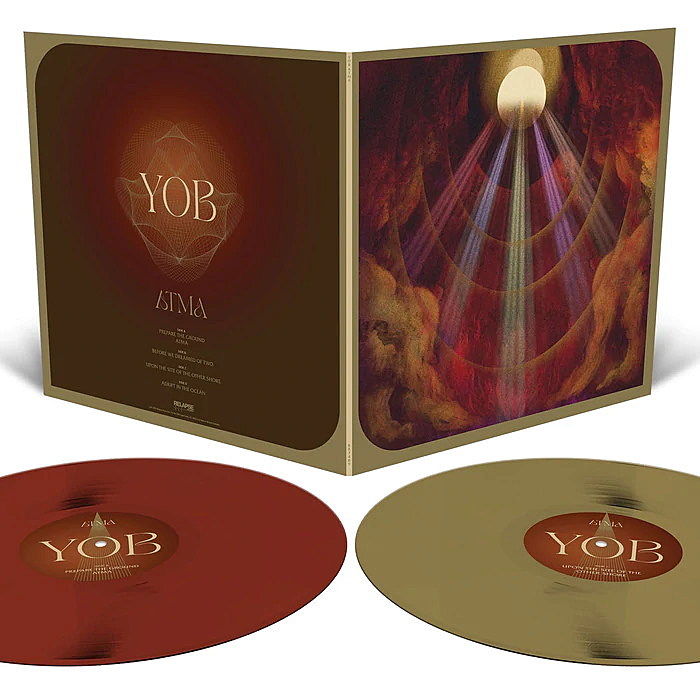

However, until this year, one could argue Atma lacked a certain polish. Like a ziggurat eroded by nature, its surfaces were partly obscured. Drum passages were dulled, their gilding worn away. Gusts of panning blew listeners off course. That’s changed with the album’s remix and remaster, out April 8th on vinyl via Relapse Records. This careful revisitation of Yob’s 2011’s masterpiece is more conservation than restoration—rather than re-record or repaint the full-length using contemporary colors, longtime Yob collaborator Billy Barnett worked from Atma‘s original recording tracks and carefully realized the band’s initial vision as Yob had come to feel it should sound a decade on.

A listen to the album’s titanic closer, “Adrift in the Ocean,” is indicative of the whole record’s treatment. Drums resonate; cymbals clatter. The guitar tone is the original, but with a keener edge, and the album’s low end fills the room. Songs moves close and then rear back, building tension. Careful listens even reveal the occasional pick sound or the whisper of high-hats touching. It’s a very live experience of Atma. The record’s new packaging, completely distinct from the original, reflects the luminous new album within.

Yob songwriter, vocalist, and guitarist Mike Scheidt is a man who considers his words carefully. The band’s approach to their music reflects some of this circumspection: “We move slow,” Scheidt says. However, Scheidt and bandmates Travis Foster (drums) and Aaron Riseberg (bass) aren’t exclusively informed by doom—in fact, Atma has firm roots in punk. “We’ve always been very heavily into Poison Idea and Minor Threat,” Scheidt says. He cites Corrosion of Conformity and Black Flag as other influences as well as Neurosis, High on Fire, Corrupted, Swans, “and other weirdo stuff out there. But,” he adds, “also a lot of ’70s pop—Joni Mitchell is a big one for me, especially the way she uses space in some of her piano and vocal compositions.”

It’s this use of space that really defines Atma 2.0 (or, perhaps, 1.1). “Prepare the Ground” has a celestial hugeness to it without irritating, bricked-out loudness. “Upon the Sight of the Other Shore” feels more dolorous and punishing than ever. Like the band’s other remasters, it is what all revisited albums should be—a better version of the original for those who care and, more importantly, for the band.

Scheidt feels “optimistic” as the band embarks on their first tour since 2019. Curious about the process of sculpting this reissue and the band’s perspective on this new version of Atma in the context of their other work, I reached out to him for an interview. We chatted about Atma, the evolution of Yob’s sound, the pandemic, and more via Zoom. The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

…

…

Atma turns 11 this year. What prompted this remaster and reissue with Relapse?

When we first recorded Atma, the idea was we wanted more of, like, a punk recording, in the sense that we wanted it to be rough and have this kind of by-the-seat-of-your-pants energy. We were referencing the early Sleep recordings, the kind of recordings that were happening in the stonerrock.com days. We got that, and then, over time, I think it was [drummer] Travis and [bassist] Aaron that were both feeling kind of dissatisfied with the drum sounds, dissatisfied with some of the panning. They first mentioned back then [they thought it] would be really cool to jump in and remix it. At the time, I was really hesitant because it was a record that had already been really well received and was loved as it was. I know that when some bands jump back into their old records and do a really hot remaster, it becomes kind of an ear-sore to me, and then you go back and you can’t get the original master anywhere unless you go into Discogs or something like that. So I felt nervous for fans of that record.

When the pandemic came around, the idea came up again. For my part, the idea had sat with me for a couple of years at that point, and there was a good case to be made for giving it a go. We’re not touring, we’re not far enough along with our new music to take that on, and it felt like a nothing-to-lose, let’s-go-for-it situation. So, Jeff Olson comes and brings us a hard drive of all the original tracks to Gung Ho Studio with Billy Barnett, and we have a pretty lengthy discussion about what our goals were, which were, firstly, do no harm. The things that are really good about the record, we’ll need to keep; the things that need to be improved, we’ll discuss on a case-by-case basis. And also, [we’ll trust] Billy Barnett. He’s been working with us since 2004, so he knows us. We have a kind of template with him we’ve been building together over the years.

The remastered production brings a certain clarity to the record. What would you say this remix and remaster does that the original version doesn’t?

First of all, we didn’t “fix” anything. We didn’t touch anything—we didn’t touch any performance or sparkle any kind of inconsistency up; we just kind of left it as it was. The original mix had kind of a weird panning to it, where someone compared it to Pet Sounds, [like it had] kind of a mono thing. I think that’s pretty accurate. We panned it volume-wide, panned it hard from right to left. We didn’t touch the guitar tone too much, though; we still kept that raggedy edge to the guitars. The drums are probably one of the more drastic things we did. We just got the drums sounding good. We let Billy run with it for a couple of days before we heard anything. We weren’t very far into the process before I started feeling like an idiot [for second-guessing the reissue]. Aaron and Travis had wanted this for a long time, and in the process of doing it, I became a believer. By the time we got to the end of it, all of a sudden we had this old record that [had become] a new record. Sonically, it just magically sits with The Illusion of Motion, The Unreal Never Lived, and Clearing the Path to Ascend—it just fits into our lineage automatically now sonically as well as [in] songwriting. The songs have always worked well. Those songs are always requested, whether it be “Prepare the Ground,” “Atma” or “Adrift in the Ocean.” Now, to have the recording, mix, and production fit the quality of the songs, yet when I sit with it side by side with the original mix it still carries more of the flavor of the old mix than it doesn’t—we’re thrilled.

You also re-released The Great Cessation about five years back, and there was a Catharsis reissue in 2013. Can we expect to see other remixes or re-releases, or is this more of a case-by-case thing?

I think we will. It’s a matter of time and resources, really. If you look at our history, certainly there was a period of time where we put out a lot of records, like an every-couple-years kind of thing. Now, we’re starting to move slower. As far as our growth, it has been very slow. We do things slow. We take time to listen to ourselves and determine what we want to do next. We’re not out there relentlessly touring. It’s the same with releases these days—when we put something out, whether it’s a release, reissue or whatever, we want to let it sit out there for a minute before we do something else. There’s no big intention around it or strategy, per se. In fact, our strategies generally don’t go beyond the next tour or the next record. We don’t think too far ahead. We just want to make sure what we’re doing is quality.

You were talking about the kind of punk nature of Atma. It’s among the faster records in your discography. What went into the record at the time you wrote it as far as influences, songwriting, that kind of thing?

At any given moment, whenever we start writing, there’s this drive to write. For me, it always starts the same way, where I have this specific idea of what I think I’m going to write, and then there’s this struggle between what I am writing and what I want to write, and then I eventually get out of my own way and let what happens happen. Sometimes, that means songs I intended to become fast, become slow. I’ll be playing it fast, and it doesn’t work and doesn’t work and doesn’t work, and then I’ll play it three times slower and go, “ah, there it is.” Or sometimes I play slower parts and think it’s missing some juice, so I’ll speed it up three times. As far as what was specifically happening at that time, we were pretty fresh off of [The Great Cessation] and… there was just this sense of overall momentum out of nowhere. Before we did The Great Cessation, I mean, we’d had a break, [and] we didn’t really know we’d grown in our absence. It was kind of a surprise, the response, and that there all of a sudden seemed to be more widespread audience. We’d just done Roadburn—and so there were a lot of things that were surprising, exciting, energizing, and it all just went directly into Atma.

Notably, your reissues all have new cover art. The new art on Atma is much brighter. Tell me a bit about the process of choosing how your albums look.

Hmm. It’s probably not very interesting—I think when we’re talking to artists, it’s probably very frustrating to them. We’re very vague. We say “we want things to feel spiritual without looking spiritual.” We don’t want there to be overt iconography or overt symbolism, especially these days. We want it to feel esoteric but not malevolent. Believe me, I’m a huge black metal and death metal fanatic, but that’s not our deal. So, from there, it’s a matter of starting to build the ideas, and generally it’s a matter of subtraction rather than addition. We just go through different color schemes and sets, and it’s almost nonverbal the way it comes together. The artist who did [the new cover for Atma, Orion Landau, also did the reissue of The Great Cessation‘s album art as well as Clearing the Path to Ascend and Our Raw Heart. He was Relapse’s main art and layout guy for I wanna say three decades, so he has a lot of experience. He really just jumps into the deep end with us, and we have a kinship with him on multiple levels. We take turns kind of surprising each other on where we want to take it next. To me, it’s astonishing where we start and where we end up because we don’t send him three paragraphs or have him respond to the lyrics. He usually has the music, but it’s really kind of a mystery to me how it ends up.

How has your older work changed or aged for you? Do you see it through a different lens now?

Some of it hasn’t aged very well for me. Certainly, I’d say our demo and some of the stuff off our first two records, I can look at that with a correct lens in that it was the best that we had in the beginning. We were sincere and full of fire and throwing out what we had in us, but there are songs from that era that I have zero desire to play. I know it would make people happy, but it feels like such a drastically different band. It’d be hard for me to play it and not be cringing the whole time. For anything that really has stuck with us over the years, there are moments where I can look at it and be like, “this is the beginning of the realness.” Over years of countless rehearsals, recording, hundreds of shows, that as we get better, our back catalog gets better, too, with us. The version of “Ball of Molten Lead” we play today—we’re a better band playing it than when we wrote it. There are songs that have grown with us, but it’s always a brand new discipline. Every night, even though you know the song inside and out, you’re creating it again, from silence to the first note to the last note. I’m really glad we have so many songs in our back catalog we can continue to do that with.

People ask me all the time if we have new music, or when are you gonna put out new music, and look, not to sound like a dick, but I think this is true of a lot of musicians—you can write riffs all day long, but riffs aren’t songs, and even a songs isn’t necessarily a vibe. There’s a muse quality to music, to the thing that glues it together, to the spirit of it. That’s the thing that carries from decade to decade, that expression of that real thing. It’s like trying to get a bird to land on your hand. You can’t make it happen—you have to cultivate the spirit for something magical like that to happen. That gets harder as time goes on. Having been around for a while, certainly we have increasing demands on ourselves of how well we record and what the music is to us. Sometimes, I hear things that I don’t know how to play yet—there’s a process of growing into a thing I don’t know how to do yet but can hear in my head. That could be vocally, musically, or something that’s hard to put my finger on. I know I need to start cultivating whatever disciplines that my intuition leads me toward. So when people ask for music, that’s what they’re asking for. They’re asking for that inspired, real thing that was medicine for us at home first, and we’re the control group. If it works on us, we can take that and it’ll work on stage and maybe work for somebody else. As far as outlook, that’s where it’s at now. Over the years, too, as far as the lyrics and intent of how we exist in the world as a band, that’s slowly becoming more refined as well, and yet we don’t really like to plainly speak those things because it’s hard to describe. It’s figuring out new ways to put that out there and on one hand have it be the thing we want to express and on the other having it be open to interpretation and subjective.

Yob’s lineup has stayed stable by metal standards. The three of you have been playing together since the mid-2000s? What’s your creative dynamic as a band, and what keeps you on the same page?

To begin with, I write most of the music and all of the lyrics. What I mean by “writing the music” [is] the riffs and a lot of the structures of how things glue together, but there’s no part of that process that doesn’t get chosen by the band. So, I could come to practice with 20 ideas for songs. The band chooses which ones become the [songs]. Part of it is how we feel while we’re playing it. Let’s say there is something we really all resonate with, then it’s a matter of climbing into it together to figure out how the rhythms fit together. Aaron and I figure out basslines and where my melodies are sitting and basslines complement that. I’m not a great drummer, but I am a drummer, and I write for drums. To me, drums decide how a rhythm comes across, how a tempo for a rhythm comes across. When I’m writing, I have a certain idea about how things are going to flow. Travis and I have lots of conversations about drum beats, and sometimes trade ideas back and forth; we’ll demo ideas with him playing, with me playing. If anything, my ideas are like springboards to be like “this is the rhythm, this is what I’m thinking,” and then Travis takes that idea either completely rewrites it or makes it, I dunno, 50 times better. Nobody writes each other’s parts. We don’t write things that we all don’t feel great about. For every one thing that becomes a song, there are at least ten ideas that remain on the back burner. Either they eventually become a song, or they become pieces, like LEGOs, for other songs.

You’ve got a pretty big tour starting this month. Are your setlists going to be

Atma-heavy? What’s the experience of launching into a tour after two years of the pandemic?

There’s going to be a fair amount of Atma, but there’s also going to be Clearing the Path to Ascend, Our Raw Heart, The Unreal Never Lived and The Great Cessation. There’s a mix of things we’re playing with. The shows we’ve done so far, I can only speak to that. To actually go out and travel is going to be another thing… It’s strange and wonderful, and the strangeness is partly the atrophied muscles of not having been in crowds for a while, not having been on stage playing music, things like setting up your gear. It’s like if you’ve been in your apartment too long and go to a bar and you kind of feel like you’ve forgotten how to socialize. Just multiply that by a couple years, but everybody’s in the same boat. It’s a lot of people looking at each other like we just almost got into a really bad car wreck, and the look you give your friend, like, “dude.” That’s kind of the feeling in the room a little. Generally when you go to shows, people have different expectations from the band, and the band has expectations about what they hope for from the crowd. Now, it feels like everybody is doing the heavy lifting together and is just happy to be there, and that’s an interesting vibe… It seems like this is the time to do it. I feel pretty optimistic all in all. Optimism has a much lower cost on my nervous system than being fearful. I’m being cautious but putting fear on the back burner.

Has changing your vocal approach changed how the songs on Atma sound or how you perform? I know you did some adjusting after your stay in the hospital.

The thing about Our Raw Heart, between the nature of the abdominal surgery and having to stretch all those things out again, I was able to lean into my vocals in a different way because I hadn’t been singing continuously. Some of the lessons I got from my teacher, Wolf Carr. Some things I didn’t understand before I was building myself back, I started to intuitively understand, like how to loosen my tongue—to get my tongue out of the way, I had to drop my jaw—how to sing more from my forehead than my throat, how to send death roars and screams past my vocal folds to my false vocal folds. That matters if you’re doing 26 shows. Because I was still recovering, there were things I had to do for my health. I couldn’t just hang out in the crowd. I had to really spend a lot of time downing water like crazy because I’d lost a chunk of my large intestine and that’s where a lot of your rehydration happens. It forced me into habits that ended up making me better. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve been singing this way for quite a long time, and there are things harder to do than they used to be. I think that’s true for anyone. I’ve watched later performances of my favorite singers like Halford, or the later years of Dio, and they lost some range, but they certainly didn’t lose their fire and gusto. I try to keep that in mind and follow good vocal habits, warm-ups, warm-downs. As long as I do that, it seems like the longer I’m singing these songs, the more my voice is growing and changing. Mostly for the better, as far as I can tell (laughs).

…

Atma reissues April 8th on Relapse Records. You can pick up an oxblood/metallic vinyl variant here.