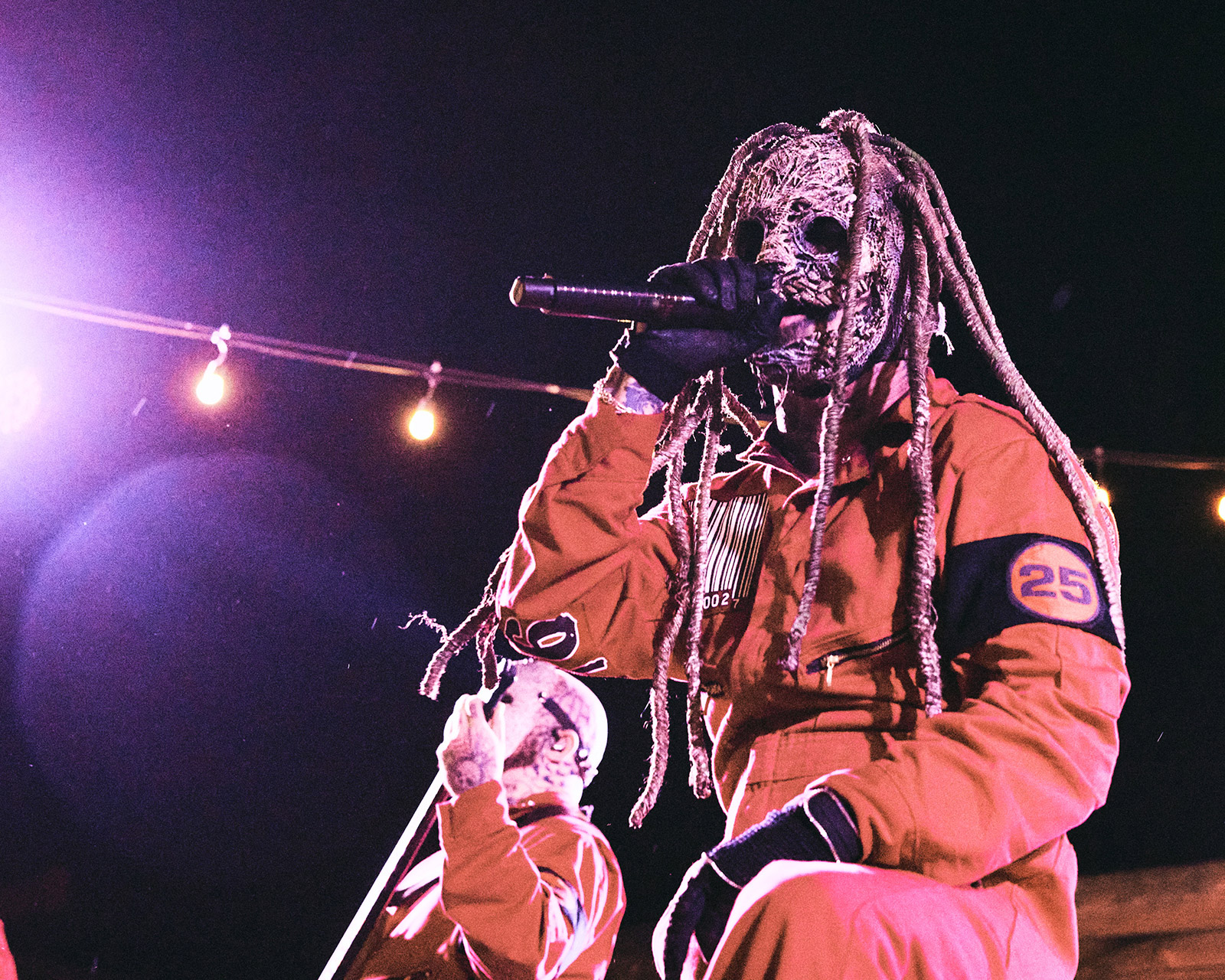

Woe Have Seen The End (Interview)

For all its surface-level aggression and posturing, black metal sure does spend a lot of time hiding. Be it behind theatrics, costumes, or sheer musical impenetrability, black metal has a habit of obscuring itself, calling to mind the beard-weary opening passages of Roald Dahl’s The Twits–what exactly is hiding in there?

Woe have long bucked this cliche, keeping their substance in plain sight and rooted in reality: see it in the polluting black smoke and subject matter of 2017’s Hope Attrition, and in the scorched earth and righteous anger of Legacies of Frailty, released this Friday, on which multi-instrumentalist and Woe mastermind Chris Grigg rails at the world in disbelief at mankind’s inability to learn from its own mistakes.

We sat with Chris to discuss the album’s narrative, society’s stalling progress, and which John Woo movie best describes Woe's creative process.

…

…

Legacies of Frailty is the first album you've created in relative isolation in a long time, was that a circumstantial or creative decision?

It kind of changed over time. It started as circumstantial. I've written all of the albums by myself, demoing them at home, then sharing demos with the band, and then expecting or encouraging or welcoming some amount of modifications in the room, after I say, “Here's the demo; here's what I think.” And then sometimes things change, and sometimes they don't.

But especially coming off of Hope Attrition and A Violent Dread, we had a really good dialogue within the band, a really good back-and-forth, and creative energy in the room. So going into this one, I really had the same expectation that we're going to get in the room; we're going to start learning the songs, and whatever happens, happens. And then, as time went on, and the pandemic roared on, people's lives and schedules just changed the boundaries of things and changed the availability of people, so that didn't happen.

What did happen was, I wound up spending more time and going in deeper and deeper and deeper with the writing, and then one day, I woke up and realized that there was this mountain of very dense material to be climbed, that I knew extremely well, and most of the other guys didn't. So we had a conversation about it, and just decided that, given the complexity of the material, the amount of it and just the schedule that we wanted to hit, pending everybody's availability, we thought it would be best for me to play the majority of the material.

So at that point, I was expecting to do everything except for drums, Lev and I spent a lot of time working on the drums and he was the outlier because he's still local. So Lev and I worked on it and ultimately came to the same conclusion, which was that my relationship with the music was very different to what anybody else would have just by virtue of being a maniac who obsesses over details. And so we made the decision that the version of the album that we wanted to release was the one where I was doing everything. We agreed that I should just go for it, so that's how it was.

Lev does feature on the record right? On specific songs or sections.

Lev is the only other person who actually plays on it. But of course with Grzesiek as producer, his fingerprints are all over it. I've never worked with a big name producer, but my understanding of how they operate, at least from when I've been in the producer's chair before: guiding the performances and pointing out details and encouraging you to accentuate this or that and having a hand in the songwriting, talking about the arrangements and things, Grzesiek does all that.

He was there when I recorded drums, and he was telling me no, that take was bad, do it again. Matt isn't on it but I wrote a lot of it with Matt in mind, I wrote a lot of it thinking: what are the riffs that we all feel the most intensely when we're playing? What are the preferences of the band, and how do I write with these performers in mind? I want to think that they're all, in their own way part of it.

It makes sense to put yourself in that mindset if you're thinking forward, especially for touring.

Absolutely, I write a lot of drum parts with Lev in mind, and you can hear on this album for sure, but especially on the last one, there are parts that Lev plays where it's almost like, have you seen the movie Face/Off? (laughs) So, you know, Nic Cage and John Travolta have these amazing scenes where it's Cage doing his impression of Travolta doing an impression of him. There are spots, especially on Hope Attrition, where I wrote a part with Lev in mind, and then Lev is interpreting my interpretation of him. On the new one, I wrote some drums with Lev in mind, and then I wound up playing it, so it's me playing my version of Lev's drum parts.

I remember reading an interview that Ihsahn from Emperor did ten years ago, where he was talking about the differences between writing for emperor and writing solo material, and he talked about how when writes for Emperor he is the same person, and it is his voice that can be heard everywhere, but he's still in this other mind, this other idea.

I really liked the John Woo analogy and fully expect you to release some doves at the start of any upcoming shows. So thematically, the album refers to these themes of aggrandisement and the arrogance of human legacy. Why was this at the forefront of your mind at the time you were writing?

(Laughs) What could possibly be going on? I want to try to answer this carefully. Not because I want to be evasive—I don't. But I don't want to send the wrong message. So obviously it's written against the backdrop of the past few years politically and socially. So of course, when I'm writing, I'm seeing, seeing a lot of the world struggling with, and struggling to overcome problems and conflicts that for me personally, from my limited perspective or privileged position, I thought were very much settled. We woke up one day, and suddenly people are debating whether vaccines will kill you, and we've got Nazis marching in the streets and trying to take our government. And I know there are plenty of activists who would say, nah dude, this never went away. And of course, I grew up in punk; Woe has been covering "Fuck Nazi Sympathy" since the beginning, it's still a problem, especially in underground music. But in underground music, it's not mainstream.

Suddenly conspiracy theories are mainstream, WEIRD conspiracy theories are mainstream. And we thought we were smart, we thought we were enlightened; we really thought these things were gone. This was dead. We defeated the Nazis in the 40s; what is going on? And these are very self-inflicted wounds, you know; these are unnecessary, This doesn't have to be happening.

And it's striking to me, because it feels like the past kind of roaring back, maybe things that we should have examined more closely. Maybe we should have looked at these things and said hey, this stuff is still festering; we need to really have serious conversations about these things and figure out what to do about it. But instead we thought, ahh, these kooks, these extremists, they're not a threat. And then suddenly you've got Charlottesville, you've got hate crimes on the rise everywhere. It weighs really heavily on me, and thinking about that, in the bigger picture of inequality, the rise of the super rich, the housing crisis, the opioid crisis, the collapse of the environment. We see the social fabric breaking down; we see economic stability in question; we see war on the rise, we see the planet collapsing, all kinds of coming together and it had me thinking in very apocalyptic, very metal terms.

You can string it together narratively, and talk about this thing that comes back, and there are people who embrace it, and then we start fighting each other, and we're unable to change the path that we're on. So the album flows narratively, just like that, from the awakening of the thing, to looking to the future, what will there be to inherit is the question that's asked at the end.

I said in the beginning, I wanted to answer this carefully, and instead, I went deep into the meaning! The reason I said I'm gonna answer carefully is because that was all my perspective, but when you look at the lyrics, you'll notice that few of those things are called out very explicitly. I don't want to write an album that only makes sense in 2023. I don't want to write an album that is so hyper-specific that it has no relevance beyond that. So it's written very deliberately, in a way where I want the listener or the reader to be able to map it to their own concerns and their own fears.

My understanding is that if you poll Americans to ask, “Is society on the right track?” we all agree that it's not. And depending on where you're sitting in the room, you're gonna get different answers about why. I do think that there's something special about art that allows the person perceiving it to apply their own world to it and to map it to their own experiences and their own perspective. So while, of course, it was written from my perspective, I do want it to be an opportunity for the listener to find their own interpretations and their own meaning.

It has been strange in our adult lives to see the social and political process start to stall and stutter, when we've only experienced them as a constant.

Crazy, right? The rise of authoritarianism, worldwide? I'm right there with you, I assumed that we were making progress, that progress is a forward path. And we're seeing that it's not, it's not a straight line. That is really what the album is about. That plus, you know, we're all gonna die, none of this will matter when the planet is uninhabitable.

As I hear you talk about it, it sounds like you're coming from a place of sadness and of concern, but the album is an angry sounding album. It sounds very direct and very urgent—Does that tie in with subject matter and how you feel about it?

Absolutely, and I'm very, very happy to hear you say that. Yes, an urgency. If I was to create a little, like, a word cloud of the feelings on the album, it would be one of the big ones. Anger would be one of the big ones. It does feel extremely urgent. Because for all of us living through it, there is an urgency to it, right? These are not some vague speculative fiction predictions. These are not theories about the way things could go. This is right now; this is Russia dropping bombs on hospitals; this is this is a hurricane hitting Southern California; this is real; it's fucking insane, man.

We see a lot of metal that's pure speculation or fiction, it's orcs and dragons and things, and if that's what people want to write about, it's cool to do that. But for me, this is extremely urgent. And I wanted to capture that intensity, that feeling of living through it. During the worst of COVID, you would wake up and it would just feel wrong, you know, I'm locked in my home, we don't know what's happening, and especially during the Trump years not knowing what insanity will be happening today, like I'm going to read the news to find out what the next insane thing that's going to happen is. So I really wanted to capture that feeling of living in a world that's out of control.

Has it always been important to you to address topical reality with Woe's music over something more fantastical, something more typical of black metal?

It's changed over the years. The first demo is pure Satan. The first album is a hint of Satan with more depression. For a long time, Woe was very inward looking, and it was very much dealing with questions of meaning and purpose and identity. Even then I tried to write about things that were at least a little relatable. I wasn't trying to be full on LiveJournal “here's the thing that happened to me today.” It was more that I am wrestling with these feelings of pointlessness and worthlessness, and feeling a lack of purpose in the universe. But I wanted it to be, again, for the reader or the listener to map to their own experiences.

So in that sense, yes, it's been important for me to write about things that have real meaning to me and aren't just scary stories, or spooky words strung together to create an atmosphere. I find it hard to scream about things that don't have meaning. I have a really hard time creating real emotion for things that don't evoke real emotion. Which, again, some people can do it and cool, you know, great. It's just, for me and for Woe, it takes things that are real to draw that energy, that real darkness.

We're so normalised to the sound of extreme music now that it's possible to forget the energy that's required to produce those sounds and the place they come from, so that's very understandable! I feel like you've always experimented within the scope of what a black metal vocal can be. On this album, the vocal has this strong, percussive element, and that quite a lot of the violence of the record is tied in there, this extra layer of rhythm on top. What was your approach?

Ah man, you're setting my day off to a good start here! So, there are a few things here. The first is just that sonically, I'm listening to more death metal, or I was listening to more death metal, than anything else for a while, and I've come to really appreciate and love the overwhelming intensity of the vocals. If you take typical black metal vocals, the traditional black metal high shriek, it's ethereal, and it's otherworldly; it can be ghostly. It's extreme, and it can be emotive, but it tends to be a whisper; it tends to be a voice on the wind; it has goals that are different to the goals of death metal.

A really powerful death metal voice is the voice of an angry God, it's this rumbling that comes for you and just gets in your face. It also feels more aggressive and more confrontational, so I was drawing a lot from that, also drawing a lot from the fact that no one sounds like a black metal vocalist when they are angry, I'm sure there is someone who you get them really pissed off, and they're like *gnarly* "What the fuck are you doing?" But for the most part, you get someone really furious, and they go low and booming, so I wanted a vocal that has that aggressive sense of some maniac, really up in your fucking face, so it's death metal plus aggression.

Musically, the rhythmic element? Yes, absolutely, I wanted that extra percussive rhythmic element. Because with a black metal vocal, you get a lot of dynamics out of it; you can do a lot of things with a black metal voca;. It has more subtle variations; you can tune it to different levels depending on what you need. Whereas a low vocal, something more guttural, tends to be a little bit more one note; it lives in a kind of narrow sonic range. For instance you can't do it quietly. So for me, the way to get more variation from it is to really hook into the rhythms, really dig into the percussion of it, to try to make the best use of it. As a drummer, I tend to think in terms of rhythm, and I put a lot of thought into the rhythm and the interplay between the vocals, and everything else.

Given your hand touches everything on the album, what tends to fall into place first?

Riffs. Guitar, everything starts with a guitar. For about 15 years now, I've used this particular recording software, a program called Reaper. And everything starts there. So it'll start with me and a guitar in the software with a click track playing riffs. For the past few albums, I've used programmed drums, so I'll program drums while I'm writing. So I'll write a few riffs, and I'll iterate on some guitar parts, and then I'll program the drums along with it, programmed the way I expect the drummer to play.

So I'll programme with me in mind, or I'll programme with Lev in mind and just build iteratively. So sometimes I'll do a few riffs at a time, or sometimes I'll do an entire song, then I'll go back and add drums. These turn into full demos, so if a song survives the early writing process, if I can complete the song on guitar and drums, then I'll go in and I'll put bass in and then at some point I'll add vocals to that demo.

On every album, these demos were then moved to the studio for the actual recording. Sometimes pieces of the demos will make it to the final release. But if nothing else, that original click track will become a thing we used to record, and while we're recording, we'll hear the demos and we'll be playing along to the demos, replacing them sort of Theseus style, replacing things one piece at a time until it's until it's a new song.

This album was a little bit different because of the addition of synth. So the synth on the album is taken straight from the demos, and when I was recording, I have this massive, single project for the entire album that includes all of the studio tracks, and then I can scroll down, and I've got all of the demos. In this case, every song on this album was demoed at least twice. So the project now has all of the studio recordings, plus the rehearsal space recordings. In some cases, there's a demo of lead and a demo of me. And then below that, we have the programme drums on top of it. So just a lot of iterations.

I hope that file was backed up somewhere.

Yeah, I'm a big Dropbox user. I have a gigantic Dropbox folder.

Regarding the final song on the new album, "Far beyond the Fracture of the Sky," we've discussed that the album is urgent; it's direct, and it's aggressive. But this song feels like a perspective shift, it talks about the ideas of parenthood and inheritance and there's this repeated phrase 'a world no child dares explore,' It just seems to have that little extra ounce of melancholy in there. Was closing the album on that kind of tonal shift deliberate?

I am touched and honoured that you hear that. Wow. Thanks man. Could not have said that or captured that better. If we think about the concept of the album and the chronological order; we narratively start somewhere with a lot of urgency and momentum, we talk about the thing that wakes up and people seeking to capitalise on it, creating conflict, and then resignation that follows in the song "Shores of Extinction" people becoming unable to change.

And then we end at a destination, we're going down a path and we're looking forward, and I think that was written from my perspective as the father of a young child. As I'm getting older, I'm finding that I am less in my head, less thinking about how I feel and thinking more and more about what do I need to do to provide for her? And what am I preparing for her to take over? I'm seeing this from the other side, my dad is in his mid 80s, and we talk about this a lot. And it's, you know, I'm starting to think about these questions, what will there be to inherit, is the question that the song asks, when the world is fucked up, like, what will there be? And we don't have the answer for that.

So it was definitely written with that in mind because after all the rage, it becomes the next question. So yes, that was very deliberate; that was very overt because it's on my mind all the time. And I think that it's something that a lot of a lot of parents will relate to. But I wanted to end on something that looks to the future and was less focused on the now. I think it makes sense narratively, but I also just needed to get that out.

I think it speaks beautifully to what you said earlier about heavy metal. It can be more meaningful if you've got something to care about, or something to be angry about. And it's such a good illustration of that.

I'm really glad you think so, I'm really glad that it comes across. I think that, for me, is probably the most meaningful song on the album. I'm not gonna say it's my favourite, I don't know if I can pick a favorite, but I think it is the most meaningful because it's the one that lingers with, it's the one I think about the most. Being angry about things is usually temporary, but that question about the future doesn't go away. What will there be to inherit? This is where we are, you know, I think we're headed towards a pretty dark place. And it just seemed like the right conclusion to an album that's talking about this, this lurch forward into the unknown.

…

Legacies of Frailty releases September 29 on Vendetta Records, and can be pre ordered here.