Master Boot Record's Dark Synthwave Injects Cyberpunk Into New Adventure Game "VirtuaVerse"

…

If you want a short version right away: VirtuaVerse, both the point-and-click adventure game and adjoining original soundtrack, are good. They are not only good, they are the current apex of synthwave as a genre, equal-footed sibling to the feature length film Blood Machines, which was penned by Carpenter Brut. Through these, synthwave as a genre fully extends into the two media formats that are most critical to it, with one exploring the profound influence of video games on the genre and aesthetic and the other exploring sci-fi and horror film.

One of the many appreciable elements of VirtuaVerse is how rich it is as an object, how many fruitful and satisfying disconnected strands of thought and influence come together in its creation. It was inevitable that we would receive a concept album that is a video game, rather than one inspired by games or inspirational for them. After all, we’ve gotten all kinds of other variations on the form, from stage productions from Dream Theater to graphic novels from Coheed and Cambria and more — even Blood Machines, equal in quality to this project and perhaps more approachable as a roughly hour-long film, is not unique in being a film-length project born from music.

VirtuaVerse seems to be the first concept album released as a video game as its original format, deserving not just a review of the game and music itself but also a deeper look at the relation of games and heavy metal (and how a project like this came to be in the first place).

The charms of VirtuaVerse start at its title screen. After the requisite short intro film and publisher logo splashes, VirtuaVerse greets you with a detail-rich depiction of a classic late 1980s or early 1990s computer desktop setup, complete with oversized and overweight CRT monitor, a horizontal tower complete with a floppy disc drive, and a veritable treasure trove of curling sticky notes, half-finished cans, and partially-posed plastic figures.

Each of these items is a clickable link, be it to the developer’s website, Master Boot Record‘s Bandcamp, the label’s site or more. This kind of detail-rich opening menu screen has been in vogue for some time now, showing up in places as varied as indie darling Surgeon Simulator and AAA mega-smash Call of Duty: Black Ops. It’s a form meant to indicate that even on that first meaningful click that the project to come is one that values small details and completeness of vision rather than just a streamlined central experience with minor set dressing.

That sense of richness of detail and fineness of filigree, with the above being just one example, is one that runs through the entirety of VirtuaVerse, both as a game and, more importantly, as a game-as-album.

…

…

It’s fitting for the genreform of the game that this collaboration would so highly value keen detail work. Point-and-click adventure games are a genre not typically predicated on length but rather their depth, swapping out the sometimes endless cutscenes of JRPGs or continuous online play component of multiplayer-oriented fare with a keenness of writing and cleverness of puzzles.

VirtuaVerse doesn’t skimp in this department, clearly designed with thorough notes of the LucasArts classics like Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis and the Monkey Island series, and with a decent share of red herrings to boot. The one relatively major change for people used to this style of game are the various quality-of-life improvements all across VirtuaVerse. For one thing, it seemed on my playthrough that there were no out-and-out wrong answers to puzzles, nor successful combinations of items that yield no results. What this means effectively is that, for those among us untrained in the galaxy-brain mindset needed to approach most point-and-click adventure games, you can effectively brute-force the game.

This is less satisfying than cleverly ascertaining what needs to be done, of course, but it also means that the game can be completed comfortably in the ten-hour window rather than some of the harder games of this genre which can slog on for 20 or 30 hours not because they are long but because you are just plain stuck.

The logic behind the puzzles of VirtuaVerse is also substantially more forgiving. While characters do not often out-and-out state exactly what they want from you, nor do environments place a big blinking arrow over items of interest, the scenario writing is clear enough that a cursory scan of your inventory and the area will quickly map out who needs what and when. Compare this to the sometimes exceptionally abstract puzzles of the Monkey Island series, where in one passage you must put a ship’s anchor into a key lime pie and hurl it at a mime to get a prize.

I’m not saying there is no one on Earth who would think to combine an anchor with a pie, but I recall when I was younger spending a good two or three days stuck on that particular puzzle because, pitiful human mind-thinker that I was, I never would have thought to combine the two until my good friend who’d already completed the game clued me in on it.

This brevity — a $10 game that you are able to 100% in roughly seven hours — may feel scant, but VirtuaVerse prides itself on density over length. If we are honest, video games often pad out their length with meaningless collect-a-thons, aimless open-world map-filling and side quests that offer little save more ways to fiddle with the controls. VirtuaVerse, meanwhile, is as tight as the bulging muscles beneath a bodybuilder’s taut glistening skin, functioning more like a long interactive film due to the satisfying combination of its density and legible puzzle logic.

This sense of density also helps highlight the strengths of the writing and worldbuilding. The world of VirtuaVerse will be immediately recognizable to anyone who’s even so much as browsed the “cyberpunk” entry on Wikipedia, but while it may be tempting to knock off points for unoriginality, the game clearly communicates that it’s more interested in a concentrated aesthetic experience than in being groundbreaking.

It is fair, of course, to want new and exciting ideas, be it from games or music or film or any other artistic medium, but there is a value as well to well-crafted honing of existing ideas, especially if they are clearly communicated as aesthetic/genre experiences and not pretentiously preening as groundbreaking fare when they aren’t.

…

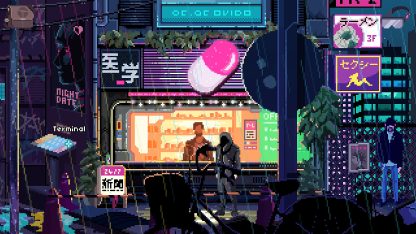

VirtuaVerse Screens

…

In this capacity, VirtuaVerse‘s bonkers plot, which over the course of the game tilts further and further toward hallucinatory cyber-shamanic Cronenbergian flair, certainly satisfies. The game is even wise enough not to linger too long on the sometimes boomerish or mildly problematic portrayals of things like sex work, indigenous people, shamanism, phone/internet addiction, or the like, making damn well sure to present the protagonist as too fucked up, destructive, and self-centered to be much more than just another perspective among many.

And it’s worth noting that the main character is a real piece of shit. There are multiple moments where your actions lead to the deaths of minor characters or the destruction of their livelihoods, all of which main character Nathan shrugs off with only a minor twinge of regret. The means justify the ends to him and, as ugly as the world is, it’s only ugliness that gets you through to the other side.

The game, meanwhile, has a slight narrative remove from these actions, using short cinematics to make you confront how truly fucked up and self-centered Nathan is being and how little he seems to regret any of it. The slight removal of agency caused by the genreform of point-and-click adventure games also helps cut the tendency for this type of writing in games to become tedious and moralizing like Undertale at its worst or, moreso, something as boorish and thin as The Last of Us, a game which simultaneously forces you to be violent while chiding you for it.

VirtuaVerse by dint of its form is not a game of you playing as Nathan but more you suggesting things to Nathan, such that when he acts selfishly against your own morals as a player, it feels more like reading the bad actions of a character in a novel or in a film. It doesn’t feel like the game is chastising you as much as remarking on this type of self-centered, self-elected “hero” figure who (minor spoilers ahead, sorry) winds up maybe just making everything worse rather than making anything better. The lensing is deliberately somewhat ambiguous; it’s a nasty, fucked up world Nathan lives in, with pushers and killers and abusive corporations and fascist cops and more.

But it also doesn’t cut him any slack for the things he does in response to that world. For instance, he continuously baselessly accuses his girlfriend of cheating on him, something she vehemently refuses and at times chews him out over. You can see where his thoughts come from, but not from a place of sympathy; he is endlessly insecure in a way that seems to drive his narcissistic destructive behavior and so, when you finally get to play as his girlfriend in a brief segment set (sit down for this one) in an underwater nuclear missile base largely battling a giant octopus, you begin to really sour on how shitty he is to her.

When Nathan’s actions lead to the permanent psychosis of a homeless man, it feels awful; when he destroys the pride-and-joy drone of someone he only acquired by getting them black-out drunk, you feel like a monster.

You destroy a band’s life in order to functionally steal their bus all after you arrange to have a man pledging to join a gang killed by gunfire all so you can rifle through his pockets for a badge. That things end poorly for Nathan in the end feels sour, almost too dark to be bittersweet. But it also chiefly feels deliberate. Cyberpunk within VirtuaVerse still at least holds some semblance of punk spirit, and so the long hard look at the vile things people give themselves license and excuse for feels like one of its chief thematic criticisms. Couple that with the hysterically surreal and bleak ending and it’s hard not to walk away satisfied.

It is during the final credit crawl that VirtuaVerse reveals one last trick. It is not, it turns out, a game made by Theta Division and scored by Master Boot Record. Or, rather, it is, but this presents things in the wrong relation.

…

…

Up until that point, I was under the impression that this was to be an interesting formal experiment for Invisible Oranges, another step in our continued light experimentation to see just what a metal website can satisfactorily cover, what tendrils of heavy metal culture and influence (in either direction) we could grapple with satisfactorily.

I discovered that Vittorio D’Amore, also known as Master Boot Record, had not only developed the original concept and penned the story, he had also aided in the game design and dialogue writing of VirtuaVerse. He had done this, it turns out, because he is one of three members of Theta Division. In retrospect, this shouldn’t have been shocking; frankly, I had wanted a fresh and unhindered look at the game and its soundtrack and so, after taking the assignment, I deliberately dove in blind.

My notes, then, which constitute the review of the game at least, are based on that relatively blind experience, taking the game for what it was before me rather than having the better-shaped understanding of what I had just played that came from completing it and seeing that little bit in the credits roll by. The late-stage revelation to me that VirtuaVerse was not a game with a soundtrack by a chiptune/industrial metal artist but in fact a game-as-album felt like a rattling and satisfying sea-change in my perception of the project, something that nudged it from merely really good to highly recommended.

It makes sense, structurally, for someone related to synthwave to eventually produce a game. Hell, heavy metal and games in general go way, way back. Doom and Doom II, the legendary first-person shooters of the early 1990s, famously had a soundtrack at least partly composed of straight-up stolen heavy metal tunes rearranged for the buzztooth synth sound of Creative Labs Sound Blaster soundcards, with songs from groups as big as Metallica and Pantera getting that retro/bitcrushed treatment.

This event had three notable off-shoots:

First, and most obviously relevant for VirtuaVerse, it was that precise decision that generated the fundament for synthwave as we know it. There are other influences in the pot as well, obviously, from the leather jacket stiffened cool of Judas Priest to the broader world of chiptune and video game music (especially of the 16-bit era) to the classic cybernetic kosmische horror and sci-fi soundtracks of artists like John Carpenter, Vangelis, and Tangerine Dream. But without the iconic heavy metal soundtrack of Doom, of which its massively influential opening level’s piece “Hangar” is a barely-disguised version of Slayer’s “Behind a Crooked Cross,” it is highly unlike the specifically metal-inclined vein of synth music found in synthwave would ever have come to be.

Second, the success of Doom as a franchise plus the increasing notability of its stolen music pushed id Software to go for the real thing for its spiritual sequel Quake, where they famously commissioned Trent Reznor to record a full original soundtrack for the game. Reznor’s soundtrack, released between The Downward Spiral and The Fragile, was received with rapturous praise, living comfortably alongside the other albums of that early hot streak of his.

The third offshoot of Doom‘s stolen metal tunes built upon both of the previous fruits of that action when, in 2016, the rebooted Doom installment was announced to not only have an original heavy metal guitar soundtrack composed for it but one that was also to be procedurally interwoven into the fabric of the game itself. One of the trickiest components of soundtrack work, and something you have to be mindful of when either critically reviewing or even just casually listening to soundtrack material, is that it is made to live within the source context. Often, compositions for games or films will have deliberately curated senses of spaciousness and emptiness that should critically not be viewed as a gap or empty space within the song.

These spaces are meant to be filled with diegetic sound, be it the sound effects of a video game or the dialogue and scenery sounds of a film, offering a fullness in context that often cannot be fully created outside of that context. This is ultimately why certain punk, grind, and extreme metal bands began interpolating film samples and the like into their work, all an effort to replicate the implicit sensory overload of a well-arranged soundtrack/visual-ludo media interconnectivity.

This original procedural heavy metal guitar soundtrack for both Doom 2016 and its sequel Doom Eternal offer a direct connection in the interrelation of metal and games explored in VirtuaVerse, one where it suddenly feels wildly improper to view the game and the soundtrack as separate, one derivative of the other.

…

…

It is tempting to compare VirtuaVerse to the other wing of relation of metal and video games, that of the game derived from the music and not the other way around. We have more examples of species in this space that you might immediately assume. Iron Maiden, for instance, have been hard at work in this arena, with entries such as the first-person shooter/greatest hits game/music collaboration Ed Hunter that celebrated the return of Bruce Dickinson to the band, the top-down Asteroids-like packaged with The Final Frontier‘s special edition, or the surprisingly competent gachapon smartphone RPG Legacy of the Beast.

Likewise, I wrote some time earlier about Amon Amarth’s platformer for smartphones, a game that attempted to justify a nearly ten dollar price tag with at least the premise that it was a fully-realized game.

These attempts at synthesizing games and heavy metal music live on the other side of the fence from the world of Doom however, not satisfactorily moving the ball forward on a synthetic and syncretic hybrid of the two but instead inverting the process, music being the groundwork for a new game rather than an equal partner in its object-form. Hell, even Double Fine Productions’ Brütal Legend, a thoroughly composed AAA real-time strategy title built off of the backs of dozens of heavy metal songs and figures, still ultimately felt (among other shortcomings) like a list of songs of interest to the developers rather than an equal-footed partnership of music and game.

VirtuaVerse the game is, critically, the album itself. The game acts as an efflorescence of the concept of the piece, taking the dramatic thrust of works by King Diamond, Dream Theater, Nocturnus, Queensryche, and more and taking it to the ultimate apex that something like synthwave demands. Where Doom, Quake, Hexen, and the eventual Doom remakes all sought to transform material from the worlds of death, dark ambient and thrash metal into subject for their hyper-violent odes to the ecstasies of those genre spaces, VirtuaVerse instead lives within a space that tends to be retrogazing, reconstructing a hauntological future rich in the past.

It becomes fitting when, textually, a great deal of VirtuaVerse the game becomes about recovering and utilizing old technology and hacking methods more likely to be found in The Anarchist’s Cookbook than a modern-day dark-web Tor-accessed site. It likewise makes conceptual sense as well that Master Boot Record and Theta Division would choose point-and-click adventures to be the platform for expanding their concept record into a full playable game. Where fellow synthwave artist Carpenter Brut expanded the lore of the video for “Turbo Killer” into the feature length film Blood Machines befitting the explicitly cinematic thrust of his approach to synthwave, Master Boot Record has always premised itself on computers and computer life, especially that of older technology.

VirtuaVerse is a good, solid addition to the genre it bases itself in, and the music packaged along with it not only does a damn fine job of evoking the cold, ruthless cybernetic cool of a grimy and amoral cyberpunk future, it also holds up well under the scrutiny of an isolated headphone listen. But perhaps more importantly, in a world where anyone can record a record at home and release their record to Bandcamp, VirtuaVerse as an overall project affirms the power of going that extra mile for a project.

This is not meant as a slight to those lo-fi and street-level offerings of others, and often even this type of extended production would be ill-fitting for certain groups or projects of that type. But it is hard to separate the intense satisfaction I feel viewing VirtuaVerse as the ultimate summation of Master Boot Record as an entity, strong enough that D’Amore could feasibly retire the project and rest easy knowing the mission was completed.

This sense of overall aesthetic completion is so incredibly rare and, frankly, many artists don’t tend to even try. VirtuaVerse deserves more than for someone on a website to sit back, say it’s pretty good and call it a day. This is a special project, deserving of thought and rigor and the same type of love that separated-at-birth sibling project feature-length film Blood Machines seems to be receiving.

Hats off to you, Master Boot Record and Theta Division. You did a damn good job.

…

Listen to the VirtuaVerse soundtrack by Master Boot Record on Bandcamp; it was released May 12th via Blood Music. The game is available on Steam.

VirtuaVerse Screens

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.

…