"A Feast On Sorrow"'s Profound Anguish is a Bold Step Forward for Urne

It can often feel like the darkness is winning. Metal’s greatest power is its ability to turn pained feelings such as this into ecstatic catharsis. It gives shape to the void, when it can feel like the viscous black is all-consuming. A Feast On Sorrow, the latest from London metallers Urne, will resonate with anyone who knows of this darkness. An intensely personal album that thoughtfully ruminates on terminal illness, it’s an anguished voyage, but one that reaps great rewards.

Produced by Gojira’s Joe Duplantier, A Feast On Sorrow possesses a heavy, tortured heart. However, it expresses these knotty emotions like all the best and most resonant metal via great riffs, stirring vocals, and titanic production. Signed to Candlelight Records (part of the Spinefarm Music Group and a subsidiary of Universal), Urne’s blend of classic and technical metal has the potential to find the band an audience beyond the limits of the genre’s underground.

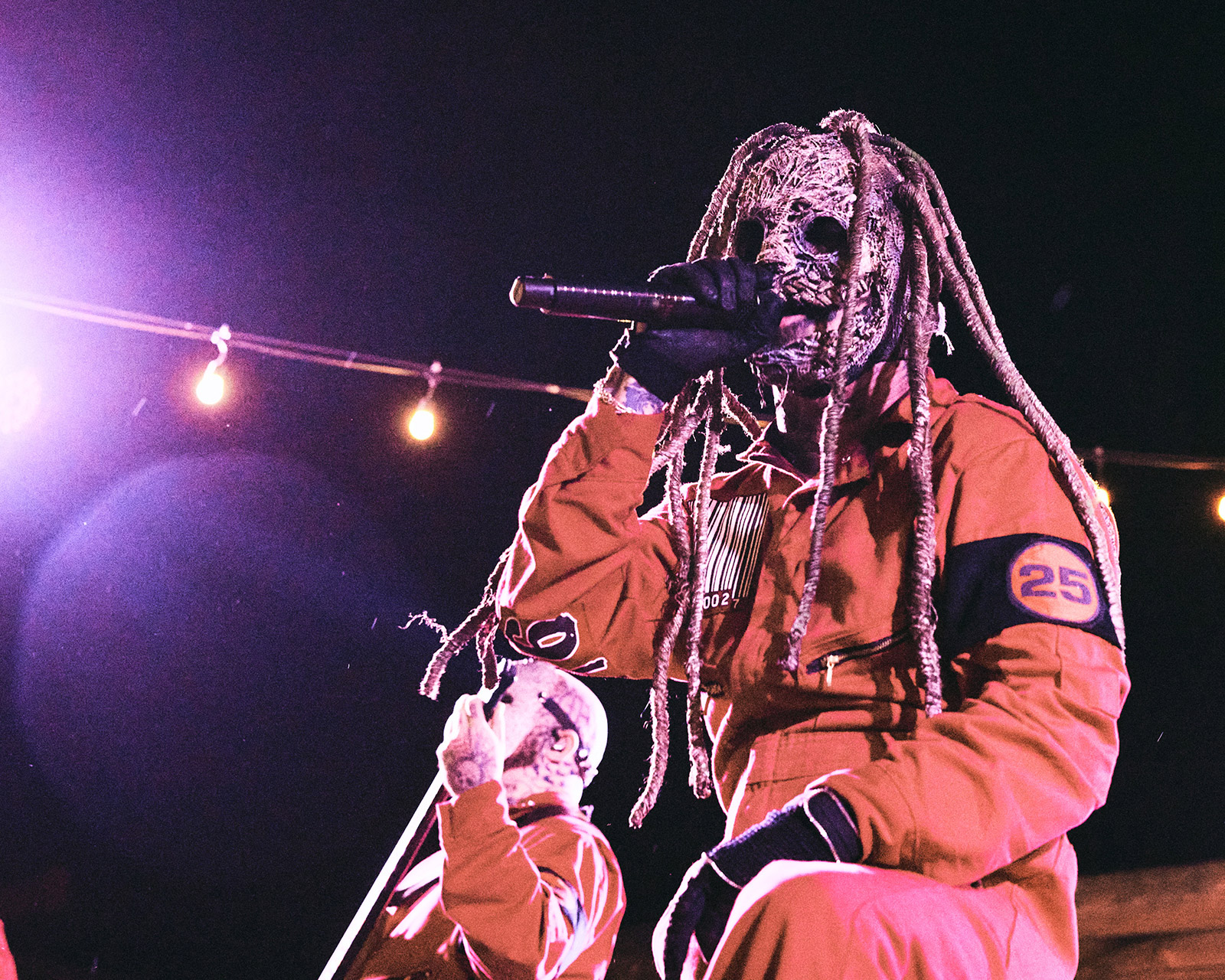

We spoke to Urne frontman and bassist Joe Nally about his band’s rise, working with metal royalty, and A Feast On Sorrow’s weighty thematics.

…

…

To elucidate your background, can you tell us a bit about your previous band Hang The Bastard?

Myself and Angus (Nayra, Urne guitarist) were initially in a more prog-y band, which has kind of become Urne. We went on tour with Hang The Bastard, and they asked if I wanted to join, and I thought, “Yeah, I can do two bands.” But then the first two years were pretty full-on, and I let my focus slip. Annoyingly, we only did one album, but the album that I started writing for that didn’t happen turned into some of the songs on the first Urne EP. It was a great band to be in. They’re back now, with three of the original members, but I’m not involved.

So when you started Urne, what did you want to do differently?

Initially, it was about cutting it down from five people to three. Best thing I’ve ever done; I wish I’d always been in a three-piece. Also, previously, myself and Angus had been in more technical bands, and we wanted to get back to that. First we needed to get our chops back. We had to get our hands back after doing power chords for so long. We wanted to challenge ourselves because we had four, five years out from doing this sort of thing.

Your first full-length came out in June 2021, right in the middle of the pandemic; did they change or dampen anything to do with its release?

To be honest, for the first six months of the pandemic, I was living down by the coast where we had the lowest cases in the country. I’d walk down to the beach every morning with a coffee, listen to some Alcest, and do some work. We finished writing the album remotely, even though I’ve never liked that, and we managed to get into our practice room for a couple of long sessions, so we said, “Fuck it; let’s make it.” As bad as the pandemic was in so many ways, it did let us put together an album. We also got on some of the few tours that were happening—Orange Goblin, which was right after the first lockdown, then Devil Sold His Soul, which ended the day the Omicron lockdown started.

You mentioned writing stuff remotely; can you tell us about your writing process?

So me and Angus always used to write together. Now, it’s a bit different. I’ve moved out of London, though I still work there, so we do still manage to jam. But there’s also a lot of voice notes—playing a bass riff, singing a vocal line. We’ll end up with a library of stuff, and me and Angus will go through them and say “shit” or “not shit.”

For this album specifically, does the finished project resemble the thing that you envisaged when you were putting it all together?

Some elements of it are different. But once we got who we wanted to record it in mind and said to them, “We like what you did with this,” we knew it would sound heavy and massive and I think got pretty close to the thing that I envisaged. Because of the team we had, I knew it was going to sound fucking alive and organic.

Do you feel like this album is a step forward for Urne?

Yeah, I think so. On the last album, there were four or five good songs and three really good ones that were us at our best. We focused on those, which were the best of what we do. We knew it was going to be heavy after writing two songs, so we stayed on this especially intense sound. Honestly, it really feels like a step forward; the technical passages, songwriting, production, vocals, drums, riffs are all much better than the last album.

So how did Joe Duplantier get in contact with you?

Joe reached out and told us that he liked what we were doing. We had a little conversation, and I asked if we could use his studio to track drums. Joe doesn’t produce many bands, but he said he was interested. Fast forward 10 months, and we’re walking through New York City saying, “I can’t believe this has happened to us.”. It still seems surreal, even though we talk and have done shows with them.

What kind of producer was he? Did he want to help shape the songs, or did he focus more on the technical side?

He didn’t touch the songs; he wanted to build a sound. He wanted to give us an atmosphere and a personality. He wanted to try weird things: add bits of percussion, try out loads of tones. All the drums were done live in the room with us playing with the aim of keeping everything as real and as authentic as possible. Even though it sounds so massive, I also think it has an energy where you feel like you’re sat in between three guys going mad playing technical metal. I think he smashed it.

In as little or as much detail as you want, can you talk a bit about the background to some of the themes that you’re looking at on this album?

It’s a personal one. When we started writing it, illnesses were affecting members of all our families. In my immediate family, two people have the same terminal illness, and one has recently passed. The album deals with getting told you’re about to go through several tough years that will inevitably end with sadness. It’s about the whole process from when you find out, to the song “Peace,” which represents the moment someone passes. Compared to anything I’ve done before, this is the most direct I’ve been in terms of lyrics. I didn’t feel pressured when writing them or in the studio, but every time we release a song, I’m feeling the pressure.

There’s a starkness to the album’s aesthetic; the roomy production, the cold artwork. It’s hallowed. I interpreted that as a representation of what you must be going through.

We were struggling with the artwork, but I had that image saved somewhere. I kept looking at it, and the color was what I felt and saw when I listened to the album. I have the vinyl here, and it makes me feel like, as a metal person, I want to know what’s inside it. It feels powerful, and I like to think that we wrote something as powerful as the artwork.

Urne seem to move fast; are you already imagining what comes next for your band?

Yep. I can’t write anything for the next album until this one’s out, although myself and Angus did come up with one song by mistake a few months ago. We always have conversations when we go out for a pint about what we want the new one to sound like and what we can touch on that we haven’t already. We used to play more prog-y stuff. I think that’s something that Urne hasn’t touched on yet, although we need to do it naturally and organically. I used to have strict rules, but now I just think “whatever happens, happens.”

…

A Feast On Sorrow is out today via Candlelight Records.