The Read Chord: Interview with Dan Fante

Welcome to The Read Chord, Invisible Oranges’ new column about reading. The material may or may not be about metal, but will be of interest to fans of metal. Writers on staff and guests will pen the column. Readers can also take a whack at it. (For proposals, email invisibleoranges at gmail dot com). Metal is more than music; if I went deaf, I would “stay metal” in other ways.

One way would be to read more Dan Fante. His book Chump Change is the only art that has made me fear its brutality. No metal has done this; no horror film has done this. The book is a free-fall descent into addiction and emotional depravity. It is a sort of “gore noir”, the death metal to Dashiell Hammett’s Black Sabbath. But the gore isn’t fantasy; it comes from Fante’s life. In this interview, Justin M. Norton talks with Fante about drinking, more drinking, and redemption through art. – C.L.

. . .

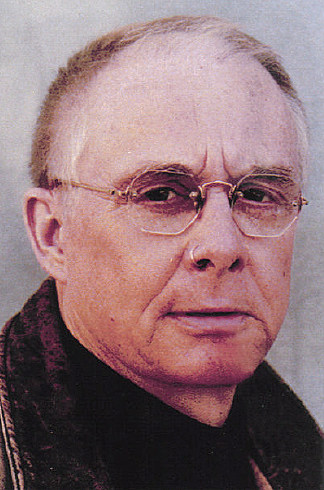

Metal deals with the most extreme elements of life: depression, rage, addiction, and despair. Novelist Dan Fante has experienced all of the above and more – yet survived and forged a successful writing career in his 60s. His compulsively readable books would suit souls who find salvation in blastbeats and riffs.

Most of Fante’s novels are narrated by his autobiographical character Bruno Dante. Dante is an addict, a misanthrope, an unreliable friend and romantic partner, and a supremely bad employee. In Fante’s latest novel 86’d, Dante is back home in Los Angeles and seemingly on the path to stability and success when his demons get the better of him. Dante soon resumes his old life of blackouts, blowups, and lost opportunities. At one point, a jealous lover superglues his penis to his leg when he passes out.

Fante is the son of legendary author John Fante, who wrote the classic Los Angeles novel Ask the Dust. In some ways, his literary pedigree has helped him, and in others it’s been a roadblock. Could you imagine Wolfgang Van Halen shining on his own outside of his father’s accomplishments? Yet Fante has managed to carve his own niche, despite his father’s imposing literary shadow.

Fante’s life is stable now, even happy. His fiction is published via a major house (Harper Perennial). He is a loving father and husband, and he reaches out to readers who struggle with addiction. He is writing a memoir about his famous father after years of struggling to make a name for himself. The icing on the cake? The major press re-releases of Chump Change, Mooch, and Spitting Off Tall Buildings, the first three books in the Bruno Dante series.

. . .

INTERVIEW: DAN FANTE

A SURVIVOR’S TALE

. . .

. . .

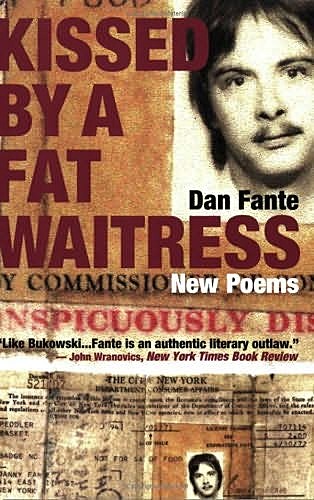

On the cover of your poetry collection Kissed by a Fat Waitress, there is a photo of you from the early 1970s. Where was Dan Fante in his life when that photo was taken?

If you look closely, it’s a peddler’s license photograph. Where was I? I was a wackadoo. I was a street peddler making a living beneath the radar in New York and getting busted one or twice a week and drinking myself to sleep every night. For a while when drinking worked, I was having fun. I was making a lot of cash, I was my own boss, and I had the money to produce and tape a radio show because they didn’t pay me enough to cover the expenses. It was actually a good period. I was writing and drinking and pretty productive.

At the end of your latest novel 86’d we find your autobiographical narrator Bruno Dante closer to redemption than perhaps he’s even been. Will we see more of Bruno?

The real answer is that I’m not sure where I’m going to go with Bruno, if in fact this is the last one. I have an idea for one last novel. It just depends. I think I want to write a play next, and I’m writing a memoir. If the novels sell well and there seems be an interest in another one, then I might write the last one.

At one point in 86’d Bruno rages about the Internet and computers and even throws part of a computer at a neighbor out of a window. How do you feel about the digital age and the Internet and what it has done to writing?

I think anything that improves communication improves literature. But there’s going to be a lot of slop. I get a lot of e-mail. And an agent or someone talked me into getting Facebook. With the e-mails I was answering and Facebook, I was losing my sanity. Then someone stole my identity on Facebook and was using my name. I found out that was being done and just bailed.

Still, whatever improves literacy is a plus. My friend Tony O’Neill (author of Down and Out on Murder Mile) says that my kind of literature is the new rock-and-roll, that the kinds of books we write attract another culture. I support that idea, and I hope he’s right.

. . .

. . .

Do you hear from a lot of people who identify with Bruno Dante?

I did an interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s “Fresh Air”. I had no idea the audience it reaches. I got maybe 50 e-mails, and I answered them all. There were people who didn’t know my e-mail address and had to research it. So that was pretty gratifying and shows you the quantity of an audience willing to go online and interact with an author.

What were people saying?

There’s a strong identification with my stuff. It resonates. When you write from the gut and the heart, people get that. I have a lot of people who said, “You really spoke to me, I used to be addicted, and I was an alcoholic”. I heard from guys that had been in jail and guys on the nickel in downtown L.A. It was very gratifying. It wasn’t the kind of literary praise that a mystery writer gets. It was very personal.

Some critics have said that Bruno is too self-destructive and narcissistic to relate to.

I wonder about the critics who read my work and their background. My books are constructed in two ways – I never flash back or expand on characters. The narrative goes from start to finish. My hope is that readers can read it in one sitting. I want it to be fast. There’s a very dark strain of humor in my stuff, and people who have the kind of background I’ve had can identify with it. I’m trying to speak directly to people.

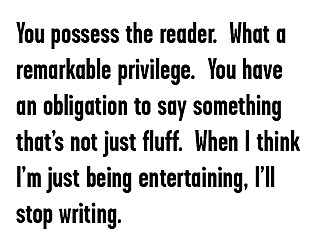

Did you ever see the movie Alien? A novel is like that alien attached to someone’s face. You possess the reader. What a remarkable privilege. You have an obligation to say something that’s not just fluff. When I think I’m just being entertaining, I’ll stop writing.

Your books were popular in France before they ever got picked up in the U.S. Why do you think your books caught on overseas first?

The French like something dark and something that digs beneath the surface. I immediately had an audience. What’s interesting is that I sent that book (Chump Change) out 40 times in America and I couldn’t find an agent.

. . .

Fante on honesty and emotion

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSopDTLlkA8&

. . .

When you were working all of these odd jobs throughout the years, did anyone ever have an idea that you were a writer or that your father was John Fante?

When I lived in New York until I was 35 years old, no one had heard about my father. In the mid-’70s John Fante was an ex-screenwriter on Social Security.

Bruno goes through so much, but what was the low point for you? Hospitalization? Moving back home at middle age?

Some of us sort of skid along the bottom. My low was the limousine business. I had this great company and I pissed it all away. That was a serious bottom. I went broke, and then I got sober for a few years and got into the telemarketing business, and I started making more money than God. I was so afraid of failure, I wouldn’t get off the phone. Then I screwed that, too. I started getting drunk and doing dope again. I tell people I went to a Christmas party in 1964 and arrived home in 1987.

How old were you started writing in earnest, and were you sober?

I was an unemployed actor, and I started writing when I was about 28. I had an acting group, and we’d do scenes from a play on the radio for an hour at like 4 a.m. Only the walking dead were listening. The producer asked me for something original, and I wrote a radio drama for a few years, and it got a lot of attention. It was like 1971 or 1972. Then, I got in an argument with a guy that wanted to syndicate the show and I told him to go fuck himself. I just got drunk at the meeting. But that was serious writing in the sense that I did it every Monday night for two years. But when it blew up, I didn’t write seriously for years and years.

I was 42 when I got sober. I was 45 when I started to write fiction and really crazy. I was four and a half years sober and suicidal, out of work, and almost homeless except for my mother. I wrote Chump Change as kind of a therapy, something to do so I wouldn’t blow my brains out.

Why did you finally stop drinking?

I stopped just after I lost my telemarketing job. For the next few years, I kept going broke, but I wasn’t drinking. People were putting up lots of money for me to run telemarketing operations. They kept going broke. I just couldn’t lie to people anymore on the phone. I got to the point where I knew I had to have a new option. I was sober, but I’m sure I was clinically depressed because I was suicidal for a year and half. Nothing had changed in me, and nothing had changed spiritually. I still had the mind of a drinking alcoholic, and it was like being eaten alive by your own imagination.

This guy talked to me, and he had a few guys he’d worked with who had killed themselves. He said there’s another way, and you better find it. I didn’t even like him, but he rang my bell, and I kept going back and seeing him and talking about recovery.

. . .

. . .

How did you make the move from the small press to Harper Perennial?

My editor at Harper Perennial is a woman named Amy Baker. She liked my stuff. I had given up any idea of being a mainstream writer. I know I’m an acquired taste, and you better be ready for a ride. Amy had worked at used bookstore and had read my books. She later got to be an editor and marketing director at Harper Perennial. She submitted my books to the committee. She said if you’ll give us a new novel, we’ll publish it and publish the other books.

No one was more shocked than me. You have to have a champion somewhere, someone who thinks there is something marketable about your work. God bless her, she stood behind my stuff.

You are now working on a memoir about your father. Can you tell me more about that project?

There’s been enough written about my father, maybe a half-dozen books. There’s some misinformation about my Dad. I wanted to set the record straight, and it seemed like a natural outgrowth of the work I’ve been doing because my fiction is personal fiction. I had grave reservations, because a memoir by its nature has to be linear, and I’ve never been confined by a form before. I had to work my way through that. But I like the book, and I’m doing a polish on it before I send it in.

Do a lot of people find out about Dan Fante through reading your father’s work, or are readers coming to your work independently?

It used to be they got to me through John Fante. Now it’s about 50-50. I’m in bookstores. and you can get my book. When I was still with a small press, the wonderful Sun Dog Press, you had to find John Fante, look him up on the Internet, and my name popped up. So a significant amount of people read my father and then read me.

We don’t appeal to the same audience. It took some time to develop my own readership. Now some people see my work, then read my father, so the balance has shifted.

. . .

. . .

Your father also valued the simple, straightforward sentence. Was that one of the lessons he taught you when you decided to tackle prose?

The best advice I ever got is to emulate someone’s style as closely as you can. In emulating that style, you are giving birth to your own. If you read Knut Hamsun and then John Fante, you will see a similar style. When I was a kid, one of the first things I read was Ask the Dust. When your father is a writer and the conversations around the house are about literature and the medium of the novel, you get things by osmosis.

You live in Arizona with your wife and young son and even wrote a poem about how lucky you feel to be in the position you are now. Do you ever think about the dichotomy of your old life and how you live now?

It’s like being a schizo and being cured. My mind can still think that way… vengeful and angry. But that’s not my life. I think in that first book Chump Change, it didn’t occur to me that what I was really doing was pouring all the rage and all the unhappiness onto paper, so I wouldn’t have to deal with it. Writing has been transformative in that sense. While I stayed sober, I kept writing. I could visit that character in my work, but I didn’t have to be that character in the street.

Where does Bruno Dante end and Dan Fante begin?

We’re the same people. It’s autobiographical fiction. The difference – and this is my 64 dollar secret – is that the books are about a personal change. You were right about my books – there is a move toward redemption in all that stuff. There is something Bruno is reaching for in all the books. I am writing about the human spirit and a character surviving his personality.

. . .

Dan Fante official site

Dan Fante books @ Amazon

. . .