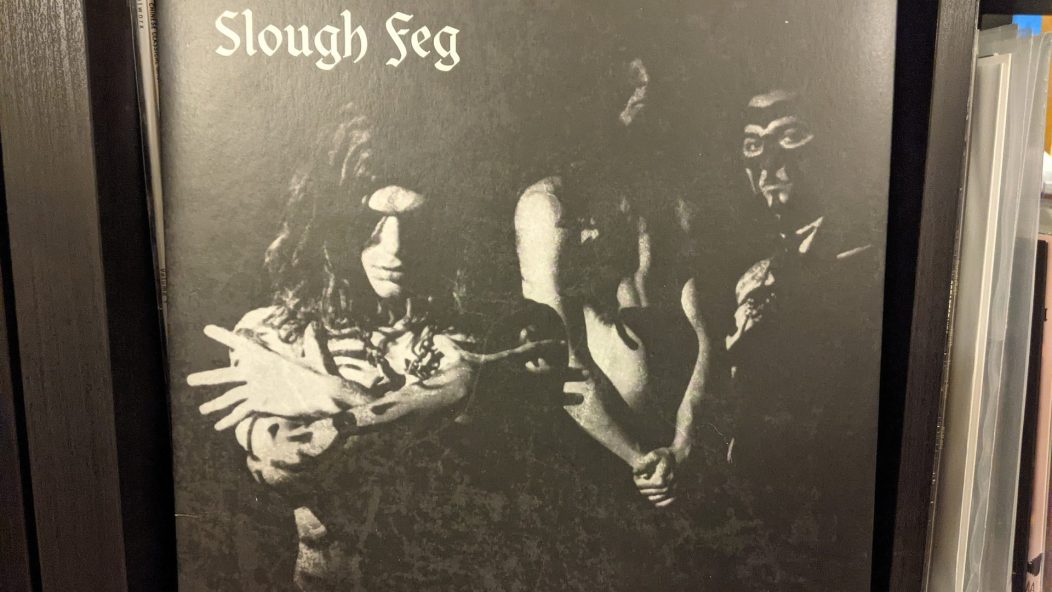

The Lord Weird Slough Feg's Fiery Debut Turns 25 (Interview with Mike Scalzi)

It’s tough to understate the importance that The Lord Weird Slough Feg (shortened for most of the article, and much of the band’s career, as just Slough Feg) has had on my life musically. Back in my freshman year of college, they personally got me into heavy metal; I was coming off a high school length obsession with extremity that had me ignoring anything with actual singing, and outside of the isolated Maiden or Sabbath songs that I grew up with I mostly just ignored heavy metal altogether.

All of that changed when I heard a Slough Feg song somewhere in some forum or another. Suddenly it clicked and first I was rabidly devouring everything Slough Feg had done, and then Brocas Helm, and Cirith Ungol and Manilla Road, and the rest all followed from there. My first short-lived band a year or two later was called Skyway Corsair, from a lyric off Traveller (“Only the wayfaring patron would dare—a merchant cruiser, a skyway corsair!”), and the fanzine I run is named for a song off their first album, as is my stage name—though they’re not the only band that’s been important in my musical journey, it might have all been different without them.

Long before I got into them, Slough Feg’s career started all the way back at the beginning of the 1990s. Years of demos culminated in 1996 with their eponymous debut album, The Lord Weird Slough Feg, which has now been out for some 25 years. Though the album is sometimes dismissed as primitive by well-meaning fans that prefer the polish of Traveller or the manic catchiness of albums like Twilight of the Idols or Down Among the Deadmen, the self-titled has always had a special place in my heart.

The songs have a certain frantic energy, and an almost anxiousness—to be heard, to express the band’s heart and soul—that makes it stand out even in the midst of Slough Feg’s long and industrious career. Raw power and the expressive nature of the material burn it into the mind, be that with the more lyrically gymnastic approach of a song like “Why Not” (“The world is watching down on you. The world owes you nothing, but you owe it nothing too”) to the simple, emotional and hoarse delivery of the two-word chorus of the album closer “Highway Corsair.”

There’s a lot more that could be said about this album, but Mike Scalzi, the band’s main man and guiding spirit through the years, said it all in an extensive interview about the album and said it better than I would have. Read on to dive into one of the most weird and wonderful albums in the history of heavy metal.

…

https://youtu.be/4bv2iz0fLmg

…

Hey Mike, thanks for taking the time to talk about the first album!

I’ll ask you the first question! I’ll interview you! No, really. You said something like it’s the 25 year anniversary coming up in May? Did you say that?

Yeah! It’s been 25 years. I can’t find the exact day anywhere online but…

There isn’t one. I mean, that’s why I was confused that you said May, because how do you put any kind of time on it? The album technically didn’t come out at all. The album was self released, and I mean yeah, it’s definitely 25 years, but there’s no month that it came, you know what I mean?

What you’re telling me is that some asshole at some point went in and marked that this album came out in May?

[Laughs] Oh really? Is that what it is? Where does it say that?

It’s on the Metal-Archives and Discogs.

Oh really? On both? Someone just did it.

Somebody probably referenced the other one.

And the first person either just made it up completely, or maybe that’s when they got it? From me directly maybe. Just got it from someone in May of ’96, maybe, even though that would be really early I think, and then just decided that’s it. Because there was no official date. We made the record maybe a year or six months before, whatever it was. I think it was recorded in ’96, and then sent it to be pressed, and it went through a bunch of funny nonsense too in that recording process, but someone else paid for it, and there was a big mess. We put it out ourselves, and I remember that it sat there, like there was this big box of CDs, several huge boxes—1000 of them, fuck’s sake, because I remember we pressed 1000.

I was like oh shit, this can’t just sit here. Actually, nobody besides people around here got it for a couple months actually, because I didn’t know what to do with it. I didn’t know anybody, any European this or that, or distribution, anything, so I was like oh my god is this just going to sit here and rot? And I had a friend that worked at a record store, like an underground record store, so I went in there and got every magazine I can, and asked for a list of every underground source that he knew of, everything, and mainstream, whatever, big metal magazines and all that, and I just sent it to everything I could find. Finally a few months later a guy said I want to distribute this in Europe, I had a rate of like 25 copies every couple months, but we did sell all of them within a year, which was actually pretty impressive back then.

So yeah! There was no month it came out in. It kind of came in..

Came into being?

It came into my living room! [Laughs]

It sort of slowly, slowly got rid of copies. But it did catch on, like weirdly, like it caught on, a few people got a hold of it through some magazines that I sent it to, like super underground magazines like Sentinel Steel, which is one that I think the magazine was a mail order and a magazine way back when, ’95/’96, and yeah, once it got to people in Europe and underground people it really started selling a lot, which was very cool and very surprising to me.

Why didn’t you expect it to sell?

Okay, first of all, this is a thing that might surprise people a lot. I didn’t know shit about underground metal back then. I mean, I grew up listening to Saint Vitus, and I knew who Trouble was, and some of the underground bands like that, but I didn’t follow the underground tape trading network or anything like that. I wasn’t in that. I just did a CD and thought oh god, I gotta do something about this. I didn’t think it would sell because we just got it pressed up and how do you sell it? I had no idea how to do that.

We were so badly received in the Bay Area at that time that nobody wanted to hear what we were doing. Everyone hated metal. 1996, Jesus Christ, god-awful time for that kind of thing. We were at a really low point. In fact, we didn’t even have a bass player when we pressed the album, and it came to us in the mail, the whole giant boxes. It was just Greg Haa playing drums and me, and we didn’t have a bass player at the time, we weren’t even hardly a band. I thought that probably Slough Feg was this thing that lasted six years, and then at least we documented it with something I was actually quite happy with, a record I was happy with. We put sort of the greatest hits of the last six years down on tape, and I was like okay cool, at least we have this to document this band.

I didn’t think we were necessarily going to get to do another record, but yeah, it sold to my great surprise and to Greg’s great surprise too.

Were there any advantages to recording with a reduced lineup instead of with more people involved?

Well, we recorded with Justin Phelps on bass, but we didn’t have a bass player soon after. That ended not long after that, and then we had another guy, and that ended, and by the time the thing got pressed we were without a bass player. Three people though? No, we were a three piece for a few years.

When’s the last time you played any of those songs live?

Oh, couple years ago. I think we did “Red Branch” and maybe “Highway Corsair” a few years ago. Not that long ago. We used to play “20th Century Wretch” a lot live, and that’s probably the newest song on that record, that was the one that we had written the most recently when we recorded it, and sounded a little different from the rest of them. But yeah, we wanted to spazz out. It’s a weird thing because I’d had Slough Feg for six years, and oh man, there were so many songs and demos and stuff before that. That was just the ones that would sound good with the lineup we had at the time, which is what we’d wanted to do because we’d done these demos that have since been released on versions of that record that we put out since then, reissues and stuff like that, demos from ’92, ’94, and others.

Those are a lot different sounding than the first album. On the first album we had Chris Haa on guitar for a long time, and the band sounded different, really different, for some of those years. When it was a three piece, it went back to being a lot more doing some of the same material but faster, sort of more crazy. Like we became a three piece I was just playing all of the guitar all the time, it was my tendency to go back to a faster, crazier sound, the way the band was in Pennsylvania, because you know, we’re from Pennsylvania and we played for about six or eight months in Pennsylvania as Slough Feg and then came out with Chris Haa and myself. Those are the only original members that made it out West.

We came out here, and I was getting into singing a lot more. There’s some gigs when I didn’t even play guitar. I don’t know if anybody even knows that. Oh! There was that one video that was on YouTube where I don’t play guitar at all, from way back when. That developed into a different direction from when I just sang for a while, and then I slowly integrated the guitar back in.

The first album of course represents where we were in 1996, but there were all these other versions of the band that had happened before then, and there’s some demos from those periods that sound quite different even when some of the same songs were played on them. The idea of the ’96 first album was just to spazz out, really, to really inject a lot more energy into these songs because we thought that would help us compared to in the past when we’d done some of these same songs and they sounded, not mellow, but they weren’t as fast as they were on the first album where they were totally energetic. You can kinda hear it, too, and some of them are too fast even.

When you look back on that album is there anything that you wish you’d done differently?

Oh god, yes, of course, yeah. I mean, there’s production things, which is kind of silly to think about as different because overall for the time and the place that it was done the production is actually pretty decent. We went into the studio with an engineer we’d never met before, all of that stuff, and we didn’t know what we were doing.

Some weird guy paid for the record, and… no, I don’t regret any of this because he laid down a bunch of money. It was a very strange experience, the way that happened. I don’t want to avoid the question because there are things I would have done differently, like the song “Why Not” is too fast. There’s a million things that I think about in the production, oh I did that, I shouldn’t have done that, I shouldn’t have done that, I used really shitty equipment which was normal for back then, some things are too fast. “The Red Branch” was not mixed, it was a version that was sort of an outtake because the version that we mixed ended up sounding really weak so we used the raw-sounding non-mixed tracks that he had on another tape or whatever, a lot of stuff on there sounds pretty half-assed, but there’s a huge energy to that record.

You know, it’s a total first album. It’s very raw. So generally I’m really, really happy with it, and I was back then too. In fact sometimes I listen to that album, and I mean this, sometimes when I haven’t listened to it for a very long time I’ll put it on and be like, oh my god, why did we do any other records? I said it all on that one record, everything I wanted to say. Sometimes I feel that way. It’s the perfect chronicle of me in my 20s: writing this music and the other guys and the band and the whole environment, what we were trying to do. It is extreme, it’s not extreme metal, but trying to convey this incredible anxiety and dramatic energy that we felt in our 20s, and frustration, it’s all totally there. It’s said in a very theatrical way, and it really did deliver what I was trying to do, but the actual way that it took place is really random and strange.

If you want to hear about it I’ll tell you about that actually.

Go for it!

So, this is really weird, but around that time, around ’95, oh man… we’d been together five years, but it felt like a lot longer. A lot of shit had taken place, a lot of changes and stuff like that, and there were three of us then. Justin Phelps on bass, Greg Haa on drums, and me, and I’d been living in San Francisco for five years. We’d gone through a lot of rejection and a few triumphs here and there, and we’d been around the West Coast playing and stuff, and still, no one wanted to hear metal, really, but whatever. Things were pretty dismal, and we had met several people who tried to “manage” us, just like every young band like that that’s in a big city, especially California, people come around say say, well I’m trying to manage a band, and nobody ever knows what the hell they’re talking about, and it’s always like, what are you going to get out of it? What’s 0% of zero? Or what’s 15% of zero? Whatever the hell you want, it’s just a losing game, at that time especially.

This guy approached me at the laundromat. I had a job through a lot of the ’90s managing this laundry place. It was actually pretty cool; it had a bar attached to it, it was a weird kind of joint. You could do your laundry and then drink beer. Sometimes they had acoustic bands and comedy and stuff like that.

Holy shit!

Yeah, it’s just one of those cool kinds of city places. It was a great job. So, I managed this laundromat so I did a little of dry cleaning and wash and fold, I was washing someone’s underwear or something, and this guy, this weird guy approached me, and it was just like totally random. He didn’t know what he was talking about, but he had money. He said, I just heard you say you were in a band, I just heard you talking to that guy over there. I say, yeahhhhh…

He said, well, yeah, I’m looking to manage bands, or something.

I mean, who the hell would do that? Like, they hear someone at a laundry encounter or whatever going yeah I’m in a band, and OH WOW, I’m trying to break into this business! I mean he had no idea. He was maybe ten years older than me at the time, in his early 30s, and he approached me and gave me his card. It said something like, “Profusion Productions” or some bullshit. He was some guy who was a rich boy or something who inherited some money, and I was like no way, this guy doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about, and I took the card and put it in my pocket and thought yeah right buddy. Because I knew already that people tried to manage bands, do this and do that, and they don’t know what the hell. I got the idea that he had money somehow.

One day I was cleaning my pockets and my backpack or whatever, several weeks later, and I took the card out and went to throw it away. I threw it in the trash and ripped it half, and then I remember walking away, and I was at work, so I was walking out of the guest area in the laundromat place, and went, you know. And I thought a lot about this kind of stuff recently, in my mid 20s, about how you can walk down the street and turn one way instead of the other, and encounter somebody that’d change your life. You know that kind of stuff?

Yeah.

Like forking paths, and how random life can be. And I thought to myself, just because you met that guy, and I really remember this very distinctly, just because I just met that guy and he was full of shit and didn’t know what I was doing… but what if you called him and risked just wasting a little bit of time, and ended up with a record coming out, or by some bizarre chance he did know what he was doing? What the hell?

I took the thing out of the trash, and I looked at it, and a couple of days later I said I’ll call this guy, what’s the worst that can happen? I called him, even though I’d been all this shit, and we’d been through all this bullshit with people telling us they could do this or that for us and sorts of stuff and I felt like I knew way better, but I did it. He’s like, oh yeah you’re that guy from the laundromat, I said yeah, and he said let me come in and talk to you. He came in and talked to me, and started talking to me about wanting to invest in a band and all this stuff, and I talked to him maybe twice, and he said, what I want to do is put you guys in the studio and make a really good recording, and then send you up north to some of the places you play like Seattle and Portland really put money into.

The more he talked to me, the more that I realized, no, he didn’t know what he was talking about. But I thought, he’s going to pay for a record for us to do! What the hell? So I thought that I’d never be able to afford that myself, to really go in and spend time in the studio. Next thing you know he was taking us around to studios, and just saying that we’ll come up with a list of people who might want to record. It was like $2,500, which back then was a hell of a lot of money, especially to me.

He just laid it down, and we were there for a couple weeks recording the first album. He said, well, what I’m going to do is that I’m going to press it up this way, and I’m going to do this, and this, and I was really getting the idea that I knew more about it than he did, but I was like, whatever, let’s do it. So we got it done, and Justin, and Greg, and I, were all like this guy’s kind of a shyster, but whatever, let’s see what he does.

Towards the end of the recording process he got very nervous, which is totally predictable because he’d never done this. He was like, we have to talk about how this money is going to be paid back, we have to talk about blah blah blah. I said I thought he was going to put the record out, and then he started throwing all of these demands down, and all that shit, and I was like, dude, put the record out. He was like, yeah but we have to have a plan now, for you to make this money back. We had a confrontation and after the fact he got nervous about it.

You make a record, you take cassette copies home to listen to back then, not CDs but cassette copies. We had the final mix, we’d finished it, and we had a cassette mix off that digital audio tape, back then that’s how you did it, totally analogue the whole process aside from putting it on digital audio tape. So we had the cassette that was right off the digital audio tape of the master, and by the time we got out of the studio, said to the engineer, okay, so are you going to give us the DAT tape? He said, uhm, you should talk to Kurt, that was the guy’s name, about that. I said why? He said that he told him not to release it to us until something happened, and he was going to take it.

It turned into this thing where he got freaked out and took the master tape, and said that until I get some of this money back, I can’t release this tape. It turned into a total nightmare, which we knew it probably would. And so we ended up having this big conversation with him and he was totally a nightmare. He was like no no no no, I need some of the money now, and I said where the hell am I going to get the money to pay you back for this thing? You said you were going to put a record out. But again, totally predictable and it didn’t surprise us.

We had this big conversation about it, and I said look, we have a cassette tape that’s right off the master DAT tape, let’s just take that somewhere and see if someone can clean it up and put the damn thing out ourselves, and to hell with him.

And so we did.

…

…

[Laughs]

Yeah! It’s like, fuck you buddy!

I took the cassette tape. By this time Justin Phelps, the bass player, was becoming a recording engineer, going to a recording school that happened to be right down the street from the laundromat where I worked and right down the street from where I lived actually too, in the same neighborhood. He was starting to learn how to do recording engineering and was still in the band at this point. He knew this mastering engineering guy who allegedly was very good, very nice and cool, and cheap and all that.

We went to him and said, look, we got the cassette copy, and said he’d try. He ran it through all this stuff and you know what? It sounds fine, it’s right off the DAT, and that’s what we did. We cleaned it up as much as we could and never talked to that guy again. Just never called Kurt again. I thought well he’s going to demand all this money he knows I don’t have, so to hell with it. I dunno if he ever knew we ever put it out or whatever happened to him. We made a master CD probably off the cassette tape then and just pressed up copies, and that was that. Put it out ourselves.

It was a pretty good deal when you think about it [laughs]. A lot of stuff like that happened back then, when it was hard to make a record and you had to go to a recording studio and it cost a lot and all that stuff. I’ve heard a lot of stories like that. Some person who doesn’t know what they’re doing gets all ambitious and freaks out when they end up having to spend a bunch of money. But I’ve been through enough, I’d done enough demos and seen records made, to know that you know what? He thinks that we need that master tape, he doesn’t realize we have cassette copies and that you can make an underground sounding record. Of course it’s a lo-fi sounding record, but it would have been anyway. If we had the DAT tape it would have been a lo-fi record, it was done relatively cheaply. So that’s how it happened. It was a time when you couldn’t just go into your room and make a record, or just download pro-tools and make a good sounding record on your own. You had to have the money to do it.

Do you think there’s any advantage to that? That it used to be that you used to have some rich guy walk into your laundromat to make a record?

[Laughs] Do you mean the fact that you had to have a lot of money or…?

Yeah, a barrier of entry.

Yeah, exactly! No, very good. People don’t usually associate that, they usually think of it like the ’70s or something. “Back in the ’70s or ’60s, if you had a record that meant something, because it was hard to make and not everybody could make a record.” But it was also somewhat, not as true, but it was also true in the ’90s, or at least the early ’90s, up until like ’95 when we met that guy. And yes, I think there is an advantage to it. You have to really want it. You go into a recording studio with an engineer and you feel excited, you feel nervous, it feels like wow, I’m making a record, it’s so special.

I’m sure there’s some advantages to the way it is now. They could go either way with that. They could say, oh, in your own bedroom or your own house you have all the time in the world, there’s no pressure on you, you can make a better record and spend more time on it. But I think that definitely there was an advantage to feeling like it was a very special opportunity to make a record. Back then you know, we had a CD. Not every band had a CD in ’96. I knew tons of bands with tapes but if you actually had a CD, it was like oh, you actually made a CD. That’s the last period when that was a special thing.

I think there is an advantage to it. There was less stuff out there, too. If you actually made something that was on a CD, or, well, nobody was doing vinyl back then or at least not much, but yeah, it was a different time. Things weren’t as saturated. You’d get more excited than you might now.

Did you have any of that feeling of magic as you put out later records, or was it a one time deal?

There wasn’t the feeling of urgency of any of the other records as there was on the first record. The first record was like, this guy has money, he’s putting us into a studio, but he can pull the plug at any second. We don’t know why he’s giving us this money or putting out this album. We don’t know what his motivation is, it’s really weird, it doesn’t make any sense. It was kind of sketchy and teetering and weird from the get go. I remember telling the other guys, Greg and Justin, look: this guy’s offering us money now. In a week he might change his mind and there’s nothing we can do. Let’s get the fuck in there and make this record, and I kept saying that to then—and maybe that’s why it’s so fast… we were just rushing. But there’s an incredible sense of urgency that was also really cool because it represents where we were at the time.

No, never was quite like that again.

What are your last things to say about the album in hindsight, looking back?

I’m glad I got to do it, and it was the gateway to doing more records, though that’s the generic thing to say. I’m pretty happy with it. I guess I’ll say what I’ve always said: sometimes when I put that record on, it never sounds bad nor weird to me. Every time I put it on, I go, oh my god, this says exactly what I wanted to say. I got it out exactly as I intended to. I don’t know if that’s that common with the first record. Obviously there’s flaws on it, but out of all the records I’ve done, I think it’s the one that’s come out the most exactly like how I intended it to. Maybe it’s because we played the songs 1,000 times at shows live and we’d demo’d some of the songs years before that, so they had so much time to ruminate in my head… marinate… whatever the word is.

When I listen to it—I honestly do—I think that if it was the only record I ever put out that would be okay, because it said everything I wanted to say at the time. I’m happy with it.

…