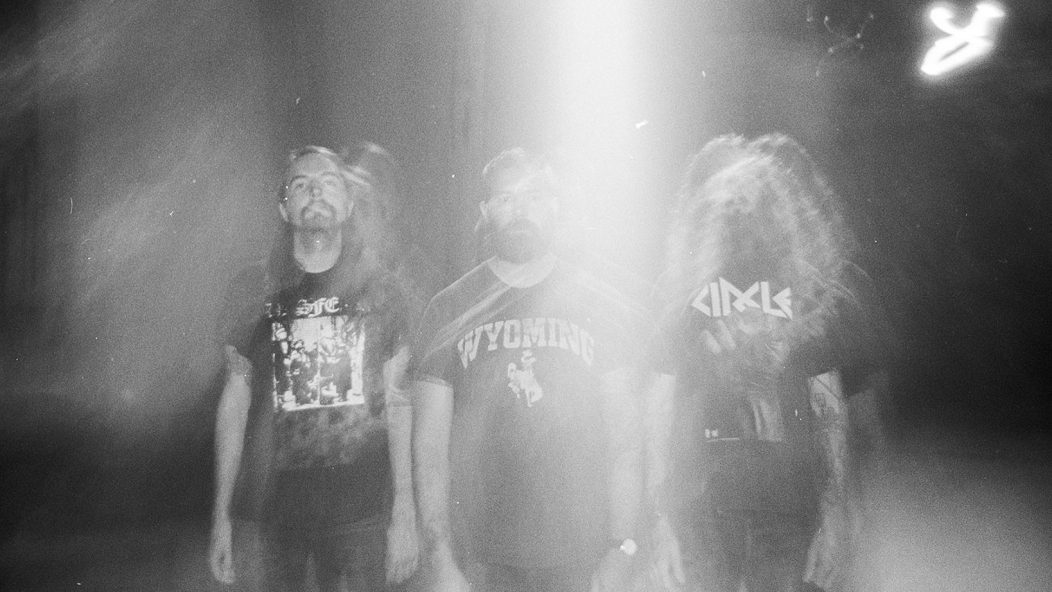

Acute Disruption: A Conversation with Aaron Turner (SUMAC)

Everything is ephemeral — music, art, life, and especially recordings of interviews. My interview with Aaron Turner of experimental trio Sumac very quickly turned into a Sisyphean effort. With a recording of a, to toot my own horn, pretty good interview on my phone which suddenly factory reset before the recording could be uploaded to the cloud, I was suddenly left with nothing. No recording, no interview, just memories of cool things we had discussed.

So, how do we recreate an entire interview? Hell if I know, but Aaron and I ended up talking again and seeing where our conversation went. It went pretty well. This sort of interpretation and recreation ended up being pretty fitting when it comes to Sumac’s latest album, May You Be Held. A largely improvised album centered around heavy, expressionistic, metallic roaring, Sumac dealt with the difficulty of finding exactly how their improvisations would work and… went with it. Each iteration would be different, but the central idea would be the same. Aaron and I tackled this issue in our second conversation, and you will find fragments of comfortable familiarity with ideas, like we had discussed them before, but we ultimately had a very different conversation. Nothing is forever, you cannot perfectly recreate anything. Thus is reality. Read my interview with Aaron Turner below.

May You Be Held is out now on Thrill Jockey.

…

…

So, with this new Sumac album, May You Be Held, we see a larger progression in the Sumac sound. Obviously, improvisation and experimental tactics have been a part of Sumac since The Deal but with this one, there’s a higher concentration on the improvised aspects, I feel. I was curious, from the composition side, how that all came together.

When Sumac first started, I had figured out through the years of being in other bands that playing songs the same way over and over again started to really wear on me. It robbed some of the energy from the songs, and also just from the joy of playing live. So when I was thinking about starting another band, and what I wanted to do differently, I realized that my interest in improvisational music could be an important factor in starting a new band. So I knew that was going to be a necessary component to work into what we were going to do, or what I wanted to do with Sumac. This was before I even had other band members to play with.

So, I knew that going in. I mentioned that to Nick when we first started playing together. His experience as an improviser was pretty limited, so we just kind of had to start integrating improvisation into what we were doing slowly. I think there was [were] maybe two or three parts in The Deal where there’s improvised passages and probably about the same number on What One Becomes, although we stretched it out more on that record. It’s just been kind of a linear progression where the more Nick and I play together, and the more Nick and Brian and I play as a trio, the more comfortable we become with freely improvising. Not just within the structures of our written songs, but also just starting with zero ideas and no parameters whatsoever. So, you know, with this record, yeah, you can hear that there’s more improvisation going on. That was certainly our intent. But it also wasn’t as if, from an inside perspective, we were making a huge leap. It was just kind of taking another step forward on a path that we’d been traveling for a while. And also, as has been mentioned a few times along the way, our working with Keiji Haino on a couple of records and live performances was also very helpful in that it really just pushed us to dive really deeply, and in a very committed way into the process of group improvisation.

When it comes to the art of improvisation, there’s the general idea of feel, but there’s also the idea of the conductor. Maybe not the person who’s guiding it, but the force, so I was curious what guides your improvisational passages?

For me, as an individual component of this group, feeling is always the guide. When I’m playing and I feel that connected energy between myself and my instrument, the resonance of what’s coming out of the amplifier, and also listening to what the other players are doing, I tend to just follow that intuitive path of emotional communication. It’s not always a clear guide, necessarily, however I have often found, especially in cases where we’ve been able to document our improvisation, that the ones that feel the most connective end up being the ones that are the most thorough and complete as pieces of finished music.

There have been instances where, in the moment of playing, what we’re doing felt completely awkward and unnatural and even, well, there’s a level of self-consciousness that I’ve experienced at times where I really question what I’m doing and worry about it and in retrospect I’ll listen to what happened and I’m surprised to hear that something good came even out of those moments of insecurity or self-judgment. So, I don’t know if I can say that there’s one overarching guide, but maybe a good way to summarize it is “trust.” Trusting in the process, trusting in the other people that I’m playing with, that at the very minimum the action of playing in and of itself makes it worth doing. And if something good arises out of it, that’s even better. But I really just think there has to be that initial trust that everyone is going to inhabit the moment as it’s unfolding and do their best to follow whatever path seems to unfold as you all take action together.

Going back to what you were saying about feeling earlier on, in a previous conversation we had, you brought up that Sumac was this expression of feelings. Whether it’s a personal expression or a spiritual expression, etc, which can be tied to the artistic genre of expressionism. Do you feel that Sumac is an expressionistic being?

I mean, I don’t know that I would define it that way necessarily because I think almost all acts of creation are obviously an expression in some form or another. We are very deliberate in our practice of digging in deeply into ourselves as individuals and also as a collective unit. The more thorough our practice is in that way, and the deeper we are willing to go, and the more vulnerable we allow ourselves to be, the better the music becomes. Beyond mental and spiritual, I would say there’s also a heavy physical component to it as well. I think the use of my body as part of what we’re doing is really important. That physical aspect of playing is very important both in terms of how the music sounds and in terms of how it comes across live. That’s what also drew me to playing with Nick. He’s a very physically expressive player and I think that especially when it comes to drums, that’s super important with the type of music we’re doing. I value technique and ideas to some extent, I think that willingness to put yourself on the line physically is very important.

I don’t disparage anyone who approaches music from a more intellectual perspective, including in the realm of composition, but for me, I cannot write something based around the idea that it needs to be a certain way. I can’t write something in a certain key because I think that the music needs to be in that key. I can’t just approach it from a technical or analytical viewpoint, it really has to be coming from that place of deeper intuition, emotionality, and physicality. The moments for me that have been the most rewarding, in writing, recording, and in playing live have been those moments where I feel like there is the very visceral and very interconnected exchange between emotional, spiritual, and physical aspects of playing.

You certainly hear the physical aspect of the music, which is interesting on an album which, when you take in music without a visual cue, is largely cerebral, with the occasional visceral reaction. I was curious as to how you went about expressing this kind of physical music in this album?

Part of it is playing loud. I don’t think that we play loud for the sake of it. I’m not really interested in volume wars. We haven’t striven to be the loudest band possible. At the same time, I think there is a degree of richness that comes out in the music when it is played at a loud enough volume that it can be felt physically. Also, in terms of my instrument specifically, feedback is a very important component of playing and that can obviously only occur at increased volumes. It’s not an engineer’s dream for a band to just be playing as loud as they can, but we play just about as loud in the studio as we do live. I think that feeling our instruments physically has to be part of the process.

There is a degree of removal in the recording process from the deeper experience of playing in that you’re in a studio, you’re often wearing headphones. Sometimes the amplifiers are in isolated spaces so that they’re not bleeding into the drums, so that does make it less natural. As such, I personally don’t feel like it is quite the same visceral experience that it can be live. At the same time, we try to record as much as we can, for Sumac stuff, live. We don’t do a lot of overdubs. We don’t re-track a lot of things. I think that keeping as much as we can of the initial spontaneous performances helps retain that very physical live energy.

Again, specifically just referring to what I do, when I record vocals I do them all on my own in my home studio. Having that privacy allows me to just really unleash in whatever way I feel is necessary to get the best possible vocal performance, so it ends up being a really physical experience for me. I feel I really push myself physically, partly because that helps me feel connected to the performance itself and really allows me to tap into the music and also because I want that physicality and that level of extremity, in a sense, to be part of the recording. Again, a lot of what I do is not based around technique, in fact when it comes to vocals I’m sure my technique is awful, in terms of what is considered proper. But at the same time, that’s just the way it has to be in order for the music to sound the way that it needs to sound.

When I listened to May You Be Held for the first time, I think I messaged you and said that my head was being bashed in. I definitely, with the physical aspect of the music, I in turn reacted physically. You know, I moved around, I made a fist. What would you think is the proper reaction to this kind of music if there is one?

Yeah, that’s great. I mean, whenever I put on a record that I feel really excited about I tend to respond physically as well. For certain things that don’t make sense, you know. I’m not going to be dancing around with my child while listening to an ambient record, even if I’m really enjoying it. But if it’s something that’s rhythmic and has a really propulsive energy to it, I feel naturally inclined to respond physically. It might not necessarily be dancing, but I just, head nodding or, I don’t know. I think there’s an innate human desire to move our bodies in accordance with music, and probably a lot of very early forms of music were largely rhythmic and our bodies responded in tandem to that. And I want people to be moved by this music on all levels, so if that happens for people in their cars or their homes, with their headphones wherever they happen to be, then that’s great. I consider that a great compliment or a great response to what we are trying to do with the recordings.

When we had discussed the album last, we had talked about the title, May You Be Held. It possesses a different kind of meaning now, so I was curious about the title, what it means and how it came to be.

I thought about this a lot, and I’ve really been trying to simplify my answer because this has come up in a few interviews. I can say it this way now, I think. My greatest wish for myself and my son, for my family, for humanity as a whole, is to be able to experience a foundation of love that allows people to move in the world and to be connected to one another in a way that is more in accordance with what I see as the foundation of life. I think that humans are certainly destructive, in some ways, and part of that may be instinctual. However, I think a lot of destructive tendencies have come more out of the process of being indoctrinated by our cultures. And not just our present culture, but our culture historically. I don’t think that that is the base, underlying component of human reality. I think that humans are social animals. We need to be loved and we need to love. The fundamental aspect of Sumac’s music has been about an expression of our love for life and the preciousness of the life force. A joyous ritual and expression of life. So, I’ve written about that in a lot of different ways across all of our records. I’ve also written about quite a lot of things that I feel sort of, the disruptive factors that prevent us from loving ourselves truly and prevent us from loving other people and how those things come to be. What is necessary in order to dismantle those things. A lot of the music and a lot of the lyrical matter can come off as being dark and turbulent, and I think that’s a necessary component of getting to the underlying thing, which is this human desire to survive, to connect, to love and to thrive. The record was written during what was already a tumultuous time and now it’s being released during an even more tumultuous time. I was able to think more about the lyrics and the song titles and the presentation after the shutdown had already begun.

So being in that place of isolation and also working at parenting my child every day and working at being a partner to my wife on a daily basis, that very intimate process of domestic life coupled with my desire to engage with the wider world and what’s going on just led me back to these very fundamental themes about really wanting to make music that allows people to connect with these very deep and vulnerable, and in some ways very primitive, needs. It’s a hard thing to write about. I feel like it’s a very big subject and I don’t always feel like I’m equipped to handle it on an intellectual level. I know what I want it to be and I know how it feels when I’m inhabiting the music, but in terms of how I present it and how I go about writing it out in words is a much bigger struggle for me. I feel like that is part of the reason why I keep returning to these themes, because they are so complex and they are rich for me because it requires personal exploration and it requires that struggle of trying to understand what it is I want to get across and also trying to understand myself because in some ways I don’t and I think that that’s also part of the human condition is that we can’t ever fully know ourselves. So this music is, in a way, a process of trying to at least map out some of the dark areas and that process in itself is difficult at times. Sometimes I just want to create a container of love around myself, around the people I’m playing with, for the people who are hearing the music, for humanity in general so that we can dive into all these difficult things and come out better on the other side. That sounds grandiose and it sounds to me like an awful lot to ask from a record or from a band, but I also feel like it’s very worth trying to do these things otherwise it just ends up being trivial.

The discussion of love and a zeal for life is something that you saw in a lot of primitive, proto-metallic stuff. Led Zeppelin, etc, where there was this sort of celebration. From the way you describe Sumac, is that you have a zeal for life that you want to express in the most intense way possible. I was curious, as an extreme metal band, what is it like for you expressing this message of love and compassion?

What I was alluding to in my last answer, I think the spectrum of human experience is obviously very wide and we tend to compartmentalize our experiences within these very narrow parameters. Any work that’s done on a personal level, oreven on a personological level, reveals that there’s a lot of fluidity between our experiences and our emotions and our cultures and subcultures. So metal can be largely summarized as being angry music, but for me I think that is a very monochromatic view of what it actually is. I think metal music, and our music, expresses a very wide range of emotions and experiences. There’s also just kind of the pop culture reading of love through music, which often manifests in a one-dimensional way. It’s either songs about physical conquest and lust, about the victim of love, the person who’s been dumped or who has this unrequited love, or it’s kinda like this sappy, romantic notion of love where it’s essentially the musical equivalent of a Hallmark card. All of those readings tend to be very limited, and for me are not reflective of my own experience of what love has meant in my life. Loving relationships are often full of a lot of different things: upset, conflict, compassion, lust, heartbreak, connection. To really fully engage with what is a very complex topic, I feel like all of those things need to be explored.

On another level, I also am just trying to dismantle the idea of what certain aesthetic signifiers are supposed to be. Sonically heavy musical textures are often just looked at as signifiers of violence or anger. But I mean if you look at nature, for instance, a rainstorm is a beautiful thing. Of course it can be destructive, but it’s also incredibly beautiful. The ocean can be seen as this very beautiful thing and it also has so many destructive possibilities inherent in its very nature, so I think there’s been a lot of classification about what aesthetic signifiers mean in music that in some ways is necessary because people are trying to articulate what they’re hearing and they’re trying to put sounds into words, it’s inherently a complicated translational process and also a subjective one. But for me, again, this idea that metal is always just this one-dimensional angry music is very limiting. It’s very limiting for me as a person who makes this music to think that what I am doing, that what we are doing as a group, is only representative of rage and anger. That is a component of it, but that is certainly not the totality of it.

We are very positive people. I don’t mean happy people, because in many ways we’re not, but I think we’re very positive people and the reason we play music is because it brings us joy. Again, I don’t think joy needs to sound like major chords. It doesn’t have to imply any certain tempo. It can be expressed in whatever way feels natural to the people who are making it. It just so happens that what we make as a group incorporates a lot of dissonance, a lot of chaotic elements, a lot of textures that can be sonically harsh, but that is not purely coming from a place of anger. I think in many ways it’s the opposite a lot of the time. So, again, that’s maybe a tall order to set for ourselves, to dismantle the idea of what musical signifiers have meant throughout the years, but that’s up to a lot of people who play music that loosely falls under the umbrella of heavy metal. I know that many of them don’t feel like their musical is hateful or coming solely from a place of rage, or purely about having a cathartic outlet for their pent-up anger. Again, that is a component of it, there’s no denying it but that should not be the sole purpose for doing this and I realize that more and more as I’ve gotten older. I have always felt that way and now I feel compelled to make that an important aspect of the presentation of what we’re doing.

To contextualize the existence of Sumac a bit more, even when we started, that was a goal for me. As we have gone on as a band, that has become more and more important. We’re now in an era in our country where divisions between people and the clashes that are arising out of those divisions are becoming really significant and very visible. Of course the underlying factors that have brought this up have always been there. At the same time, I feel more and more compelled as an artist to try to make music that offers the possibility of unification and offers the possibility of increased empathetic awareness of other people’s humanity. Sometimes you need to make music that just destroys people’s conscious fore-brain to get to that deeper level basic human feeling in order to understand that that feeling is shared by everyone. So, there is a necessary component of violence or maybe just like a very pronounced physical attack on the senses that needs to happen in order to break through that kind of surface-level conscious static and allow us all to reach into the deeper stuff that is essentially, on a core level, universal.

So we’re talking about dismantling a lot of things. There’s an artistic aesthetic, emotional aesthetics, there’s dismantling the traditional idea of positive love and instead it being something more complex and interesting. What else does Sumac want to dismantle? Is there anything else?

[Laughs]

I’m asking that genuinely, not sarcastically.

No, I get it! I think we are constantly trying to dismantle our own limits as players. We’re very consciously trying to push ourselves to the very edge of our abilities so that we can progress. In order to do that, we need to put ourselves in a place where we’re not always able to actually play our own music. [laughs] That means writing parts that are hard to play sometimes. It means embracing improvising and the willingness to fail that comes along with that. It means playing faster or slower than we’re comfortable with a lot of the time. All of that really allows each of us to move beyond where we have been up to that moment, so it’s really about a desire for dismantling our own artistic boundaries. Also, I think, talking about composition versus improvisation, I think the willingness to destroy a musical composition through the act of completely and intentionally causing it to fall apart has been a very rich area of exploration for us as well. We have these fairly meticulously composed sections that then dissolve or expand outwards into things that are much less clearly defined in terms of their structure. That juxtaposition of form and formlessness I think is very interesting. Part of that stems from a lesson I learned in high school from a great art teacher I had. He was kinda the reason I even stayed in high school. He inspired me in a lot of ways, but he saw what I was doing with my drawing and painting and he encouraged me and he also encouraged me in very specific terms to not be precious with my artwork.

To look at something that I’ve made and maybe I’m even satisfied with, and to be willing to completely destroy it in order to move past that safety zone where you know you’ve done something that you’re good at, but maybe you need to be able to just really blow that apart in order to progress. I’ve tried to keep that mentality throughout all of my various creative endeavors since then. Very often, if I feel like I’m getting too constricted around a certain idea, whether it be a piece of art or a song, I really sometimes just try to metaphorically throw it in the blender and let it get chopped up and see what happens once all the pieces are reconfigured in an unfamiliar way.

We see that a lot in your music, especially in the trajectory that you’ve taken. I think about your collaborations with Keiji Haino and how that completely turned Sumac on its head. Do you see yourself turning the band on its head in a more consistent fashion? Is that what you strive to do, or is there a plan in place?

Yes. Again, that’s been part of the intention from the beginning. However, in the beginning, there needed to be at least some familiar parameters set that we could all work within in order to have a springboard to jump from into lesser known territories. But I did, the other day, an artist to artist interview with my friend Tashi Dorji, who has also toured with Sumac. We were talking about each other’s recordings and he said part of the thing he liked about the Keiji Haino recordings was it sounds like Sumac basically got splattered all over a room by Keiji Haino. I thought that that was a perfect description and it also linked up with something that came out of a discussion that we had with Haino last year. We were gonna play a show in Vancouver with him and we wanted to talk before the show. We met a couple days before the show just to have a conversation. Through the course of the conversation we talked about one of our previous performances together in Tokyo and he admitted that he had purposely laid musical traps for us to try to fuck us up. Part of his intention in doing that was to break down our identities. I thought that that was a really… I had felt that “in the moment” and not necessarily known how to process or articulate it afterwards, so when he said that I really was moved by that idea. The process of being a musician and being a public performer often means putting yourself out there and in some ways purposely cultivating a persona. Sometimes that extends into the way that I approach my instrument, or that anyone may approach their instrument when they do their thing. Whether it’s conscious or unconscious, that does become part of the process where you’re doing the thing that you develop and you feel comfortable with. That can become a trap. So, in order to escape that trap, sometimes there needs to be elements that are purposely tripping you up (I’m going to change this back to the first person).

There need to be things that trip me up. There need to be things that fuck with me. There needs to be something that is purposely and acutely disrupting what I am trying to do because sometimes if I am too deep within my own train of thought, that doesn’t allow for outside influence to come in and change the direction of my thought and I really feel that playing with other people is allowing those channels between people to open up, and by doing that, you’re connecting with people in a way that you’re not able to otherwise. Not only are you connecting, but by opening up that pathway, you’re allowing energy and ideas to pass through you and pass back and forth. And that is the way in which I have experienced the greatest transformations as a player. I want to invest in myself and I want to present something of myself that feels authentic, and also I want to be connected to and open to these channels that allow my musical DNA and my personally developed aesthetic to change and to grow. The idea that there’s this sealed vacuum of creative energy that people possess is largely unrealistic, with very few exceptions. There’s certainly some creative geniuses that have come from their own world and been largely untouched by anyone else’s, but for the most part we are a product of our world and of our connection to other people. So we might have a personal filter that allows things to take shape in a certain way and I think it’s great that people’s personal selves are evident in what they create. At the same time I’m also interested in how those selves can change by being necessarily connected as part of the larger world.

I’m trying to figure out how to follow that up, that was really good. Our call has officially gone on longer than our last, so we’re treading into some interesting territory. I guess I’ll leave the floor open to you if there’s anything you want to talk about.

Um, I don’t know. As I said earlier in the conversation, I think that our music has a lot of pretty grand intentions and I don’t believe that we are a vehicle for change on a really massive scale. At the same time, I think there is a pervasive atmosphere of nihilism that has crept into a lot of music that I have encountered in the last five, ten years. I understand that this is a time when people are overwhelmed and I understand that there are a lot of factors that are making people feel discouraged and I, myself, at the end of some days am very discouraged and I’m worried for my son’s future, to put it in a very selfish and personally specific way. At the same time, I believe that art and the collective practice of making art has the potential to really galvanize people’s spirits. I think it has the potential to act, at least in part, as a component of social change. I think that the stuff that has affected me the most profoundly has gone beyond serving the need to entertain and acting as a transformational tool. I very much hope, and have very much intentionally injected, these kinds of ideals into our music. I want this music to touch people and I feel really strongly about this record, maybe more so than a lot of the records I’ve made throughout my whole career as a musician.

All I can say is that I hope that people who are feeling discouraged can find something hopeful through the process of listening to this record and also that people who are making music can think about what they have to offer people in that way. I’m not saying that everybody needs to be making music that’s about the hope for change or the potential for change, or about holding onto hope for humanity. What I am saying is that music, I believe, arose out of people’s desire to celebrate life and to understand life and to even engage with what’s beyond their comprehension. I think that to be an artist right now, in this moment, offers the chance to really serve that purpose again. As much as people need something right now to chill out, or to relax, or even to check out, I think more importantly people need something that is going to engage them with the world and engage them with other people. Take them to uncomfortable places that they need to go in order to be able to move through all of this shit. So, that’s a lot to put on music, but I don’t think that it is outside of the realm of what music and great art is capable of. I don’t know that we have achieved that, I wouldn’t begin to presume that we have, all I can say is that this is my hope for the music, that this is where we are coming from as a group, and that is what I really enjoy hearing in other people’s music. There’s some music that I enjoy that’s full of despair and full of rage, and I’m not just talking about metal music, I’m hearing this all over the place. I think that being willing to express that hopelessness and despair is a part of being able to handle it. We need to externalize the shit that we’re feeling, that feels too much to bear, in order to be able to carry on. So, again, this goes back to the complexity of expression and what it means to try to engage on a deep level, to express what we want to express in a natural way but also to do it with the intention that it serves a greater purpose.

…

Transcription by Ben Handelman.

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.