"Stained Class": Judas Priest's Quantum Leap

…

“Who are your biggest influences?”

It might be the most reviled question that an artist can be asked during an interview, but it’s an inquiry that more than makes sense from the curious fan’s perspective. As dedicated, cognizant, and voracious music listeners, it’s impossible not to draw the lines of development between our favorite artists. From Robert Johnson to Eric Clapton to Eddie Van Halen to Dimebag Darrell: it’s only one of the endless examples that can be used to trace out the history of the music we love. It adds much-needed context to bands and albums we hold dear, and it’s simply fun to do.

Though no well-intended artist knowingly apes their predecessors in the pursuit of their own creative accomplishments, the lines of influence are sometimes all too obvious. There are at least thousands of kids that heard Dave Lombardo’s break in “Angel of Death” and were inspired to add a second kick drum to their set, or hell, pick up a kit at all. And in turn, the first time a 13-year-old Kerry King heard Judas Priest’s “Dissident Aggressor,” he heard the guitar solo that he would play for nearly his entire career in Slayer.

Up through the 1800s, the way the universe worked was explained through a similarly easy-to-trace manner. That thinking is now known as classical physics. Objects, including light and sound, behave like waves, ebbing and flowing with variable frequency. Classical physics explains most of the phenomena we can observe with our senses. It’s convenient and relatively easy to understand.

By the dawn of the 20th Century, Max Planck and Albert Einstein found that classical physics failed when placed under the microscope. To make the math reconcile, the two abandoned conventional wisdom and changed the way they perceived the universe. They imagined light not as a wave but as a particle: a discrete packet of energy. Their work pioneered the field of quantum mechanics. It’s a world of understanding that allows us to break down matter into trillions upon trillions of atoms and their subatomic particles. For a theory so focused on hard-line discretization, quantum mechanics requires some rather abstract thinking. To our limited senses, the world behaves like a wave. We can’t immediately see the universe quantized before our very eyes.

It’s easy to digest music history as a wave operating under the principles of classical physics. For the most part, we can follow influence from artist to artist with little difficulty. The closer we look however, the easier it becomes to see the markers of division. We find actual quantum leaps: points in time where the masters independently synthesized something novel and discretely advanced their genre from one level to another.

Within heavy metal, we can point to Birmingham, England, as a setting for some of those jumps forward. In 1970, Tony Iommi reimagined the flat fifth interval with the hellish trill heard in Black Sabbath’s self-titled song. It drew a clear line between “occult rock” and what later became known as heavy metal, repurposing the interval not as a marker of bluesy guitar playing but as a harbinger of doom. Of course, we now know that Iommi’s volcanic riffs aren’t the sole defining trait of heavy metal. Speed, aggression, attitude, and boiling-hot virtuosity are now just as associated with the genre as Iommi’s flat fifth and thunderous chords.

This is where Judas Priest, Black Sabbath’s one-time Brummie peers, come in. In the early to middle 1970s, they found themselves in a similar state as their peers Deep Purple, Thin Lizzy, and Led Zeppelin: pushing against the furthest edges of rock, but failing to fully crossover into the new sound. The future Metal Gods were metallic, but they were not yet metal. It took four records and nearly a decade in the music business, but by 1978, Judas Priest had finally finished the job that Black Sabbath had started. Forty years ago they released Stained Class. With that record, Judas Priest made heavy metal’s final evident quantum leap and finished writing the definition of the genre.

Their earlier records introduced some of the tropes that now litter the sound. On “Tyrant” from Sad Wings of Destiny, Glenn Tipton and K.K. Downing’s rapid palm-muted chugging and harmonized solo gazed onward at thrash and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Their reimagined cover of “Diamonds and Rust” by Joan Baez, featured on Sin After Sin in 1977, showcased the galloping guitar pattern that gave Steve Harris rhythmic fuel for Iron Maiden songs throughout the decades. But on these initial releases, Judas Priest were still very much operating within the confines and paradigms of rock music.

“I think it was still very much rock, you know,” founding member and former guitarist K.K. Downing says. “We were kind of a bit north of rock really because obviously, having lived and experienced the evolution of music as we know it today, from blues to progressive blues to rock, hard rock, heavy rock… we were a heavy rock band because we were not south of rock, we were north of rock. That’s kind of the way I kind of made the identification. And then, obviously, heavy rock, then came heavy metal, then thrash metal, death metal, speed metal, and so it goes on.”

By the time of Sin After Sin’s release in April 1977, Judas Priest were in need of a drummer. Thanks to the help of Roger Glover, bassist for Deep Purple and producer of Sin After Sin, the band found Les Binks. Already a seasoned session musician by the time he joined Judas Priest, Binks offered the versatility and technical ability necessary to propel them toward being a full-fledged heavy metal band.

“I grew up with kind of the same influences as the other guys,” Binks explains. “And so I listened to, obviously, Cream with Ginger Baker and Eric Clapton, and all that sort of stuff, and also Deep Purple. I really liked Ian [Paice]’s approach to playing the drums, and also, of course, [John] Bonham with Led Zeppelin. But none of those bands were really, sort of, what you would’ve called… they certainly didn’t call themselves heavy metal bands in those days. And, I mean, they were just hard rock bands.

“And I think it wasn’t until Sabbath came along that they really sort of put the stamp on it as heavy metal,” Binks acknowledges. “And even the early Priest stuff couldn’t really be categorized as heavy metal. They sort of developed into that and they sort of found their way towards that with the fourth and fifth albums, the ones that I got involved with.”

Downing adds: “We just came out of the studio, working with Simon Phillips, who was a stand-in to do the [Sin After Sin] album because Simon was such a whiz kid, such a really good drummer. We did ask Simon actually if he would consider going out on tour with us, but he declined because he was kind of pretty young.

“So I think it might have Roger Glover, who had worked with Les Binks before, that might have suggested Les. And so we gave Les a tryout. And, lo and behold, we couldn’t believe it. He was obviously extremely confident and could do everything that was required and certainly was very able to copy what Simon had done in the album.”

With Binks now manning the throne, Judas Priest made their way touring across the world, playing to audiences that didn’t know what to make of this new lineup’s sound. Unlike their prior jaunts, Priest now had a drummer that delighted in adding in rapid double kicks to older material and playing their songs at warp speed. This was the first iteration of Priest that tackled the United States, supporting REO Speedwagon and Foreigner on a nationwide tour. Audiences varied wildly depending on the territory. For a band dangerously blurring the lines between hard rock and heavy metal, this inconsistency only made sense to Downing.

“Back in the day, in the 1970s, in the 1980s, everything revolved around radio, radio, radio. And so Judas Priest had some strongholds around America, serious strongholds, where the radio stations were playing our music a lot. The audience reaction when we were headlining our small gigs was fantastic you know,” Downing claims. “But when we would play with REO Speedwagon, and Foghat, and Foreigner and bands like that, I guess we’d have probably, 8,000 or 10,000 Foreigner fans in the audience which is kind of not ideal, not exactly. It was kind of a bit of a shock I think, kind of a bit like Judas Priest later on going on tour with Slayer as support, that type of vibe.”

The dichotomy between Judas Priest — who were quickly coming into their own as a prototypical metal band — and their AOR tourmates was not lost on Binks either. “REO Speedwagon, Foreigner, all that, they were playing very melodic, softer type of rock that was FM radio friendly for American radio. And, well, Priest were a lot more raw than that and a lot heavier, and, you know, the double bass drum stuff, the fast and furious,” he says. “So when we went onstage with those guys we really stood out like a sore thumb, because the other bands weren’t doing anything like that.”

“One day, we would play in a little club in Washington, D.C. somewhere to 300 to 400 people and the next day we would be asked to play Oakland Coliseum with Led Zeppelin,” Downing remembers. Binks draws similar conclusions of the time. “That’s the thing about America. You can be really big in one area and totally unknown in another,” he explains. “And every state is different, and they have different laws in each different state, different drinking laws. You have to be either 18 in one state, or 21 in another state, so it was like a whole lot of small, little countries all stuck together.”

Judas Priest had crossed the pond for the very first time, and now their next record was waiting in the wings. Stained Class came to life with similar ease as their earlier records, but the end result wasn’t hard rock, heavy rock, or north of rock. It was Judas Priest’s high dive into pure heavy metal, and the final record that specified the genre’s parameters. Stained Class presented a nearly orthogonal version of the sound that Tony Iommi had offered eight years prior. Metal could no longer be defined only by Black Sabbath’s lumbering sludge, Led Zeppelin’s bluesy romps, or Deep Purple’s classically-inspired flights. On Stained Class, Judas Priest envisioned heavy metal as a sound that was all at once up-tempo, blistering, over-the-top, compact, and downright shredding.

It took an intense and intentional departure from their musical roots to do it, a concerted effort to abandon the blues for good and synthesize a new sound divorced from rock. Even with that effort in mind, the classic fear of stealing music and melodies from his heroes was something that Downing tried to mitigate, even in the days before heavy metal was fully defined.

“I was always aware and I was always afraid that I might be influenced by what someone else had done. You know, songs that were in my head by other bands,” Downing admits. “So I literally, a lot of times, just try and make my mind just go vacant and just let my hands take over to guarantee working on something that was completely original. And back in the day, I think it’s fair to say, as hard as it was to become successful in a band — and it was hard work being in the music business actually writing material — I think it’s fair to say there was an awful lot of great guitar riffs that hadn’t been written at that point. So there’s much more of an encyclopedia without anything written on pages, if you know what I mean. It was just kind of filling the gaps.”

That quest for originality was something that dogged endless bands throughout the 1970s. No matter how long they made their songs, how low they detuned their guitars, or how high Ian Gillan could scream, so many players slammed their heads against the blues-rock wall. Jimi Hendrix, while certainly not a heavy metal artist, had given Downing and Tipton the inspiration to try something new and to break the molds that had bound their musical peers in the UK. Hendrix was a rock artist, but his penchant for exploring outside the blues confines had convinced Judas Priest’s riff-smiths to do the same. They weren’t drawing influence from Hendrix’s sound, but rather his fearless and boundless attitude towards writing. That was what ultimately allowed Downing and Tipton to smash through the blues and rock boundaries on Stained Class.

“England was full of great blues bands, white blues bands, obviously. Rory Gallagher, Taste, Ten Years After, Free, there were so many bands,” Downing remembers. “But I think that I wasn’t a blues player and I didn’t want to be a blues player. I think that as far as I was concerned, there was a lot of that about, and it wasn’t what I wanted to do anyway. And when I first heard the great Jimi Hendrix do things more riff-orientated, like obviously ‘Purple Haze’ and ‘Foxy Lady’ and stuff like that, it had a heaviness and an attitude. It wasn’t blues, it was something different. And that’s what I liked and it stayed with me because then, you could then start to write songs that weren’t predictable.”

…

…

“Blues and traditional, as many variations of it as there are, 12-bar blues songs — they’re essentially 12-bar blues — and there’s a kind of predictability about them,” Downing explains. “As much as I love them you know, don’t get me wrong, I liked the idea of composing songs and you are never sure of where it would take you next. To me, it was a darkness, a mysteriousness, a heaviness, an attitude that was to me, to be able to create these audio landscapes. That was something that I really, really liked and some good moments in Priest days that we’ve done songs like ‘Blood Red Skies’ and lots of stuff that we’ve done, without being blues, without being rock, but being something that is I think altogether more musically artistic to be fair.”

Downing and his bandmates embraced the unknown — and brought technical chops to spare — on their journey into the darkness. With that pioneering attitude and instrumental ability on par with their ambition, Judas Priest could fill the aural gaps that Black Sabbath had left open. “Exciter,” the opening track to Stained Class, could have done the job nearly on its own. Binks starts the song with his drum solo, a stark display of his double-kick skill and a sheer declaration of speed. He pumps the gas with an early prototype for the d-beat during the verses and fires double bass machine-gun assaults throughout the choruses and guitar solos. All the while, Tipton and Downing have chiseled and simplified their riffing into an endless stream of notes, a high-pressure pulse that now denotes the heaviness, hypnotism, and relentlessness associated with so many high-octane metal subgenres. Rob Halford focused his expansive vocal range into a monolithic, blood-curdling screech for “Exciter,” and with that, the archetype for speed metal, thrash metal, and the NWOBHM was born. It was a songwriting formula so good, Priest themselves practically repeated it on “Painkiller” over a decade later.

“One of my favorite drummers in the rock scene was Ian Paice from Deep Purple, and Ian was a single bass drum player. But when they made the Fireball album, on the track itself, “Fireball,” he used a second bass drum on it. And it opens up with a double bass drum pattern, and I really was impressed with that,” Binks remembers. “I thought it was a great track anyway, so I thought, ‘Let’s try and do something along those lines with a fast double bass drum thing all the way through.’ At this sound check I was just jamming about and I came up with that pattern. Just came off the top of my head. And I thought nothing of it at the time, but Glenn’s ears picked up when he heard me play that and he said, ‘Okay, can you play that again, Les?’ And so I did, and then he joined in with a guitar riff. That was the start of ‘Exciter.’”

…

…

The drum intro to “Exciter” may be the most obvious way that fans remember Les Binks, but he also brought talent to the band that was more subtle. He wasn’t simply a technical and chameleon-like drummer, but also a proficient guitar player. It was one of the many skills he picked up from his days in the studio as a session player in London. Melodic sensibility, songwriting chops and a high-level perspective of albums were among the implements in the toolbox that he brought to Judas Priest, who at first were simply looking for a drummer to play Simon Phillips’ parts.

“I never really took guitar playing seriously. I always thought, you know, ‘I’m a drummer and that’s what I wanna do.’ But I thought it was a good tool when it comes to writing stuff, because I think every drummer should learn to play a melodic instrument as well. Because, you know, then you learn about melody, chord structures, and all that kinda stuff,” Bink explains. “When you’re entering studio sessions, it’s quite often you’re given a piece of music, and it might be just as simplistic as a chord sheet to follow. So if you can understand all that it helps, every little bit helps. And when it came to doing the Stained Class album, we started rehearsing all the songs for that. I came away from it all and I thought, ‘There’s something missing.’”

That “something missing” was “Beyond the Realms of Death,” the only song from Stained Class that Judas Priest continues to play live to this day. Priest had dabbled with ballads before, but this song featured a focus and weight unlike what they had attempted before. They had found a way to counterpoint staccato high-gain riffing against sparkling acoustic lead melodies, used quiet-loud dynamics to add punch and emphasis to the swinging hammer choruses and featured leads from Tipton and Downing that were lyrical and made sense within the arrangement. Tipton’s screaming legato phrasing provided a backdrop for the narrator’s emotional crisis while Downing’s closing solo, wah-drenched and bloodshot against a double-time Binks, denoted the morbid climax.

…

…

“All the songs were fairly uptempo and I thought, ‘Well, what we need is a big, big heavy rock ballad that starts off gently with acoustic guitar and then builds up to a big, sort of, heavy riff section to create a bit of light and shade,’” Binks recalls. “So I went home and I just picked up an acoustic guitar, and I had a Revox. That was just a reel-to-reel machine which you could bounce tracks back and forth on, but it was a professional standard machine and a lot of musicians owned them in those days. I just set up a little beat box and came up with the opening chords and the riffy sections and made a little home demo of it. And I had a friend at the time, he was living quite near to where I was in West London, and his name’s Steve Mann. Steve is a fantastic guitar player and works with the Michael Schenker Group, as well as a band called Lionheart that I spent a little bit of time with as well.

“And so I invited him around, and he played the guitar solo on the demo. Then I took it along to the next rehearsal that we had, and I said, ‘Look, guys, I’ve got this song but I haven’t written any lyrics for it. I think I’ll leave that to Rob,’ because his style of lyric writing is very, very his, and it’s very Judas Priest.” Binks — a right-handed individual who played the guitar left-handed — continues, “I played the song to them and I picked up one of their guitars and turned it upside down and showed them the chords, as they were. And they were looking at me in a funny way because they were trying to figure out the chord shapes because when you’re looking upside down at somebody playing a right-handed guitar, it looks a bit weird.”

For decades, Stained Class marked Halford’s final foray into morose, death-obsessed lyrical territory. With the release of Killing Machine only months later, his words shifted toward innuendo, fantastic imagery, and the positivity of metal itself. But on Stained Class, Halford focused on the failings of humanity with a pessimistic and laser-like focus. He condemned Native American genocide in “Savage,” took an empathetic yet saddened view of suicide in “Beyond the Realms of Death,” and mourned Tipton and Downing’s beloved Jimi Hendrix in “Heroes End.” It made for Judas Priest’s darkest record to this day, one entirely devoid of good times and fun.

“With songs like ‘Heroes End,’ obviously ‘Beyond the Realms of Death,’ ‘Saints in Hell,’ ‘Savage,’ it’s all pretty mean stuff really,” Downing remarks. “The whole album to me, as K.K. Downing in Judas Priest, it’s what I really do like and love. And I guess that’s why it’s pretty special to me, because it has that darkness about it. When I think about the early days of Priest, the hallmarks are there really, particularly all of those early albums have a mood. And it’s the fact that we were guys coming from pretty poor backgrounds and it was really a style of music for — just like the black blues artists — music that was created that they could draw solace and comfort from in times of misery.”

Though fame and fortune was just on the horizon, Priest were still a band of humble means. Halford and his bandmates had little reason to write songs that were triumphant or positive then. “Judas Priest in those early days, I mean we were happy at the fact that we were in a band and we were able to make music, but the rest of our lives was pretty shitty really to be fair, because we were pretty poor off,” Downing explains. “I mean, I didn’t have a car until 1979, and that was when I had in the first 50 pounds to buy a piece of shit really, but that’s a car. And so, during Rocka Rolla, Sad Wings of Destiny, Stained Class, and Sin After Sin, I was wading around in my bicycle and catching the bus, which a lot of people probably don’t know so they never consider that. So the music portrays our lives, you know, as individuals and collectively as a band.”

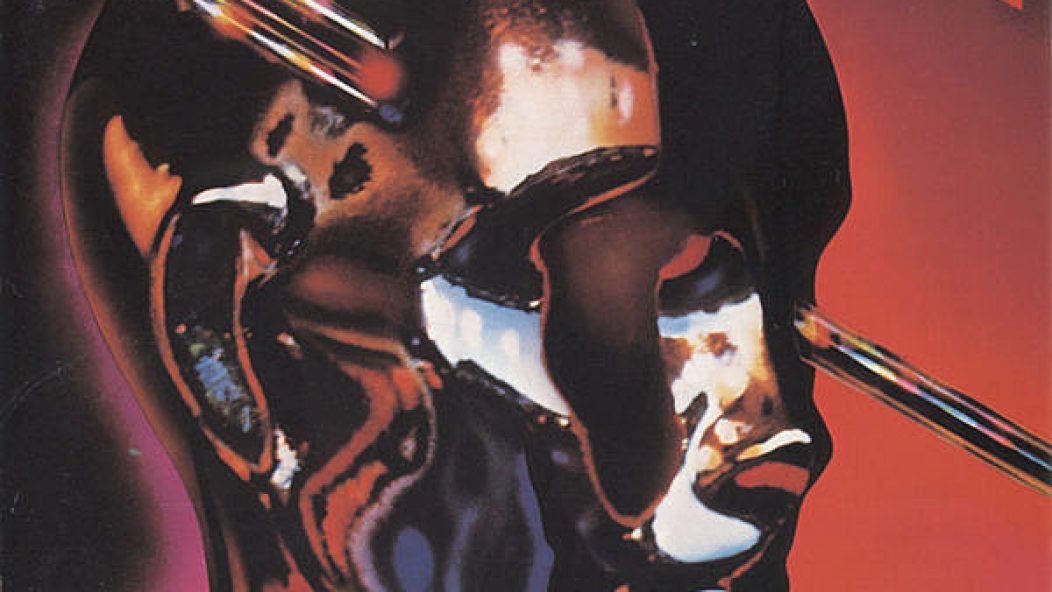

Between Halford scorning the ever-increasing cruelty of mankind in the title track, attacking false messiahs in “Exciter” and condemning Western annexation in “Savage,” his sights were set on the folly of man on Stained Class. Halford’s taut verbal venom was the ideal garnish for those songs: the title track’s galloping chugs and the war-torn apocalypse depicted in “Saints in Hell” were stuffed into short, deadly bursts that concentrated Judas Priest’s once-progressive tendencies. Accordingly, the artwork did away with the expansive landscapes and fiery imagery seen on Sad Wings of Destiny and Sin After Sin. Instead there was a lonely, reflective chrome figure with a laser piercing its head: a foreboding, menacing and cold concoction inspired by the title track’s themes of dehumanization.

“I think the idea here is in fact quite simply, that Roslaw [Szaybo]’s artwork portrays a class of people that don’t do things conventionally, let’s say,” Downing explains. “People that do things maybe illegally, immorally, in a corrupt fashion, a race of people that maybe are hidden between… you walk down the street and there’s probably a lot of people that you could consider are a stained class because what you see is not what you get, but that’s my interpretation. It’s something that you can’t always be aware of, can’t necessarily see, feel, or touch. But these people, you know, can be around or maybe they were a race of people that existed in the past or a race of people that will exist in the future. And maybe they might look exactly like the artwork, who knows?”

The majority of Stained Class was rapidly recorded with Dennis Mackay at Chipping Norton Studios. In contrast to the bleak themes on the record, the production on the album featured a bright and glossy sheen. Most notably, Tipton and Downing’s guitars had yet to become the razor-sharp knives first heard on Unleashed in the East, slicing cleanly and clearly instead of bloodily slashing and tearing. Binks in turn saw his cymbals pushed to the forefront while his snare and kicks were relegated to back alongside Ian Hill’s bass. It made for an engineering job that had more in common with a John McLaughlin solo record than Machine Head. While the choice to work with Mackay was a band decision, Binks was the one most familiar with his prior work with a variety of jazz fusion artists like Mahavishnu Orchestra and Jeff Beck. The crisp, sleek production matched the band’s sharp new logo, which continues to adorn Judas Priest releases to this day.

“I really liked the original logo myself,” Downing admits. “I think the truth was in fact, we had an ongoing situation with the first record company, Gull Records. We recorded Sad Wings of Destiny and Rocka Rolla with that company. And I guess that the original logo, there was a certain potential that the record company would lay claim to the logo… but I think that there was probably some legal advice going forward because we walked out of that record contract with Gull Records, so they got to keep and maintain all the rights and all of the income from those first two records. We never received any money at all from those records,” he laments. “And so we walked out because they weren’t doing the band justice and we went with Sony. And I guess, you know, with the anticipation that it might end up in a courtroom, we detached ourselves as far apart as we could with anything to do that related to the first two records. I’m pretty sure we used [the original logo] on Sin After Sin as well but maybe the legal advice came later on, if you know what I’m saying.”

There was one outlier on Stained Class however. One additional song, a cover of “Better By You, Better Than Me” by Spooky Tooth, was recorded at a later date with James Guthrie, who was best known for his work with Pink Floyd. Years later, the song became the focal point of a lawsuit where Judas Priest were accused of being responsible for two teens’ attempted suicides. The parents of the teenagers alleged that the band had included backmasked messages in the track, subliminally convincing the teens to carry out the act. The lawsuit was dismissed, and the trial was captured in the documentary Dream Deceivers.

…

DREAM DECEIVERS: HEAVY METAL ON TRIAL from First Run Features on Vimeo.

…

While the band was embroiled in the case, Binks (now 11 years removed from Judas Priest) kept up with the events intently. “It must have been over ten years after we made that album that that court case came up in America. And, you know, I was no longer in the band, and I watched it on TV like everybody else did. And I thought, ‘This is ludicrous,’ you know?’” he says. “And I thought, ‘Well, how come it’s taken so many years for anyone to come up with such a ridiculous accusation, of subliminal messages, all that crap.’ I was there when the album was being made, I knew that none of that had any credibility. And it seemed ridiculous to me that anyone would suggest that, you know?

“The guys were all hungry for success, as any young band is, and the fans were fantastic. I was really impressed with the loyalty of the fans. So to suggest that we would deliberately put subliminal messages on a record to encourage people to take their own lives is absolutely ludicrous,” Binks explains. “No, who’s gonna buy your records if they all commit suicide, you know? It’s daft. And who would want to wish that on anyone, you know? You’d have to have a very bent, warped mind to come up with something like that. But anyway, I thought this was crazy. I was watching the court case because a lot of it was televised in America and also over here [in England]. So I was totally bemused by that one, and it got thrown out of court in the end, quite rightly.”

Though the lawsuit caused trouble for the band over a decade later, it was business as usual when Stained Class was released on February 10th, 1978. More touring, more writing, and more recording would have to follow for Judas Priest, who remained at a working-class level. The scope of their achievement was not yet apparent, but that did not lessen the magnitude of the record’s accomplishment. The idea of heavy metal as a reimagined take on the pop song — a fast, serrated, chugging, and propulsive arrangement separated from the blues — was a new idea that the likes of Black Sabbath, Scorpions, and Rainbow had hinted at, but that Judas Priest had fully accomplished on Stained Class. It was a focused artform that the upstarts in the NWOBHM built upon with the likes of Saxon’s Wheels of Steel and the first Iron Maiden records. Even Black Sabbath themselves took influence from the movement with the borderline upbeat assault on “Neon Knights,” which opened Heaven and Hell in 1980.

Priest used the templates heard on Stained Class as a jumping-off point as well. Their next record Killing Machine, released later that same year, firmly built upon the foundation laid by its predecessor. Downing and Tipton’s guitars gained much needed girth while Halford traded his haunting, grandiose wails for the commanding, anthemic, and downright sleazy growl that tramps throughout “Evil Fantasies.” The distilled doses heard on Stained Class became curious cocktails: Binks’ funky beats litter the bouncing “Burnin’ Up,” acoustic guitars take the lead for Halford’s heartbroken lament “Before the Dawn,” and Tipton and Downing’s single-note, downpicked grinds carry the mean attacks in “Hell Bent for Leather” — their right-hand chugs went from harbingers of heaviness to carriers of catchiness. Within one year, Judas Priest managed to not only achieve heavy metal’s final quantum leap, but expand their accomplishment across the musical spectrum.

…

…

Killing Machine was the final Judas Priest studio outing for Binks, who left the band upon the conclusion of their next round of touring. Though it was the first album to successfully capture Priest’s sonic savagery, the live record Unleashed in the East paved the way out for Binks. “I was a session guy in the band, so I wasn’t contracted to the record company. And when we went on tour in Japan for the second tour I did in Japan, I had picked up a new kit there from Pearl. But when I got there I noticed at the back of the venue there was a 24-track mobile recorder being set up by CBS-Sony,” he remembers. “When we were in Japan, they were setting up all the recording gear, I said to the manager, ‘What’s happening about the recording because we haven’t spoken about it? We haven’t made any deal on this.’ He said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it, Les. It’s just for CBS-Sony’s sake, you know? If we wanna do anything with it we’ll sort it out later.’

“So we went straight from Japan to the USA and did a big tour of America, and then we came back to England, Britain, and we did a British tour up and down Scotland. The band was getting bigger and bigger all the time, and climbing that ladder of success,” Binks says. “We took some time off after that tour, and I got a phone call from [former Judas Priest manager] Mike Dolan saying, ‘Could I ask you to come into the office? I want to talk about the band’s next move.’ So I went on into the office and I sat across the desk with him. He said, ‘They’re at Startling Studios with Tom Allom.’ This was the first time they’d linked up with Tom Allom as a producer. And he said, ‘Been listening to the recordings from Japan. It sounds great, it all sounds great, you know?’

“I said, ‘That’s great, fine. Just pay me what you paid me for the last album.’ He said, ‘Well, Les, I think you should waive your fees on this occasion.’ So I said, ‘Well, you think I shouldn’t get paid for it and I shouldn’t make any money from it?’ That was when the shit hit the fan, you know, and everything went pear-shaped from then on,” Binks remembers. “That’s the kind of character I was dealing with and that’s the reason I left the band, because I realized I was having to deal with dodgy management, and nothing to do with the band. I never had an argument with anyone in the band. We all had the same goals, we all had the same, you know, musical direction.”

Though Les Binks’ time with Judas Priest had come to an end, his contribution to metal was immortalized with his three releases with the band. Unleashed in the East removed the context of time from Priest’s accomplishments in the 1970s, rendering the material with an aggressive and explosive production that remains potent to this day, while the exploratory and inquisitive Killing Machine offered many paths forward for the rest of Judas Priest’s wave-like career.

…

…

By the end of 1978, Judas Priest’s existence was a quantum superposition of states. Like Schrodinger’s cat, the band’s futures were infinite. One interpretation says that the superposition ends upon observation: the release of British Steel is where we see Priest’s career definitivelly resume towards ever-leaner, even tighter heavy metal. Another theory says that there exists infinite Judas Priests: one that made a thrash metal record after Killing Machine, one that embraced funk and disco even further, and maybe even one where Glenn Tipton invested his earnings from “Take On the World” into Apple Computer and retired at 32. But it was Judas Priest’s effort and achievement in 1978 that allowed these possibilities to potentially exist. The particle-like behavior observed on Stained Class set the stage for all that was to come, for both Judas Priest and heavy metal music itself. It’s not the wildest assertion for K.K. Downing, who easily zeroes in on that era as a special one for Judas Priest.

“I think around about that time — Sin After Sin, Stained Class, and Killing Machine — we were kind of in a unique zone really, especially Stained Class and Killing Machine,” Downing remembers. “Those two records for me really do stand out, more so in the Judas Priest catalog, as having an identity, songwriting, and recording that’s unique not only to Judas Priest but unique globally really. I think that the songs, the sound, the recordings, everything that we did was a very, very kind of a pivotal point in not just Judas Priest’s career but in music in general really, because they were the precursors really to a major change, and that major change would come with British Steel for Judas Priest,” he acknowledges. “A transition was taking place during Stained Class and Killing Machine I think.

“But what was really special about it was the music that came out and how it sounded. And I know when I listen back — out of all the Priest catalog — when I listen to Stained Class and Killing Machine, we were young men. We were kind of still journeying through our musical lives and careers, not knowing where it would go, when it would end, would it ever start, would it finish, but our creativity pulled us through that period. But we wanted a way to the future really, which was British Steel and heavy metal.”

There’s comfort in knowing the origin of the things that are important to us, heavy metal included. Tracing artistic influence, whether it comes in the form of beats, melodies, or tempo, allows music to become that much more relatable, human, and strengthens our connection to it. For the unexplained however — for a musical genre as utterly bizarre, unique and multifaceted as heavy metal — quantum theory can illuminate the unknown. Forty years ago, on February 10th, 1978, Judas Priest made that final leap that heavy metal needed to exist as its own ever-evolving movement. It was only fitting that while nearly every one of their peers rejected the label, Judas Priest embraced it wholeheartedly. They owned their achievement, and welcomed all that came with being a heavy metal band.

“I think the fact that people did identify us as a heavy metal band, we thought that’s really cool because to start with, there weren’t very many bands around that were being called heavy metal bands. And a lot of them kind of denied their divinity really,” K.K. Downing says. “A lot of bands said they were not heavy metal because I think they thought that they would lose fans, you know. There was the whole imagery around a rock band — have a good time, have fun — whereas this heavy metal music, no, it was not that really. It was more akin to the original concept of working class music like for example, the Delta blues. It wasn’t designed for people to have fun. It was working class, blue collar… ‘We are the band that’s here for you people, we understand and know that life probably has already been difficult for most of you, but you come with us and listen to our music, enjoy the show, and engross with us, and interact with us, and we will have an uplifting experience that isn’t just out and out fun with laughter and jokes.’”

“It was past and north of rock, and it was actually north of heavy rock. It was a coming of an age that was bound to happen I think, where music would crossover into being not just loud anymore,” Downing explains. “It was the energy, the look, the attitude, and the sound. Then it kind of just went on from there and I guess, the rest is history.”

…