Riffage: Today Is the Day - "Mayari"

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgFVR8vTrog

Today Is the Day – “Mayari”

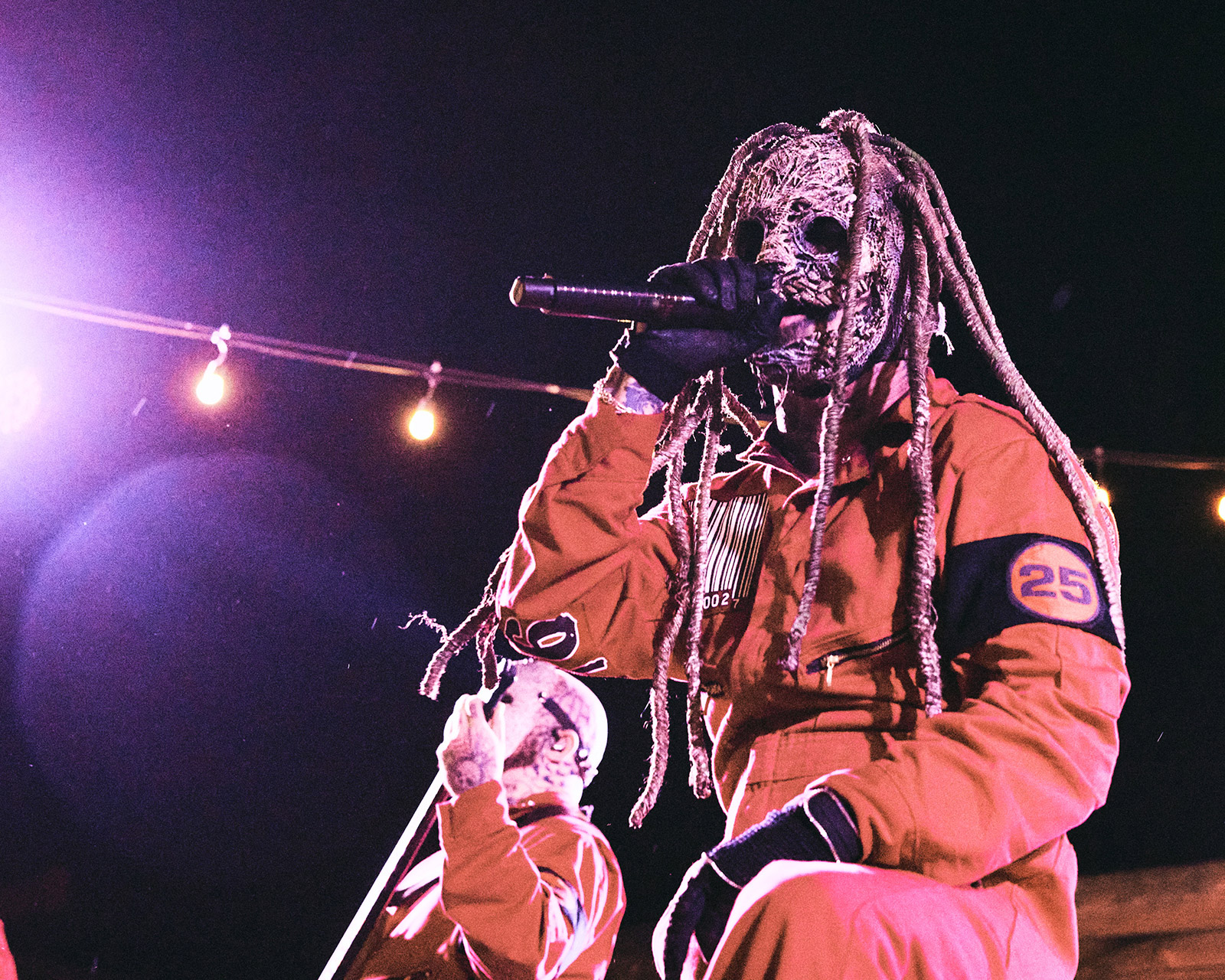

Front page photo by Wade Gosselin

. . .

Steve Austin is the most credibly bonkers man in metal. There’s no telling what a man like him would choose as an alternative if he didn’t have Today Is the Day as the outlet for an imagination that births songs like “The Cold Harshness Of Being Wrong Throughout Your Entire Life” (how’s THAT for an argument to fund arts education?) And, man, good for him. This life certainly gets rough, and we all have to create ways of letting it out when need be.

Moreover, I believe the bleakness Austin taps into is something collectively felt, digested by him like an Amazonian shaman, and spit back out to purge the listener of the demons lodged within. Mystical musings aside, Today Is the Day dredges up something for me that no other band can, and most of that has to do with the psychotically bizarre riffs that could come from no other mind but his.

Like Stephen O’Malley, Steve Austin strikes me as being either completely self-taught or the recipient of a Jason Bourne-style mental strip mining that removed any traditional guitar player defaults; they just do things that other guitarists don’t. That makes their playing instantly identifiable, and more importantly, capable of producing new images and textures.

Perhaps more than any other song in their catalog, “Mayari”, off my favorite TITD record, 1999’s In the Eyes of God (featuring the proto-Mastodon-ian touch of Brann Dailor on drums and Bill Kelliher on bass) has the mojo. Like a good Dario Argento film, it conjures the mind’s eye demons for me every time.

First, our tech considerations: tune your low E down to B. then dial up a respectable amount of gain (duh).

. . .

All times reference the above YouTube video

. . .

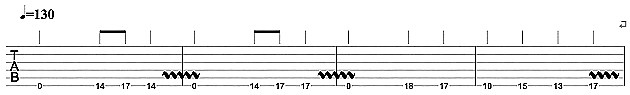

[Riff A – 0:00]

. . .

. . .

What guitarist in his right mind would sit down and write this tangle of a riff? The one and only correct answer is Steve Austin. This riff springs from savage vibrato and an idiosyncratic melodic pattern. You really have to mangle your string to get the right feel here, so the looser they are (from down-tuning), the better. Hit those low Bs extra hard to get the appropriate detuned B’WOW on the downbeat.

Due to the dropped-B tuning, it makes the most sense to perform this riff on one string. This tuning also creates some interesting chordal possibilities, as we’ll see later. To paraphrase Robert Fripp (who developed his own guitar tuning system based on fifths), standard tuning is essentially arbitrary. There’s no reason why every guitarist shouldn’t experiment with tunings until she or he finds one that suits their approach. It’s also a fantastic way to get yourself out of compositional ruts. In the case of dropped-B, the standard power chord shape on the bottom two strings now becomes an octave, preserving a functional relationship between those strings. This lends the heaviness of a baritone tuning while offering the traditional range of the standard-tuned guitar.

Melodically, Austin doesn’t often play inside the pentatonic “blues box”. Many of his riffs reference Eastern melodies, but he’s not really couched in that world, either. Overall, there’s a sense of abandon in his palette that sets TITD apart from most metal subgenres, an unbridled aesthetic yielding a Pollock-esque splatter by trusting and following spontaneity. It sounds as though Steve Austin writes, plays, and even mixes every Today Is the Day song like he has a gun to his head.

. . .

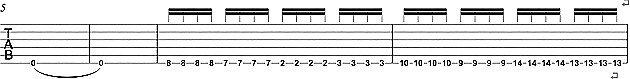

[Riff B – 1:34]

. . .

. . .

This is the next primary riff of the song. The low B drop provides a spacious landscape for Austin’s perpetually brimming psychosis, while the interstitial “jugga-jugga” pattern stokes this malevolent machine along. Beware the jags of rusty gears and other injurious moving parts.

. . .

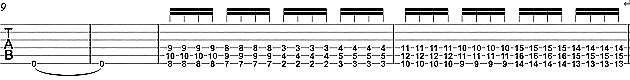

[Riff C – 1:54]

. . .

. . .

The same riff but the aforementioned “jugga-jugga” motif is now expressed with a creative triad voicing facilitated by the drop-B tuning. The proximity of the octave and the high third to the low root creates a clear, complex chord that orchestrally approximates a guitar/bass hybrid.

. . .

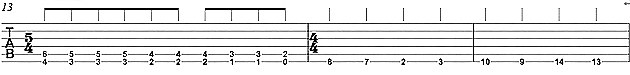

[Riff D – 2:26]

. . .

. . .

The last variation. Note the time change to 5/4 in the first half of the riff. This is the final wholly unique riff featuring a chromatic descent to parallel the psychological one that “Mayari” drags us through: the perfect end to a perfectly sculpted bummer of a tune.

Take care, and please feel free to add suggestions for future “Riffage” features in the comments.

. . .