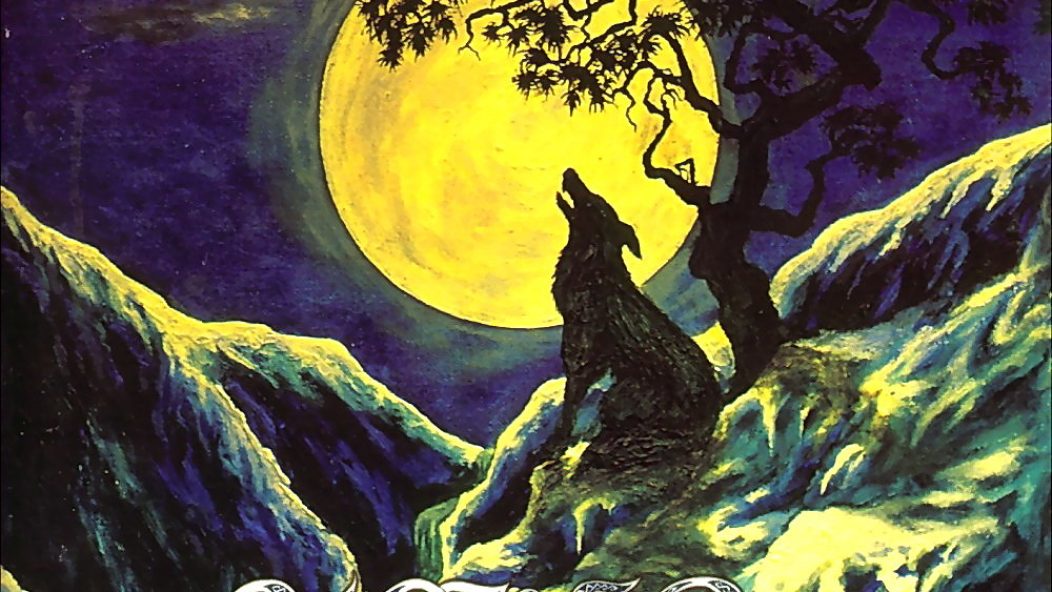

Of Wolf and The Past: Ulver Reflects on 20 Years of "Nattens Madrigal"

…

By some great cosmic anomaly, twenty years have passed following the release of Ulver‘s Nattens Madrigal. Closing their canonical Trilogie and preceded by Bergtatt and Kveldssanger, the windswept Nattens Madrigal‘s buzzing bore the incensed death throes of Ulver’s first chapter.

Following the first two chapters of the Trilogie, both of which widely considered to be hallmarks of black metal and neofolk, respectively, was difficult, and the public eye looked to Ulver to fill…their own shoes. In the shadow of two “beautiful” albums, who would expect such a powerful, raw display of frigid, animalistic power? Though its singular predecessors depended heavily on elements of progressive rock and Romantic folk music to create expanse, the myth-enshrouded and unexpectedly harsh Nattens Madrigal‘s explosive presence spoke to the fury and rigor which defined the more traditional end of Norwegian black metal’s second wave.

In his liner notes for Century Media’s latest reissue of this landmark album, former Slint guitarist David Pajo meditates:

“The pops and clicks … You can literally hear them plugging in their

guitars. And they left it on the record because they don’t give a fuck!And of course there is the ferocious, unrelenting speed. From start

to finish.But there is so much more happening if you can look past the tempo

and fuzz (which I love, I should say).Listen to the guitar interplay. Both guitars are constantly moving

separately yet in unison. There are beautiful, sweeping chord

progressions with victorious, marching melodies played within them.This is exactly what people miss when they talk about black metal.

When done right, there is passion. Deliberate, raw passion.The vocals are emotionally unforgiving. The archetypal voice for this

kind of music – true perfection.The melodies build tension, swell, and erupt like a grand orchestra of

pure hate. Hate for what? Well remember, in the 90s there was quite

a lot of shit to hate.

-David Pajo, 2016 [Century Media]

In a special interview, Kristoffer “Garm” Rygg, Håvard “Haavard” Jørgensen, and the previously silent Torbjørn Heimen “Aismal” Pedersen reflect on and fondly remember the circumstances surrounding their legendary album, meditating on philosophy, tackling rumors and myths, and their legacy two decades later, accompanied with some never-before-seen photos from the Trilogie-era.

…

…

Though you had an opportunity to reflect with the Trolsk Sortmetall 1993-1997 box set and booklet, celebrating an album’s twentieth anniversary is truly a milestone in a style as relatively young as black metal. Upon composing and recording Nattens Madrigal, did you expect such a rabid following? How do you view the album now that two decades separate you from its release?

Håvard Jørgensen: Has it really been twenty years already? Now I just feel old. Most of Nattens Madrigal was written by Kris and myself at my mom’s house in the spring and summer of ’95, and though we had a pretty good feeling about the songs going into studio, the scene at the time was kind of anti-everything and prided itself on “not being for normal people”, so to speak. Of course no one predicted the place it would later earn in ‘black metal history’.

To be honest I had not heard Nattens Madrigal for quite some time before the remastered version on Trolsk Sortmetall 1993–1997. I was just happy I could finally hear the riffs again. But what can I say, I think it holds up quite nicely – and I also feel it was the perfect way to end that trilogy really.

Kristoffer Rygg: I neither listened to this material for a long time, but when I do now, it is with a much more forgiving view on some of the choices we made at the time, riff-wise, production-wise, you name it. I just enjoy it for the feral discharge it is.

I have occasionally eavesdropped on newer albums that go for a similar vibe or sound, but for some reason Nattens still has a kind of raw power to it that’s hard to put one’s finger on. Of course it is very much tied to the scene and the days in which it was created – or spawned. We were young and our world was much smaller then. And as Håvard says, we had very little regard for what “normal people” were into, or what was considered to be in good taste or whatever. In that sense, there might be an earnestness to Nattens Madrigal that you maybe don’t come by too often anymore, I don’t know.

Torbjørn Heimen Pedersen: It was impossible to predict how it would be received. And, the fact that I am being interviewed about it 20 years later is beyond belief. But looking at it from a distance, I can understand what people hear in it. Not many albums sound just like this one. It’s a unique piece of art.

…

…

Kristoffer mentioned the production, which is generally the first aspect of the album people mention. Making such a raw, biting album in the wake of Bergtatt and Kveldssanger‘s clarity was a daring move which is still polarizing. What made you close out the Trilogie in such a brazen fashion? Looking back, would you have approached the production in a similar way?

H: To an extent both Bergtatt and Kveldssanger were regarded as relatively “beautiful” albums, so there was an internal need to push the envelope after that, to do something more grim and ugly! Whilst I was mainly preoccupied writing riffs, I remember Kris and Erik had a very clear vision of a so-called necro sound. I remember using a super simple setup with just a Boss Metal Zone and a Marshall JCM 800 – all cranked up and dialed hard right. And if that wasn’t enough, there was added even more treble in the mastering process.

K: That’s true. On one hand we were black metal kids, into rugged sounding demo and rehearsal tapes, and of course the first releases by Immortal, Darkthrone etc. But on the other hand we also loved the melancholic, dare I say liturgical, aspects of certain doom metal bands, prog rock, folk and classical musics. I guess we were trying to prove a point with our two first albums, that black metal could also be beautiful and dirge-like or whatever. But we were ultimately black metallers at heart, and Nattens Madrigal was very much about solidifying that stance. I remember Burzum had this track called “Feeble Screams from Forests Unknown”. It’s quite descriptive of the ideal black metal sound to me, allegorically speaking. The production was a conscious aesthetic choice, and it works almost like a filter – one that enhances the mood.

I would argue that a lot of the nineties black metal stuff, now considered “kvlt” or whatever, often feels the way it does because of the crappy recording and production values. It’s the same deal with Nattens Madrigal really. It’s meant to hurt, and would most certainly not be the same with a pleasant production.

T: We, and maybe especially myself, were very happy to finally release a full-on black metal album. After two “tempered” ones we felt we had to end the trilogy in a proper manner. When all is said and done, we were part of the black metal scene of Norway. In hindsight, I might have opted for a slightly better sound, as the album is just so full of great riffs, but then it might not have felt so mystical. Anyway, the remastered version is now out to remedy that issue.

…

…

That sudden, distinct shift into a more conservative, style-directed sound definitely caught the uninitiated off guard, and still does to this day. People don’t know how to process change so the rumor mill definitely turned. I’m sure you’re aware of the various myths and legends surrounding Nattens Madrigal (the cabin in the woods, opting for a 4-track recorder, certain behaviors), and I apologize if this is a sensitive or overwrought issue, but is there anything you could offer to either quell or further steep the mythos?

…

To further quote David Pajo’s testimony:

”[…] there is no shortage of mystery and rumor around this record.

Heshers have told me various things; most famously that they used

Century Media’s recording budget to rent a limo and buy Armani

suits for a very “un-black metal” photo shoot. Which, true or not, is

hilariously brilliant. I was also told that it was recorded in a forest on

a crappy little Fostex cassette four-track.”

H: I don’t know the origin to this rumour, perhaps it was something Century Media wrote in a press release or something? It was all part of making Norwegian black metal seem as ’exotic’ as possible to people abroad I guess. The more extreme or far-fetched the better. We did use 4 and 8 track recorders, but only for rehearsals and demos… We also did in fact compose large parts of our first album, Bergtatt, at a wooden cabin. But yeah… it’s a good rumour, one that has kept haunting us. The studio we recorded Nattens Madrigal in was a pretty basic early digital ‘hobby studio’ I remember. The Mysticum guys knew the guy who had it and suggested we just track it there. I think it had 12 tracks, maybe 16. It was not very fancy and it was somewhat out in the district, but not exactly out in the woods either.

T: Actually I didn’t hear the rumours about the woods and 4-track until many years later. Not quite sure what you mean by behaviours…? We were nice and clean boys, “from furnished homes,” as we say in Norway.

…

…

Now that time has passed, do you think the rumors added to the album experience overall? That is to say, did it add a layer of unintended meaning or characterize it with an unexpected mystique?

T: I guess it did. Myths have certainly helped bands such as Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Eagles, to mention a few. So why not Ulver? And maybe the label did it on purpose, I dunno. Or maybe it didn’t come from them to begin with? But despite all that, I can confirm that it was recorded in a studio. It really didn’t feel like a usual studio session though. We kept it intentionally very rough and simple. I just plugged into a pedal and some amp I borrowed (maybe a Peavey), recorded my parts, and that was that.

K: No matter where that rumour originated it obviously didn’t hurt. Not that we intentionally did anything to fire up under it or anything, but we did of course realise at some point that it was great for the album, and for black metal in general, to be circulated by a bit of whisper. I’d argue that any band or album, really, will benefit from having something “extraneous” going for it. A good story. Take a band like Mayhem, it’s pretty hard to think about them on purely musical grounds, without considering their bizarre history. I think it’s safe to say that the stature they enjoy now has as much to do – if not more – with what, eh, happened, as with the music itself. But this can of course be said about many bands. I mean, imagine Velvet Underground without Andy Warhol? Joy Division without Ian Curtis, you know? It’s interesting to see how certain things become so mythical and romanticised with the passing of time. I guess when the stories are relayed enough times they ultimately take on lives of their own and fiction becomes reality.

Anyways, back to Nattens Madrigal. I guess it has had this curious kind of “shelf-life” because it has just existed on its own in an underground world that has since grown into a worldwide phenomenon – we were never really there to dispel this or that rumour. The abandon that came after it, the fact that we never really followed it up. All those things have helped cement the album’s position I think

…

…

You definitely embraced some aspects of the rumor (which have since been dispelled) before making the big shift toward what would eventually lead to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell – I recall a photo set of the full band, clad in suits, surrounding a sports car.

H: By the time the press photos were to be taken, we had become a bit fed up with the standard ‘black metal fare’ to be honest. We thought it would be a pretty funny contrast to the ‘necro’ music we had just released as well as a little ‘up yours’ to all the black leather clad, bullet belt wearing hordes who had suddenly popped up everywhere. Nattens Madrigal, as I said before, was actually written in 1995, and by the time it was released it was in many ways already a thing of the past for us.

The rumour about the recording budget being spent on Corvette and Armani is of course also just a hoax. We borrowed the car from a car dealer buddy of Kris’ father and the dresses were most likely standard issue. What more can I say? Those photos were more or less a humorous stunt from our side, especially considering we had just taken a step up from an underground status to a big international label and such.

K: That’s right. I also remember that this was in the midst of winter, and there was no way to actually drive that car up the icy roads to Holmenkollen (where those photos were taken), so we had to transport it on a car hauler. It was basically calling in on a lot of family favours to get that shoot arranged. I also remember blasting the Dr. Octagon album full throttle from the car once parked and in place. Doesn’t get more black metal than that.

T: Memories, that was one of the funniest photoshoots we ever had. We never were a particularly conform type of black metal band to begin with, that with painted faces in the forest (hence the piano, flutes, classical guitars, mythology…etc.), thus we could just be free and do whatever we wanted as far as I’m concerned.

On a side note, and considering the “furnished homes” I mentioned above, I should mention that I didn’t have a proper suit for the occasion. So I had to rent a really cheap one. Therefore I kept myself in the background, leaving the pretty Armani boys in front.

…

…

Along with the mythology surrounding the album itself, Nattens Madrigal‘s subject matter was the first time Ulver fully focused on the band’s wolfish aspect, centering and bringing together the name (note to the readers: Ulver means “wolves”), solitary ideology, and execution. From then on out (and to this day) the band and its members were referred to as “wolves.” What brought about the subsequent, more outward wolfish identity? Did Nattens Madrigal kick-start this shift?

K: Both yes and no. Being black metallers we naturally had an interest in the so-called Left-Hand Path, ideology and psychology, Jungian archetypes and all that stuff. I remember reading a few articles about lycanthropy in The Fifth Path or The Black Flame or some other “Satanic” journal of the time, and it made an impression. There you also had features on musical acts such as Radio Werewolf and NON, which we were kind of into. And the Company of Wolves movie, that was definitely an influence. Oh, and Altered States. We really liked the “animal consciousness” and “feral man” aspect of that one, which is dealing with related topics, albeit in a more transferred sense. So, it came from a lot of places really. Obviously, the wolf is already a strong presence in European folklore and Norse mythology, so in many ways it’s something that had followed us since childhood almost. It all started with Little Red Riding Hood.

For Nattens Madrigal, however, we decided that we should go all in with our “wolf concept”. It made perfect sense considering the band’s name and some of our personal aliases. I remember doing quite a bit of research for that one. Soaking up Sabine Baring-Gould, Montague Summers, Gothic fiction as well as Shakespearean tragedies, you know?

We adopted the wolf as our totem animal, and it’s been with us ever since. But never in such a direct way as on Nattens Madrigal, of course. When we, or others, refer to us as wolves now it is in a more “warm”, self-ironic way.

Interesting that you bring up tragedy – I had always wondered if Nattens was more than a romanticizing of lycanthropy, especially given some of the morose passages which weave their way through the evil, fierce music. Does that tragic angle – the loss of humanity as one becomes the Wolf – play a part in Nattens Madrigal?

K: Well, yes. As Haavard said before, we had become a bit weary of the whole “eviler than thou” shtick by then, and we did ultimately want the album to feel more nuanced than what was perhaps common for black metal bands at the time. It definitely tackles feelings of ambivalence, being torn between two things. Hatred and rage, certainly, but also love and longing, you know? And it does end on a tragic note, I would say, with the death of love and a point of no return set of circumstances.

I found it intriguing the Trilogie ended on such a powerful symbol of “finality” – the death of love, the loss of humanity. Obviously, as Haavard pointed out before, the music in Nattens Madrigal was already a few years old upon its official release, but did it feel like death when it actually was unleashed? Ulver underwent some big changes thereafter, both in direction and lineup, so was death and finality the intent, or was it more serendipitous than that?

H: By that time we’d all grown a bit older and were young adults, having to make the typical decisions like whether to pursue a musical career or “get a haircut and a real job” etc. Also, we had all begun to feel the contours of something different happening musically, as well as new approaches and methods of making it. Not everyone was on board with that, although I think we all agreed that we were done, so to speak, with the black metal perspective on things.

So Nattens Madrigal became thus a crossroads for us as a group, not only musically and lyrically, but also in life.

The wolves moulted, to use a fitting analogy.

T: It didn’t feel like death at release, even if it was ending a trilogy Kris and Håvard had planned for years. But eventually it did resemble death for me in the black metal scene. I was satisfied to have completed my personal wish to play on a real black metal album. Soon after that I arrived at an age where I concentrated on education, and could not put enough effort into the band. And then, when the music seemed to go a different way, I felt my days were over. So I did indeed retire, got a haircut and a proper job.

…

…

It certainly seems that the “moulting” was happening in the background over a greater period of time, especially when the “older” material on Nattens Madrigal is placed in the greater timeline of Ulver’s discography (the Marriage of Heaven and Hell double album seeing a release the following year). Though the attitude you mentioned earlier surrounding the band photo certainly offers some insight, how did you handle press coverage during this strange time of transition? Was it frustrating focusing on this material, now a few years old, when other, much more adventurous music was being worked on?

H: Well, now I’ve probably made it sound like we weren’t into Nattens Madrigal, which is obviously not the case. We were really proud of that album, and felt we had created a proper beast. What I am trying to say, I think, is that we had simultaneously come to a place in life where a lot of other concerns had made themselves known, both individually and as a group. And the dynamic in the band changed accordingly. I never did any interviews around this time, but I believe both Kris and Erik did quite a few, where they discussed the album and its concept as far as I know.

But yes, it was clear that things were changing around 1997, and Themes From William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, that followed, is the evidence. That album was not created in a rock-band-in-rehearsal kind of way, at all, like Bergtatt and Nattens [Madrigal] were. Knut (Arcturus) and Kris had set up their own studio and were practically living in it. In fact, Kris was quite literally living in the first Jester studio for about a year, so they could afford paying the rent and such. At the same time Tore (Ylwizaker) had gotten quite heavily involved. Me, Erik and Hugh also participated on that album (Themes…), but obviously not to the same extent anymore.

…

And so, we close with Pajo’s triumphant dissection of Nattens Madrigal at its core.

“On the surface, Nattens Madrigal appears to be a buzzy, lo-fi, black metal

album. But if you can let yourself absorb what simmers beneath,

you’ll be rewarded with a clever, orchestrated, impassioned recording

with tremendous depth and fervor”

Take some time and allow this special album to completely engulf you in its morose, fierce, timely static.

…

Digging into what many agree to be one of the pinnacles of black metal ended up being both an enlightening and emotional experience. Many thanks to:

Kris, Håvard, and Torbjørn for their time, insightful answers, and artistry.

Valnoir for providing previously unreleased photos.

and

David ‘Papa M’ Pajo (ex-Slint, Tortoise, Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy) for giving us his blessing to quote his Nattens Madrigal reissue liner notes.

And many more – without your input, this feature wouldn’t have happened.

Ulver’s has an upcoming new album, The Assassination of Julius Caesar, which will be released on April 7th by House of Mythology. You can read more about it here.

…