Timeless Truth: Meshuggah's "obZen" Turns Ten

…

Back in the day, in the pits of kitchen hell, we’d all listen to Meshuggah while drinking PBR in coffee cups. We’d call it the “Frank Booth Special.” One fellow chef would always remark how happy Meshuggah’s singer sounded. He was being facetious of course, but every time the Swedish juggernauts would spawn their cubist patterns across the kitchen’s speakers, it never failed.

“Boy, he sounds cheery,” he’d snicker. “Maybe he needs a hug?”

I was always in awe. Even though the band’s aggression was apparent, it certainly wasn’t about one clear “thing” with this group. For me, Meshuggah was art music. Anger was superfluous: simply an angle they used to reinforce their multifaceted prism. Wasn’t that obvious? Weren’t they more jazz (metaphysically) than heavy metal?

That was something like 2007 or 2008. The kitchen was a wild place to be. We’d have a little stand on the line for playing CDs or tapes, and during the crossover of the day and night crews, albums like Purple Rain, Junta, and Kind of Blue were popular. After the day crew fled, things would get a little more twisted. From cassettes filled with the sounds of the animal kingdom in heat to CDs by Fred Frith and Ikue Mori’s Death Ambient, it was a diverse space for some imaginative (and hard living) cooks. Enter Meshuggah’s obZen: an album we played a significant amount, particularly for the end-of-night clean-up. It was a nasty job that needed a spiritually cleansing soundtrack.

Meshuggah released obZen ten years ago today, a silverish record that saw the band reach a point, methodically, it hadn’t yet. By chance, I bought the album the day it came out, and preceded to bus it up the hill and into work. obZen will always be a great reminder of that time — it stood for a particular feeling and energy that was about space and imagination. Meshuggah could offer you help with physical labor and also intellectually force you to explore. The record was the sharpest and most stinging the band had yet sounded, bending time in a distinctive way and further distancing the group’s sound from a definitive heavy metal one.

Looking back even further, the first Meshuggah record to enter my universe was 1998’s Chaosphere: the most barreling and suffocating record I’d ever heard. My friends and I would drive around smoking spliffs cranking it, and it’d just blow our minds. The album was alien: otherworldly, something from a galaxy unknown, and with it this band captured a darkness that was H.R. Giger and da Vinci rolled in one. As heavy and punishing as it was, it had an openness that was perfect and agile. Fredrik Thordendal’s guitar solos were like Pat Metheny on nightmare acid. The whole thing felt beautiful and immense — direct metal that was also pure art — reshifting everything I’d thought about the the genre, opening a door to the other side of the world.

I was never a huge “anger” or “tough guy” metal fan. My initial attraction to heavy metal was mostly through psychedelic vibes and instrumental awe. Punk rock was always real to me; heavy metal was sort of tasteless. Things changed a little down the road, but honestly, not that much.

Meshuggah though, was a force of metal that somehow had punk rock’s inner-spirit welded into its armor while still maintaining enriching and wild instrumentation — jazz that was metal and punk, and also encouraging, arty, and scary, like Primus and Arto Lindsay. They were inspiring. They made me feel like drawing or thinking, or sculpting something real and making it a part of my dream-system. And so I listened.

…

…

After experiencing Chaosphere, I dabbled with Nothing and I; these were great records, particularly I, which really extended the jazz vibrancy of the group. Thordendal is a noted jazz enthusiast, holding Allan Holdsworth (among others) as a major influence. You can hear it: there’s a cavernous depth to his soloing like a little avant-garde jazz duo echoing off itself in a tiny box. (Check this out). He’s a feeling player, sketching out solos without direct impression. His playing is more like an abstract painting, where you can feel the symbolism, rather than see it (or hear it) completely: there’s a hint of suggestion of effect and purposeful meandering. It’s like a dream more than a note. Thorendal even talked about jazz and his lack of formal training in an interview with Guitar World back in 2011:

My dad always listened to jazz, and I guess that influenced me to learn about improvisation. An improvised solo sounds so much better than a written one. For me, there’s not much thinking going on at all, only a reaction to what I’m being told from the inside.

And no, I have not had any formal training. When I record my leads, they are usually based on feel and totally ignorant to all laws of music theory. This, of course, is because I just play whatever comes out. There are no rules. But on certain songs, I do have to figure out what scales I need to use to follow chord changes. Since I’m not very good with all the scales, I sometimes have to write parts down and plan things ahead. I usually improvise the first part, then insert the written part and continue to improvise until the end of the solo. It’s a very confusing way to do it, but I do whatever it takes to make it sound like I know what I’m doing.

2005’s Catch 33 was notable for its use of angular precision and the Drumkit From Hell, a software synthesizer that utilized Tomas Haake’s drums, symbols, and kicks as samples. The theme of the album continued along the band’s noted methodology of progression and experimentation. The group had appeared long ago to become artists over musicians, and thus they evolved their system in a more natural way, releasing the band from any engagement in a production struggle. This method granted them the freedom from certain inauthentic expectations, e.g. overt regurgitation. The album though, while determined, missed the group’s galactic naturalism. It was there sporadically (most notably in Thordendal’s ever-stimulating solos), but the whole was somewhat incomplete.

obZen was Meshuggah realizing its true power. Lean, and crisp, the album was capable of taking their most wild bents and evening them out, creating something similar to a solution and gratifying compromise to the band’s hard work and fearlessness. They had figured out how to maximize their inertia. Moments were interwoven and open to exploration, yet pondered about circularly. While still extreme in the greatest sense, the record was less interested in blowing people to kingdom come than delivering a system to explore and progress their particular sound.

…

…

Like a jazz outfit, or even a band like Phish, Meshuggah created an environment that was partial to exploration. On obZen, they figured out the necessary system to make those adventurous juants even crisper and more immediate. The album had a Tool quality in its equitable minimalism. A more sculpted and fully realized sound, a product of the longest writing and recording process yet for the group. It is a equally challenging and digestible album: a work of art that sounds as immediate now as it did ten years ago. Haake talked about creating records that had longevity with The Skinny back in 2008:

I think in lots of ways our albums are slow-burners. To some extent this one is easier to digest, but the music is still very complex and I think that it takes a certain amount of will from the listener to really get the hang of it. For me, personally, that’s what I like. The albums that really treat me are the long-runners, the ones that I keep coming back to, year after year. We see that as a good aspect in writing an album and obZen is challenging the listener.

The album starts off with circular legs, positioning things to gauge like a cube trapped in a geometric maze; yet underneath the equation, there’s an unbridled organic quality. Like the band’s earlier works, the energy is infectious: a directness that clarifies the abstraction. Like jazz, there’s the possibility for limitless freedom within a contained structure. Meshuggah wrote the book on extreme polymetered riffs and polyrhythms, and obZen is masterclass in that regard. Like blocks of rigid concrete floating in the ocean, the dance is spiral and smoky, a haze hovering over the spouts of salt air sprinkles. Mostly, it’s about the art. Meshuggah is a group devoted to this idea. They play as one specimen. On “Bleed,” the group took that uniformity to the ultimate extension, developing a song with a continuous plunge, a never-ending linear mode. Back in 2008, Haake talked about the difficulty of playing the song and changing directions with Aquarian Weekly:

That one was the biggest challenge for me on the drums as well, learning it, and rehearsing it before we started recording. I probably spent as much time on that track alone as we did on all the other tracks combined, just because I had to kind of change the approach to how I played the kick drums. Now it’s more, for lack of a better expression, it’s more like tap dancing, more lightly. I’m more used to hammering the kicks with a lot of force, but this is kind of too tricky and fast to be able to do that.

…

…

Contrasting the vast horde of imitators that followed, Meshuggah is a completely original thing, like a yellow and diamond snake born from the sun. Its scales are technical and glassy; its head a monster of splitting atoms. Like my friend the chef from back in the day, there’s always a compelling (and oftentimes direct) reaction to Meshuggah. And that’s what real art does. It inspires a hoard of followers, creates obsession, and finds its way into the hearts of the open and needy: a direct path for life and movement. It did mine.

When I moved to Asheville, North Carolina, for a bit of a stretch, obZen really permeated my mindscape. That was a dark time, with strange grey horizons and eyes failing. There was nothing to grasp in the desolate fog, save for long drives through the tiny city and greater highways with obZen blasting, urging me through the transition. I lived for those jaunts: the sound, like an old friend of hope and extraction. The ability to maintain focus where chaos was all around: art drives through hell with the pauses in “Bleed” so infinitely haunting, that time dropped, and I could breathe, let my life pass through me.

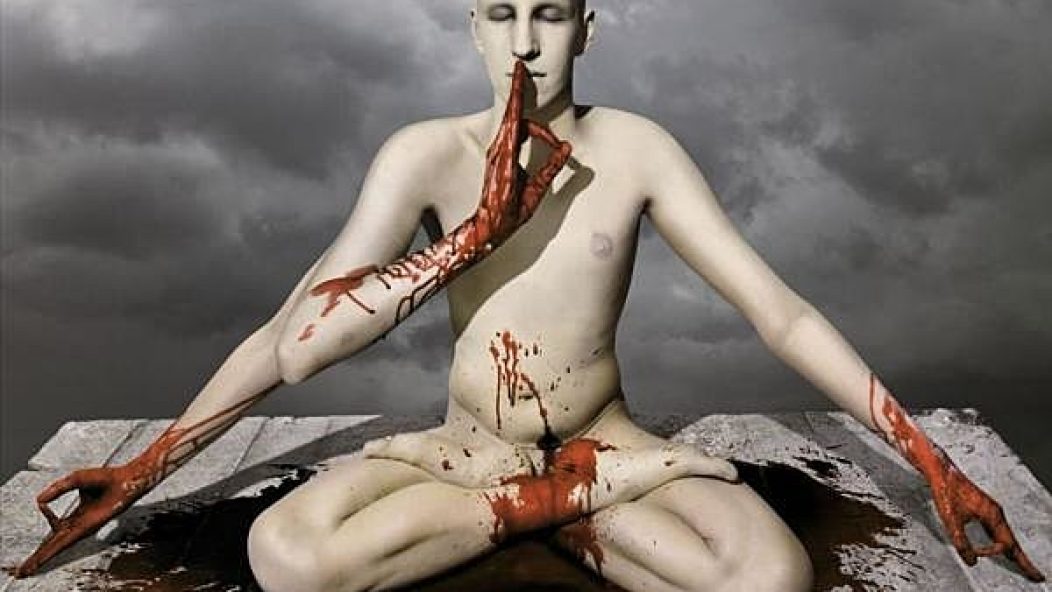

For obZen‘s ten-year anniversary, and for Meshuggah in general, I thought I’d draw some pictures dedicated to the whole experience. This was my way of living the album in real-time again. Like the way I experienced the band back in the day, in the kitchen, in the car, in Asheville and in the universe. I believe experiencing music should be unique to the individual. Once it becomes something outside itself to the listener, it drifts into a dead zone. The place it can’t truly live. Grab yourself your copy of obZen, put on your headphones, and take a walk alone. Sketch that corner building you’ve always wanted to, walk, and feel the Earth move ever so slightly.

…

…