Not All Who Wander Are Lost: Mat McNerney Pt. 1

…

I: The Musical Desert of Wimbledon

Mat McNerney called from halfway across the world on a Sunday morning, around the time most people would be getting out of church. For him, it was already dark. McNerney rang from his home in Tampere, two hours north of Helsinki, Finland — around 7,500 kilometers from where I sat in Seattle, but also 2,300 kilometers from his birthplace in London. His wife and writing partner in Hexvessel, Marja Konttinen, left us in privacy. Their upcoming album, When We Are Death, drops a week from today.

McNerney had just put their child to bed after rehearsing with one of his two current bands, Grave Pleasures. Even so, I could not detect any hoarseness or exhaustion in his voice. Judging by his crisp tenor, you’d never guess that he used to be one of the most unhinged vocalists in black metal.

Now an ex-pat, he came up in the English death metal underground and left his home country to be a part of the avant-garde Norwegian black metal movement.

…

…

McNerney grew up in Wimbledon, the same suburb of South London that hosts the storied tennis tournament. At age 12 he joined Vomitorium, a death metal band based out of his high school.

Vomitorium played more or less in an echo chamber. They released a cassette demo in 1995 which went nowhere, and then broke up as members graduated. “You’d go on holiday with your parents and you’d see a metal guy somewhere. Later you’d talk about it to your friends, ‘Oh, God, I saw this guy in an Autopsy t-shirt,’” McNerney said. It didn’t sustain Vomitorium; they released a single cassette demo in 1995, then broke up as members graduated and moved away.

For a while after, McNerney drifted. “I was kind of lost and stuck without anything,” he said in that interview. “The ’90s were a difficult time in Britain for finding musicians, […] Black metal was kind of petering out. And there really wasn’t a big scene in Britain for it.” It didn’t help that, by McNerney’s own admission, his guitar playing wasn’t as sophisticated as he wanted it to be.

He formed a more adventurous band called Void, one inspired by the progressive and industrial influenced black metal coming from Norway at the time, especially Dødheimsgard’s 666 International album. “I guess I was the biggest fan of that band in the world,” he said. This material was more adventurous than the more conservative take on the genre that briefly captured imaginations worldwide a decade earlier thanks to church burnings and the murder of Øystein Aarseth. It was a new kind of black metal, as different from Mayhem as Mayhem was from Venom. “There were other things going on in metal. Nine Inch Nails thing was very big, Rammstein and everything. That was filtering into black metal and we were really excited about that.” Like Vomitorium, Void recorded only once with McNerney: an album called Posthuman released on Samoth’s Nocturnal Art Productions label. Again, nothing happened.

II: The Brief Life of a Supervillain Outcast

Then he traveled to Scandinavia. “I was very into Scandinavia. I did this degree in Scandinavian studies. And I got to spend one year of it in Norway,” McNerney said. “That’s why when I started going to Scandinavia and meeting all these different musicians, it just seemed like there was a big scene there, with a lot of people playing, and it was lot easier to get bands going. That’s how I ended up doing these international projects.

Like his heroes, McNerney took on a pseudonym: Kvohst. After returning to the UK with a rolodex full of metal musicians, he met Andrew “Aort” McIvor, who had released an instrumental solo record in 1998 as Seasonal Code. Together they dropped the “Seasonal” and became Code. To fill the ranks, McNerney called on his Norwegian friends and enlisted Yusaf Vicotnik of Ved Buens Ende and Dødheimsgard to play bass and Erik “AiwarikiaR” Lancelot on drums. They recorded an album in 2005, Nouveau Gloaming. McNerney said, “It was almost like a Norwegian sound, a Norwegian tribute. We recorded in Finland but we mixed it in Norway, so it really felt like this kind of early ’90s Norwegian black metal album.” In retrospect, as odd as it is, that album is a bit tame compared to what came after.

That same year, Bjørn “Aldrahn” Dencker Gjerde left Dødheimsgard and McNerney took his place. They released Supervillain Outcast in 2007. Code followed with Resplendent Grotesque two years later.

…

…

During those four years, McNerney made some of the most forward-thinking and unsettling metal to come out of Norway. If you’re into theatrical and oddball metal music, these two albums are some of the best. The musicianship is excellent but so is McNerney. He alternates snarls with crooning, attacks each syllable and disregards the meter when necessary.

Resplendent Grotesque, in particular, shows him stepping outside the confines of what was and was not done in a black metal project at that time. “I remember thinking on that second Code album to kind of, I wanted to get more of a death metal edge to the vocals, get them a little bit more dimensions to them,” he said. “I was looking at a lot of different influences at that time. I was listening to a lot of different grindcore and crust punk bands. Severed Head of State, and World Burns to Death, and then also some of the classic death metal stuff—Martin Van Drunen was a big influence on the vocals.”

He lists one more left-field influence for that performance: Patti Smith “The Horses record was a big influence on the cleaner vocals, even though it probably doesn’t come across that way,” McNerney said, citing her “unbound aggression” as his key inspiration. “That record is such a good sort of landmark of where punk went to pop, but I don’t think she sacrificed any integrity, and that’s why she gets so much respect. She crossed over from being a punk to an artist who’s taken very seriously. But it’s also very pop. That’s something that you always, as an artist, you will strive to do. To be able to make a statement, make a point, but at the same time be taken seriously and not be a sellout.”

At the time there was an appetite for this kind of music—prog metal bands like Meshuggah and Mastodon were popular in the United States, while websites like avantgardemetal.com grew, and interest in black metal rekindled in the mainstream. McNerney did not cross over the way Smith did, though. Code rarely toured.

…

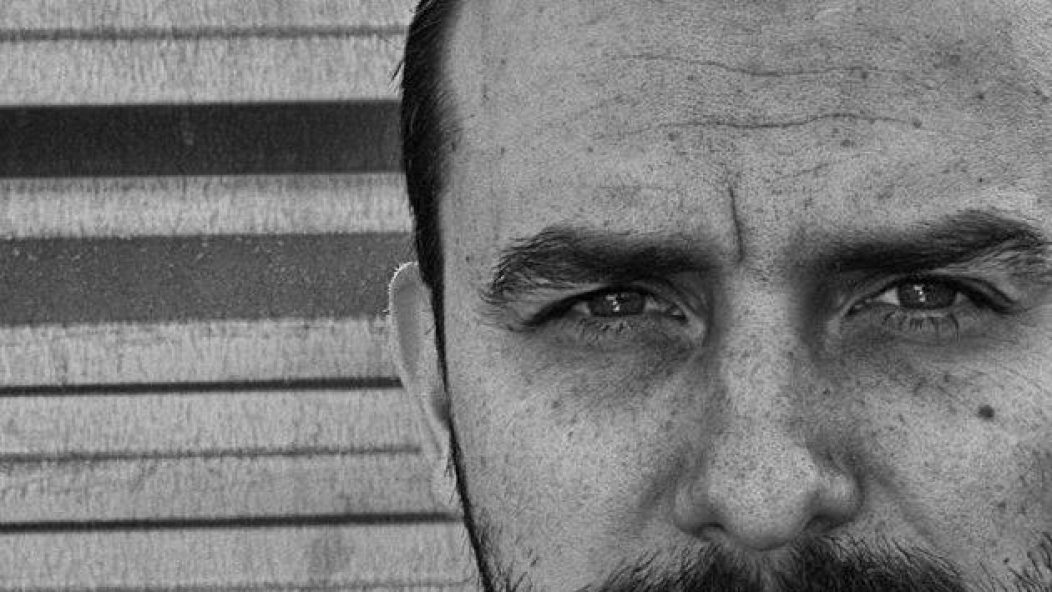

Photo by Head ov Metal

…

McNerney sounds downcast when he talks about that time. “I really feel like I was never really a success on the extreme vocal stuff. And that sort of led to me to stop being that so much […] I was in Dødheimsgard for a long time, maybe five years,” McNerney says, “and we only made one record. I wish we kind of got another one out. But actually, the best thing happened. Aldrahn came back. And they made a great new record. It’s one of my favorites of last year. […] Code just kind of petered out.” Code also released a new album last year, their second without McNerney.

For what it’s worth, McNerney doesn’t see himself going back to extreme metal. “Up until that time, there was still sort of ground to be made and still, you could still push some boundaries. But then I think the kind of avant-garde black metal scene, there really was a thing for it back then. There was this avantgardemetal.com. And there was kind of a scene, that the whole Jester Records, Ulver scene. But it kind of dissipated, I think.”

In the wake of leaving both bands, McNerney moved to Finland and almost immediately began making more accessible music. Like Smith, he tried to find the bridge between punk and pop music. He formed two bands, Beastmilk and Hexvessel, one of which would bring him into a new family, and the other which would very nearly bring him into the international music spotlight before self-destructing.

That half of the story next week.

—Twitter—@JosephPSchafer

—Instagram—@timesnewromancatholic

…

When We Are Death can be pre-ordered here.

…