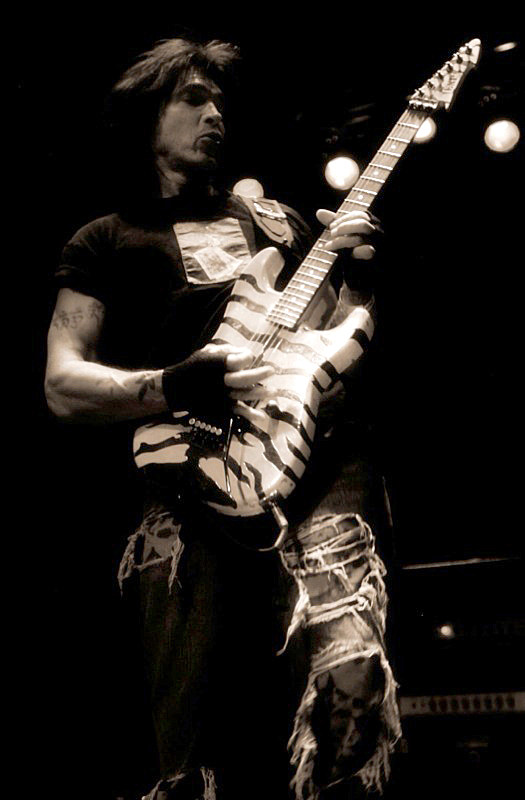

Kevin Hufnagel (Dysrhythmia) interviews George Lynch (Dokken, Lynch Mob)

. . .

A few months ago, Cosmo invited me to write an article about my discovery of heavy metal during the days of my youth. George Lynch and the music of Dokken were a big part of those days and my initial inspiration to pick up the guitar. Interviewing someone you grew up listening to from an early age is a bit more intimidating than perhaps talking to a more recent musical influence or a contemporary peer. However, I found Mr. Lynch to be an extremely humble and soft-spoken man, who, in this interview, recalls his own story of meeting an early childhood musical hero, reminding us that even our idols get butterflies meeting their own idols.

Other topics we touched upon include his interactive Guitar Dojo, earliest inspirations, his newest album Kill All Control, the trials and tribulations of being in Dokken, auditioning for Ozzy Osbourne, his love for improvisation, raising children in a musical household, and the constant quest for the world’s greatest guitar solo.

Dysrhythmia, Byla, Vaura, Gorguts

. . .

Kevin Hufnagel: So, I have about a million questions to ask you. I don’t know if we’ll be able to get to them all.

George Lynch: One million questions! This will be the longest interview I’ve ever done!

KH: Well, I think I have to get the fanboy stuff out of the way and tell you you were my initial guitar inspiration from when I was around 11 and saw the video for Dokken’s “In My Dreams” on MTV. That totally made me wanna run out and buy a guitar.

GL: Change your life?

KH: It really did. It’s sort of surreal to talk to you right now, so… just to get that out of the way first. (Laughs)

GL: Oh! I appreciate the appreciation.

. . .

Dokken – “In My Dreams”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3_NgBhgCec

. . .

KH: The first thing I want to talk about is your Guitar Dojo course, which you started around five years ago?

GL: Yeah, roughly.

KH: In some ways, I think that was a bit ahead of its time, because nowadays I see people offering lessons through things like Skype, but you were doing something like this before that.

GL: Well, for me it was a natural evolution beyond the traditional DVD lesson thing, which I think was kinda waning a bit, so, I thought, “This could use a new model”. Of course now, as you mentioned, through Skype or YouTube – I mean that’s what I do. I go on to YouTube for free and look up whoever it is I’m interested in learning from! (Laughs)

There’s all kinds of stuff there, so at that point I sort of dismantled the Dojo because I felt I either had to step up the game considerably or just let it go. I just didn’t have the time and resources to really invest in doing what I wanted to do, which was improving it in all areas and make it a much greater experience. It just required so much work for the time it needed to evolve into where I thought it should go. So, I had to step back.

It was a wonderful experience, though, for the five or so years I had it. The guitar players involved are sort of like friends. You got to know them, people were sharing music back and forth, they’d show up at shows. So, there was sort of this camaraderie there that was pretty fun. We had a seminar one year at the Los Angeles Sheraton ballroom, and people came from all over the country, and that was a great experience. It was really amazing. That was the highlight of the whole thing. In fact, I brought some people back to my house for dinner. (Laughs) It was a wonderful time. I still get some calls from people from that night, and I made some friends through that that I still stay in touch with.

KH: That’s the amazing thing about this day and age. Can you imagine taking lessons and having that sort of connection with someone like Hendrix?

GL: (Laughs)

KH: It’s just mind-blowing what can happen these days, in those respects.

GL: It was a different world at that time. You didn’t have Internet, and rock stars were real rock stars back then. People sold records back then!

KH: Maybe some of the mystery is gone in some ways?

GL: The mystique is gone to a certain extent, but some people maintain that mystique by design. But I’m kind of over that. I’m a working musician, you know? I mean, real world. I build guitars. I work on records – my records, other people’s records. I tour. I do a million other things. I wear 10 hats, and I love it! I’m not trying to be mysterious. I’m an open book.

. . .

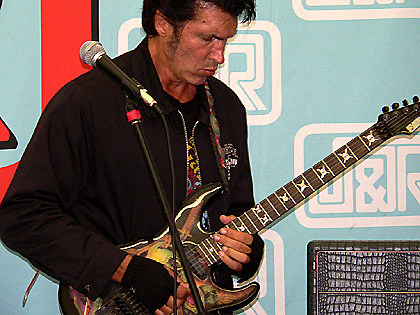

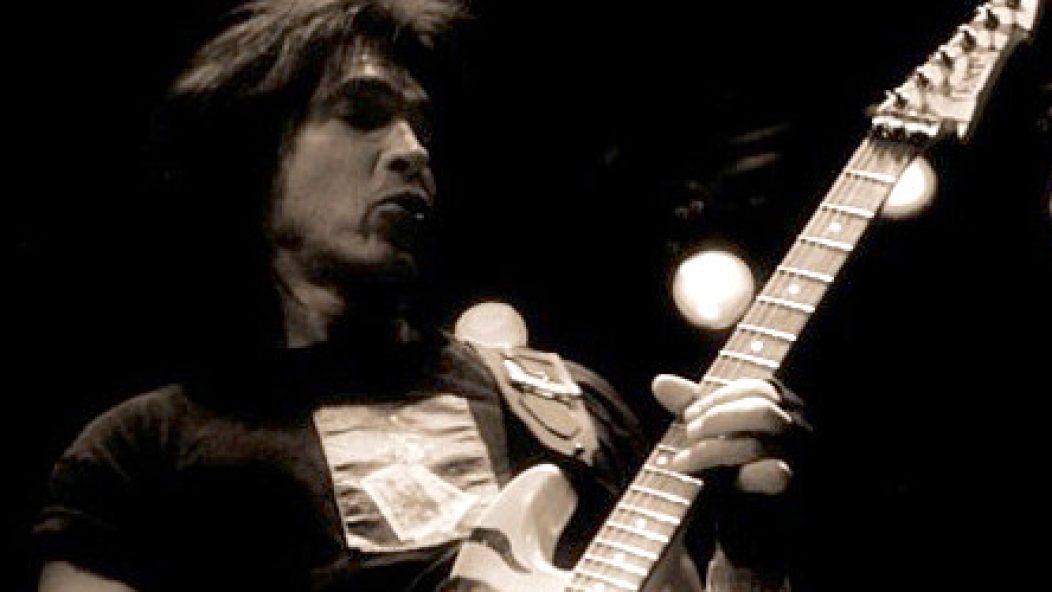

Photo by Live at J&R

. . .

KH: You were mainly a self-taught guitar player. Would you say you developed your style by ear, and by messing around on the neck, playing what sounded cool to you?

GL: Primarily, yeah. I mean, I did take lessons. I had one teacher in particular, Jim Taylor, when I was about 15. I’d ride my bike five miles once a week and show up an hour early and stay two hours late. We chilled after my lesson was over, and I just watched him play. He was very Clapton-esque in style. This was a long time ago. To me, he was like a god, to just see what he could do with this ’55 Goldtop. He had great vibrato, great feel, great chops. I was just like a sponge, and we’ve now become friends again.

KH: Oh, wow!

GL: He came out to a show, introduced himself, and now we stay in touch and everything.

KH: That’s great.

GL: It’s a beautiful thing. He comes to my shows, and I always call him out. I have a huge debt to him for a lot of my style. He inspired me to keep going. When you’re that age, and you have so many distractions – girls and friends and being a teenager, and all the things that are going on – I could’ve easily gotten sidetracked. He kept me on the straight and narrow, and kept me inspired.

. . .

KH: How often when you start an idea for song, does it actually get finished? Are you the kind of person where if you come up with an idea, you stick with it and finish the song? Or do you find sometimes ideas get forgotten, or you come back years later and finish it?

GL: Every time I pick up a guitar, I come up with an idea – as most of us do. I’ve gotten into the habit now of clicking on my iPhone demo thing and recording it, just so I can have it for prosperity, although I usually never refer back to it. But the way I write with the band – I don’t bring anything preconceived to the table. We walk in, plug in, jam – and that’s the way I’ve done it since I was a teenager. It never changed. Dokken. Lynch Mob. All the same. I’ll have a riff, and then that inspires another part, and then we might get stuck at the bridge, and everyone will put their heads together and try some different things, then keep working out the song over the next couple of days, or couple of weeks. This Kill All Control record, we wrote everything in 10 days.

KH: Yeah, I read about that.

GL: It was a lot of fun.

. . .

. . .

KH: Speaking of the new record, how did you come to choose the vocalists, because there’s a variety of guests. Were they people you went way back with? I know you’ve played with some of them already. And how did you choose which songs you wanted certain people for?

GL: It’s nothing like Santana or Slash, where I’m in a boardroom with my manager and record company and say, “OK, let’s fire out a plan and get the world’s greatest singers, get Rihanna, and Kid Rock and whoever else”. This was a self-funded record that I cared about and did with my friends, did very quickly, just kind of capturing the moment. Then we ran into the lead singer problem and then spent two years trying to fix that.

The whole record’s just a big, happy accident. There were people out there who I been wanting to play with in the past like Will Martin, or Keith St. John, who I know, and we’re friends. He’s a real hard worker and a great singer. He came in just to help me out. And Marq Tourien was a replacement singer for Oni [Logan, Lynch Mob] when he couldn’t go to Canada, and agreed to come in when Will went away, and work on a few songs. And then, at the end of the day, London [LeGrand] came back and got his shit together, and did a beautiful job. [It] literally brought me to tears when I heard it, and I’m so happy he’s back. He’s a good friend. I love him. We have a long history, and he sounds fantastic on the record, on the lead track “Wicked Witch”.

. . .

KH: I was wondering about the song “Son of Scary”. Was that based on live improvisations you did on the original “Mr. Scary”? Obviously, it’s based on the original song, but how did you approach writing that track?

GL: It was out of necessity from a business standpoint because I insisted on a kind of democratically built band in Dokken, which is why I had so many problems with Don. He wanted everything for himself. We split up all the songs equally, as well as everything else, and that song being one of them. Even though I actually wrote the whole thing, I divvied it up. What I didn’t understand back then was to do that, you had to give up control of the songs. Guitar Hero called me, and they wanted the song for Guitar Hero, and nobody had a problem with it except Don – just to spite me, deny me the satisfaction of having it on Guitar Hero. He made Guitar Hero‘s legal department very uncomfortable and inundated them with threats, lawsuits. So, I said OK, I’ll rewrite the song that I originally wrote. [I] did it on 7-string, and it turned out pretty good.

KH: So, is Guitar Hero going to use that track now?

GL: No. That’s the ultimate irony, is that after I was finally able to pull that off after two years or whatever, now I think they’re out of business. (Laughs) Which is why I put it on the record as a bonus track. I went through all of this, I gotta put it on something.

. . .

“Son of Scary”

[audio: GEORGELYNCH_SON.mp3]

. . .

KH: The Lost Anthology release has your old band Xciter on there, and I notice a number of those songs went on to become Dokken songs on much later albums, years after they were written.

GL: With some changes, yeah. A lot of that first Dokken record (Breaking the Chains) and even some of the second record (Tooth and Nail) were reworked Xciter songs.

KH: On Breaking the Chains, for the song “Paris Is Burning”, a live version was used, at least on the US release. I was wondering why the studio version wasn’t used?

GL: I was disappointed in the studio version. Breaking the Chains, despite the fact that we were just cuttin’ our teeth, there was a thing about it, when we were recording it, musically and instrumentally, that was really pretty cool, which you don’t get from the record now. It’s hard to describe. I had Rory Gallagher in the room. He was recording upstairs. I had the guys from The Scorpions come down. I recorded in the basement, and it had a 24-track, 2-inch tape machine, Telefunken tubes. Michael Wagener showed me how to run the board, and I just did my own guitar tracks. I didn’t want anybody in there, so I took a piece of plywood and nailed myself inside the room. (Laughs) Nobody was allowed in there. I’d work all day, and at night I’d have people come down, have a beer, and it was really hair-raising. I mean, when I had the guitars up, and then all the guitars in, and there were no vocals on there yet, it was pretty massive.

One of my musical regrets was that I trusted Don [while the rest of the band had returned home]. He had gone in and basically emasculated the record. He didn’t want the guitars loud. He washed everything out, put a bunch of effects on the master, and just killed it. It’s so hard to describe to people how cool it was when it was it originally how it was supposed to be. Much better sounding than Tooth and Nail. I mean I had Richie Blackmore’s old 100-watt cabinet. I had his Rangemaster treble booster. I had my old plexi heads. I had my EP-2 Echoplex and the old recording equipment I told you about, and Michael Wagener at the controls. We were creating a monster, and it was hair-raising, and then Don killed it. It’s one of my huge regrets. If I ever become a millionaire, I’ll go back and try to find the original tapes. It was a lot better-sounding than Tooth and Nail, especially guitar-wise.

KH: Does the label have those masters now or the original tapes?

GL: It was such a bad deal. It was done in Germany with some French label with a German publisher. Don sold the deal as himself, not as the band, and it was based on two songs, which I wrote, “Paris Is Burning” and one other one. He called me up one day and said, “Hey, I’m putting a band together. I’d like to record these two songs. Can I work something out with you?” I said, “Sure”. He never showed up. He went to Germany. He signed a deal for the first $5,000 or whatever, saying that he wrote those songs. They were based on those two songs, that publishing deal. He took the money, spent it all, and kept it forever. I found out about it a year later after I joined the band. I insisted on seeing this documentation our deal was based on, flipped to the last page and see that Don had written his signature, saying that he owned the songs, and he got all the money. You know? (Laughs) And then I realized who I was in a band with.

KH: I remember reading about all the tension between the two of you throughout the existence of your time in the band. I never knew the whole story, but it seems it got off to a bad start right from the beginning.

GL: Well, I mean, I didn’t do anything wrong!

KH: Yeah, I don’t mean with you!

GL: And our history beyond that was an extension of that – and how he behaved, his sense of entitlement. It’s all about him, and everybody else should just pick the crumbs off of his table, if they’re lucky. He’s very talented at procuring other people’s talent and taking credit for it. That’s all that friction was ever about. No creative friction. If anything, it was personal friction. He wanted it all, and I thought we should all share.

. . .

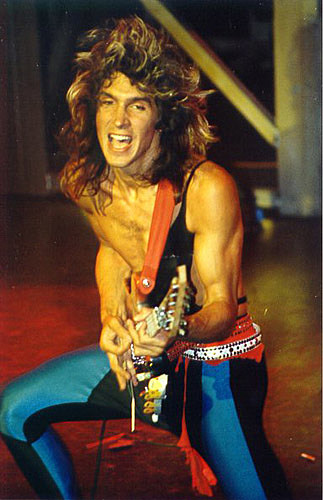

George Lynch, 1986

. . .

KH: One thing I remember hearing about, but never in detail, was your audition for Ozzy Osbourne. Tell me a bit about that.

GL: Yeah, I was up for it three times. The one time that was most serious, they called me in for an audition and flew me out with their publicist. I had done a demo tape for them, and they liked me and brought to me to England. I worked for the band a little bit, sat in the wing during soundcheck, but never played any performances with them. Brad Gillis was playing guitar at the time. It was pretty intimidating for as young as I was and inexperienced as I was back then.

I think [drummer] Tommy Aldridge had something to do with me not being in the band. He felt the chemistry was low, and I was a little green behind the ears, and I wasn’t ready. We talked about this when we did a tour with Lynch Mob a couple summers ago. He’s a sweet guy. and he explained to me it wouldn’t have been right because I’m the kind of guitar player that could really build a band around me. He’s right, you know? I don’t make a good hired gun. You don’t wanna invite me to your campfire. I don’t know any cover tunes. I don’t fit well in other people’s tunes. I just like writing my own tunes.

KH: I totally understand that.

GL: So they wanted to audition one other guy, but they said “You’re in, you’re in. It’s all good”. They offered me $200 a week, which was the starting salary. That kind of blew me away. I quit my job as a truck driver and had two kids living in an apartment, and ended up losing my apartment over this, because I spent a month doing these auditions, and I never made a nickel. I had to go on the food stamps and try and find a new job. That was kind of heartbreaking.

Ozzy was like “Well, Wendy Dio wants to check out this one other guy. We promised her we would as a favor. We’re sure you’re the guy, we just wanna check him out.” So I went to S.I.R., and Jake E. Lee was up there. He didn’t play very well. and he admits that, but he looked fantastic. Dressed in leather head-to-toe, long hair down to his ass, looked the rock star. I at the time had cut my hair because I was driving a truck in South Central Los Angeles delivering liquor, and I didn’t look like a rock star. Ozzy had a problem with that. He came into my room and said… I mean, I could hardly understand him, but from what I could make out of what he was asking, he said “Why did you cut your hair?” Which I thought was kind of ironic at the time, because that’s when he shaved his head and was bald.

KH: Right! (Laughs)

GL: (Laughs) Hey dude, I’ll wear a fuckin’ wig, whatever it takes! Never got that chance.

. . .

KH: I was wondering if you ever hear music in your dreams and turn them into songs?

GL: Well, I’ll tell you, I get a lot of ideas when I’m going to sleep or waking up. I really should have a recorder by my bedside, so I could just talk the ideas in the recorder, and hopefully be able to translate the ideas later, but I usually never do. Then sometimes I’ll be on the road and I’ll have this whole thing go through my head that lasts an HOUR. (Laughs) And if I could just plug something into the side of my brain and I could remember it, this would be the world’s greatest song, the world’s greatest jam, like Band of Gypsys, but like right NOW, you know? I’ll always have this world’s greatest guitar solo going on in my head that I’m always chasing, but I never get there. Yeah, it happens a lot. Keeps you motivated, never quite getting there.

. . .

KH: Would you say you’ve met most of your living musical idols? Have you ever been surprised by someone that’s come to you and considered you to be a major influence on them, maybe from a different genre or something?

GL: It does surprise me that I run into a lot of metal guys, like extreme metal, you know? Jeff Loomis (Nevermore) was the most recent guy. We’ll write each other now and then. He’s a great guy, but I don’t get it. I don’t play anything like that. I wish I could. It’s an honor – the recognition and respect. But, I don’t quite get where I would’ve had anything to do with their appreciation for what I’ve done. Still, it’s wonderful to be appreciated.

On the other hand, when I’ve met a few of my idols, that’s been pretty intimidating. The biggest one being Jeff Beck. When I did the first Crossroads event, I went to the backstage area and I saw him. I said “Oh my God. I may never get the chance again”. The first record I ever bought with my lawn-mowing money at the mom-and-pop music shop in 1968 was Truth. I wore that out, and there he was. I had to go up there and bug him. I felt bad.I don’t want to ever be “that guy”, you know? I got tongue-tied and didn’t know what to say, because I was so nervous. I hate to admit this in an interview, but I got weepy-eyed meeting him because it was such a powerful experience for me to meet this guy.

KH: Of course.

GL: A giant in my life as far as musical influences go. I really didn’t know what to say, but he was a gentleman, really sweet. I wanted to ask him a million questions, and as soon as I left I started thinking “Oh, I should’ve asked him this, or that”. Kicking myself! Then, when I was much younger, I met Richie Blackmore. My friend in my band, we went up to Hollywood. Took the bus there, trolling Hollywood Blvd. This is like the early 70’s or something, and Blackmore was at, I believe, The Rainbow, or somewhere on The Strip. So, there’s Richie Blackmore. Oh, my God. We were all nervous. We wanted to go up to him, but we were scared. Finally, I was the one picked to go up to him, and he was with some other guy, maybe from Deep Purple? They weren’t really nice to us. We were kind of hurt by that. But then he came over and sat with us, and that was a pretty awesome moment.

KH: He was kind of rude at first, but then came and hung out for a moment?

GL: Yeah. And now that I’m in the guitar world, that’s what I do, I get opportunities to talk to all these guys that were massive influences. A photographer buddy of mine, Rick Gould, said, “Listen, you gotta go with me out to the Mojave on this certain day”. I was like, “I can’t, I’m busy, I have something going on, I can’t change it”. He said, “Trust me, you have to go”. I just kept insisting I couldn’t. Finally he said, “I didn’t wanna tell you, but I’m bringing Billy Gibbons”. So, Billy Gibbons and him pull up in my driveway, and we drive out to the Mojave. It snowed that day in the desert. We stopped at a little Mexican restaurant, had a few beers and some Mexican food. We go back to my house, go to my studio, hang out with my family. My little girl, who was eight years old at the time, runs out and gives him the “How how how” (from ZZ Top’s “La Grange”) thing.

KH: (Laughs)

GL: It was surreal and beautiful. It was just a wonderful time, and of course I thought he was gonna be my best friend after that, but he never called me back.

. . .

George Lynch guitar lesson

Rotating Harmonics

. . .

KH: One thing I’ve been thinking about lately, and I wonder if you ever do, too, is what your playing will sound like 20 or 30 years from now? Do you ever wish you could have a recording of that right now and hear what it would sound like? Or maybe the day your hands don’t work anymore, hear what kind of music you’d be making with the guitar at that point?

GL: I don’t care if my hands work in the future, as long as my glands work, you know what I’m saying? You know, that concept has never entered my mind. I would imagine my abilities would diminish somewhat, but maybe not. I always vowed to be that guy whose abilities and fire continue to burn in my belly. So many of my heroes like Clapton and other guys became billionaires and superstars. But the Clapton I loved was Cream. I don’t like the old man that looks like a shoe salesman or an insurance salesman playing mediocre, thin-sounding guitar over a bunch of blues songs he stole. I wanna hear the guy with Ginger Baker playing jungle drums like an animal, with old plexis with an ES-335 at Royal Albert Hall. And [Jeff] Beck is the exception. He’s continued to evolve in unexpected ways and get better and better with age. Hopefully that’s the model that I can follow. I mean, I’m not trying to be Jeff Beck, but you know what I’m saying. That’s why I’ll always go different places.

I don’t how many people are aware of my more recent catalog, because it hasn’t sold as well, but, people sort of look at me as this 80’s guy. I haven’t done that since the 80’s. That would be the hardest thing for me to do now. I’m gonna do a blues record, this real kind of roots record with just a box and a slide guitar. I’ve done a rap-metal thing. I’ve done progressive stuff, I do heavier stuff like the Kill All Control record – not heavy heavy, but heavier than what I’m known for – and jam music. I grew up being a jam guitar player. I still do that. I’m really into jam bands. But to me, most of them are not true jam bands. It’s not true improv; a lot of [it] is songs, like Gov’t Mule or Phish or whatever.

There are jam elements to it, and I thought that would be cool, so I’m doing a documentary called Shadow Train for The Documentary Channel. I’ve already started on it. We’re going to finish production on it next spring. We’re getting some guest artists involved. It’s Native American music-based. We have a core band called Shadow Train. We travel around in an old ’60s station wagon with a horse trailer, a generator, solar panel, and visit all the Native American reservations from the Southwest to the Dakotas and share the music, playing with the Native Americans at historically significant places like Pine Ridge and Wounded Knee, and use the music to kind of tell the story, the history, the sad story of the plight of the indigenous people – the point being that the music is all improvised. We’re gonna have Flea, who does acid jazz with a trumpet through a fuzz tone, Serj from System of a Down, Tom from Rage Against the Machine, Robbie Robertson, who’s 100% Native and does records like that, getting involved. But it’s all improv music. True improv, in that we react to the environment.

KH: Totally free improv?

GL: Absolutely. It’s kind of like being a high wire act, and people experience the creative moment ,versus the re-creative moment – which I think is very important. It’s like being in the front row of Band of Gypsys or something. (Laughs)

. . .

KH: You mentioned you have children. Do any of them play music?

GL: They’ve all dabbled to a certain extent. Nothing too serious. My oldest son was the most serious, and he was my guitar tech for awhile in Dokken for one tour. He went to GIT for probably a year and a half. But I think it’s important that our kids, any kids, have access to music, because it does a lot of good things. It enhances learning development. It’s kind of like the serious universal language. We have musical equipment all around the house. A drum set, keyboards, guitars, bass, amps, a recording studio, piano, and all that stuff. It’s all there.

KH: But you don’t force it upon them.

GL: I wouldn’t wish this occupation upon my worst enemy.

KH: (Laughs)

GL: (Laughs) I always steer my kids in the opposite direction. My oldest son went back to college, and he’s a chemical engineer and got his degree and works for Siemens Corporation now sequestering C02 gases out of coal-fired energy plants. He’s doing good work!

KH: Awesome. Well, that’s all we have time for. Thanks, George.

GL: No problem. When you ask me a question, I give you answers to three more questions.

. . .

George Lynch ESP signature guitar

. . .