Iron Maiden's 'Somewhere in Time' Turns 30

…

We teach the history of ancient civilizations to children in elementary school for two reasons. First, because much of Western culture still builds from texts such as the work of Plato or Hammurabi’s Code. Second, young people occasionally find antiquity interesting because it is a sign that the world was not always the way it is now. Dinosaur bones capture the imagination the same way. You can look at a piece of the great pyramid of Egypt, or the crooked edges a Tyrannosaurus skull where once flesh or mortar connected but are now gone, and your imagination can fill in the blanks. But at the same time, you know you will ever see a dinosaur, and never visit the pyramids in their height of glory and completion.

As befits its title, Iron Maiden’s Somewhere in Time album gives me the same feeling. It was released only 30 years ago today, but already much of this album has been lost to history. Even though it was released at the height of Maiden’s popularity it’s a forgotten album – not by the fans, who fetishize every cultural artifact the band generated during the 80s, but by the members of Iron Maiden themselves.

Iron Maiden recorded Somewhere in Time in the aftermath of monumental occasions for the band: the release of six albums in as many years, counting Live After Death, the yearlong World Slavery Tour and, for the first time in the band’s history, a six-month long break. Well, six for some, four for those members who couldn’t keep away from writing new songs.

Given that, it’s easy to see the first half of the band’s career, including original singer Di’Anno’s replacement with fan-favorite singer Bruce Dickinson, as one long uninterrupted period of activity, which may account for the sonic cohesion between those albums. Sure, Powerslave sounds better than their self-titled record, and the singer switch made a dramatic impact on their songwriting, but overall the classic Maiden material all sounds of a piece.

But with that break came introspection and with introspection almost always comes change. Somewhere in Time sounds different, for the first time in Maiden’s career.

The most obvious difference in sound involves the use of guitar synthesizers, new technology the band experimented with during the touring break after tourmates and forerunners Judas Priest tinkered with the same sound earlier that year. But where Priest stuck with the technology for at least one more record, Maiden dropped them in favor of studio keyboards later, isolating that sound on Somewhere in Time. The guitar synths give the album its own identity, but also maroon it in Maiden’s discography. For a great example of that technology, listen to the title track.

…

…

The most indelible song on Somewhere in Time is the intro to both the best song on the record, and probably the most commercial song in the band’s career: “Wasted Years.”

“Wasted Years,” written by guitarist Adrian Smith, is one of the only songs Maiden still plays from this record. The opening bars of that song cut with the precision of a surgical scalpel, but remain instantly recognizable. That intro, tacked onto the end of a demo tape, caught the ear of bandleader and main songwriter Steve Harris, who wound up including two more Smith songs on the record: the swaggering and awesome “Stranger in a Strange Land” and a somewhat bloated number called “Sea of Madness.” Smith only holds three writing credits on one earlier Maiden record, Number of the Beast, but all of those songs were collaborations. Here, his contributions rival Harris’s: He even sings lead on the album B-side, “Reach Out.” Somewhere in Time is Smith’s record.

Which leads us to a question: Why was Harris digging through Smith’s demo tapes anyway?

Harris opted for Smith’s half-formed but futuristic view of Maiden’s future because he could not accept the alternative presented by Bruce Dickinson.

During that six month break, Dickinson opted to write alone, instead of alongside Smith, and came up with a series of semi-acoustic songs which the band rejected. Dickinson’s vision of Maiden’s future resembled the arty turn Led Zeppelin took on IV and Physical Graffiti. When that vision was rejected, by some accounts Dickinson fell into a bout of depression and nearly left the band. Dickinson didn’t write a song alone on an Iron Maiden again LP until 1990’s “Bring Your Daughter to the Slaughter.”

Without Dickinson’s input, Iron Maiden crafted an ambitious album that, unfortunately, sounded dated on delivery. The first two songs on the record are among their best, but the ho-hum “Sea of Madness” and the incredibly irritating “Heaven Can Wait” close out side A in turgid fashion.

“Heaven Can Wait” in particular highlights Harris’ weaknesses as a songwriter. The chorus is repetitive and shrill, barely interspersed by awkward mushmouth verses. A decent bridge that, admittedly, makes the song pop when played live also stretches this slog out to seven and a half minutes.

That shit doesn’t fly less than a year after Metallica release Master of Puppets and one week before Slayer release Reign in Blood.

…

…

Side B, though, offers a rare glimpse into a moody and more sophisticated Maiden. “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner” simmers and vamps for six and a half minutes – it’s almost post-metal. “Stranger in a Strange Land” both stomps and satisfies, and “Deja Vu,” the album’s sole Dave Murray tune, is as strong of a single as its successor in “The Evil That Men Do.” Closing epic “Alexander the Great” can’t live up to the imaginative sprawl of “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” but then again, what can?

Maiden wound up rejecting Smith’s future as well. On the supporting Somewhere on Tour dates, the band drew more on their back catalog than on Somewhere in Time. They played “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner” once – on the first date of the tour – then dropped it. “Alexander the Great” wasn’t added to the set list at all. Ever. Iron Maiden play fewer songs from Somewhere in Time than from any of their other 80s albums, and according to Setlist.Fm the lion’s share of those plays come from “Wasted Years” and “Heaven Can Wait”. A shame, since ”Stranger in a Strange Land” and “Deja Vu” deserve more recognition. Nor did the band choose to record many shows from that supporting tour – possibly due to an inflating Eddie, which Harris and Dickinson were meant to climb atop while performing, which sometimes did not work properly. Once a stage lamp burned through the prop, causing one hand to deflate while Harris was standing in it.

…

…

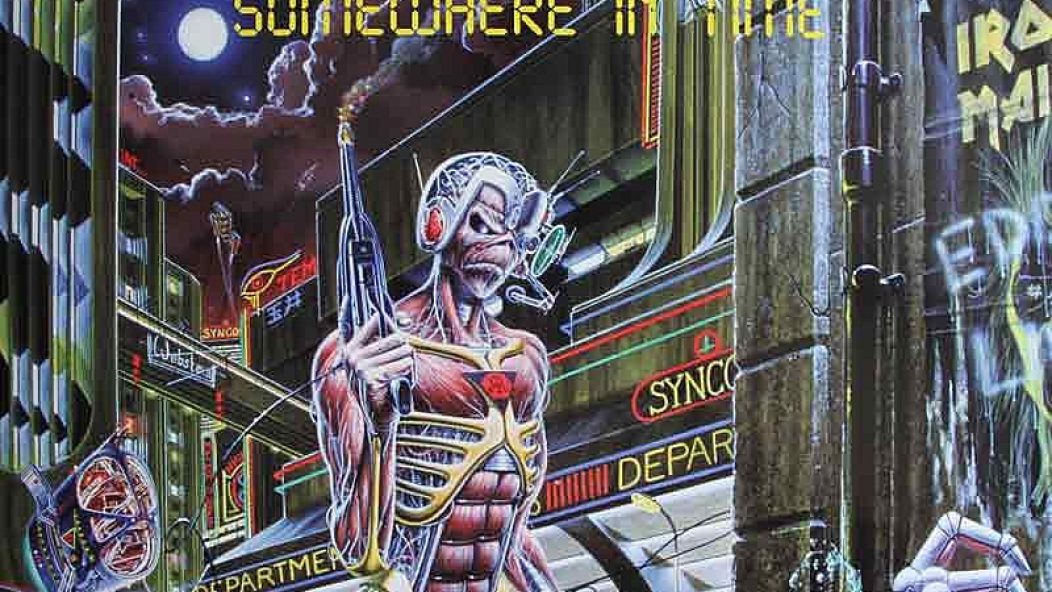

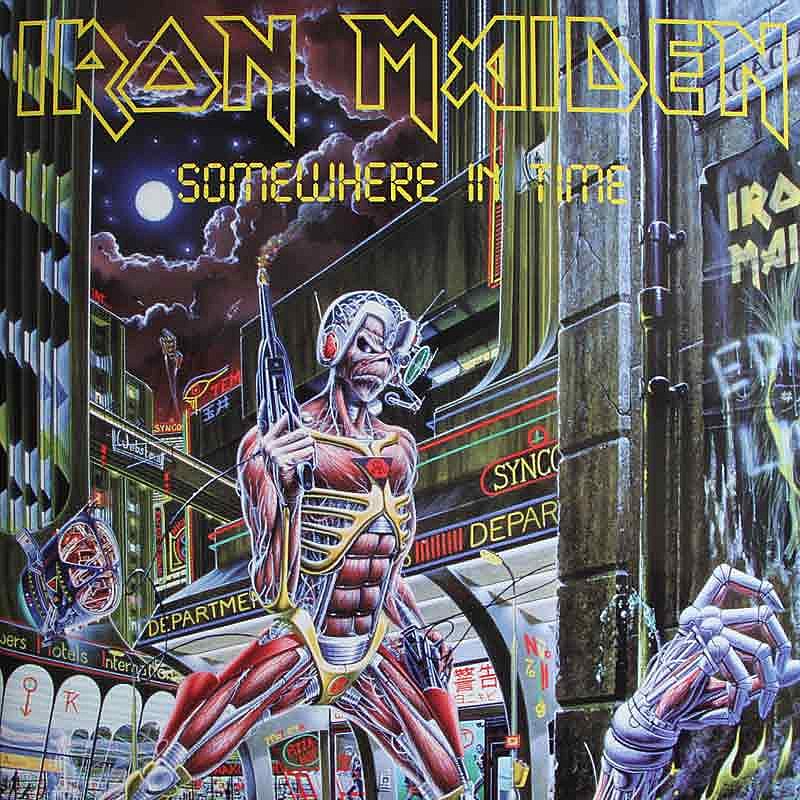

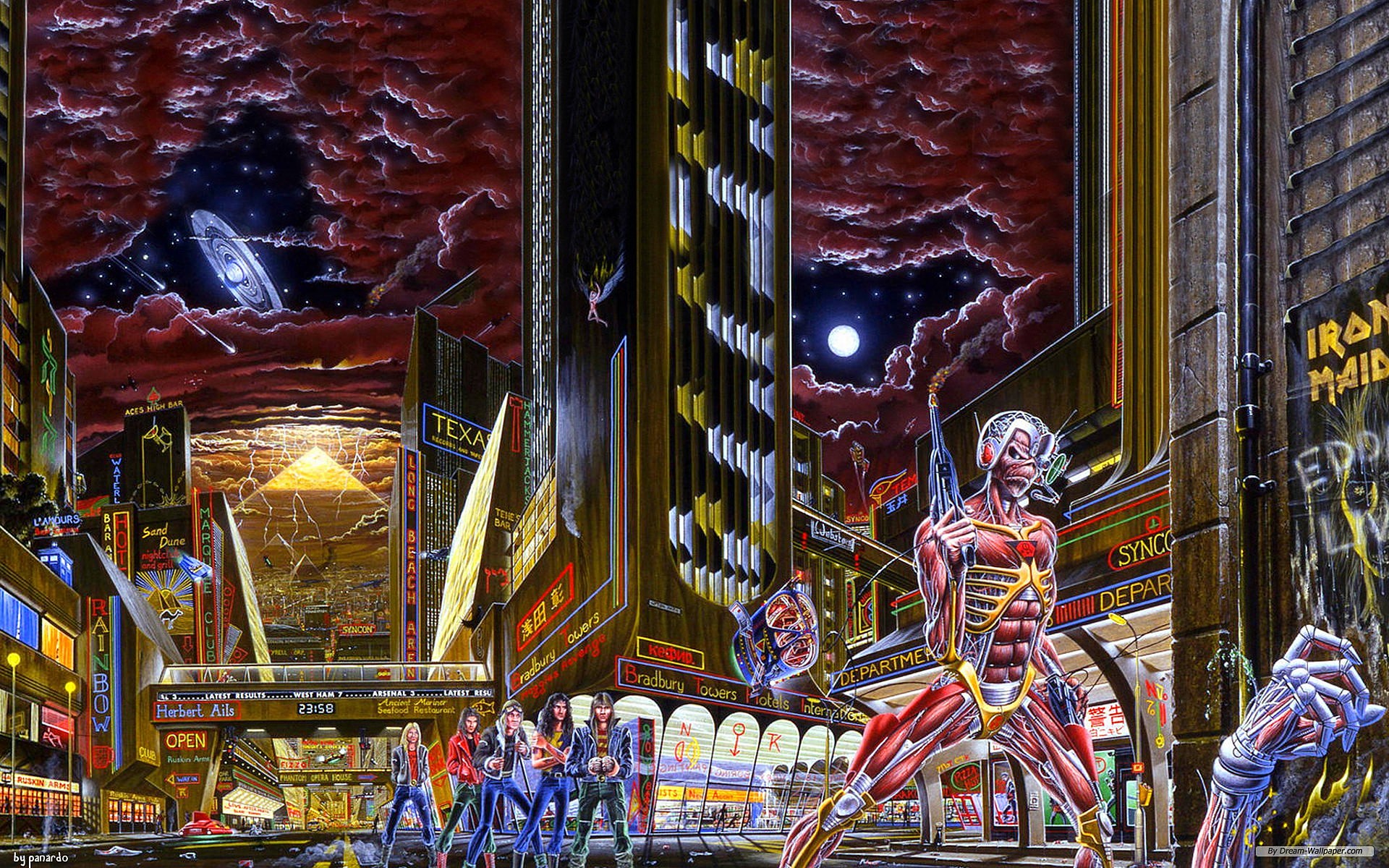

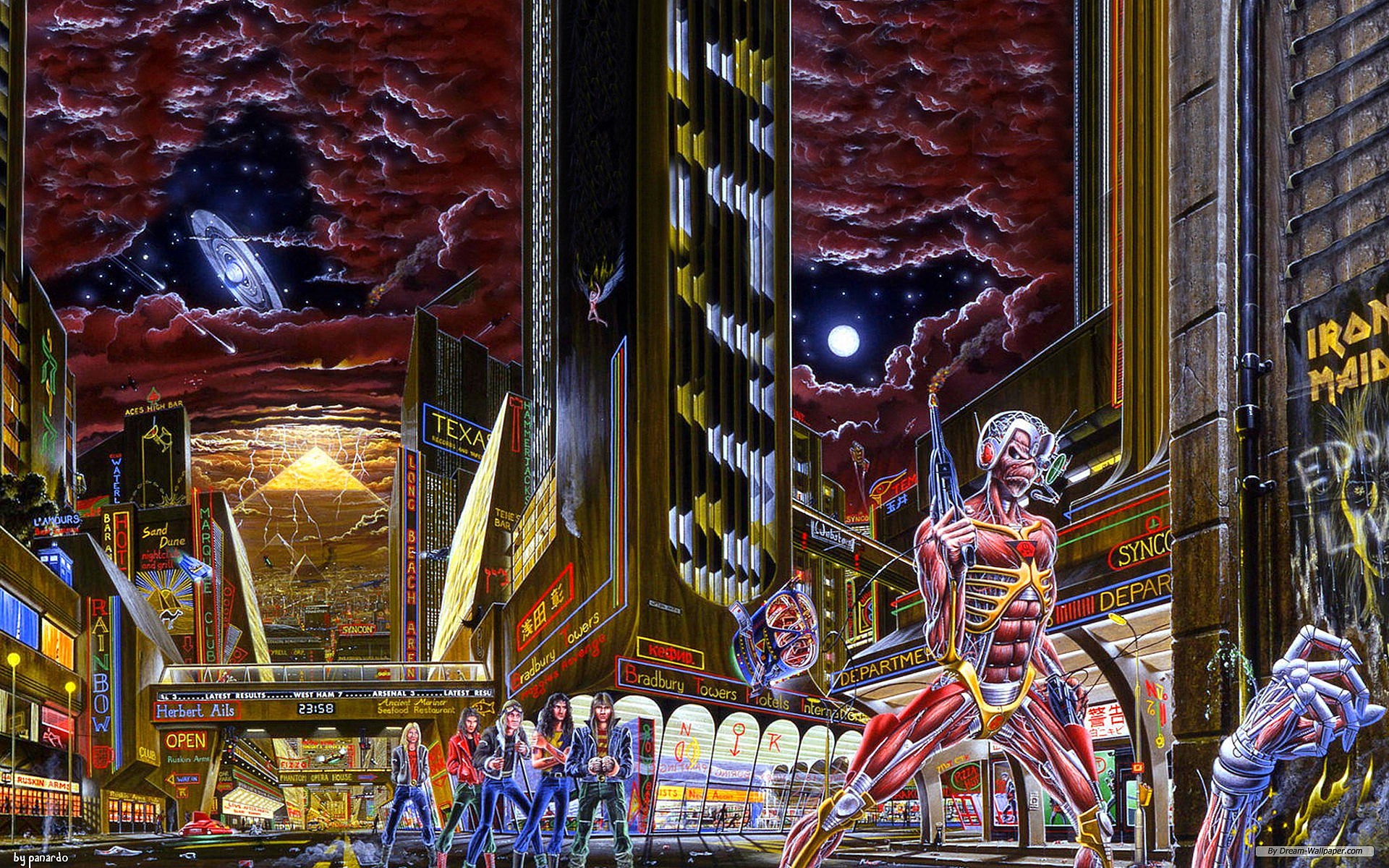

The songs may remain under-appreciated, but the Somewhere in Time artwork, at least, has its fair share of loyal adherents. Longtime Maiden artist Derek Riggs composed an imaginative and detailed cover that took influence form, and expanded upon, the uneven science fiction theme running through the album. The towering ‘Terminator’-esque Eddy standing ready to kill and a ‘Blade Runner’-ish background accurately predicted which pop culture signifiers of the 80s would resonate long past Thatcher and Reagan left office. At the same time, Riggs included a cornucopia of references to Maiden trivia in the artwork’s detailed background. The bounty hunter Eddie remains my personal favorite, and Riggs seemed to like it too: He included the same design on the Wasted Years and Stranger in a Strange land single covers. As a triptych, the three covers tell a rough narrative that both enriches and reflects the music they promote. Somewhere in Time isn’t Maiden’s finest suite of songs, but it may be one of the finest examples of album-as-art-package in not only metal but pop culture at large.

It’s sad, then, that Iron Maiden continue to ignore Somewhere in Time. As a project the album attempted to carry the band into the future while flexing a budding songwriter in Smith and appeasing a stir-crazy Dickinson at the same time. It accomplished none of those things: Maiden abandoned this sound, Smith hasn’t written so much at once since, and both he and Dickinson wound up leaving later.

That Smith and Dickinson since returned to the fold doesn’t alter the album’s significance as a harbinger of the end, not the end of Iron Maiden, but of the NWOBHM.

In 1986, with the release of Somewhere in Time and Turbo, the pillars of British hard rock attempted to embrace new technology, but sacrificed a piece of their identity in the process. British metal was made by steel workers and pubgoers, not by keyboard technicians. While that adaptation didn’t kill off their songwriting, it does look like a half measure in the face of the rising power of Californian thrash. Bookended by Slayer and Metallica’s most-beloved performances, Somewhere in Time closed the book on the golden age of British heavy metal.

…

…

…