Interview - Adam Zaars & Jonathan Hultén (Tribulation)

…

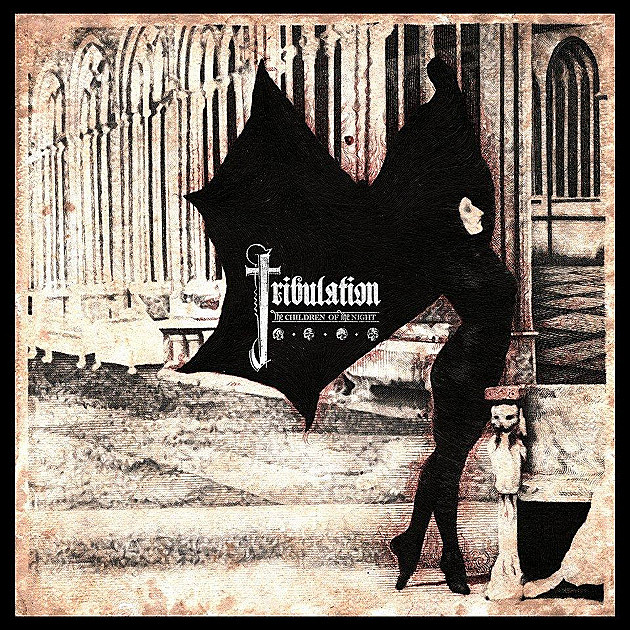

According to the informal readers poll at the end of my Top Albums of 2015 list, Tribulation’s Children of the Night is the best album of last year according to Invisible Oranges readers. It’s a solid choice. The Stockholm four-piece has done more to return classic rock-style melody and songwriting to extreme metal, so much so that in my review I said

“The Children of the Night offers a more fully-realized glimpse into what a modern extreme metal zeitgeist without the telltale signs of extreme metal today might look like. It is black metal without Mayhem or Darkthrone, but still with 30 years of accumulated acumen behind it.”

With that review in mind, I sat backstage with Adam Zaars and Jonathan Hultén, who play guitar in Tribulation, on the Seattle date of their 2015 tour with Deafheaven. We spoke about their love of horror, and how they make their music seem so instantly ‘classic.’

—Twitter – @JosephPSchafer

…

…

This is definitely the most hyped tour you guys have ever done in the United States. Have you noticed the difference from, I think the last time you were here you were opening for Behemoth and Cannibal Corpse?

Adam: Yeah, I mean there is a difference. I guess, the biggest difference is that, I think, most of the people who are here, haven’t seen us before. You can tell.

How?

Adam: Which is why we’re here, of course. That’s a positive thing. And they seem to like it. That’s the biggest difference, I think.

Jonathan: And it’s a different crowd than we’re used to. I mean, it’s not the typical Cannibal Corpse crowd who are going to the shows.

When I saw Ghost last night, Papa Emeritus said “we want to sound old.” But no one says “Okay. Let’s go back in time to 1980 and then forward down a different path back to 2015. And see ‘Okay, what does that sound like if history was just different?’” When I heard The Children of the Night I thought of it as an alternate history. Where was your mindset in terms of history and where you were going with making it?

Jonathan: I recognize that way of thinking. I had a similar idea a couple of years ago when we were writing the first album [The Horror] and the first Stench album as well. And I thought that it would be like picking up where the genre had been at ’90-something.

Adam: That was the case, especially with the first one. I think I actually said it in interviews as well back then, that it was sort of like going back to, I don’t know, like ’93, maybe. Before everything turned to shit in death metal, you know? And sort of trying to push it into the right track. But we’re not there anymore. I wouldn’t say we’re playing death metal at all now.

I wouldn’t, either.

Adam: No. So, I mean, we’re doing something else, still.

…

…

When you think about what you’re doing, what’s your thought pattern?

Jonathan: It’s easier to use metaphors, I think.

Use a metaphor, that’s fine.

Adam: Do you have one?

Jonathan: Yeah. You could use a word like poetry, and just say that what we’re doing is expressing ourselves. And it’s like, just, let it flow out of ourselves. And just keep pushing forward and do it with grace, if possible.

Adam: Very much so, I agree. If we’re striving for something, it’s not that we’re planning anything. It’s kind of the opposite. So if we’re striving for something, it’s striving for intuition, rather than . . . I don’t know. We try not to analyze what we’re doing that much. At least for us, it feels like we would end up in a different place if we did. And I’m not sure if that place is a better one, I think it’s a worse one. So I think we’re striving for some kind of seclusion. Because we try not to get too disturbed or entranced about what’s going on around us. It’s inevitable to some extent, but striving for that and intuition. Whatever happens, happens. Flow, like Jonathan said. And I think, in retrospect, we can always see what we did, but we really try to not think about that, while it happens. When we create, to just let it go.

Grace. I like that. That’s an apt self-assessment. When I started listening to extreme music, it wasn’t popular, and the new stuff was not considered good. People who are older than I was, they were very averse to melody, and they were very averse to emotion. Like, I remember I loved the Carcass’s song “No Love Lost.” I had friend of mine, sort of talk down to me and say, like, “What are you doing? It’s all melodic and they’re talking about their feelings. You suck. Throw that thing away.” I didn’t, of course. I’m glad I didn’t. But with you, I do hear those elements in the music.

Jonathan: I think it’s because of what we grew up listening to, which isn’t necessarily only extreme metal bands, that’s never been the only influence. Not even on the first one. We were inspired by movie scores, mostly horror soundtracks. Even Nintendo games. Whatever got us into the right feeling. And even when you hear the first album, it’s been a while since I listened to it, to be honest, but even when you, or we, think back to that era, it’s still a lot of feeling. A lot of striving for a certain atmosphere, rather than just… I mean, it’s a very fast, in-your-face album, but it also contains something else. You can sort of see where we were about to go afterwards, I think, in that one.

Adam: Yeah, and the form that was recorded—I mean the genre in which it took place—had been a bit limiting. And we needed to break through, to break loose.

…

…

It’s interesting that you mentioned movies. The album art for The Children of the Night is the re-issued poster for Les Vampires, the French serial. That struck me as interesting, because that’s horror but it’s not like your modern American slasher film. Even someone who considers himself or herself a horror buff may not have seen something like Les Vampires.

Adam: No. It’s not really a horror movie.

Not in the normal way but it’s horrific the way Hitchcock is. It’s dark, it’s a thriller. It’s gothic, and German expressionism. And your tour poster’s got the original Nosferatu on it, obviously. So why German expressionist cinema? Why silent cinema for a band that makes music?

Adam: That’s also been there from the beginning and I think the answer’s the same now that it was back then. It’s basically capturing a feeling, capturing an atmosphere that’s contained in . . . I mean, it can be a movie, but it can be a photo, a painting, whatever. And that’s it, really. It’s got to do with transferring that feeling, or that emotion, or that atmosphere into music. And, I guess, not only music, because also the imagery is always present as well. But that’s to make it whole, I guess. Even when you mention the album cover, it’s not really that we’re paying tribute to that series, to that movie. It’s rather just a perfect image for the sound of the album.

It is a fitting picture. It’s dark, and that character is feminine. And there’s a femininity to her posturing.

Adam: Grace, again.

Grace, yeah. That character is a ballerina, as I recall.

Adam: She is.

…

…

I was listening to the record with my girlfriend, she’s a big cinephile too, and she looked on the iPod and says, “‘Melancholia.’ Is that the Lars von Trier movie?” And I said, “I don’t know. I’ll ask.”

Adam: Well, no, it’s not.

It’s not, okay.

Adam: It is a good movie. But it’s not that.

But why the feeling of melancholy, as opposed to aggression, then? Because I think your music has gotten, perhaps, a bit less aggressive.

Jonathan: Oh, yeah, that’s very true. Why? Yeah, good question. I don’t know.

Adam: It feels more relevant, perhaps.

Melancholy?

Adam: That’s maybe how we express ourselves now. How we feel.

Jonathan: It’s Tribulation, I think. It’s sort of meant to be like this, actually. I think it reflects us as persons a lot better than the aggression. I mean, when we did the horror, the first one…

Adam: I think it did work.

Jonathan: Yeah, it did work. We were younger, more aggressive, I guess, in that sense. And why did we choose to do that? I don’t know. Again, it’s about that intuitive thing.

Adam: Momentum.

Jonathan: We don’t really think about why we’re doing it, which is why this is a good question, I guess. Because we just, when it comes to Tribulation, we don’t think, we act. I think.

…

Photo by Ben Stas

…

Well, if you don’t mind me asking, here’s a question. The band’s called Tribulation, which implies sort of a struggle. And melancholy is itself sort of a struggle. What exactly are you struggling with?

Jonathan: We’re struggling with everything. We’re struggling with rules, and with everything. That’s always been a core of the band’s ideal, to break free from whatever is holding you down. Because I think it’s the only way to grow as a person. When you look at, I guess, the lyrics for the second album and for the new one, it’s got a lot to do with that, with tearing something down and building something new that’s more in line with you at the moment. And you gotta destroy something to do that. I think that’s why we’re always doing new stuff. Our albums don’t sound the same.

Adam: No, they don’t.

Jonathan: So that’s a part of the struggle.

Adam: I think of it also as a metaphor for life in general. Living itself is a struggle. And everything you do is, in some way, a struggle. It takes something to make something happen, to act. And whatever it is, holding this cup up, or doing a show tonight, is a struggle.

And that’s a good thing.

Adam: Yes.

Jonathan: I think it’s needed, to create.

Friction?

Jonathan: Yeah, that’s probably right. And I don’t really mean the stereotypical, struggling artist, as an alcoholic, or whatever. Well, not necessarily, at least. I wouldn’t say we’re depressed or anything like that. Actually, rather the opposite. But we don’t want to get cornered, I guess. And if we do, we break free of all of that. That’s what we’ve always done, I think.

…

Photo by Ben Stas

…

That’s what initially attracted me to the genre, to this kind of music. When you’re a teenager you get frustrated. “Ugh, rules.” I feel like most people start this sort of music when they’re teenagers, but many stop afterward. I didn’t, and I still struggle with—not necessarily the law, but—rules, even into my adulthood.

Jonathan: You create your own rules as well. Your own mental rules and your own ways of thinking, your own patterns. I mean, it’s a spiritual thing as well. I mean, spirituality is exactly that, it’s an inner struggle.

Adam: Yeah, inner struggle towards refining yourself. Not always, but where the body is the alchemical tool that you’re purifying. And I think, it’s the same thing with this. It goes hand-in-hand. This is a spiritual thing, I think, what we’re doing is not necessarily about breaking the law, but it’s about finding out new ways.

Jonathan: Novelty.

Adam: Yeah, exactly. There we go.

Jonathan: Melancholy again. I think, to give you a more simple answer, We have it, in a way at least, from Sweden, and from . . . I don’t know if it’s in the soil or if it’s in the culture, but it’s . . .

Jonathan: We have the word: vemod. It’s present in our folk music and in our folklore, and in all of that. Which is an inspiration for myself and, I think, for all of us. The folklore and the folk music, especially. You can hear that in our music now. And it’s sort of melancholia. I mean, melancholy isn’t necessarily only a bad thing. It can be quite beautiful at the same time. And I think we’re doing that. I mean, we’re not a light band. I think we’re a very dark band, but I don’t think we’re ugly. I don’t think the music’s dark and ugly, it’s the opposite. I think we sort of find the gold in the mines.

Adam: I like that description of gold and mines.

I love words that don’t have an English translation. I’m half Brazilian, and there’s a word in Portuguese called “saudade,” and you can’t translate it into English. But it’s a similar sort of “pretty dark.” Nostalgia for a past that didn’t exist.

Jonathan: That’s closing in on where we’re going with the whole melancholy thing, for sure.

Here’s what I respect the most about Tribulation. It’s that the emotion of the lyrics and what is being said, and the construction of the music in a history of rock, history of heavy metal context are getting at the same idea from different ways. The container matches the contents, and a lot of bands have really struggled doing that. You almost need to stumble on it. It can’t be forced.

Jonathan: No, and again, we try not to think about that. We try to let it come to you instead, I think. Maybe that’s why it works. Or we hope that it works, at least.

Adam: Maybe if you start thinking about what you’re doing, why you’re running. If you start to be conscious about every moment that you do want to do that, you might not be able to run anymore.

Jonathan: But you’re always the best when you’re not. In sports, or whatever, when you all of a sudden you just manage to do something, you have no idea why and how. It just happens. It’s momentum, I guess.

Spontaneity maybe?

Jonathan: Maybe not.

Adam: I don’t think our music is spontaneous, in that sense, at least not the way I do it. Because the way I do it is, I collect and write, and then make songs out of it. I mean the material, melodies or beats, or whatever. You gotta have a certain period of just that, of just writing, I’d say, before we can do anything with it. So it’s not spontaneous for me, at least.

Jonathan: Collect, then you let it write itself.

Adam: We were talking about, some days ago, that these songs, they actually keep evolving while we’re playing them live. Because we start doing things that aren’t in the record because it feels right.

Jonathan: Music is live, it’s living. I don’t know if we get bored. It’s the same thing with the music. That might have something to do with the constant change, I guess. Gotta keep moving.

Adam: Yeah, I like when there’s a certain amount of improvisation, both in the music and especially live.

It seems like in metal in particular, in rock music too, but in metal in particular, not a lot of people do improvisation. But there was a time where that was a central part of the live experience. You didn’t expect Led Zeppelin to play the song how it sounded on the record. That’s sort of a new thing.

Jonathan: I think people got tired of it. I think, along with all the technological change, I think the attention span, in general, has become shorter. So I don’t think people have time to listen to a three hour jam.

Adam: At least they don’t consider themselves having time.

Jonathan: Yeah, of course, people do have time. But people would get tired of holding their phones up, filming everything.

Adam: We’re phone people too, of course.

Jonathan: It is what it is. I’m not really, necessarily saying it’s a bad thing.

…