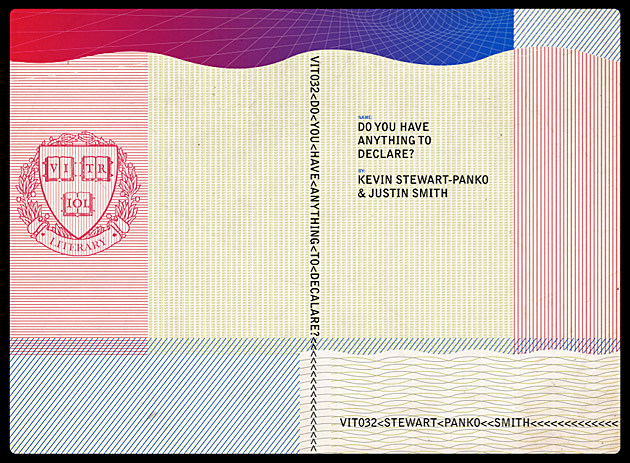

Interview: Kevin Stewart-Panko - Do You Have Anything To Declare?

. . .

For those who are familiar with Kevin Stewart-Panko’s prolific writing career (he regularly writes for Decibel, Terrorizer, Metal Hammer, and Alternative Press, his book, Do You Have Anything To Declare? is anticipated reading. Along with co-author Vitriol Records head and guitarist Justin Smith (Graf Orlock, Ghostlimb, Dangers, Buyer’s Remorse, Death Hymn Number 9), Stewart-Panko decided to investigate one of the most confounding situations that all touring underground metal bands have experienced:

Why is it so hard to cross the goddamn border?

Stewart-Panko and Smith interviewed 75 touring musicians, including Tomas Lindberg (Lock Up, At the Gates, Disfear), Burton C. Bell (Fear Factory), Eugene Robinson (Oxbow), Ben Weinman (Dillinger Escape Plan) and Gazelle Amber Valentine (Jucifer), who provide both humorous and frustrating tales (and some incredibly useful advice) from their experiences crossing the Canadian, American and European borders.

I (unwisely) chose a downtown Baltimore parking lot during the 2013 Maryland Deathfest to chat with Stewart-Panko about touring life and the secret in creating an extremely entertaining and practical book.

. . .

What was it like writing a book with Smith while he lived in another country?

I came up with the project when I was on tour with Cephalic Carnage. About a week after I finished that tour I was in Toronto (Canada) and met up with Justin, and we talked about it and he said, “If you write it, I’ll put it out,” and that was the tipping point. I knew about how to self-release music, so that was a catalyst to get going on this project. My task was to write the majority of the book, and Justin took care of the publishing and distribution end. His band’s (Graf Orlock) drummer, Adam Hunt, designed the cover.

I sent him all these interviews and suggested how to do the intros and the quotes, and he was like, ‘cool.’ He did a few interviews and contributed with some of the introductions, and we just went back and forth, as Justin is in Los Angeles and I’m in Southern Ontario. You see a bit of that in the introductions, but not much in the content. I worked on shaping the book in terms of making sure that the voices flowed so there wasn’t this obvious separation of who wrote what.

Did your background as a touring musician make it easier to talk and understand the experiences that musicians go through in the touring process?

I’ve been writing for much longer than I’ve been playing music, so it was more of a standard interview process. Sometimes if I was doing an interview for a particular magazine and we were getting along, I would ask, “Hey, I’m writing this book. Do you have anything you’d like to contribute?” There were a lot of times where the subject matter wasn’t planned before and others where the interviews were specific to the book. I sent out an email to a bunch of PR people, they would speak to the bands, and the bands had the opportunity to participate or not. It was basically the same process as what I usually do when I write for magazines.

Some of the tales are extremely frustrating. Was it cathartic for musicians to talk about their experiences?

What I did find was that even in cases where it was a really shitty experience for them, they were able to recount and then laugh about it, so in some ways, I think it was cathartic for them. It’s like that Minor Threat song − “Look Back and Laugh.” It’s one of those things where if you hang out with a lot of people in touring bands, it’s a topic that always comes up. So to have to be able to tell that story, to unload it, yeah, but if you are talking to somebody who is organizing these stories to put them together for a book, it was interesting. A couple of people were like, “Wow. I can’t believe no one has ever done this before,” and they were really happy about it.

Some people were cool with naming names – they really didn’t care. There’s a picture in the book of a guy who is showing off his present Visa that was obtained under false pretenses. He didn’t mind, but other people were like, “I’ll tell you this story but I don’t want to divulge too many specific elements.”

One of the surprising things I found in the book was how expensive it could be to obtain visas, and how disheartening it was for bands travelling in Europe, who were essentially blackmailed into paying additional money for their visas. The process seems so subjective as to how much it costs to get into certain countries. Was there anyone who felt that the hassle of touring was enough to make them stop touring?

One of the things that I didn’t know before writing this book, but that came into light in the section where Justin and I were interviewing each other, was how expensive it is to go over there, in terms of flights and if you are bringing instruments – the weight, that kind off stuff. Especially in a lot of Scandinavian countries where they have government–run programs to support musicians, and they have guarantees in which touring musicians are paid with government money.

Justin tells this story in the book where they went over to play in Denmark, played for 10 minutes and got their guaranteed 500 Euro guarantee. If you do touring right and don’t indulge and watch where your money is going, everyone can tour and at least come close to breaking even. It doesn’t have to be super-expensive, but you just have to watch what you do. If you are looking to get into this for riches, it’s not the place to be, but I think a lot of musicians realize that. The ones who didn’t aren’t doing it anymore, but none of the people I spoke to were going to stop touring because of it.

A lot of the stories seemed to include the worry that when bands get to the border, their drug usage is going to be scrutinized by the guards – or the dogs. As one who is a lifelong straight edger, and being on tour with bands like Cephalic Carnage who are pretty public with their weed usage, what is it like for you being surrounded by musicians who spend a substantial amount of time off their tits?

I don’t care. The bands I tour with are for the most part, older dudes. Cephalic Carnage, Hate Eternal, and Exhumed – these are all bands that have been doing this for a while. So even though they like to party, everyone knows what their job is. You can be as irresponsible as you want, but deep down everyone knows what he or she has to do. For me, you take that aspect coupled with the fact that I’m the kind of person who doesn’t really care what you have to do with yourself. Maybe I’m the kind of libertarian – I think that everything should be legal, as long as you take responsibility for everything you do. Just because heroin is there, doesn’t mean that you have to do it. As long as you know and do your job, and know when to fall in line when you have to. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t problems, and that’s also part of the job, because if there weren’t problems they wouldn’t need me there.

Again, a lot of the guys I’ve been out with are veterans. So when they fuck up, they know that they’ve fucked up. It’s then a case of apologizing, and we just move on from there. It’s happened a couple of times but some people get mad about it but then they just let it go. But if might be different for me, because once I get off a tour, I don’t have anything to do with their everyday lives, but they are the ones who have to reconvene and work with each other and rehearse. Maybe there is an undercurrent that is present within their relationships, but for me, it just happens, it’s done, and you move on.

Did any of the interviewees express the desire to let their fans know what they went through in order to travel to their cities / countries? As a Canadian, I was thinking about all the times I complained when a band I liked seemed to avoid playing in my city. After reading this, there is definitely more understanding.

That’s a good point. A lot of people just hear, “Oh, the band didn’t get across the border,” and they tend to chalk it up to laziness. Sometimes that is the case, but maybe the audience needs to understand that there is a lot more that goes into just hauling your stuff into a truck and showing up to play a show. One of the things that surprised me, even though I’ve been involved in the scene since I was 14, was how people didn’t realize things that were very obvious to me. Canada has one of the toughest borders to cross in the world. This could be a good resource for fans too, even if they do not have any travel aspirations or want to be in a band themselves, just to know that this is the kind of shit that is out there.

One of the things is that – and I learned this firsthand when I was with Exhumed and I couldn’t get into MY country – is that even if you can have all your paperwork together, everything neatly organized and ready to go, you can run into someone who is having a bad day and that can be the tipping point of whether you get into a country or not.

You have gone on the road as a merch person, as a roadie, and as a tour manager. What do you prefer doing?

Ultimately when you go out with anyone, you end up being a roadie because everyone has to pull his or her weight, no matter what you are doing. On the last tour I was on (Hate Eternal), I didn’t drive for one minute – not because I couldn’t, but because they didn’t need me to. Ultimately what I prefer doing kind of depends on the band. A lot of the bands in North America are pretty together – they have been together for a while and don’t really need a tour manager. They might need someone to wake them up from a hangover and to get them from place A to place B on time, or to hold on to the money and not spend it on beer, so while I might not serve as an official tour manager, I’m the person who is the most responsible, so in that sense.

I like doing merch because I’m socially awkward. I don’t have a lot of super close friends, but merch allows me to be social in limited amounts and allows me to talk about the stuff that I like to talk about – music, metal and stupid shit. And if that person buys something or not, maybe I’ll see them later on in the day, or the next tour I’m on. I’m really bad at keeping in touch with people and I’m not going to deny that, but that position keeps in contact with that circle of people I meet. MDF is a perfect example of that. The amount of people I’ve met, just by selling them shirts on the road and then meeting them again here, has been weird.

You mention in the book that you reached out to well known, monetary successful bands like Slayer, Metallica and Megadeth and didn’t get a response. What questions would you have asked them that would have been specific to their experiences?

Yeah, fuck those bands. There wouldn’t have been any specific questions. The book was basically about border stories. I got the contacts for their management and contacted them because they have been doing this pre -and post- 9/11, which means prior to all the red tape that artists now have to go through; they toured before the Iron Curtain came down, whatever. Me and Justin come from a DIY background, so we just looked at contacting them as a long shot, so when they didn’t get back to us, we just thought, “Here is our opportunity to call them out and just say, ‘fuck you’!” That’s not going to stop me from going home and listening to Master of Puppets or Reign in Blood, but fuck Dave Mustaine!

Who is your target audience for Do You Have Anything to Declare? If I was in a DIY band or a band that was embarking on a cross-border tour, this book would be essential reading.

I didn’t have a plan – and this is part of my personality, not having a plan! When I decided that it wasn’t going to be an academic book, I figured that it would be an entertaining read for those who are interested in music and just to let people know what is out there. Other bands could read their colleagues’ stories and know what’s going on, and compare. One of the things about this book is that we had to say to ourselves, “Look, we need to have a kill point. We need to know where to stop.” Every band has a story. We could have written this book forever. We only spoke to 75 bands – imagine if we interviewed every band that was playing this weekend (MDF). There is at least one band isn’t playing here because of visa issues (Carpathian Forest).

There is a section in the book that talks about crossing borders legitimately. How to get your visa, both to tour in Canada and the U.S., and how they differ from obtaining a visa in Europe. That could be a resource to anyone who is potentially looking at crossing borders as a band. It used to be a lot easier before 9/11. I toured for 5 years – our last tour as a band happened a few months before 9/11 and not once did we have a piece of paper that said we were legally allowed to tour and make an income in the States! I know of bands that continued to do it after that time – I’m not going to give names, but if you want to do it legit, this book is a starting point. Ultimately I just wanted to have cool stories. I just wanted to have fun putting together this book, and I felt that putting together a bunch of stories was the best way to do it.

. . .

Do You Have Anything to Declare? is available for purchase via Deathwish.