Interview: Averse Sefira

|

Interview by Cosmo Lee |

Averse Sefira are perhaps America’s most potent practitioners of black metal. Their name roughly means “opposing angel”; it comes from the concept of the sephirot in the Kabbalah. This Austin, TX trio, composed of bassist Wrath Sathariel Diabolus, vocalist/guitarist Sanguine Mapsama, and drummer The Carcass, began in 1996. Over time, they’ve built a strong international following, particularly in Brazil; their website has a separate Portuguese section. Advent Parallax (Candlelight, 2008, produced by Tore Stjerna, artwork by Jos A. Smith) is one of this year’s most sonically distinctive records. It’s taut yet expansive, clean yet electric. The band is currently on tour with Gorgoroth – the Gaahl incarnation – in the UK. Wrath writes some of the best tour blogs around; you can see them here.

Earlier this year, I chatted with Wrath while Averse Sefira was on tour with Immolation, Belphegor, and Rotting Christ. Fighting the requisite touring illness, he nonetheless spoke at length about South American fans, numerology, one-man bands, and more.

The band has a strong South American following. How did this come about?

The popularity of the band in South America just kind of happened. Even when we were a demo band, a lot of people from Brazil, in particular, wrote us and supported us and made a big deal out of the band. We kept making friends and making contacts down there. Then we ended up on a Brazilian label for our third album, and we reissued the first album on the same label. Right about that time, we started getting invitations to go play [there]. It culminated in us going down there with Dark Funeral. That was amazing. We haven’t experienced anything like that before or since. The scale of it was just massive. We played to 2000+ people a night, just us and Dark Funeral co-headlining.

Was that the tour they recorded for their live album [De Profundis Clamavi Ad Te Domine]?

Yeah, yeah. That front cover – that was the same crowd that we played to. In fact, right before they started playing, we were backstage behind a barrier, and people were pushing over it to try to get to us. Security finally told us, you either need to go out and talk to them, or you need to get out of sight. We were, like, “OK, we’ll go out and talk to them.” So we went past the barrier, and immediately we were crushed against the wall. My guitarist – he’s a big guy, and he was not standing on the floor. He was just kind of dangling there.

One of the things that also got us an extra-good reputation there is that we gave our fans there a lot of access to us. After every show, we went out to the bar across the street and met everybody. A lot of bands don’t do that; they hide out. That’s what the South Americans want – to be engaged. But they’re also fanatical. They mobbed us. They even tried to steal parts of my hair as souvenirs. Girls were sticking their hands down my pants, kissing me, all sorts of things that would never happen in the States, things that definitely would never happen in Europe.

How does the South American scene compare to the European and American ones?

There’s really nothing like the South American scene because they want you to be larger than life. They want you to be the hero. They want you to take pictures with them and sign autographs and be the rock star. The US is kind of in the middle. There’s a lot of people who are die-hard fans. They get really excited and they want to meet you and talk to you, but they don’t attack you. And then in Europe, it’s against the rules to be like that. Seriously, anything like that is considered bad. And that’s fine. I don’t care if it doesn’t happen. That is not why I do this. I’m not here to sign autographs and be a big shot. But it’s funny the way the Europeans are so preoccupied with avoiding [fandom].

Is it a respect thing or a cultural thing?

No. It’s the fact that they’re so spoiled. I’m serious. They’re spoiled by the amount of bands that they have on that continent, the amount of concerts they have, the amount of fests that they have. And everybody is in a band over there. So it’s almost like they’re not allowed to be any higher up on the food chain than any other band. It’s kind of egalitarian that way. Everybody sort of has to be equal. If you sign an autograph – “Oh, what a poser, what a rock star.”

So that’s the reaction from European fans. How about from bands?

It’s interesting because it’s ultimately bands [with whom] we’ve always tried to cultivate [relationships]. When we started our band, we weren’t really worried about getting fans or supporters. We’ve known all these bands for years. I’ve known Immolation since 1991. We have all these friends in the scene, and we’re more interested in what they think. When we go out and see bands that we like, and play with bands that we like, it’s really validating to us that they respect what we do. The underground helps the band grow bigger, but ultimately we treat this as an art collective where it’s us and all these other bands that we respect, doing what we’re doing regardless of any outside approval.

|

Speaking of such peers, you worked with [producer] Tore Stjerna [from Watain]. Did you record at Necromorbus?

No, we flew him into the States for a month.

Like the previous album [Tetragrammatical Astygmata].

Yeah. He came to Texas; he produced us again. He’s amazing. He’s really great, a fantastic producer, really has an innate understanding of the language of music. I really can’t say more than that. He really helped make the last two albums what they are.

When he’s producing, is he also engineering?

He does everything. He engineers it, he produces it, and he also mixes and masters it. And that’s rare. You don’t find that many people who are able to do all that. He knows exactly what it is he’s going for with the sound. That’s why he does it that way. You know what you’re getting, start to finish.

At one point, the band moved to Rochester, NY, then moved back to Texas. What went on with that?

We were trying to make the band go forward in Texas, and for whatever reason, it just wasn’t working. I mean, it was working – we were producing material. But we couldn’t get a drummer. We’d been using a drum machine for the first demo and the first album. And we just needed a change of scene. For some reason, I decided Rochester was where we had to go. I don’t know why. I liked the New York scene. I liked Canada, too, which was really close. Sanguine didn’t really understand [the decision], but he was behind me on it. So we went and we did find a drummer almost immediately. We played in Toronto with Cradle of Filth – this was in 1999. We played the Milwaukee Metalfest. We played shows all over the Northeast.

Suddenly we were on the map. Everyone kind of

knew we existed. Right around that point, it had been about a year. We just said to each other, “Well, that was cool. Let’s go home.” And we did. Carcass, whom we’d known for years – he’d been in another band – we’d asked him three times to join us, but he wasn’t available – I ran into him at a party right when we got back. I said, “When are you going to stop jerking us around and come drum for us?” And he said, “I’m ready. Let’s do it.”

You referred to Austin as home. What’s its draw for you – especially since you’ve said that the Texas [metal] scene sucks?

It does. Well, I grew up in Texas. Sanguine and I are both from Texas. Carcass was born elsewhere, but he’s mostly been in Texas. When I was growing up, San Antonio, where I lived, was really great. A lot of touring bands came through. I had a band when I was 14, 15. We ended up going to college at the University of Texas. I’d traveled a lot even before I was in this band, and I saw a lot of the country. I didn’t see anything else that looked better to me. I like Texas as a place. I like Texas as an idea because it has a lot of mythology attached to it – the West, the outlaw state, the rebel state. We were a republic once. Serial killers, chainsaw massacres, all that stuff. So there’s a lot about Texas I do like, but the metal scene isn’t one of them. But at this point, it doesn’t matter because we’re plugged into the international scene anyway. We go where we want, and we play with whom we want, and we’re not limited by where we live.

How is the partnership with Candlelight?

Fantastic. We went into this being realistic, saying, “OK, they’re not going to give us the sun and the moon.” No label does that. And they’re not doing that, just to be clear. They’re not treating us any better or any worse than any other band on their roster. But it happens that they treat all their bands pretty well. They come through on all their promises. We get along with them fantastically, which is really good, because sometimes that doesn’t happen. They’ve actually gone further at doing things for us than we thought they would. They’ve met our budgetary requirements. They’ve been pushing the album really, really hard. They seem to be behind us 100%, and I have no reason to believe that will stop anytime soon.

You’ve said you would never sign with a larger label like Century Media or Roadrunner. What do you think of Nachtmystium signing to Century Media?

The reason we wouldn’t sign to Century Media is because we know bands that are on Century Media. And that thing is like a mill. Bands are expected to put out an album every year. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. Tour, album, tour, album, tour, album. There’s no way to really cultivate a bigger artistic idea when you have to do that. I mean, some bands can, but we’re not one of them. If Nachtmystium can do it, that’s great. I don’t know what their contract situation is. Blake [Judd]’s a pretty savvy guy. I don’t know if he’d sign a 10-album contract. A lot of bands did. Get past album three with most bands on that label, even in the old days, and they start getting bad. That’s the reason we wouldn’t do that. Plus, we don’t like the idea of being a small fish in a really, really big pond. At Century Media, I don’t see us growing at all. We’d just be a little satellite, like some kind of Eastern bloc country controlled by Russia. That doesn’t interest us.

Averse Sefira has very skewed tonalities. Where do they come from?

That’s all just Sanguine’s head. He comes from a school of playing not unlike Bob Vigna from Immolation or Piggy from Voivod. He’s influenced by those guys. Also, he’s not a conventional thinker at all. He doesn’t think in linear fashions. Proof of that is sometimes we’re trying to come up with a design scheme for a shirt or artwork for anything that we’re doing – he picks the most faraway method of trying to get to the most obvious conclusion. He does that with his music, too. That’s not a bad thing. It gives us our own sound. It makes our sound pretty unique. That’s where Carcass and I come in. We help temper that, keep it tethered to the earth. [But] we don’t make it real accessible or simple, obviously.

|

How did you link up with Jos A. Smith? Did you give him guidance as to the artwork?

No, that art that he did for us – that was an original piece that he’d done back in 1977. I discovered it in an old art magazine from 1983. When I saw it in there, I was like, “This is it. We have to use this.” It perfectly captured the idea of the [band’s] name. We’ve had a concept for a while of the traveler, the extra-celestial consciousness. And that right there was the embodiment. That was like our main character standing before us.

I didn’t know if [Smith] was still alive. He’s 73 years old. I found him at the Pratt Institute in New York City. I called him up. I was scared out of my mind. I said, “I found this piece, and I would really like to use it.” I just said that we were a band, but I didn’t say what we were. He got very excited and immediately asked, like, 100 questions about it. Before I knew it, he was describing to me how he came up with it.

It turns out that he’s a really powerful mystic. He trained with a Tibetan monk clan to do shamanism and transcendental meditation. That’s how he does all his work – in trances. He’s been involved in witch covens. He also worked with the CIA back in the Korean War, I think. So he’s had an amazing track record. But predominantly, he’s an artist. He pretty much agreed outright to let us have the piece. He wasn’t even into metal, but he understood what we were doing perfectly.

When I saw that figure, I thought, maybe that’s the Averse Sefira. It looked kind of like an angel.

Yes, that’s the simple version of it. Yeah, you got it.

Are there any specific concepts or themes in this record?

The last album was about the terrestrial becoming celestial – the physical form being torn away, and only the spirit is left. This time, it’s the celestial coming back into the terrestrial. The title of the album art is “Machine for a Journey of Indeterminate Depth.” I love the idea that this figure is like an organic machine. It’s sort of like a dirigible that travels. It’s a vessel for consciousness. We’re all like that, in a way. Our bodies are vessels and our minds are the navigators. So we wrote all about that machine. That’s basically the whole album – the celestial form becoming mired in the terrestrial.

If you look at the art, the body is battered and coming apart in places. It’s seen eons of time and damage and war. But it still lives, because it’s unending. The simple version is that we wrote the album about that endless journey of the vessel. The significance of the title… this is something Sanguine should really be talking about, because he’s the big conceptualist. I contribute, but he’s the main lyric writer. We call it Advent Parallax because “advent” is a day of great importance. “Parallax” – the concept of parallax view is to have an object – you look at it from one side, and then you look at it from another angle, a parallax view. The same object takes on a different characteristic because you’re seeing it in a different way. It’s supposed to be the idea of a new vision or process of rebirth. And it’s all embodied through the machine.

Your past lyrics have a lot of numbers. Are you guys interested in numerology?

Absolutely.

What numbers are special for you?

Prime numbers, for one thing. We actually put a lot of different numerical ciphers in our songs. A lot of our songs are written with numerological significance. Now we’re especially interested in exploring more sigil magick. This album in particular is a

hyper-sigil, which is basically a body of work that is one large signifier. We’re exploring more of that because we kind of realized that we’re practicing sigil magick without knowing it. Our logo – that is an example of sigil magick. [Sigils] can also be physically expressed. We’re on tour with Immolation – that’s a perfect example. Have you ever watched Bob [Vigna] play?

No, this will be my first time.

Watch him play. He does this thing [mimics Vigna’s trademark swinging of guitar]. It’s almost like a ritual. If you were to put one of those little flashlights on [his guitar headstock] and to take a picture of it [i.e., with light painting] – sigils. I told him about this, and he didn’t even realize it. I said, “That’s what you are, you’re a sigil mage.” And he really liked that idea.

So numerology, sigil magick, divination – a lot of stuff like that. We borrow off a lot of systems. To use a real world example – when Bruce Lee invented his style of fighting, he hybridized a lot of different ideas. He was a sigil magician, too, by the way. [Mimics Lee’s trademark hand movements] – sigil magick, right there. Basically, what we’ve done is try to distill a lot of magical systems that are useful, and to plug them into an overview that works for us. It’s kind of like the spokes of a wheel.

The practice of magick isn’t common in the “real” world. Do you see your work as an opposition to “reality” or the normal world?

Absolutely. It’s about transcending. It’s about rejecting.

What are you rejecting?

I’m not going to lie and say that when we come off tour, we just sit around and do black metal all day. We have to work really hard. We all have jobs. We all have regular lives that we can’t stand, more or less. The only thing we want to do is this. And this is reality for a lot of bands. The refuge for that is rejecting all the things which are not necessary. There isn’t a job in this country that requires 40 hours a week. I’m not a blue-collar guy; I’m a professional. And even my job – I only need about 25 hours a week to really do it. But I have to be there for 40. It’s such a waste of life.

Magick and ritual practice is, in part, a way to get past that and create a world within a world. That’s one thing I really learned from Jos Smith. He’s a complete master of that. All the stuff that he draws and makes – those things exist. He’s seen them in another place. I am trying to harness that and cultivate that world within a world.

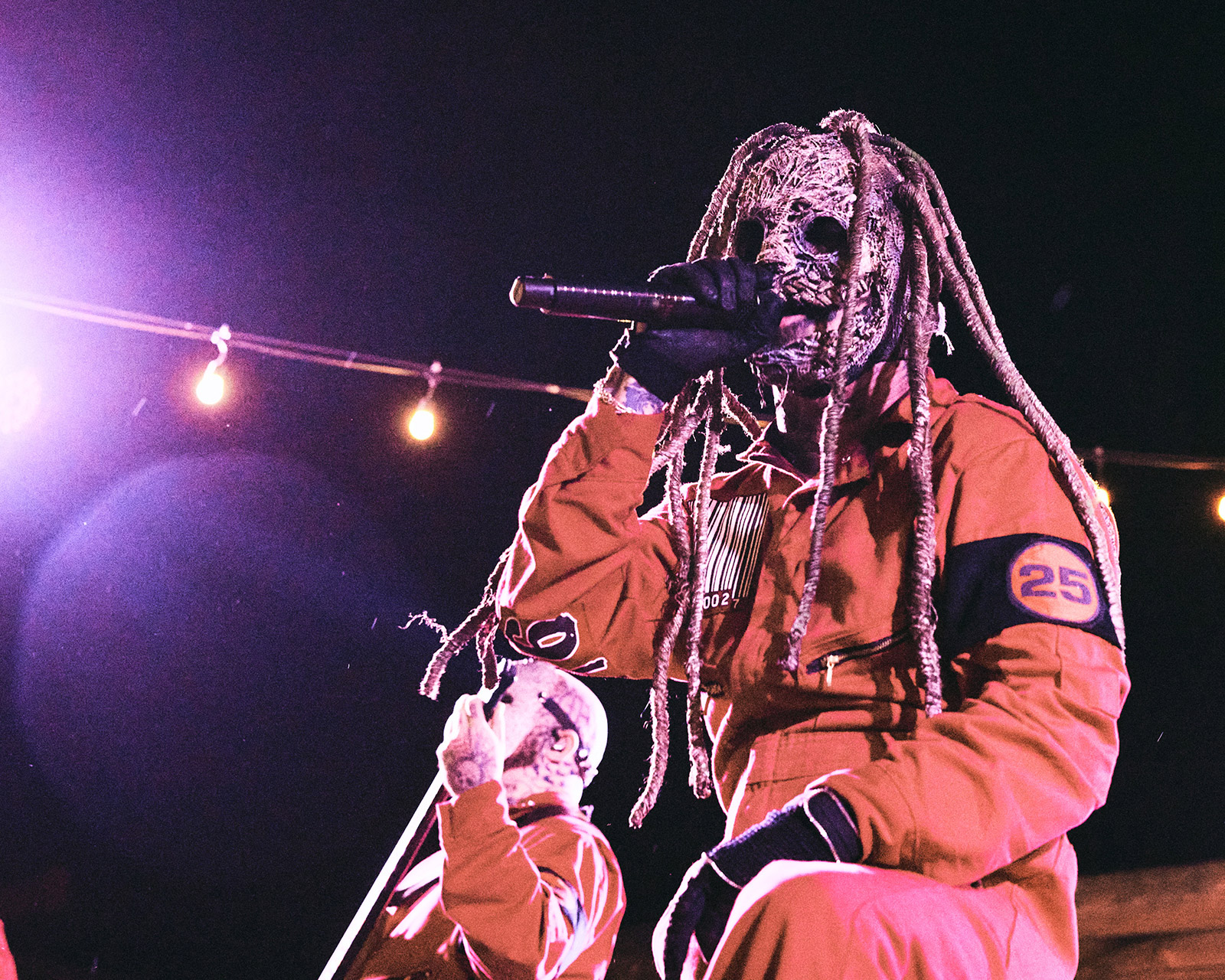

Speaking of signifiers, I was looking at the corpsepaint you guys have. Is there a meaning there?

Oh yeah. The part around the eyes is the crown of thorns. The reason it’s over our eyes is to signify being blinded by the crown of thorns. The lines around our mouths are the threads [from which] we’ve broken free. Our mouths are supposed to be sewn shut to keep us from speaking the truth.

|

The band has been around for over a decade. How have you seen the black metal scene change in that time?

It’s changed a lot in that the overall quality has gone down quite a bit because now everybody thinks they can have a black metal band. There’s a lot of people who get it wrong. They tap into the minimalist aspect – Darkthrone and things like that. People don’t understand that black metal is not meant to be terrible.

[Laughs]

The sound quality, the execution – it’s not supposed to be terrible. Minimalism has its genius. Burzum or Darkthrone – that’s genius, the old stuff. But just playing on shitty instruments on a shitty recording and doing a shitty job of it is not black metal. That is one of the reasons why we’ve never had any reservations about our making music technical, making it more cleanly produced. [But] we’re not trying to make it really shiny. I don’t like the way that a lot of modern metal albums are produced. They’re kind of over-produced. Too many digital effects. It’s very clinical.

But to get back to the question at hand – it’s amazing to watch how many bands we’ve outlasted, big and small. We didn’t plan it that way. It’s just the way it goes. The bands that are meant to last are still here. The overwhelming number of bands that weren’t meant to last aren’t here anymore.

Do you see any new blood coming into the scene?

I hate to say no, but I kind of feel like that’s the case. I think of a band like Watain as new, but they’re only, like, a year and a half younger than we are in terms of when they were formed. They’re kind of the upstart in Europe right now. Everybody’s into Watain right now, which is amazing to me because we played with them before they really broke out. Past our contemporaries that started around the same time we did, I haven’t seen anything that’s really changing the face of the movement or the underground. There are pockets of people who will of course pipe up and go, “Oh, what about ‘Wolfnacht’ from Minnesota?”

[Laughs]

A band pops up with one demo, and it’s like, “Oh, this is it! It’s going to be big!” But that’s the problem. Bands don’t last because people aren’t doing it for the right reasons. People are too quick to want them before they prove that they’re here to stay or create something bigger.

What do you think of the one-man bands, of which the US has a lot – Xasthur, Leviathan, Krohm, things like that?

There’s a lot of people, especially in California, who like Leviathan and Xasthur. Personally, I don’t really get it. I won’t even say it’s bad. I just don’t get it. The biggest problem with one-man bands is that they don’t have any kind of balance. They don’t have any checks and balances or other people in a band editing. If Sanguine was a one-man band, it would probably be really genius on a certain level, but no one would listen to it because it would be so alienating. I’ve listened to stuff like Xasthur and Leviathan. The termination points are really indistinct. It goes on and on and on and on. It’s very cyclical. Some people think that’s great. That’s cool. I don’t have a problem with that.

Here’s an easy way to explain it. They can’t be the vanguard because they are one-man bands. They’re not going out there and breaking their asses and going broke out on the road, and getting out there and trying to spread it. [Instead] they get to sit in their homes and play on their Tascam.

Xasthur now is probably one of the most well-known names in the US scene. And he doesn’t tour – but he’s on Hydra Head, which has major distribution.

Right. My perception of it is that bands like Xasthur – Xasthur in particular. That man is popular with people who aren’t into black metal. That’s what I’ve noticed. You’ve got all these record store folk listening to Xasthur. But they wouldn’t listen to us. They wouldn’t listen to Watain, necessarily. I don’t know if they would even listen to Mayhem or Emperor or any of that stuff. I don’t think you’d ever run into anybody whose two favorite albums are the new Xasthur album and Immortal’s Pure Holocaust. You’re not going to run into that person. It’s usually going to be, like, Xasthur and Death Cab for Cutie. Maybe that’s not right, but you know what I’m saying.

I don’t think [Xasthur]’s reaching the audience that we’re trying to reach: the core audience. He’s got all these fringe people. We would hate to have that audience. They don’t stay with you. They’re not there year after year. They don’t show up wearing the shirt they bought from you in 1998. We experience that all the time. Good luck to him, but he can keep it.

Blog

MySpace

Official Site

Candlelight Records