Dialing In Death: An In-Depth Interview with Hath Drummer/Engineer AJ Viana

In my experience so far across a variety of bands, I’ve found that the single trickiest (and most expensive) aspect of recording is the drums. Specifically, recording live drums in a way that makes that recording sound better than what you’d get with a fully triggered setup. Without the right gear and space—and more importantly, without the proper expertise in your engineer—you might as well be playing on cardboard.

When I learned that Hath‘s drummer AJ Viana was also responsible for engineering and recording their records, I was captivated, and more than just a tad envious as well. A technical wizard on the kit who can also record himself and at industry-leading levels of quality: truly a golden egg to be cherished.

Hath’s 2019 full-length debut Of Rot and Ruin gripped me immediately, especially with regard to Viana’s drumming. In my premiere of their single “Accursed,” I gushed about his potential to be seen as a key figure in death metal drumming. Three years later and he’s taken up the throne in fellow NJ death metal group Cognitive while preparing to drop a massive follow-up album, All That Was Promised, with Hath.

…

…

As Viana’s drumming has progressed, so has his prowess behind the soundboard. Of Rot and Ruin sounded great, but hold it next to All That Was Promised and his maturation as an engineer is clear: the new record just sounds huge. His attention to detail as a producer is on full display as the mix surrounds you, envelops you, but never smothers you.

“Smothering” and “oppressive” are words often used by music writers to talk about metal, myself included, but they’re not fit for Hath. Whereas many death metal bands aim to suffocate—some famously slapping the label right on the tin—Hath surround and enfold.

Find out how Viana gets the results he does with our deep dive below that goes into his approach to recording drums in a studio setting, his evolution as a drummer, how some of the best drum parts are a team effort, and more.

…

…

Let’s start with your musical background. How did you get into drumming, and were the drums your first instrument?

The itch to start drumming was in elementary school. My parents wanted me to join the school band, and ironically enough, the drummers had the least amount of shit to carry, and the least amount of stuff to learn, so I really gravitated towards that.

My parents were very much against it because of the sheer noise that drums make, and wanted me to pick literally anything else, so I chose guitar. But then after a year or two of taking guitar lessons and stuff, but still playing drums in the school band, they caved in and I was able to get my first drum set in the house sometime between 2004 and 2006.

Metal drumming is intensely demanding in terms of not only stamina, but precision and finesse. At which point did you decide to head down this road? What have been some of the trickiest or toughest skills for you to master?

I think it was when I heard the Symbolic record by Death, I had kind of decided that metal drums were going to be what I focused on. I think that and Those Whom the Gods Detest by Nile were two of the most formative records for me when it came to extreme death metal drumming.

And as far as some of the trickiest things to master, I think it’s a little bit of everything, honestly. Some of the staple things are making sure separation on blast beats between hands and feet is dead on, making sure double-bass stuff is even and consistent, but also making sure that overall I’m hitting everything as hard as I can to really give energy behind whatever I’m playing. Those are all things I’m definitely still working on, that’s for sure.

What are some of the more effective practice techniques you’ve used to nail these skills? Any advice for other drummers seeking to burnish their metal chops?

The two Benny Greb DVDs and the two George Kollias DVDs were crucial to me during my practice sessions early on. But honestly, the best advice I can give is learn to record yourself even if it’s with a single mic in a room. Because if you can learn to mix yourself as you’re playing, that’s going to pay off huge live and in the studio. No one likes to hear mostly cymbals, so learning to really smack your drums while keeping them louder than your cymbals is really important.

In all my years of drumming, that’s never once been something I’ve thought about trying, but it makes so much sense as a critical way to refine your technique.

On the topic of refinement—your bandmate Frank [Albanese, guitar and vocals] mentioned that this album began with a potential pool of 23 songs, which was whittled down to the final lineup of nine. How did you all go about making those decisions? What’s to be done with the songs left off this record?

To pare down the songs, we pretty much booked a weekend at the studio where the four of us got together, listened to everything, and basically made a pro and con list for each song. There were some that we cut that we realized sounded too similar to others but not as good, so they were cut. There were others that straight-up sucked, so those were easy to cut. And then there were others where we really liked, but that required a lot of effort to finish, which would then take away focus from the songs we knew were good, so they got cut.

Honestly, we don’t know what’s going to happen with those leftover songs. I know there have been a couple that I’ve started to rework, but it’s really tough to tell until we start writing new songs and see where these old songs fit. More than likely, the songs will get scrapped and the riffs will be used in other tracks if they’re worth it.

What was your writing process like as a group for All That Was Promised? I imagine that with music this technical, you can’t really just hit the jam room and see what comes out.

Yeah, generally speaking, we don’t write songs in a room together. With the tones that we use and just the general nature of being a loud band in a room together, it’s tough to make critical decisions about riffs or how things are played without going through the process of recording the practices or something like that. Which, at that point, we might as well be writing separately.

That being said, we all contribute to the songwriting process in some way, shape, or form. There’s almost never a situation in which the song that gets presented to the group is the song that makes it to the record. There’s always either a structure thing that gets tweaked, or a riff that gets altered, or overdubs and layers and stuff that get added on top. And sometimes those tweaks continue all the way up until the song is finished being recorded.

For All That Was Promised, the bulk of the writing happened right around the start of lockdowns in March 2020. A lot of my sessions at the studio got canceled, so I had an abundance of free time and kind of set a goal for myself to try to write at least a good working skeleton of a song every day. It was during that time that I think we really got a big portion of those songs.

There were a couple of oddball tracks that were written and made it on the record that weren’t a part of that time frame, like there’s a song that was actually written the week we dropped Of Rot and Ruin, and it was pretty much finalized in June of 2019. And there were a couple of songs that Frank wrote here and there that were actually finished closer to when we were getting together to choose the final cut.

…

…

Are you writing and reworking these songs on guitar, or do you write digitally?

Yeah, I do all my writing with a guitar, so depending on what it is I can just copy-paste or cut stuff as needed digitally, or I’ll just totally retrack if it needs it.

How do you approach your drum parts with Hath—and how does that differ, if at all, from your work in The American Standard and Cognitive?

The way that I approach drums is actually surprisingly similar for all of my projects, now that I think about it. It always starts with a very simplistic bare-bones version of a drum beat that I think works with the part but that I can improve on, and that’s even the case with songs that I write.

Usually the things I’m thinking about are, “How can I bring dynamics and some sort of an ebb and flow to the song? How can I make this part more exciting? How can I accent this part more? Am I doing too little or too much?”

And once I get an idea down for all of that, I’ll demo it out with live or programmed drums, and then send it to the band members and then they can be like a second third or fourth pair of ears on it to maybe hear things that I don’t hear or make suggestions that I wouldn’t have thought of.

Can you point to any bits on All That Was Promised that highlight this approach? Are there any spots in particular where your bandmates really helped elevate the drum composition?

Frank definitely helped push me in the tracks “Lithopaedic” and in “Name Them Yet Build No Monument.” Specifically with “Lithopaedic,” he wanted me to do more within the grooves and fills to really help push the song along. Otherwise it felt very same-y with all the drum parts.

In “Name Them,” there was a bit in the center of the track with a sorta droney guitar part, and I couldn’t for the life of me figure out a groove that felt good for the whole section. Frank was kinda like, “Then dont groove over the whole thing,” and so I really experimented a lot of over-the-top drum parts, at least for me, since there aren’t any vocals.

…

…

How did you get into music production? At which point in your journey as a musician did you begin exploring this path?

I feel like I’ve always been the guy in the bands that I’m in that’s been almost too focused on how things were going to sound. I always had an idea for how things should fit together and what kind of tones should be used or how things should be tuned.

Around 2010 to 2012, one of my bands needed to record a demo or an EP or something, and none of the previous producers and studios we used were in business anymore. I had a friend who was actually getting out of recording and had a lot of stuff that he was selling for really cheap, so I bought everything he had and just started down that path. In the beginning, everything sounded like dog shit, but it definitely got me excited to continue and try to get better.

There’s been a massive shift in Hath’s production from Of Rot and Ruin over the past handful of years to the new record. What’s been going on behind the scenes in terms of your evolution as a producer and engineer?

I just think I’ve had more time and more opportunities to work with different bands and try different things sonically to achieve different results. I like to think that I’m a better engineer than I was in 2018 and 2019 just because I’m learning new things every day, and I’m always trying and experimenting with different sounds and different techniques. Even when I’m not recording bands or anything, I’m usually fucking around with guitar tones or setting up microphones on my drum set and taking samples and trying different placements and things.

But I think with Hath, and especially with this record in particular, I wanted to go with something a lot more dynamic and aggressive. I spent a lot of time on the drums to make sure they were the best they could be, both in performance and tone, so I didn’t have to do as much, if any, editing.

And once that foundation was down, that same mentality trickled to the other elements. As long as things were well in-tune, and everything vibed and was tight with each other, then we rolled with the take as it was cut.

…

…

How do you approach the drums from a recording point of view? What’s your recording setup like?

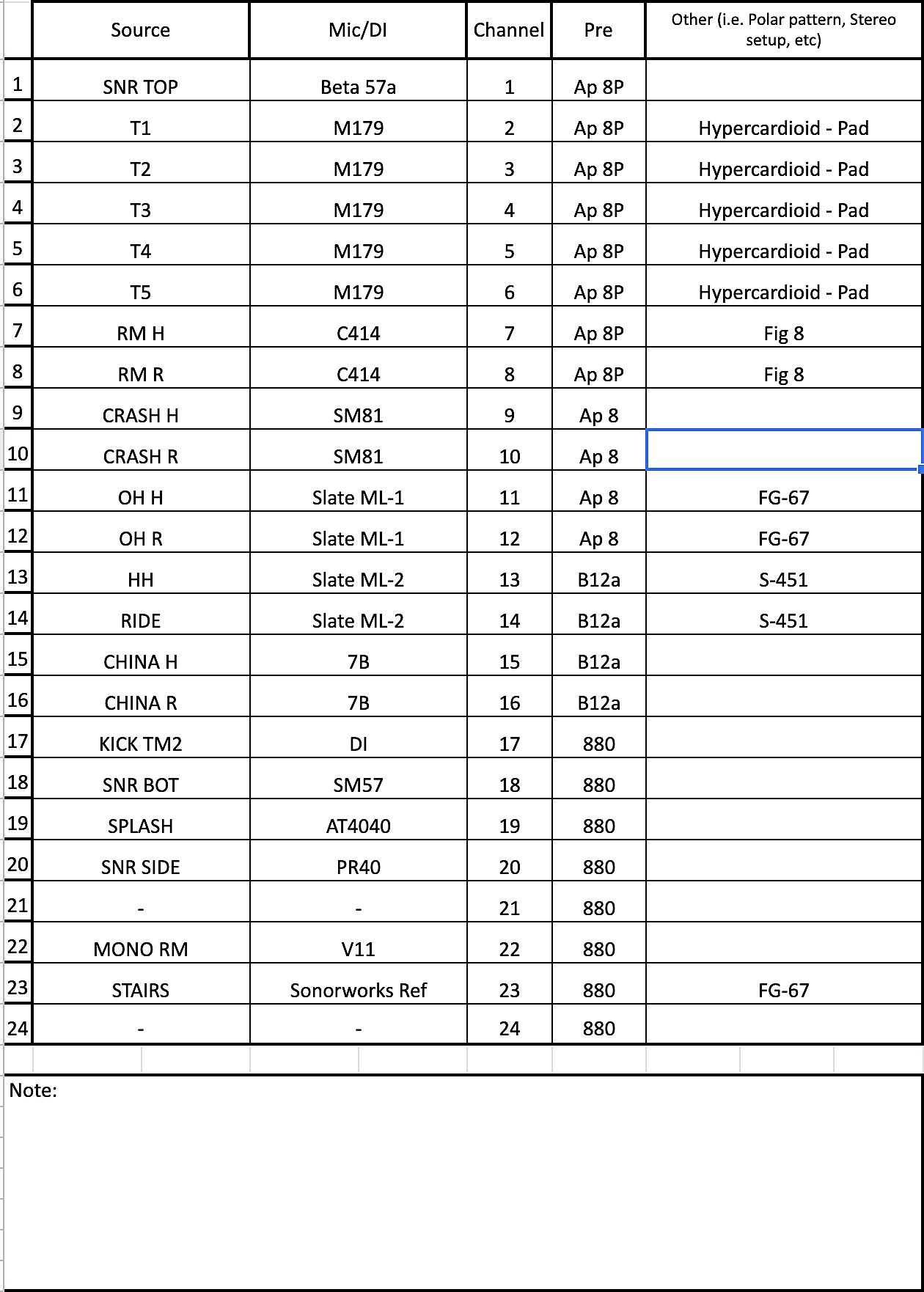

My approach to tracking drums is to try and get the best sound possible straight off the mic. That applies to the overall sound of the drums as well as the performance itself. I have 24 inputs in my live room, so I’m able to get decently involved with the micing setup if needed, and I’ve collected a pretty versatile array of drums and cymbals to be able to put together a balanced-sounding kit.

…

…

Anything other than that, I have a pretty broad selection of drum samples that I’ve made or own to help fill out what’s missing. Like for this record, I used a lot of different room mics to help with adding more excitement to the rooms, and some samples blended into the snare and toms to help get a little bit of extra low end on the toms and some more midrange and snap for the snare.

Generally, my philosophy with tracking drums is to get the direct mics tight and anything else pretty roomy. I like a lot of rooms in my drum sound, so after I get the close stuff sorted, it’s a game of trying to get as much of the drums in the room as I can.

…

…

With my kick technique, I track with the trigger off my pedals for the bass drum so I can then grab MIDI from it and manipulate it for dynamics, and also to pick samples after the fact. One thing I did do a bunch on this record is overdub bass drum too with a mic’d up kick in the room. I did that mostly for some of the softer parts or things where I needed more feel from the kick.

…

…

Speaking of gear, what are you currently playing? Walk me through your kit setup for Hath.

Typically, my “Death Metal” setup is a six-piece kit with three rack toms, a floor tom, kick, and snare. Cymbals would be two crashes, two chinas, 2 effects cymbals like a splash and a stack, a ride, and two hi-hats. New for this record, I wanted to add a second floor tom to help with big tom hits, so I added an 18″ floor tom off to my left side.

…

…

Here’s a list of the drums I used on the record:

Drums:

8 x 7 Tama Rockstar

10 x 8 Tama Starclassic Birch Bubinga

12 x 9 Tama Starclassic B/B

16 x 14 Tama Starclassic B/B

18 x 16 Tama Rockstar

20 x 14 Yamaha Stage Custom Kick

14 x 6.5 Gretsch USA Custom Bell Brass Snare

Cymbals:

18″ Meinl Dark China

14″ Meinl Medium Hats

20″ Meinl Classics Custom Dark Crash

10″ Meinl Classics Custom Dark Splash

10″ Meinl Filter X China / 12” Meinl Classics Custom Dark Trash Splash

20″ Meinl Byzance Brilliant Medium Crash

13″ Sabian HHX Stage Hats

20″ Meinl MB20 Rock China

22″ Meinl MB20 Heavy Bell Ride

When playing with your other bands, do you carry over the same kit arrangement, or do you change things up? How have your drum preferences changed over time?

My kit setup stays the same among my metal bands, for sure. For things like The American Standard, I play a four-piece with a much smaller cymbal setup. Usually hi-hat, ride, and two crashes. Sometimes a china if I’m feeling spicy.

…

…

What factors contributed to your arrival at this kit setup? Whether it’s the sizes and arrangement of the drums, or why the sound of a specific cymbal stood out to you—what let you towards this particular arrangement of gear?

Cymbal-wise, I look for a set that sounds balanced, so everything can be heard, and any one thing isn’t super-loud compared to another. Cymbals also can’t sound super harsh or obnoxious.

Drum-wise, my Birch Bubinga kit has a great balance of low end and smack so that’s always my go to in the studio for me. The two Rockstar drums are only because I don’t have alternatives at the studio.

I chose to add the 18” to the setup this time because I do a lot of big tom accents on this record, and having a tom on the left and right for those parts really helps with filling up the sound space with the impact from those hits.

You’re hitting the road soon for a double-header tour with Hath and Cognitive. What are your strategies for maintaining your stamina and energy levels across two punishing back-to-back sets?

Before the tour I’ll probably practice by myself for a month of just playing both sets back-to-back maybe two or three times a day. The key for me is to get that momentum going and don’t stop. Constant repetition and giving myself no breaks for the extent of the runthrough really help with showtime endurance.

How does this differ from your typical practice routine? Do you have one?

As much as I would love a consistent practice schedule, I just never really have time. I usually have to block out time for myself to practice and usually the month before whatever I have going on. For instance, the band would practice together once a week leading up to the recording dates, but I blocked off an entire month where I just went to the studio once a day for like three to four and worked on the songs.

Who are some contemporary drummers you feel are greatly underrated? What makes them special?

I actually just finished recording Matt Tillet from Wormhole, and it was honestly wild watching him play. Dude is a force for sure. Really creative drumming while playing crazy technical music.

Sam Stewart from Burial in the Sky is another one too. He’s got great technique, and with all the tempo changes and things going on with their music, he’s really good about keeping it all very smooth.

…

All That Was Promised releases on March 4th on Willowtip Records. Learn more about AJ Viana’s studio work at AJ Viana Productions, and catch Hath on their upcoming US tour with Cognitive, Replicant, and Inoculation.

…

…