On "Destin Messianique," Givre Portray the Harsh Realities of Faith (Early Album Stream + Interview)

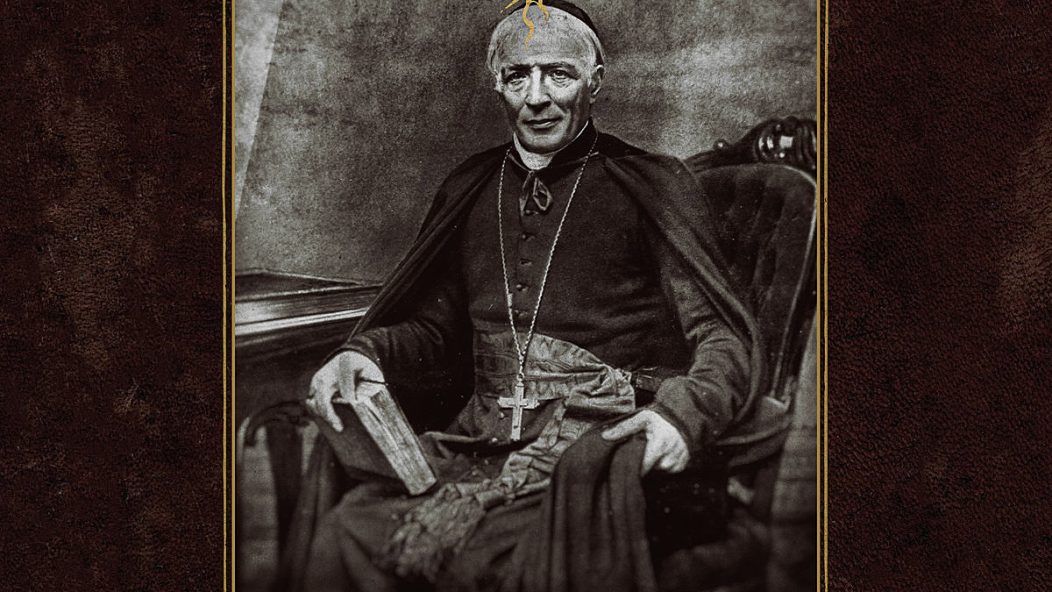

When I last covered Quebecois black metal band Givre my references to religious music must not have been enough of a hint that the band’s themes are largely religious, but not in the usual devotional-or-blasphemous sort of way. Taking the historian’s and orator’s approach, Givre’s new album Destin Messianique tells the story of Catholicism in rural Quebec, one fraught with tales, songs, and poems of extreme devotion through pain and an ascetic lifestyle. Givre’s music, as a result, is similarly miserable, but without the glimmer of hope devotional music generally carries, which makes sense as Givre, themselves, are merely storytellers instead of worshippers.

Now using a much darker sound completely unlike the worship and art music which fueled Le Pressoir mystique, Destin Messianique‘s more aggressive and traditionally melodic music portrays Catholicism for the beast it was in their home province. Recounting extreme, poverty-stricken faith through working the soil, among many other stories, Destin Messianique portrays religion as something sinister, a chokehold on society, simply by showing it for what it is. Listen to Destin Messianique in full and read an interview with Givre below.

…

…

I understand this album involves your region’s interaction with religion. What does religion, specifically Catholicism, mean to you and what made you want to make an album about local Catholic history?

David Caron-Proulx: We’ve all been raised in Catholic school without really understanding the religion. So the project is reflecting historic research on the subject. We approach the subject with a critical mind but with an intention to show that there is still richness and poetry in the texts that we chose as lyrics.

Do you feel there is a beauty in that type of religion? Or are you trying to represent it in a different way?

D C-P: I think it is obvious that Christian art is aimed towards beauty, that is why so many people are visiting churches and cathedrals without even being religious. But our effort with this album is to try to show how people here thought in Quebec in the early 1900’s. The religion was then omnipresent and really pushed people to live simple lives, focusing on land, family and faith.

Givre’s lyrics are only direct citations. We think that the selection of texts makes a sufficient picture of what we want to represent. That is mostly : profound indoctrination of the nation and real poetry finding its way through these dark times.

For example, in “Le laboureur”, we sample an old song that really images the theme of the album :

“Bent on heavy sleeves

Under the eye of God we shall grow old

Away from the noisy big cities

our heart will be proud and quiet

and when our eyes are closed

we’ll hear the wheat sing”

But the band is not aimed to show “beauty in religion.” For eample, in the next album (which is mostly done), we focus mainly on the lives demented woman saints…

What goes into finding these texts which highlight asceticism and devotion?

D C-P: Mostly a fascination for the history of ideas. Jean-Lou is a professional historian, he spends hours searching for old books that look as boring as possible and reads them all.

Jean-Lou David: I go through the written heritage in search of things that instantly seems to come from a certain era, with an outdated flavor, and roots in beliefs that have disappeared and are difficult to understand today

How does it feel to communicate these spiritual anachronisms?

D C-P: The goal is not to maintain a nostalgia about this time, it is rather to try to immerse people in it with the least possible a priori, to make them feel if possible the state of mind of an era, its doubts, its contractions and its beauty

But I would say I have an objective to create songs that I think are good and feel great to play, while trying to fit the ideas.

So are the “spiritual anachronisms” well communicated? I don’t know. But the songs sure are fun to play!

How do you maintain this omniscient separation with such devotional subject matter?

D C-P: Simply, we present literary or audio material from another time. Without criticism, praise, or any commentary. I think we all have our ways to deal with the matter, some of us being more spiritual than others.

In telling these stories, have you learned anything new about religion or gained any insight in the practices surrounding it that you might not have known before?

There is a recurring image, a metaphor, of suffering being the tool that God uses to make souls more fertile as the laborers work the soil. I think this type of fractal symbolism is very striking. Here is another (poorly translated) example:

Don’t curse the pain

‘Cause she’s the plow

Who is the diligent Plowman

Uses to smash your souls

The angels will gather

In the cellars of heaven

Prodigious Harvests

Only if the pain plow

Can tear up your poor ground

And irrigate it with light

(J.K. Huysmans)

The more surprising findings are those surrounding self-inflicted pain. There was a time when ascetic people did some atrocious things to themselves, to very extreme degrees. It is the case for a certain Louise du Néant (literaly Louise of the Void), a 17th century French mystic who was known to be extremely pathologic in the way she humiliated and tortured herself. Reading historical facts about such extremity is, in my opinion, way more disturbing than any death metal/Goregrind lyrics you can find.

Is there anything unique about historic Catholicism where you’re from which might not be immediately known to people who live elsewhere?

D C-P: Few people know it but Quebec was, until the turn of the 1960s, something like a theocracy. Withdrawn into a conservative and agriculturist national identity, the provincial elites were obsessed with the idea that Quebec must remain largely Catholic to preserve its identity. In direct contradiction with the industrial and political modernity that is taking hold everywhere in the West, the Quebec of the Great Darkness sees itself as the last bastion of resistance of Roman Catholicism in North America. Moreover, religious men of the time suggest that Quebec is invested with a true mission of evangelization of the continent, a “Messianic Destiny”.

When it comes to composing, are there any hallmarks you want to meet when expressing these ideas? That is to say, are there specific moods you have in mind when taking these writings into account?

D C-P: I think for this album I was going for an epic yet melancholic sound. But it depends, some songs are just styling exercises. Like the fifth song on the album is kind of a joke, really not the kind of song I’m used to writing. But the point was to take this pre-existing religious melody and try to make it fit in the flow of the album, which in the end, I think works fine.

Is there anything you would like to say about Destin Messianique or Givre as a whole?

D C-P: When we started making music in early 2021, we made three albums back to back, the second being Destin Messianique and we are close to finishing mixing the third album. We also started a live version of the band and did a few shows, which led to composing new songs yet to be recorded in a “live” setting. So just know that we have a lot of music coming your way!

…

Destin Messianique releases September 30th on Eisenwald.