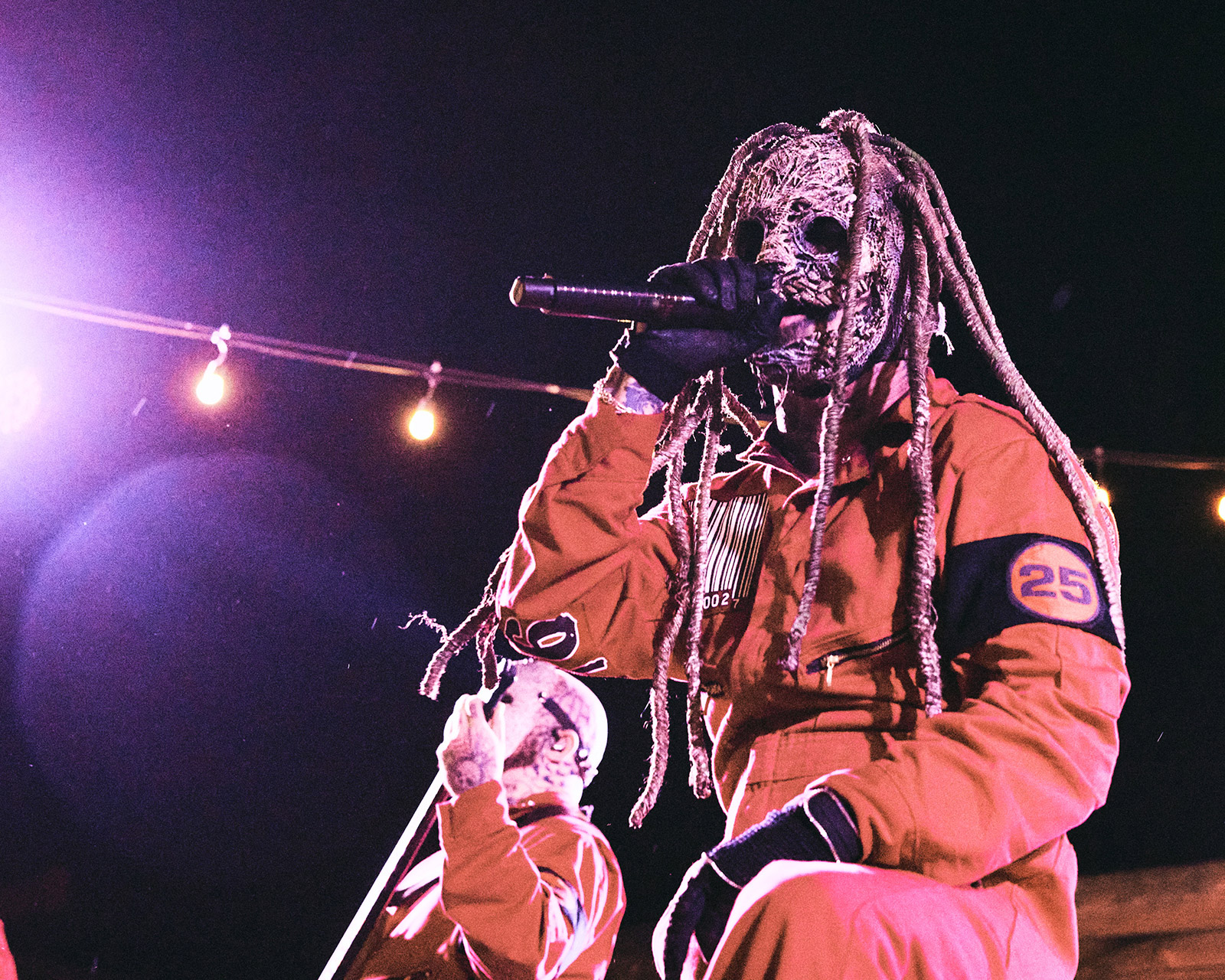

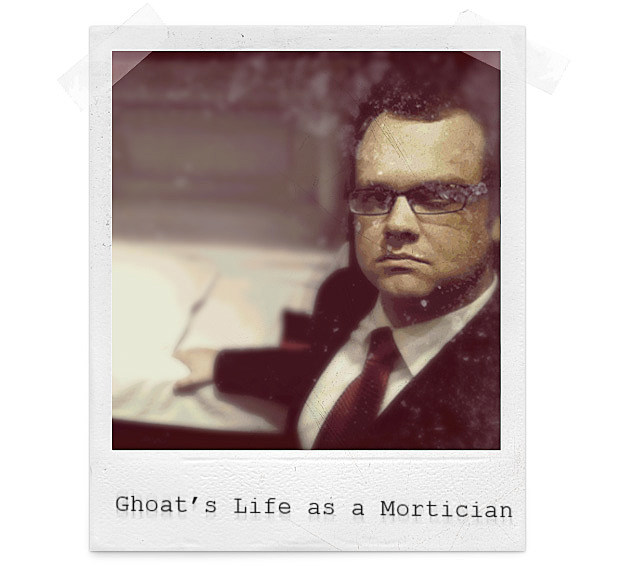

Feature: Ghoat's Life as a Mortician

As humans, we all share a sense of morbid curiosity. It is inescapable. Even if it’s only the urge to look at a car crash, or an inner melancholia fulfilled by watching horror movies, we all have it, and we all satisfy it to a certain degree, in some way, throughout our lives. Death metal musicians certainly have it. We write about it, and display it proudly in our art and on our bodies. But what is death? What is the meaning of it, and how would we really react to it? I am all too familiar with it. I am a mortician.

Yes, a mortician. That’s still a valid term; though funeral director is the preferred nomenclature. It sounds safer and more approachable. Working in the funeral industry (or ‘death-care’ industry) I am surrounded by and confronted with death on a daily basis. My sense of morbid curiosity, and yes I certainly have one, is satiated tenfold. But what I do is far removed from the gore and necrophilia-laden lyrics of our favorite bands.

Balancing my roles at work, in my personal life, and in my musical life is not terribly difficult, but the roles do vary considerably. As a funeral director and embalmer, it is my job to assist families through the most difficult time of their lives. In a nutshell, my number one responsibility is to serve families. This ranges from taking a phone call at all hours (the ‘death-call’ – yep, that’s an industry term) to go to a residence or morgue or hospital room or hospice or medical examiner’s office to pick up a body. Picking up bodies is a job in itself; removals from any kind of facility are relatively easy, but residence calls can be tricky. Picking up a 300 pound woman who died face down on her bathroom floor in the back bedroom of a house with narrow hallways and steep staircases can be an exercise in humility.

You also have the family to consider. Their loved one has just died and you are there to take them away. Most times they are sullen, quiet, detached… they have not yet begun to process what is happening. At other times they are hysterical and unable to handle the situation. This is where my role starts.

We are there to comfort, but not to sugarcoat. We are there to help, but not to make what is happening fake. You cannot put a façade on death. We are taught in mortuary college not to use words or phrases like “passed away” or “moved on” or “expired” (Mama is not milk). You have to use firm language. “Your father died.” Dead. We are not counselors, but we can help assuage their grief momentarily. Our job continues once the body is in our care. We make arrangements for final disposition with the family, prepare the body, and, finally, perform the funeral rite based on the wishes of the family.

My role in all of this is to offer guidance, service, and anything else I can to help families through this difficult time. Now, how does this work for a militant atheist who is generally apathetic to absolutely everything around him? That, too, is an exercise in humility. I am not your typical misanthrope. Yes, I am pretty much disgusted by the society in which we live, but working in the profession I do allows me to put all that aside. I enjoy helping people. I get some kind of twisted fulfillment out of it. Helping someone else in need ultimately makes one feel a whole lot better about one’s own pathetic existence. But not in the same way that giving a bum a cheeseburger will make you feel like you did a good deed. When someone dies, something has to be done. These people are in need and we are there to help. I immensely enjoy my job, regardless of what banality it may entail. Believe me, I stand and stare at my feet through plenty of prayers. All this does not mean that I am some morbid, emotionless drone. I care about the people I help. Again, it goes back to the feeling of contentment which comes from helping someone else. I help because I can, but more-so because I am trained to do so.

That contentment also extends to the preparation of bodies. I am comfortable with death and grief. I handle it well, and I am not scared of a dead body. I would love to know how many death metal dudes’ knees would shake and stomachs heave at the sight and/or the smells of a real dead body. It can definitely get intense. And in the first six months of my work in this field, I saw just about everything I ever thought I would, and since then I have seen everything else. It may be clichéd, but I have seen things I will never unsee. But it does not keep me up at night, and that is where I differ from you. I am not your typical 30-year-old dude, nor am I your typical death metal musician. I wear a suit and tie 99% of the time. I rarely wear a metal t-shirt in public, and I own hundreds of them. I will run into you at Subway and have a normal conversation about the weather, but 10 minutes before that I was standing over a dead body having a conversation with someone else… about the weather. What I do behind closed doors is not the stuff of death metal fantasy, but clinical and sterile. Precise and calculated.

I work with the dead. I take them from their last, worst moment, and make them whole again. After the doctors, after the surgeries, after the car wreck, after the shotgun blast, after disease, after death, you come to me. I put you back together, bathe you, restore you, preserve and present you. I help you on your way to wherever you may go. In death there is calmness, stillness. The pain is gone; the noise of the world is over. The constant struggle to better one’s existence is null. In death we are now all equals. We are all shells of our former selves; we are in that perfect state of perpetuity. No matter how life was lived, or even how you die – of old age, or taken too soon. Whether a calm, peaceful death, or a violent, abrupt death: once we are dead, we are dead. There is not a hierarchy of death. No “my death is better than your death”. In striving for perfection, by definition we will find it upon our demise. It is something we will all have to accept, both for our loved ones and for ourselves.