Dungeon Synth: The East Is Open

Where might dungeon synth find its first major commercial breakout? The question has lingered in the minds of Dungeon Synth's ruminating enthusiasts online. Since its unspoken inception in the 1990s, then later revival on the Internet in the late 2010s, dungeon synth has been an isolated musical-niche with always questionable commercial potential. Historically, odd music of questionable profitability has often found an unexpected dawn of potential in Japan. What commercial potential could dungeon synth reach in Japan then blossom into wider Asia? The idea that a market rests far off in Asia seems contrary to dungeon synth's origins which are deeply intertwined with Scandinavian metal and German electronic music. Those exact roots were already planted in Japan five decades ago. Dungeon synth has both close electronic and ambient musical relatives in Japan. By way of the German musician Klaus Schulze's keyboard experimentation, synthesizer heavy sounds flared across Japan in the 1970s. That direct contact with Schulze's soundscapes inspired the 1980s ambient and new age craze in Japan which, now, could foreshadow dungeon synth's own future in East Asia.

There does exist a Japanese-themed branch of dungeon synth. These “Japonisme” projects are the synth-based structure of dungeon synth crossed with a menagerie of aesthetics derived from Japanese culture/media such as classical Samurai films and mythology. The 2019 Serbian project Shogun's Castle (embracing dungeon synth's literary side) rendered the historical warrior-code of the samurai, Bushido, in a synth-based Ambient style self-described as “Samurai Synth”. The French project Goryō's self-titled debut album samples the movie The 47 Ronin (1941) which introduced a multimedia twist to the album. The Finnish project Ayakashi (アヤカシ) is an exploration of Japanese folklore and atmospheric horror through albums such as 天女の夢 (Tennyonoyume)(2022), 神隠し (Kamikakushi) (2022), and Songs of Moonlight and Rain (2023). Ayakashi invokes Japan's culture on a deeper linguistic level by rendering their album titles in Japanese: 天女の夢 (Tennyonoyume) can be read in English as“Heavenly Woman of Dreams”, then 神隠し (Kamikakushi) can be translated as “Spirited Away”—though the kanji character reading of Kamikakushi suggests a “hiding away” by the gods. Then there are Dungeon Synth-adjacent projects such as the Ukrainian, dark ambient project Gates of Moreheim's Omagatoki (2020) that bills itself as, “A journey into the spiritual world of the Japanese occult, accompanied by traditional music and dark ambiance.”

…

…

The first two albums to test the waters of (partially) Japanese language dungeon synth are Count Shiritsu and Leaking Crypt. Count Shiritsu's Welcome Home seeks to combine dungeon synth's Gothic stylings with the classic Japanese storytelling of a revenge plot. Leaking Crypt is rather minimalist (foregoing Count Shiritsu's baroque plot elements) while embracing softer elements of dungeon synth and mixing them with an eerie chiptune sound. Both Count Shiritsu and Leaking Crypt offer an exterior view to a music genre that, for much of its brief history, has been contained to the Western Internet. All these projects are drawing on a perceived kinship with Japanese ambient music (be it through albums, movies, or games) that does truly exist and can be certified in several ambient forerunners in dungeon synth's musical genealogy.

Dungeon synth has retroactive connections to Japan if one traces a lineage through the genre's godfather: Klaus Schulze. Schulze, a founding member of the German band Tangerine Dream, was influential on Japanese new age and kankyō ongaku (“environmental music”). Schulze would instruct Masanori Takahashi, a member of the prog-rock Far East Family Band, in synthesizers and electronic rock music production. Schulze claims the two met in 1975, but Masanori has multiple times insisted their first contact was three years earlier in 1972. While it is debatable how deep Schulze and Masanori's actual relationship was both remembered the other as an impressive musical talent. The interaction was impactful enough on Masanori's career to inspire his transformation into the transcendental identity of “Kitaro”. Masanori took the nickname “Kitaro” from the Horror comic book series GeGeGe no Kitaro as, supposedly, his hair resembled the main character's: Kitaro's. Schulze's music explored the technological and alien; Kitaro's (or Masanori's) music embodied the natural and metaphysical. The two applied, in their respective languages, Western and Eastern philosophy to a synthesizer-based musical structure. Schulze approached the synthesizer through Science-Fiction and Masanori approached it through spirituality.

…

…

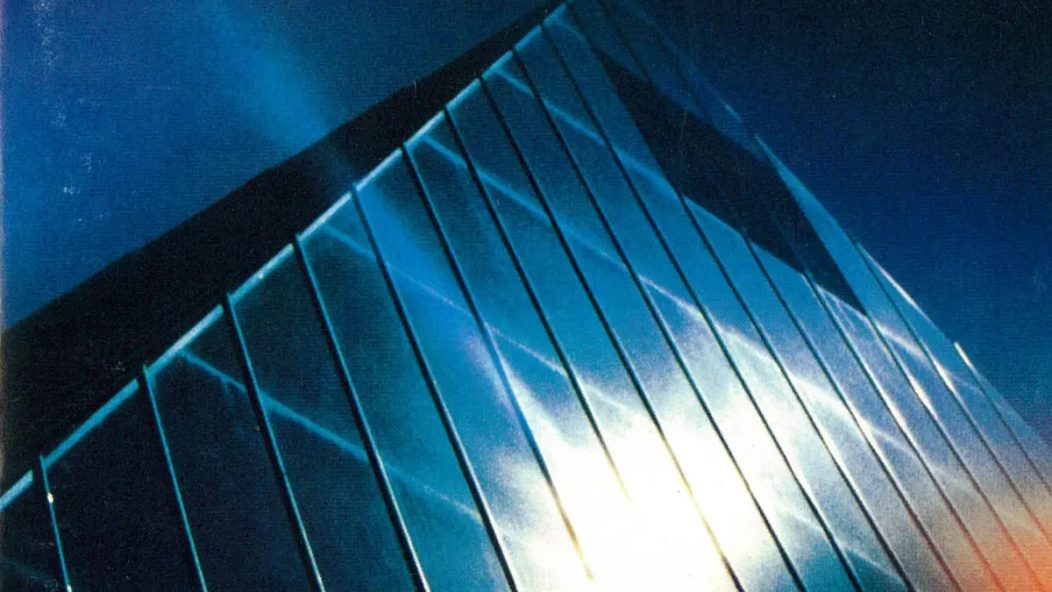

Masanori's first outing as “Kitaro” would establish earnest parallels to Schulze's 1970s work. Kitaro would debut with the album 天界 (Tenkai), known as Astral Voyage in English, in 1978. Kitaro's work fused the flutes of Japanese folk music with the keyboards of ambient, progressive rock. The album made use of instruments as distinct as the sitar to convey the journey from the profane to the sacred in songs such as “By the Seaside”, “Soul of the Sea”, “Micro Cosmos”, “Endless Dreamy World”, and “Astral Voyage”. The identity of Kitaro, as a musician, looked to display the transfiguration of the soul (perhaps in Buddhist ideals) through musical technology. One year earlier, in 1977, Klaus Schulze had produced the thematically similar album: Mirage. Unlike Kitaro's folk inspired spiritualism, Schulze's album was detached space music that removed the human element from the equation. Mirage was a clean album of transformation, but all the human element, and thus error, was removed from it. While only composed of two tracks, “Velvet Voyage” and “Crystal Lake”, Mirage established the same astral, or even spectral, soundscape as Tenkai did. Schulze's astral voyage was as perfect as an alien crystalline structure. Schulze was motivated by a German philosophy of sonic engineering while Kitaro was fed by a Japanese philosophy of sonic refinement, but their unique musical perspectives produced two similar albums. The kinship was audible in this advent of the new age.

…

…

Schulze's contacts in Japan were not confined only to what would become representative of new age music. The German maestro was a key component of Japanese percussionist Stomu Yamashta's international supergroup Go which was active between 1976-1978 (the group featured experimental keyboardist Steve Winwood and guitarist Ai Di Meola). Yamashta, the group's symbolic head, was influenced by many of the typical classical and electronic musical influences that would later inspire dungeon synth: Tchaikovsky, Jean Michael Jarre, and Yamashta's own father conducted the Kyoto Philharmonic Orchestra. After the group's disbandment in 1976, Yamashta would go on to compose the album series Iroha which included the ambient, Schulze-inspired, Sui (Water) in 1982. Sui would become a classic of kankyō ongaku, or environmental music, and a testament to Yamashta's own international influences.

…

…

Schulze's sonic shadow can be heard in the swirl of ambient and avant-garde DNA that Yamashta's “environmental music” composed itself from. Schulze downplayed his influence in Japan, mainly in interviews throughout his later career, but his time there stands as a spiritual link between Western and Eastern new age music. It is no surprise then that post-Schulze “environmental music” shares many key traits with Dungeon Synth.

The 1980s kankyō ongaku movement is—outside the Internet—unknown in English, but it was influenced by both Eastern and Western branches of experimental ambient music. “Environmental music” exists under the same mechanical framework as Western ambient music, but with Japanese social philosophy applied to that framework. Goldenstein Music provides this sketch-work definition of kankyō ongaku: “Kankyō Ongaku”, or 'environmental music', is a Japanese genre of music that was established in the 1980s as a reaction to the rapid urbanisation and economic development of the time. Influenced by Erik Satie and Brian Eno, it consists of minimalist electronica infused with the ambient sounds of nature.” Unlike dungeon synth, kankyō ongaku's popular variants were more receptive towards open commercialism. The origins of the Japanese genre rest in its outright commercial purpose and use in public settings. The iconic albums of “environmental music” were developed for explicit commercial environments: Haroumi Hosono's Watering a Flower (1984) was funded by a Tokyo retail store, Yasuaki Shimizu's Music for Commercials (1987) was produced for TV commercials, and Takashi Kokubo's Get at the Wave (1987) was developed for selling air conditioners. It can be argued that the modern use of the name “kankyō ongaku” is an ad hoc rationalization to establish the image of a unified movement that did not actually exist in the 1980s—the current concept of dungeon synth exists in much the same vein. Both are genres whose origins were defined later by enthusiasts willing to establish a genealogy through research and discussion. In both cases the synthesizer was a key to a spiritual community embodied in a wordless soundscape.

The idea that dungeon synth could have a greater future in Japan does have a historical precedent in the tectonic emergence of the term “new age” in Japan. Schulze's influence on Kitaro has been mentioned, but Kitaro, due to Schulze, was responsible for establishing new age music in Japan. Kitaro's debut album Astral Voyage (1978) (Tenkai in Japan) represented an emergence from Schulze-derived electronic rock to outright new age (or ambient) which would cement the use of the keyboard, flutes, and synthesizer in Japanese new age music. In 1980, Kitaro would score the popular Sino-Japanese documentary series The Silk Road, produced by NHK (Japanese Broadcasting Corporation), which would skyrocket Kitaro to fame in Japan and ignite a boom for new age music across Asia. Despite this, outside expensive imports in the United States and Germany, Kitaro's albums would remain exclusive to Japan until he signed a deal with Geffen Records in 1986. The new age boom in Japan would soon turn Japan into a net-importer for new age and ambient music (as well as nursing its refined local acts such as Kitaro). The small Japanese label Yupiteru Records (active from 1976-1984) made a notable business off importing profit-negative European/American jazz and new age music, then marketing it to Japanese audiences and other Asian markets such as in Korea. Yupiteru's strategy was profitable enough to save one group: Cusco. The German synthesizer-instrumental duo of Michael Holm and Kristian Schultze's early tenure as Cusco was floated, if not made, by Japanese sales after their first album Desert Island (1980) failed to sell in Germany. By 1984, Billboard reported Cusco's “massive sales” were thanks to the Korean and Japanese markets. Like Kitaro, Holm and Schultze's band Cusco predated the term “new age” or “new instrumental music”, but both terms, post-1986, were retroactively applied to market these ambient projects. Both Kitaro and Cusco, due to the influence of German rock, were inspired to experiment with synthesizers and musical philosophy. It is somewhat amusing then that Kitaro outright rejects the term “new age” and instead refers to his music as “...a kind of rock symphony” inspired by Otis Redding and Tangerine Dream. Either way, for or against the label of “new age”, Kitaro's popularity established a native market for ambient music in Japan that made international imports profitable internationally.

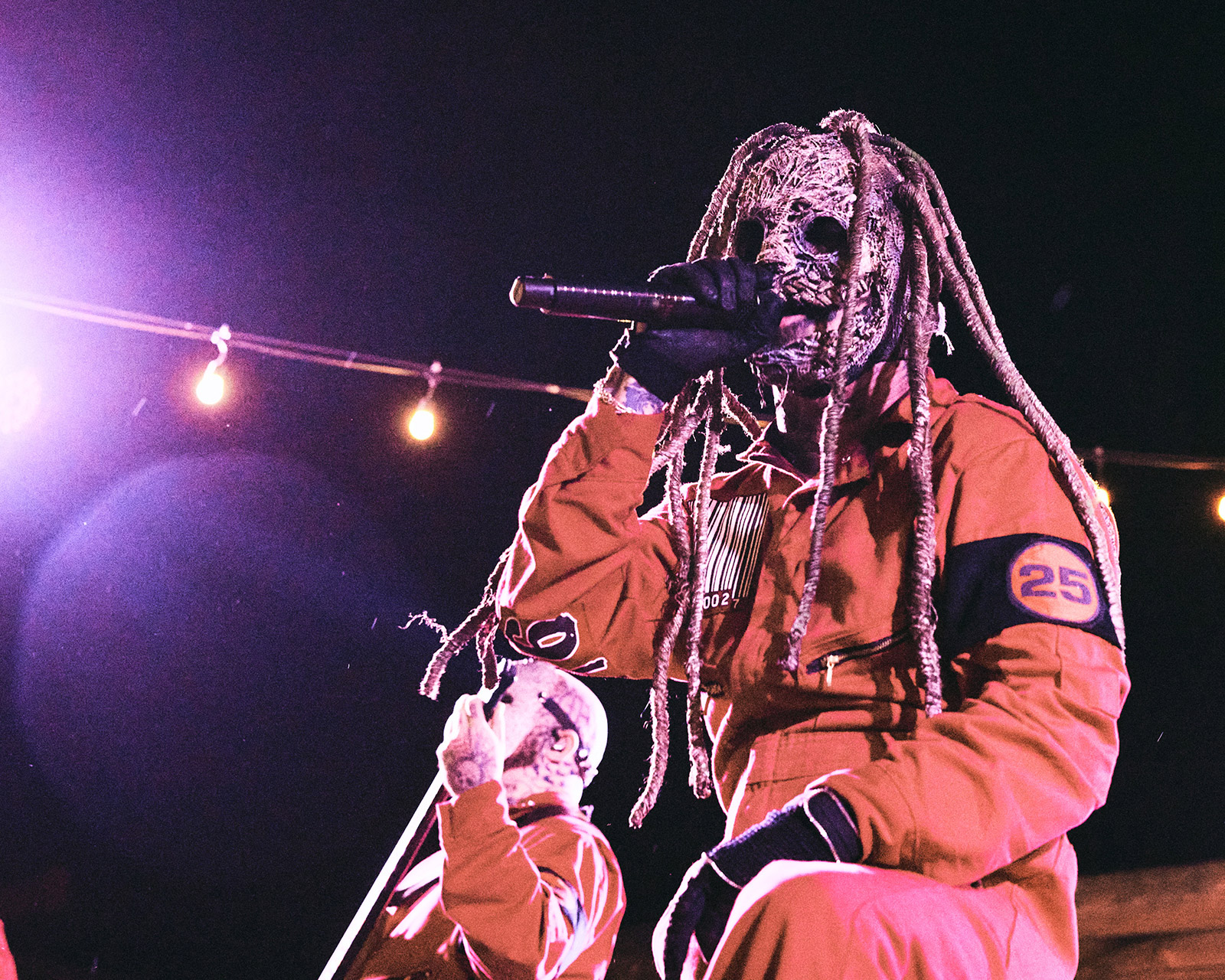

Kitaro's influence on Japanese music has seen the consequential blending of Japanese folk music, ambient, rock, metal, and, in recent times, Internet music along the bleeding edge of those once distinct markets. One example of Kitaro's unspoken, pervasive influence is in the transformation of the Japanese metal band Sigh. Sigh was founded as a Japanese answer to emergent Norwegian black metal, having business links to the 1990s Norwegian black metal scene, and their first album Scorn Defeat (1993) was released by the label Deathlike Silence internationally. Since 1993 though Sigh has drifted towards a sort of experimental folk metal (though not exactly Ambient) embracing more and more: themes of Japanese mythological, instruments such as flutes, and purposefully distorted synth production for their recent albums Heir To Despair (2018) and Shiki (2022). While Sigh could never be called Dungeon Synth, their transformation shows a beneficial mixing of the Schulze-Kitaro ambient and Norwegian black metal niches in the modern Japanese music market.

…

…

That potent mixture, in a somewhat confounding manner, has even breached Japanese popular music with the emergence of Wagakki Band (literally: “Japanese Instrument Band”). Founded in 2013, Wagakki Band's genre is a heavily disputed mixture of J-pop, Japanese folk rock, and metal, but the group's conceptual fame comes from the extravagant use of ancient Japanese instruments and vocal poetry in a modern production style. Part of the band's early popularity was achieved by producing covers of popular, online Vocaloid (a Japanese voice synthesizer program) songs, usually from YouTube or the Japanese equivalent Nico Nico Douga, such as the music video “Tengaku” which now has thirty-one million views. It is hard to claim Wagakki Band as anything truly “metal”, but the group seeks to combine the post-Kitaro Japanese music market with digital music culture in a bombastic style. The legacy of Kitaro's ambient music explosion is still alive and well, though obscured, in Japan.

…

…

Could dungeon synth then draw out and reinvigorate that decades old market that has always existed for ambient music in Japan? It is a question of accessing that market. The first hurdle is the lack of a major engine for the importation of Dungeon Synth into Japan. As in the case of Kitaro preceding Cusco, a robust native interest had to be established first before demand for foreign material cohered—though the Internet has made this instantaneous exchange much more porous. Dungeon synth may already have a ready open niche it can embed itself in across the digital world: video game music. Modern dungeon synth, post-2012, contains a tangible influence from Japanese video games. The kinship between Dungeon Synth and RPG (Role Playing Game) music has long been noted by its performers and producers. Leaking Crypt labels their own music as somewhere between chiptune, dungeon synth, new age, and ambient music. Both Dungeon Synth and chiptune use anachronistic electronic sounds and textures to inspire sonic melancholy of either nostalgia (chiptune) or ennui (dungeon synth). Popular dungeon synth artists, such as Erang, have acknowledged such a fondness for the video game soundtracks. SNES games such as The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Secret of Mana are influential on Erang's expansive oeuvre and musical style. This creates an exponential influence as Erang is one of the most influential artists to emerge from contemporary Dungeon Synth circles thus influencing other artists. Erang has explained the inspiration in a 2012 interview with Andrew Werdna: “My first inspiration to make Erang music really came from the cheap sound of old synth. I love it. It reminds me of old computer or rpg games...” Appropriate then that Erang, alongside other dungeon synth artists, contributed Dungeon Synth music to the popular independent video game The Longing in 2020. Older, established artists, such as Mortiis, have been somewhat dismissive of video game music's influence on Dungeon Synth. Yet, video game soundtracks are undoubtedly a major influence on the post-2012, amorphous category of “modern dungeon synth”.

…

…

These links establish a deep, mutually beneficial relationship between the building blocks of dungeon synth and Japanese music culture. Dungeon synth, an estranged child of metal and new age, could soon follow the path of its predecessors to maturity. Today, cultural barriers between obscure music cultures are no longer as oceanic as they once were. Though, as Klause Schulze and Kitaro proved in the 1970s, were such barriers ever so solid? There could be an undetected market in Japan waiting to blossom into an outlet for Dungeon Synth in the coming decade. The sun needs only to dawn on the crypts of dungeon synth for listeners to plunder the catacombs of material. The question remains about where that place in the sunlight will dawn for dungeon synth. It can only be concluded that the East is open and its soul is electronic.

-- William Pauper