The Past Is Only the Future With the Lights On

…

“Time is out of joint.”

— Hamlet

“My head really hurts.”

— Black Flag

…

Smoke braids itself up from the mountains around Taos and into the darkening sky as we hove close to Raton, a ramshackle sweep of faltering trailers dotted out alongside the highway in northern New Mexico. Bats cut across our high beams.

“We’re driving into Hell,” Will, my traveling companion, says. “Well, first Raton, then Denver, then Warped Tour. So yeah: Hell.”

“Pioneering,” as John Berryman wrote, “is not feeling well.” And I am becoming unwell as we drive. I’ve made a crucial mistake: I had intentions. I thought I knew what I wanted and needed to see ex ante.

I pitched this piece last year, and I’d been thinking about it since Invisible Oranges accepted it. I intended it to be part experiential postcard, part political analysis. I intended to focus on the U.S. highway system, the major piece of infrastructure, now failing along with the rest of our infrastructure, upon which Warped Tour relies. And within this focus I intended to showcase the build-out of the American empire after the Second World War under Eisenhower, under whose aegis the interstate system tethered together our disparate confederation. I intended to point out that you can land planes on the highway, that this is by design, that the highway system is inextricably linked to our “defense” industry, and that there was no way we could have gotten one without the other. I intended to use Eisenhower’s “military industrial complex” speech as a fulcrum to show that the death of American optimism (of which Warped is an expression), the toll of maintaining our global empire, and our empire’s benighted final throes would converge and could therefore be analyzed at Warped. In other words, I saw the Denver date of Warped Tour as an object lesson in what has rotten in America, whatever sick fruit it bore before. This instinct was not totally misguided.

…

…

…

Yet by the time Will and I push through New Mexico’s northernmost reaches the night before the Warped date, the truth asserts itself: my preparations are foundering; I am now adrift. Rather than the rapid coming of America’s demise as it plummets into the maw of nihilistic consumption and imperial over-expansion, what I begin to sense is that what I otherwise and with aplomb spend, waste, kill — namely time — veils and beguiles and relucts my attempts to ground myself in any particular “now,” let alone locate a specific “then,” to say nothing of a possible “next.” This is, in part, because of the nature of the Warped Tour itself.

I never got to go when I was a kid, but I did go to Lollapalooza 2003, back when it was, like Warped, a traveling tour. Warped is the last of its kind and Kevin Lyman, the tour’s founder, announced in 2017 that after 24 years, the tour’s time was up. After 2018, the half-shopping mall, half-teen haven will expire. There’s no surprise here: guitar music doesn’t generate the kind of cash it used to. But when I saw the lineup it was like doing the Time Warp: Harm’s Way, Sharptooth, Issues, Senses Fail, Simple Plan, The Used, Reel Big Fish. This genealogy of bands spans four different presidential administrations and the majority of my time on this Earth. When I was growing up, Warped was just a thing that is, like police brutality or beans in the soup. It was inseparable from the teenage suburban experience as I knew it. Warped was less a tour than part of a context. That this is its last year certainly feels like the end of an era. As with any ending, the ground drops out from under you. It’s a cartoon physics: your legs keep running in midair and then you turn back: the cliff’s edge, you notice, is behind you.

And then there is the terraformed suburban blight of Colorado to contend with: first, there lies Pueblo, which is more a consortium of living situations slapped down around a refinery than anything like coherent municipality; next, there’s Colorado Springs, a composite car dealership and U.S. Air Force base. I begin to dissociate when we enter Denver’s city limits. It’s an endlessness of concrete and strip malls enfenced by mountains themselves made invisible by light pollution’s interplay with night’s obscurity. It looks like home to me, like the quiltwork prairie of Illinois long since patched over with asphalt and cul-de-sacs. We’re driving backward in time: we spend the night at a friend’s childhood home in his childhood bedroom in the basement. The house sits on a corner like my best friend’s mother’s house in a neighborhood just like it back in Illinois. Whatever boundary splits past from present blurs before me. Memories slip through the dilation and enter the present before my eyes. We could be anywhere, I think. This could be any year of my life.

I call my partner to let her know we’ve arrived safely.

“How are you?”

“I’m staring at an open box on the floor.”

“What’s in it?”

“Nothing,” I say. “It’s empty. It looks like a little kid wrote ‘BAD’ on the side of it.”

“Nothing inside it anymore,” she says.

…

What is an American to do with history? The obvious answer: Face it.

But America is a country perpetuated in part by an inherent dishonesty about its past. Thanksgiving cloaks the dark legacy of settler-colonialism and indigenous extermination — still ongoing. Black History Month, its province the shortest month of the year, arrives as a litany of “firsts” trucked with a parade wrong-headedness exposed first by the Civil War and corrected by Martin Luther King, Jr. As if chattel slavery did not, even at the moment the ink dried, lay bare the farce of our founding documents. As if a generations-long “debate” exacerbated by a football game with muskets recounted as a contest to see who was honorable enough to decide what ought to be done with the black population healed this legacy and absolved all of any culpability. And this is to say nothing of the eight-hour workday, an eroding “given” I did not know people fought and died for until I was an adult and far from the clutches of any educational institution. Besides, May Day, President Obama announced, is now Loyalty Day.

Lastly, it’s scarcely pointed out who benefited, who continues to benefit, and how and why. “The strong decide what is right while the weak suffer what they must,” goes an ethos the powerful hope the powerless forget. Though the powerful in America have themselves forgotten — if they ever learned it — that not long after those words left Athenian lips their empire, such as it was, plummeted into plague and cannibalism only to succumb to the depredations of the Spartan oligarchs. It seems the only thing that has truly trickled down in America is amnesia.

I do not aim to play the victim here and imply that my inability to disaggregate past from present falls squarely on the shoulders of our disingenuous national story. Rather, it’s that I realize — at Denver’s Pepsi Center, in whose parking lot the Warped date unfolds, backgrounded by a theme park replete with tilt-a-whirls and rollercoasters and flanked by an industrial train line — that the fact that I cannot synthesize a coherent story of myself, which is to say a story of my past, is itself a distinctly American problem, and that I am, despite myself, well within our grand tradition.

The first thing I hear when we make it past the gates comes from a roadie selling a map and schedule to a teenage boy: “I went to my first Warped Tour before you were born.”

He is not talking down to him. He is trying to communicate what the words can’t carry: disbelief, maybe. And loss. Nothing gold can’t not stay is how America would like it to be. And yet here we are. It’s a startlingly vulnerable encounter, and like all teenage boys, the recipient of this sentence is at a loss for words.

“Yeah,” the boy says, taking his map and schedule and walking away.

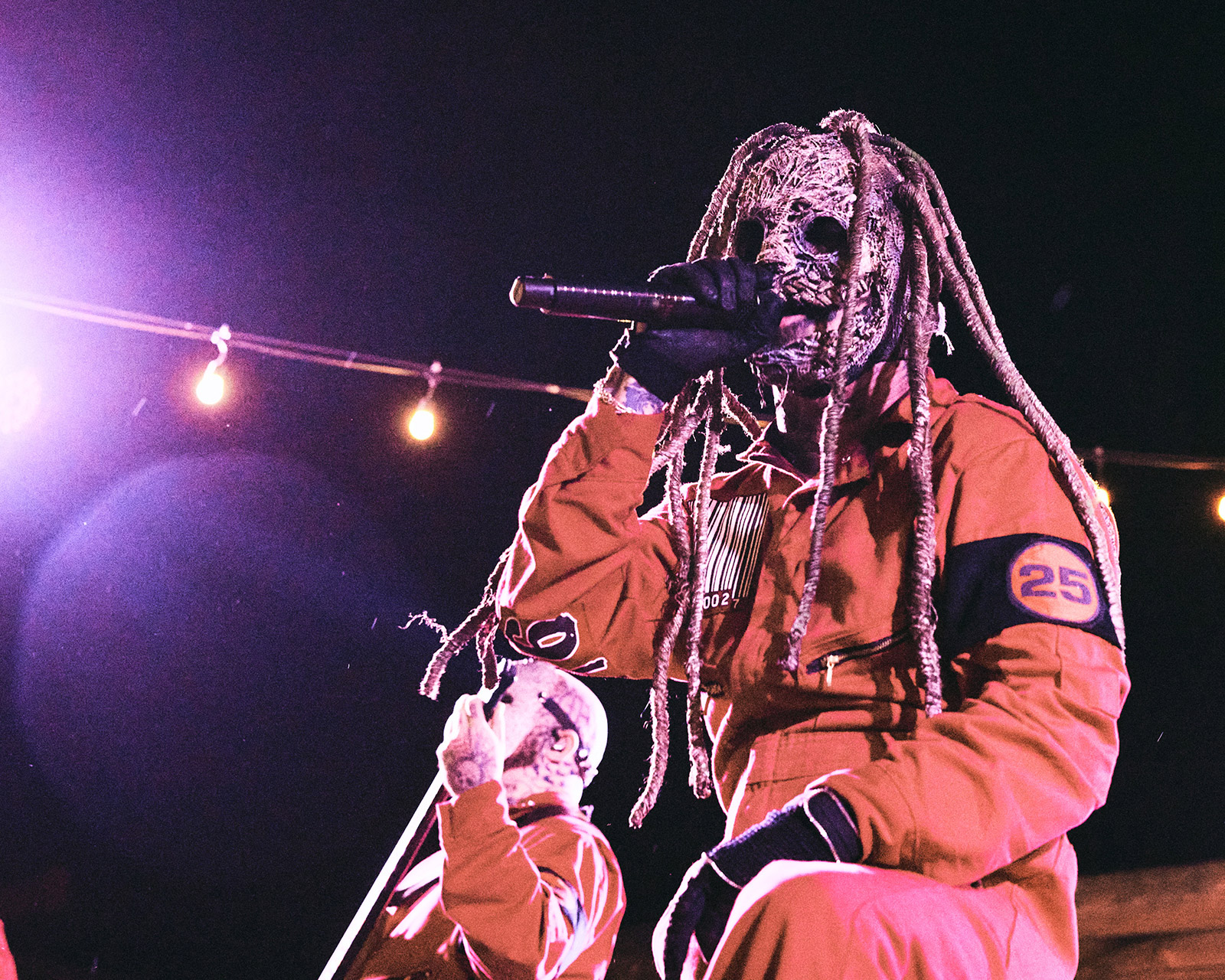

It’s not long after this that Will and I make our way to one of the Monster Energy Drink-sponsored stages. Those stages sit beside one another. Harm’s Way comes on. What I see of the pit is that it’s as violent as I would have wanted when I was a kid: kinetic, damaging, offering up brief glimpses of camaraderie and transcendence. Harm’s Way kills. They do the impossible: their liveset sounds just like the record, yet better for their actual presence.

…

…

James Pligg, their lead singer, is a walking pillar of death. He hops around as he screams and punches the air just below his waist. As I watch, I feel like I’m getting hit in the chest with a sledgehammer. Between songs, the guitarist says a few words. Otherwise: nothing. They didn’t come here to play to us, but play through us. It’s a type of aggression that does not repeat itself for the rest of the day. But listening to Pligg scream about the dangers of overconsumption and the claustrophobia of post-industrial life makes me look around. The logistics required to bring this tour to bear staggers. I bring this up to the Harm’s Way merch guy after their set. He’s done a few Warped Tours.

“It’s crazy,” he admits. “But after the first one you figure it out.”

I restrain myself from haranguing him about load-in and load-out. I want the details he is likely unable or unwilling to provide to some rando. But my brain starts to attempt impossible ad hoc computations. I think about how much gasoline is required to pull off the tour — how many miles driven, how many vehicles, vendors, surprise expenses, the gas to fire up the grills to feed the bands, the merch guys, the sound crews, those responsible for setting up the stage — whatever other hands are held responsible for the invisible labor that brings this spectacle from city to city and eventually to Japan, where it will conclude.

Yet here are still more calculations: how much oil goes into our roads? Both for the machines and for the materials that make them and for the construction workers that build them and — though this happens less and less — maintain them.

And then to the wars that made and continue to make all this possible. As historian Andrew Bacevich states: “From the outset, America’s war for the Greater Middle East was a war to preserve the American way of life, rooted in a specific understanding of freedom and requiring an abundance of cheap energy […] Over time, other considerations intruded and complicated the war’s conduct, but oil as a prerequisite of freedom was from day one an abiding consideration.” This war, began late in the Cold War, hit its high notes when I was an adolescent, the same year I attended Lollapalooza, my eyelids blacked with eyeliner and my palm sweaty in my first love’s hand.

It was a war that, though to a lesser degree than the Gulf War a decade prior, and to Baudrillard’s observational credit, seems to have not existed. It was a war without casualties, as far as anyone back home could tell. Or rather, a war with statistics that represented casualties, but because of the media blackout on military coffins and war wounded and the strict management of embedded reporters, never felt real to the citizenry — no flash photography, nothing to write home about. And our film narratives, unlike those in the wake of Vietnam, have been successfully massaged by CIA “advisors.”

We look at the flowering of armaments and sectarian warfare in the Middle East and wonder how, why? When I was a young boy, first discovering punk and metal in my older cousins room in Lavonia, Michigan, he and I watched a VHS copy of the second Rambo movie. It takes place in Afghanistan during our proxy war with the Soviets. The film closes with Rambo and other happy warriors triumphantly raising their rifles in the sky. Lettering fades in: THIS FILM IS DEDICATED TO THE BRAVE MUJAHIDEEN FIGHTERS OF AFGHANISTAN.

Because, of course, we funded them to beat back the Soviets, to give the Kremlin “its Vietnam” when the USSR incurred into the region. Specifically, the CIA funneled money through Saudi spy master Turki Faisal — once a tutee of President Bill Clinton when they overlapped at Georgetown (Clinton tutored him for an ethics exam; Faisal received a B) — to acquire provisions for Osama bin Laden and his “brave fighters.”* American military history has, of late, been repeatedly, wistfully asking why our hands are on fire after we’ve pet a burning dog. If we want answers we likely need not look any further than over our shoulders.

But what would the answers really mean anyway? We’ve reached a point of stagnation in which no knowledge and no clear thinking animates coherent action or inspires meaningful results. There is no “and then.”

There is only “and now.”

…

The sun hoists high overhead. Its radiance borders on oppressive and I’m wearing pants like a jackass. Bottles of water are predictably overpriced.

Will and I walk around some more and end up seeing the Canadian pop-punk outfit the Story Untold. You can tell they rehearse all the time, practicing their harmonies. They’re not breaking the mold by any means, but punk stopped being about that a long time ago. It’s mostly settled into what I call “genrecore”: better and worse executions of familiar musical themes. The Story Untold play like they’re making a case for this idea. They even go so far as to play a pop-punk medley. The main song I recognize is Blink-182’s “Rock Show,” which details the agony and the ecstasy of meeting a summer crush at the Warped Tour. The album that spawned this single is Take Off Your Pants and Jacket; a tapestry of bygone pop culture unfurls before me. And what was I doing when that record came out? What was my life like?

I try to string together some kind of story.

When I was getting into punk, in the Internet 1.0 era, there was a word-of-mouth way to learn about it. You had to find other kids with messed up hair, bondage pants, band shirts; kids whose parents’ divorce had scoured their inner lives of safety and trust; parents who worked enough to provide a posh life for their children but too much to pay attention to them; kids who’d spent time in jail, been shipped off to military school and had come home every summer to evidence their underground education in upsetting and subverting every adult authority figure in a one-mile radius; kids who hung out in gas stations; kids who sleeved their arms with jelly bracelets or wore sweaters year-round to hide their scars or tract marks, or who put cigarettes out on each other and laughed; kids who, in other words, never felt the open pasture of the future roll out before them or who, even if it had, were so soured by the idea of having to wake up everyday that it hardly mattered.

These kids still exist. I see them everywhere around me in the Pepsi Center parking lot. Teenagers remain disaffected. But I don’t know if this “education” in the history of punk, metal, hardcore, goth, etc. still exists. There was a telos to it: you started with radio rock and moved towards edgier and often older bands in the “canon,” so to speak. Yet something like it must exist, because I stand there while Will jumps up and down, singing along, cigarette in hand, to every word of this medley. I know most of them as well. I smile and don’t know why. Is it recognition? Is this comfort? A profound alienation sets in. It’s not so much that this medley strings together a host of Warped Tour alumni and so presents a sweet excavation recent pop music history. It’s that everything collapses into now.

In his collection of essays on 9/11 and its aftermath, Welcome to the Desert of the Real, Slavoj Zizek draws a parallel between communist Cuba and the post-industrial North, or the West — whatever we mean by that now, whatever’s left of Christendom. Time has stopped in different ways for these locales: in Cuba, because of their use-value economy dedicated to maintenance and refurbishment and their limited access to the global market, it’s as if time stands still in the past — Canadian public transport buses gifted in the 1970s still carry people from place to place, cars from the 1950s still drive; in the North, the suburban project and a dedication (and the requisite spoils of hegemony for such a dedication) to constantly remake the world anew locks it in the present — all of history is repaved. The passing of time is but the continuance of persistent projects of ellison.

This hits me again as we make our way from watching the consummate showmen in Reel Big Fish play what’s likely the tightest set of the tour. They’re pros par excellence and their set drew the most diverse crowd of attendees.

…

…

Will and I camp at the other Monster Energy stage and wait for Sharptooth. On the stage adjacent, Senses Fail reaches the end of their set. We’re surprised by the lead singer’s naked vulnerability in dedicating a song to his daughter. He then informs the crowd that the band is in its 16th year of existence. Will and I look at each other.

“Holy shit,” he says.

“I remember hearing their first record when it came out,” I say.

And just when something is starting to feel like it has aged, has acquired some kind of sedimentation, the band launches into a cover of System of a Down’s “Chop Suey.”

Will passes me a cigarette, “They’re really doing it. They’re really playing this right now.”

“This whips.”

And from “Chop Suey” they move into a nu metal medley: Limp Bizkit’s “Break Stuff,” Drowning Pool’s “Bodies,” among others. The Time Warp begins afresh. Readers can refer to my earlier article on nu-metal and America for Invisible Oranges for better purchase of what this music signifies, the bygone era that belched it up; nevertheless, it sent me in a spiral deeper than The Story Untold’s medley if only by dint of repetition.

The crowd, midway through the medley, parts down the middle under the singer’s direction.

“It’s a Wall of Death,” I say to the open air.

But then something strange happens: instead of a wall of death, the crowd, as directed, storms towards each other and embraces. It’s a Wall of Hugs. I’m not too cynical for this — it’s touching. But then I find out there are also legal reasons for the affection — a few years ago, Oly Sykes of Bring Me the Horizon got in trouble at a Warped Tour date for instigating a real Wall of Death. The tour (read: Kevin Lyman) let Sykes know that in no certain terms would the tour be held liable — such stunts were verboten because the artists who inspire them will be held fully culpable for injuries and damage. It’s a catastrophe management strategy anyone who has seen footage of Woodstock 1999 can appreciate. But in hindsight, it’s also domesticating and therefore troubling. The long arm of the law tames everything it touches with its violence.

I remember, watching Senses Fail finish out their set, that Korn and Limp Bizkit are headlining the Warped dates in Japan. And now and now and now forever.

…

…

Sharptooth draws a small crowd — at first. For those not in the know, Sharptooth’s music is overtly political, often dealing with issues of misogyny, homophobia, and rape trauma. Their first record is good enough, but I had a feeling they’d be incredible live. I wasn’t wrong. I’ve never seen a more concentrated burst of energy, a more chaotic explosion of sound.

Lauren Kashan, the band’s lead singer, screams like she’s trying to bring the sky down to Earth. Between songs, she rails against society’s ills. Having gone to a fair number of punk shows that feature prolonged political rants, I was ready to cringe. But the band smartly plays instrumental interludes under Kashan’s diatribes about assault, coming out of the closet, solidarity, etc. She’s a rousing speaker. Truly unafraid and absolutely incandescent. As they play more and more people gather. The fellow feeling in the crowd is palpable — it’s the only moment of togetherness the day has on offer. The only thing that feels like a real connection.

Kashan, at the end, storms her way into the audience. Immediately, Will and I get anxious for the same reason. What man is going to ruin this by trying to grab her? I think to myself. But no one does. Instead, it’s as if there’s a forcefield of mutual respect around her. The women and queers in the audience claim the space around her and scream along.

Breathless, she finishes the set by telling us how much she loves us, how she’s willing to talk to any sexual assault survivors, any victims of our society’s myriad violent depredations who need a space to talk and to feel safe. She directs us to their merch booth where the band has a meet-and-greet planned in the next half-hour.

It’s one of the most moving concert experiences I’ve had to date. Uncool, unironic, unabashed. Their main song, “Fuck Donald Trump,” had exploded. It’s what brought the rest of the crowd over. But in the aftermath of their set, I’m troubled. It seems to me that we’ve hit a moment of decadence. I don’t mean this in a snooty, right-wing way. It’s a technical term, not a smear. We’re falling away, or at least think we’re falling away from old paradigms. Or perhaps we only hope we are. For good reason many of us desire this. Of course, this happens at a moment when the “old ideas” have refastened themselves to pubic life in a way more visible than many remember. Sharptooth’s demolition derby on the macho hardcore culture I grew up with is inspiring and invigorating. But what can replace the horror we have whole cloth? The Trump presidency signals a bleak right wing turn in America, but we’re kidding ourselves if we think it unique — slaves were, after all, once bought and sold in the White House. There’s little agreement on where to go next, on what’s even possible. America, never one to take seriously its history, has now experienced a foreclosure on the only real estate it ever wanted to have: the future.

These thoughts swirl as we leave the Pepsi Center. We bought water from one of the last vendors to have any before Sharptooth’s set.

“You guys are lucky,” the vendor told us. “I’ve only got water for another hour at most.”

We’re dehydrated and Will has work tomorrow. Will unfolds the schedule and reads off the headliners — Simple Plan and The Used among them.

“I’m not dying to see any of these bands.”

I agree. I’ve spent enough time re-litigating the Iraq War in my head all day. I don’t need to hear more songs that rocket me backward. Every Time I Die sounds across the asphalt as we wait for my car to cool down. I’m so hot and sweaty my brain misfires. I’m not sure what’s just happened to me, what I saw, what I’ve done, what I’ve heard. I’m woozy.

A vista opens before me when I wake up upon our re-entry into Colorado Springs. We’re cresting a hill on the highway and I see in the distance a series of disconnected subdivisions built into the mountainside. Will has been chugging Red Bull and Gatorade and listening to Lil Uzi Vert.

“Welcome back,” he says.

“How long was I out?”

“We’re still listening to the same record.”

“Jesus,” I say and point out to the subdivisions.

“I know.”

As we make our way back to New Mexico, I start to experience some clarity. In 1988, Joan Didion covered the presidential primaries, during which she saw the dawn of a new kind of Washington insider. She observes that “people inside the process, constituting as they do a self-created and self-referring class, a new kind of managerial elite, tend to speak of the world not necessarily as it is but as they want people out there to believe it is. They tend to prefer the theoretical to the observable, and to dismiss that which might be learned empirically as ‘anecdotal.’”

It strikes me that we’re experiencing a revenge of the “anecdotal.”

It was theorized that wealth would trickle down and promote new kinds of freedom in the form of consumer choice; it has been observed that it has not, and that it is not, respectively. It was theorized that America had the moral integrity and so the right to decide the world order; it has been observed that absent the former America’s “right” to police the world has revealed only its recklessness and general turpitude. It was theorized that the Obama administration ushered in an era of racial parity; it was observed that this could not possibly be the case. It was theorized that a politics of means testing and middle-management ethos were both what the American people needed and what they wanted; it has been observed that the American people neither needed nor wanted to nor could be moneyballed into magical thinking. It was theorized that the American Century bespoke a common purpose and grandeur to which all subscribed with not just unity but uniformity; it has been observed that this is simply not so. It was theorized that ill-gotten opulence could be enjoyed in perpetuity; it has been observed that it cannot do so without staggering inequality. And, in our longest lasting political fiction, it was theorized that freedom and equality under the law and the law alone is the truest justice possible; it was observed that this is a farce put on by a self-congratulatory ruling class terrified to admit that legal equality means next to nothing without material equality. After all, Bacevich, a conservative cited above, is at least honest enough to point out that there are in fact material “prerequisites” for American “freedom” as it stands today.

This disconnect between the theoretical and the observable has intensified the heritage of dishonesties that comprise American life. Thus we’re in the last days of a wind-tossed interregnum and time is running out. The end of the Warped Tour and my experiences in Denver make clear to me that my initial instincts were right. It feels as if there’s nowhere to go and little about which to be optimistic. And what’s the point of America without optimism? Our signature aggressive, cocksure smile must now strike the rest of the world as the rictus of the deranged.

The poet Anne Sexton once described life as the “awful rowing towards God.” But this implies directionality and we live in atomized time. “In atomized time,” Byung-chul Han writes, “all temporal points are alike. Nothing distinguishes one point in time from another. The decay of time disperses dying into pershing.” As Will and I re-enter Raton, the mountains near Taos no longer offer only smoke: a curled lip of wildfire rakes itself down the mountainside in the night.

Awful, yes. But not rowing. Just drowning.

— Emmet Penney

…

Become an Invisible Oranges patron.

…