Top 7 Most Metal Fantasy Premises

…

We’ve talked about genre fiction on this site before when Doug Moore listed the Top 7 Most Metal Science Fiction Premises. Today, though, we’re talking fantasy.

Fantasy has been a part of metal since its inception. Black Sabbath wrote about “The Wizard” on their debut album, for starters. That said, fantasy hasn’t always been very metal. After The Lord of the Rings was released, the genre was overtaken my similar stories: teams of good guys from disparate races unite and travel along distance to defeat some vaguely satanic, though less frightening, evil force. C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia with its aesthetic references to the nicest parts of Greek mythology and Christ metaphors, is even worse. No wonder Dragonslayer shortened their name to Slayer—fantasy was mostly safe and feel-good for a long time.

Not so much any longer. Mainstream fantasy has grown progressively darker, more violent and consequently more metal. I’m sure many of you either stayed up on Sunday night to watch the premiere of the sixth season of Game of Thrones, or hopped right onto Bittorrent to pirate it. The dire-but-exhilarating sensation at the core of extreme heavy metal lives on in that fantasy series. Last season’s penultimate episode “Hardhome” culminated in a 10-minute action sequence that seemed more like a high-quality black metal music video than something aspiring to be one of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films.

While we’re waiting for HBO to give us something equally metallic as “Hardhome,” here’s the seven most metal fantasy scenarios.

There may be spoilers below.

…

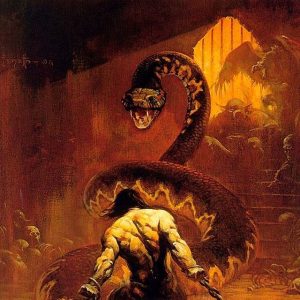

Celebrated pulp author Robert Howard’s Hyborea first appeared in Weird Tales magazine, the same publication that released much of Lovecraft’s Chthulhu mythos, and is the template for probably the most metal sub-genre of fantasy: sword and sorcery. Think burly dudes and curvy women in leather bikinis and you get the idea.

In Hyborea there is no objective good, but magic and the people who wield it are almost always evil. Life is incredibly hostile, and even for people with selfish but not always malicious intent—like mighty Conan—the only way to thrive involves a hefty amount of violence.

Conan remains a popular figure in metal circles, especially in the doom genre, whose slow tempos and bottom-heavy sounds reflect the tedious and grinding nature of Hyborean life. Several bands mine the Conan mythos for song lyrics, and one popular contemporary band is named after him. As influential, maybe, are the Frank Frazetta paintings which frequently accompanied Howard’s work. Several bands have also used Frazetta paintings as covers, including High on Fire whose red-hot distortion and tribal drum rhythm reflect the crass meanness of the Conan mythos.

Now where’s our doom band singing Red Sonja songs?

There’s no escaping Tolkien’s influence on heavy metal, particularly on European black metal. Bands like Burzum and their ilk idolize forests. Their music is as pastoral and repetitive as the lengthy sections of outdoorsy exploring in The Lord of the Rings. Likewise, Tolkien’s fascination with pagan European heritage and the obvious influence he drew from northern European mythology and Wagner’s Ring Cycle keep his work relevant in the pagan black metal scene.

That said, while Tolkien’s mythology is as multilayered and complex as the actual pagan folk tales he took influence from, his work is hardly as grim and advocating of inhuman evil as black metal is. Especially in Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s morality remains resolutely christian: Frodo resists temptation, Gandalf sacrifices his own life and rises from the dead, and eventually the forces of sin are purged from Middle Earth.

Dig a little, though, and you can find traces of a darker side to Tolkien’s mythos, particularly in the origin stories of Morgoth and Sauron in The Silmarillion. It’s no surprise both have bands named after them, but only Austria’s Summoning have dedicated their entire career to reflecting his work.

Some people call Glen Cook the father of “grimdark” fantasy, and it’s no surprise that some people use that same word to describe the most murky black metal. The world he presents in The Black Company and its related books is morally pitch black, even moreso than Hyborea.

Inspired by Cook’s time in Vietnam, the books detail the history of the titular brand of mercenaries, who routinely engage in ethically reprehensible acts like burning down villages, as well as a whole lot of treason. If someone were to graph the number of double-crosses present in a given set of novels, I’d bet that Cook’s would wind up at or near the top.

The Black Company novels balance two distinctly metal themes: on the one hand they detail the brutality of war and on the other the value of fraternity between the members of the company. The rivalries and humorous jabs between characters like the wizards One-Eye and Goblin make the cavalier violence of the series, often described in a clipped and sarcastic writing style, all the more charming. War metal musicians may dress more like the vaguely cro-magnon characters of Hyborea, but the spirit of the genre dovetails well with Cook.

It would be a grave error to compile a fantasy series list without some inclusion from the world of comics, and when it comes to longevity, few American fantasy graphic novels can stand up to the 28-years-and-counting run of Berserk.

Kentaro Miura’s Midworld is far from a unique fantasy setting—it’s mostly a stand in for Dark Ages Europe. Just look at the name. Originality is not the point for Berserk, or for many death metal bands. For a more creative—and intellectually stimulating—Japanese comic scenario, look to Hajime Isayama’s Attack on Titan.

What separates Berserk apart is its affection for gratuitous violence, and the truly disgusting designs of its villainous demons. The protagonist, Guts, cleaves armored enemies and massive monsters in two with a sword that’s nearly as big as he is—violence is more metal when it is ridiculous. His antagonists, the God Hand, are Cenobite-ish demons that convince people to massacre their loved ones in exchange for powerful demonic bodies of their own. Faustian bargains? Metal.

Brutal and satanic, Berserk is death metal to the core, especially when Guts begins to use the cruel berserk armor that gives the series its name. The one ring will always be the most iconic magical item that comes with a steep cost but the berserk armor is so much nastier. It gives its user incredible destructive power. If you break a bone while wearing it, it may just set that bone by driving metal spikes into your flesh. In Berserk the only way to beat the forces of evil is to become a killing machine and be “Pierced from Within,” which means that it’s ideally read while listening to Suffocation.

If Berserk is about the horrors of the Dark Ages, then George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, adapted for television as Game of Thrones, is about a failing renaissance. The Seven Kingdoms of Westeros are enjoying years of peace and increasing intellectualism at the beginning of the series, only to watch a sick game of multiplayer political chess thrust them back into war and famine.

Other series may be more violent (emphasis on may) but there’s never any real sense that Conan or Guts will die by the end. In contrast, Martin kills main characters with relish, and in metal no one is safe. Like Slayer, Martin shows no mercy.

The central question of the books is not, “who will sit on the Iron throne?” It is, “When will everyone realize that ruling does not matter when faced with a bunch of demons, their undead army, and the frigid climate apocalypse they bring with them?” As said above, the villainous White Walkers seem lifted wholesale from melodic black metal iconography, both in their affinity for sub-zero temperatures and their hatred of all living things.

Texan doom outfit The Sword were actually the first metal band that I’m aware of to use Martin’s work as lyrical source material (“To Take the Black,” “Winter’s Wolves,” “Lament the Auroch,” “The Maiden, the Mother, the Crone,” “Lords,” “The Black River”), but their warm and languid tone does not suit the series. The Immortal bard of Westeros, pun intended, is Abbath.

Restricting this list to literary worlds was tempting, but D&D’s shadow is just too large and too long to ignore. If Tolkien innovated the 20th century fantasy template then Gygax & Arneson perfected and codified it. Middle Earth was the first cheeseburger, but Forgotten Realms is the Big Mac.

But how did they make fantasy more metal? Putting aside D&D’s role in the Satanic Panic of the ’80s (very metal), the most evil thing about the RPG is its gallery of evil monsters. Especially at the onset, playable characters in D&D borrowed too much from Tolkien, but the Monster Manual is more cosmopolitan. The smorgasbord of beasts within draw from such disparate sources as middle ages folklore and H. P. Lovecraft. Better, it contains its own original oddities like the cycloptic and laser-tentacled Beholder.

When fantasy themed traditional and power metal bands try to invent their own fantastic settings, they invariably wind up sounding like highly customized D&D campaigns. There’s even metal songs about playing Dungeons & Dragons and even-even a band dedicated to that practice. Of course they’re called Gygax.

That said, when it comes to metal songs about D&D, Salt Lake city’s Visigoth did it best.

At its best, extreme heavy metal is potent because it is uncanny. It may present elements lifted from other perhaps more widely-appreciated genres, but in this musical context they provide no security. They are unnerving.

Few in recent memory know how to be unnerving and uncanny like China Mieville. His fantasy world Bas-Lag is as punishing as the remainder of this list, but pulls from a wider range of influences and is dedicated to discomforting weirdness. Like Tolkien, Mieville presents a panoply of nonhuman races, but Bas Lag’s are alien and unknowable: cactus men, women who have massive scarab beetles in the place of heads.

Bas-Lag, though, takes the class conscious London of Charles Dickens and the leery anarchist underground of G.K. Chesterton and stylized them into an industrial hellscape. In the wilderness, his monsters draw from Lovecraft not in tentacled design but in their unknowability: steampunk AI’s that hide in massive garbage dumps, playful demons of motion, and massive moths who feed on the dreams of sentient races.

But Mieveille’s most metal concept, and his saddest, are the Remade: criminals often guilty of petty crimes who are sent to punishment factories to have their bodies painfully altered. Mantis limbs and pistons replace arms and legs. A dead child’s tiny arms are grafted to his mother’s face like bull horns. Third-class citizens, the Remade are sentenced to tacit and sometimes-sexual slavery. The Remade are the modern music lover’s affinity for piercings, tattoos and modification turned into classist body horror.

Avant garde and progressive metal share with Mieville their affinity for splicing other genres into metal in the interest of keeping things off-kilter. In particular, San Francisco’s Giant Squid, shared Mieville’s interest in the human struggle as well as his fascinations with marine megafauna.