The Perils of Being Punk in Japan: Zainichi, Earthquakes, and the Police

…

This article is the first in an ongoing collaboration with Kaala, a website dedicated to documenting punk and heavy metal in Japan. Follow them here.

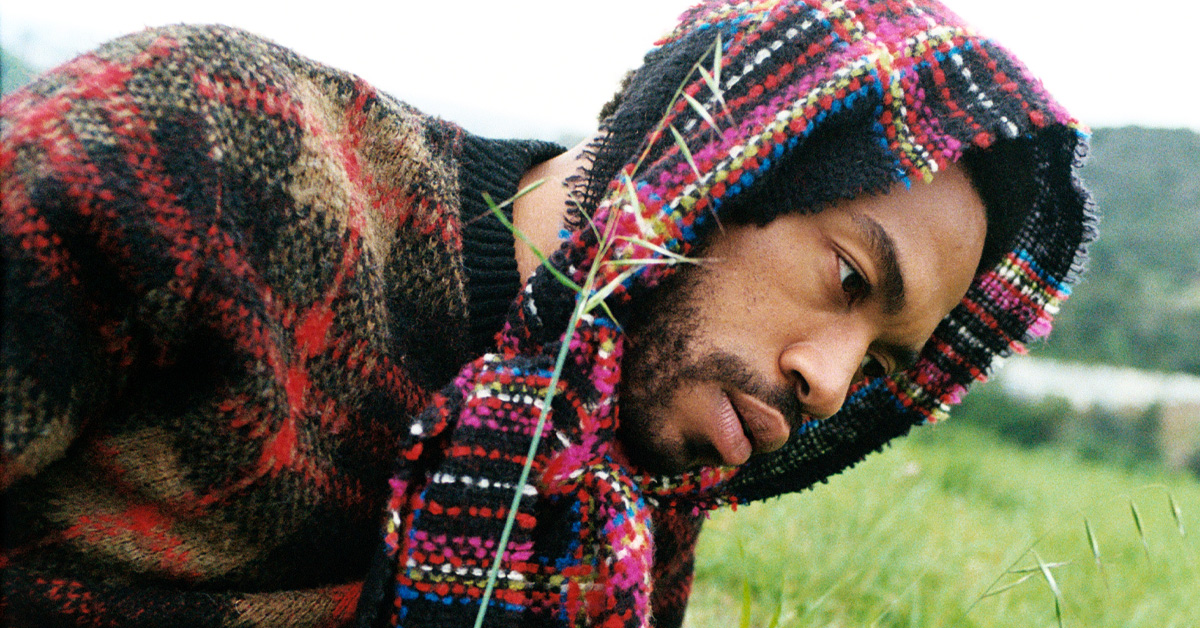

Words by Aaron Krall. Photos by Christian Ganum

…

“Outsider” is one of those terms that can’t — or rather shouldn’t — be used by oneself to describe oneself. There’s not much use in calling yourself an outsider if no one else is describing you as such, because it’s everyone else, not you, who gets to decide that. You don’t become an outsider by rejecting mainstream society, you become an outsider when mainstream society rejects you. Maybe because you make them uncomfortable or because you violate the standards everyone else works hard to maintain, but of prime importance here is the rejection, of you, by society. Those of us living in the west often see the term misused because, living in an ostensibly free and open society, there aren’t many outsiders.

Granted, there are groups both social and political and of varying sizes that have firmly fixed borders, but society has [Or had. – Ed.] been moving away from the formerly all-domineering codes and mores of the White Christian Man. There are more laws these days, but far fewer taboos that could possibly earn one expulsion from society (aside from the homeless, who, having committed the ultimate transgression of not having any money or a home, become essentially invisible). On the opposite side we have Saudi Arabia, which also doesn’t have many outsiders because extreme violations of social mores and attitudes — such as “being gay” or “not believing in god” — are punished with imprisonment or even execution. And in the middle of this strange horseshoe lie places like Japan.

During the Edo era of Japan (1615 – 1868) the Japanese class system “Shinokosho”, borrowed from Confucianism, could be roughly described as follows: at the top was the Emperor and his family, and below him was the Shogun (military commander) who did most of actual governing with individual warlords (daimyo) and their samurai below him. Underneath the warrior class one finds the peasants, mostly farmers and craftsmen, who were not generally wealthy but still had a higher position than the merchant class at the very bottom, who were viewed as a kind of parasite in that they did not produce anything but still somehow had money. Here the Shinokosho stops and what’s left are the outsiders, the buraku people: the eta and hinin classes, the untouchables and the un-humans. They were not included in the Shinokosho because they weren’t considered part of society. They were barely considered human.

The Meiji Restoration (1868 – 1912) put the real governing power back into the Emperor’s hands and dismantled the Shogunate, but a class system can’t be dismantled by an Imperial Decree. Class systems don’t exist solely on paper and have a nasty way of sticking around, and for our friend Nori the bassist of long-running crust outfit Life!, the extreme violation of social mores that resulted in him becoming an outsider was simply being born.

…

…

ZAINICHI AND JAPANESE PUNKS

Nori grew up in Chiba, Tokyo’s neighboring prefecture to the east, in a small, drab factory town that would be tempting to describe as “working class” except that this term doesn’t do the status justice. There isn’t a name in the west for the class into which Nori was dropped into from birth. “I was born in the slave class,” he told us with a bizarre calm. “Eta class, and the hinin class. Eta means ‘full of fears’ and hinin is ‘inhuman’.” Both of Nori’s grandmothers came to Japan from abroad around the time of the second World War, one from China and one from the northern part of Korea. This makes Nori a zainichi, a term that translate literally to “staying in Japan” but has become a shorthand way to refer to the ethnic Koreans and Chinese born in Japan. “With my family name, I can’t get a government job or work at a bank. I don’t even get the right to have a gravestone.”

Though he was born in Japan, as were his parents, due to his heritage Nori is not automatically granted Japanese citizenship. Thus, zainichi are not allowed to be publicly employed, since only Japanese nationals are allowed to be employed by the government, nor are they allowed to vote or claim government benefits. Zainichi have faced severe discrimination by Japanese nationals since the end of WWII, and exist in a strange in-between state in which they are accepted by neither the Japanese nor by Korean nationals. The economic fallout from this discrimination placed many zainichi families in working class neighborhoods where, despite sharing the shame economic hardships, they were still rejected by their neighbors, and it was in this environment that Nori grew up and became a punk.

Tall and thin and weathered by the hardscrabble life a wandering punk endures in this country, Nori has been playing in one punk band or another for over 30 years. He smiles a lot and laughs often, and one gets the impression that if he removed his shirt you’d be able to count each and every one of his ribs sticking out between his tattoos. He can’t remember exactly how many bands he’s joined in his lifetime but he’s certain it’s over twenty, and when Jharrod Meade-Frazier and I interviewed him earlier this year for Kaala Radio at Roppongi’s only death metal bar, Bar Brujeria, he said that it was all too obvious that he would become a punk. “My sister was really into foreign music and culture,” he told us. While growing up she would give him punk records, starting with the Sex Pistols in the late ‘70s and moving on to bands like Bad Religion, Minor Threat, and Bad Brains, and it was from these records that he began learning English by translating the lyrics into Japanese. In the few moments in which he wasn’t stubbing out a cigarette or lighting up a new one, he explained that “I wanted to know what they were singing about, why they’re so angry.”

A few months before his thirteenth birthday his sister’s boyfriend gave him a bass guitar, telling him it was a birthday present. “But it wasn’t a present,” he laughs. “They needed a bass player. [The next] month they had a gig, and they needed someone to play bass. That’s how I started playing bass in a punk band.”

According to Nori, many Japanese punks have the same story. “We had no choice,” he told us with the same strange calmness. “Be yakuza (gangster), or do something…draw something, or paint something, or play music or whatever.” He chose music, and once he started he never stopped. His opportunity to learn English in a more formal setting was hampered by the fact that he never graduated high school due to his band’s frequent touring, playing in abandoned warehouses and empty factories all across Japan. “When I first started playing more than thirty years ago, they had no place for punks so we had to play in like a factory or something,” he explains, adding that the police were frequently called in to break up the shows, leading to his first juvenile arrest for assaulting a police officer (there would be others). It wasn’t hard spotting undercover police, he told us, because “you can always see the difference, they have phone jacks in their ears and have Nike shoes or something. They keep taking photos of punks or anarchists or antifa people or whatever.” But this is, to him, a sign of their success, saying “There’s no point if you can’t be that threat.”

…

…

THE NAIL THAT STICKS UP GETS HAMMERED

In the west the threat of punk was neutralized by mainstream society co-opting the fashion and music of the original movement and creating a product safe for the population to consume, a costume robbed of any anti-capitalist/consumerism ideals or anti-government sentiment that had enough superficial resemblance to the real deal to fool the average consumer. The average American isn’t threatened by punk because to the average American it’s just another brand, and America isn’t threatened by brands. But though the recording industry is all too happy with watering something down and softening some edges to make a product more marketable, they’re also not afraid to court some controversy in the name of increased visibility. Anti-government and anti-capitalist messages and themes can still be found in some modern American music. So long as it abides by the FCC’s more and more lax broadcast guidelines, the government doesn’t really care.

Compare this attitude to that found in Japan. In December of last year I wrote an article for Kaala that explored the weird, muted, self-censored recording industry and strict, sometimes contradictory broadcasting laws. As I explained in the article, one couldn’t be faulted for assuming Japanese media enjoyed the same press freedoms found in the west since the Japanese constitution was modeled on the US constitution, but in practice this is simply not so. Music with a message critical of the government or even any specific individual will not only never be broadcasted, it won’t even be recorded by any label hoping to see some kind of return on their investment. Given that broadcast television is far and away the primary route through which the general populace is introduced to new music, and that CD sales are still the biggest profit-producing sector of the music industry, the result is any message critical of the government — or, again, even any single person in particular — will simply not be heard by the majority of the populace.

…

…

Unfortunately, this attitude is endemic to not just music but rather to all media in Japan, especially news outlets. As criticism of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s regime grows, so too does the crackdown on those unwilling to toe the party line. Last year three of the most critical news anchors were released from their posts from three different networks more or less simultaneously. This was done by the networks themselves, but no one doubts that it was orchestrated by the Prime Minister’s office because we all remember the recently-passed “secrecy law” and the thinly-veiled threats to reporters.

In the west we say “the squeaky wheel gets the grease”, but for the Japanese it’s “the nail that sticks up gets hammered”. This is not a society that rewards the bucking of trends and norms. Sometimes there can be punishments for those that try, but what will certainly happen first is an attempt to silence any discussion or protest. When PM Abe announced plans to “reinterpret” the part of the Japanese constitution that prevents Japanese military involvement overseas, something that the Japanese public has time and time again announced it does not want, massive protests erupted that received little or no media coverage. A man literally set himself on fire in front of the world’s busiest train station, and the first three stories I saw about it were from foreign news sources. Most of my co-workers had no idea it had even happened.

Earthquake, Fukushima, and Beyond

During the bubble days of the 80s and the subsequent economic collapse in the early 90’s Nori watched the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, noting the rampant gentrification and growing number of homeless. He started volunteering at NPOs that assisted people with severe disabilities, who like himself are also the subject of discrimination in Japan, but it wasn’t long before someone found a way to capitalize on even that basic service to humanity — in 2004, new legislation required a license to become a volunteer in this area, a license that costs a minimum of 70,000 yen (in USD, a little of six hundred bucks). To make matters worse, according to Nori the new organization regulating these fees was essentially a tunnel corporation (fraud) for some ex-Welfare Ministry member looking to make some money after retirement. There were demonstrations and protests, but to no avail and in the end, Nori told us, “I feel like we lost. We let them set that law.”

Due to media censorship of protests, the western world can’t be blamed for having an image of Japan as a conservative, docile, and homogenous society, and in many respects this view is not so inaccurate. A vibrant underground does exist, however, and it exists in opposition to the same forces that punks and anarchists and antifa oppose all over the world, though you’d never hear about it unless you come to Japan to witness it.

“So many foreign punks come here and ask why we don’t have a squat culture,” Nori told us. He’s one of the organizers for the punk festival Kappunk (warning: Japanese language only), held on a three-day weekend twice a year and showcasing over a hundred punk bands from both Japan and abroad, and he continually has to explain to foreign bands that the squat culture does exist in Japan, but it’s a little different and little more dangerous.

“My squat couldn’t last more than four years,” he told us. “The cops raided us in the end. 12 of us got arrested. Two of us got seven year sentences, and I can’t say more about two others because they’re still in court.” Despite the raid having been conducted in the ‘90s, litigation still continues. Nori himself had another warrant for his arrest first issued ten years ago, but after seven years the statute of limitations had it withering on the vine. “I’m not a bad person,” he protests. “I don’t do bad things. But still the government watches me.” In Japan, the danger of speaking too loudly about the wrong subjects is not insubstantial. During our interview we were forced to censor the names of certain leftist political groups because it’s unsafe to imply association with them.

Initially despondent by what he saw as decades of the softening of punk music both in Japan and overseas (which he attributes to a desire to attain more mainstream success), he was nevertheless heartened by the rising political awareness of Japan in general and Japanese punks in particular following the nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant in 2011. Immediately after the 3/11 earthquake, the Japanese underground activated itself and went to help. Four days after the disaster at Fukushima Dai-ichi, Nori was in Fukushima assisting in relief efforts and sneaking past the boundaries put in place surrounding the areas near the damaged plant to search for both survivors as well as the bodies of those not so fortunate (Kaala founder Matt Ketchum, who had a front-row seat to the tsunami when it washed away his apartment building and most of his town with it, told me he heard news of punks arriving with food and blankets days before the Japanese Self Defense Force showed up).

Presently, he sees modern times as a new era for the underground Japanese punk scene. “We had so many struggles, but it’s easier now. I feel like we’re starting a new era. It used to be… punks got separated. Divided. The economy got so low, and many just gave up.” But now he admits to seeing more unification between previously divided scenes, as well as something like a political reawakening, or perhaps just a remembering of values the scene once had.

…