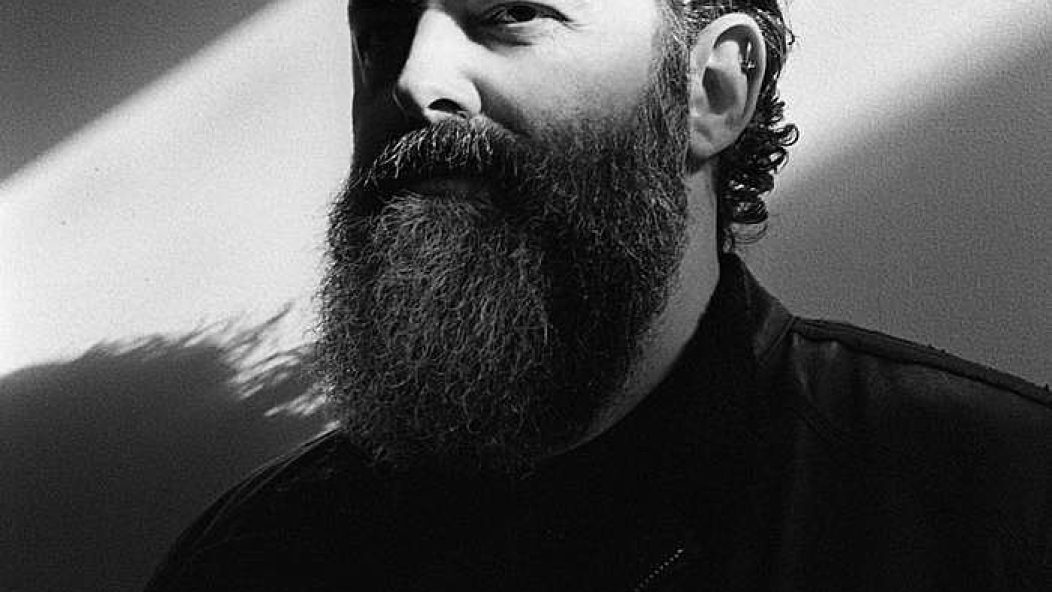

James Plotkin's Uncompromising, Experimental Vision (Interview)

Khanate surprised the metal world last month with the release of their first full-length record in 14 years, To Be Cruel. Calling something this abrasive “an instant classic” would be silly, but for musical masochists and appreciators of envelope-pushing, it’s an immersive, caustic, and ultimately cathartic journey through pain.

The band often get called a supergroup for the members’ impressive CVs. Vocalist and lyricist Alan Dubin shrieks for Gnaw; drummer Tim Wyskida plays with Blind Idiot God; guitarist Steven O’Malley is widely known for his work with Sunn O))). Meanwhile, Khanate’s bassist, synth player, and producer James Plotkin has amassed a truly staggering Discogs page of his own. Spanning from parodic grindcore to ecstatic experimentalism, Plotkin’s name appears on countless works of extreme music for his mixing, mastering, synthesis, multi-instrumental songwriting, and improvisational risk-taking.

…

…

“I got into heavy and hard rock pretty early,” Plotkin says, citing Maiden and Metallica as formative influences. He grew up in a family of musicians and experienced golden-era thrash, and later early grindcore, as an “epiphany.”

“I’d be in my parents’ basement with a four-track just throwing down ideas. One thing led to another, and I met some kids at school I wanted to try and form a band with—that became Regurgitation.” The band landed on the influential Speed Metal Hell Vol. III compilation when Plotkin was still in high school.

A friendship with Napalm Death‘s Mick Harris and tape-trading with Dubin helped Plotkin open the firehose of underground music, including hard-to-find releases from Europe. “I was devouring music at a ridiculous rate when I was kid,” he says. “I’d exhaust one genre and move to the next, so it was only a matter of time until I got into electro-acoustic, concrete music, that type of stuff.” Regurgitation evolved into OLD, who rapidly shifted from tongue-in-cheek grind to jazzified industrial music on Lo Flux Tube, which featured guests including saxophonist John Zorn on the title track.

…

…

Importantly, Plotkin wasn’t interested in hewing to orthodoxy or making it big. “I didn’t really have any deterrents as far as mixing genres,” he says. “Financially, it’s probably not a great way to approach music, but it’s one of those things where you just keep doing what you’re doing, and eventually, people notice.”

Yet Plotkin has made a living on music while maintaining a consistent output. While working with a variety of collaborators—he cites his improvisations with Paul Nilsson-Love and electronic excursions with Benjamin Finger as particular highlights—and forming Khanate, Plotkin began mixing, remixing, and mastering for other artists with a similar sensibility.

“When I got a computer in 1999, I was relatively inexperienced with stuff outside synthesizers, but as soon as I worked out a digital workstation and could mix, arrange, record and do everything from the comfort of my own home, I was basically open for business,” he says.

From his Plotkinworks studio, Plotkin now mixes and refines two to 300 recordings a year, keeping track of them all on a pad of paper at his desk. He says remixing is particularly enjoyable because “it’s limitless what you can do with someone else’s recording.”

“I really enjoy being that outside set of ears that can either summarize or consolidate all the ideas from the artists and come up with a sort of grand scheme or maybe a solid whole from everything floating around within a recording,” he says.

In the mid-’90s, Plotkin collaborated with Harris, who’d left Napalm Death, and others like Mark Spybey on cinematic one-off albums. Doom and drone were gaining currency at the time, and a desire to experiment with those textures led Plotkin, Dubin and O’Malley to form Khanate. “As usual (with) whatever we were getting involved in, we wanted to experiment heavily, otherwise what’s the point?” Plotkin says. “I really don’t like homages all that much. It has to be new and exciting or it doesn’t hold my interest.

“I welcome basically any process as long as it’s not something like a standard songwriting process where you’re bouncing ideas back and forth for typical verse-chorus stuff.”

Certainly no one would accuse Khanate of favoring pop song structures. From their self-titled debut’s sludge-infected doom to To Be Cruel‘s relentless creep, the band have consistently favored slow builds and lingering chords. To Be Cruel in particular seems to exult in torturous slow builds nursed with feedback, Dubin’s vocals direct and searing.

To Be Cruel emerged organically from recordings by O’Malley and Wyskida that were “very Khanate;” the record came together piece by piece over the course of more than five years due to the four members’ different locations and packed schedules. Plotkin sounds pleased with the results of the long process: “We took the band to a place we envisioned it going in the past. It was really just a matter of coincidence that it all came together this way.”

Plotkin and his various friends and collaborators have consistently pushed music to its limits with their work together. Whether it’s the frenetic mathcore madness of Phantomsmasher, the blistering experimentalism of Khlyst or Plotkin’s mesmerizing solo releases, each pushes into unexplored territory.

…

…

Alongside a docket of mixing and mastering projects, he plans further collabs and the small-scale release of some Buchla synthesizer compositions in the next year. Khanate has planned a tour next year in support of To Be Cruel, possibly beginning in Europe where Wyskida is based. Though much is dependent on members’ schedules, Plotkin feels the time is right for some live dates.

“The world’s a fucking disaster right now,” he says, “and Khanate makes disastrous music.”

…