So Grim So True So Real: The Dillinger Escape Plan

…

Music enthusiasts need a new way to think about artist discographies. Proliferating top-to-bottom lists impose the idea that a band’s body of work ought to be listened to in a certain order, and too often reinforces the notion that every band only has a handful of albums worth exploring, which leaves great music underappreciated.

So Grim, So True, So Real offers a new way to think about a given band’s discography. In this feature, we will highlight first, the low point in a band’s body of work (So Grim), and then the album which, to the best of the IO team’s estimation, most people hold in the greatest esteem (So True) and finally one album which holds up as the best listening experience, regardless of what fans and critics insist (So Real).

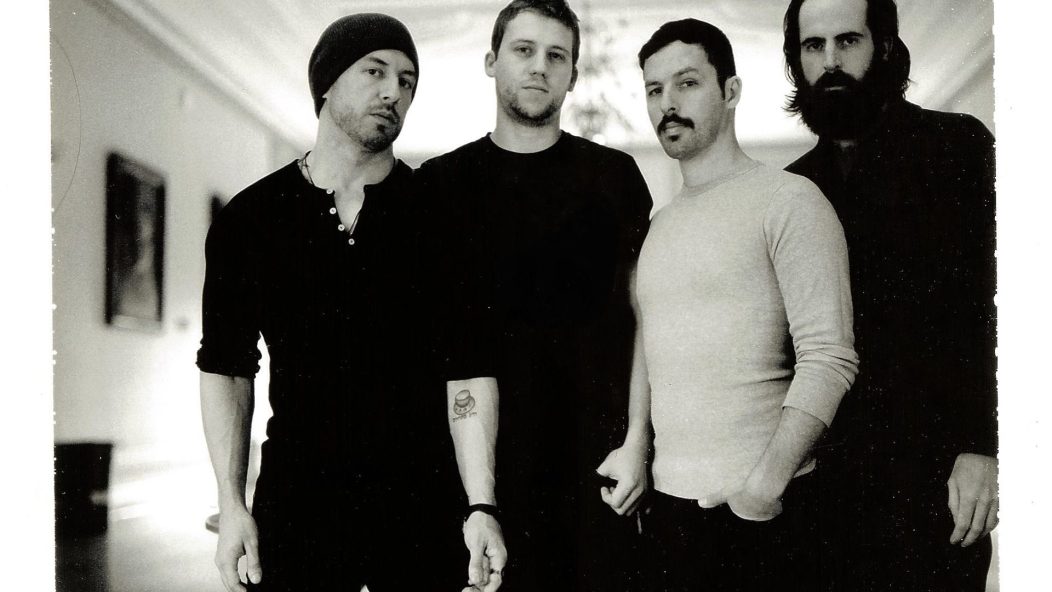

Since it’s Dillinger week, the first So Grim, So True, So Real covers New Jersey mathcore and progressive metalcore outfit, The Dillinger Escape Plan.

…

…

…

So Grim: Ire Works (2007, Relapse)

The Dillinger Escape Plan ending their recording career in 2016 offers the silver lining of a near-perfect discography. The band never released an unlistenable, or even unpleasant album (at least to those who find their jarring musical style pleasant in the first place). The worst they got was comparatively uneven and sometimes-forgettable, IE 2007’s Ire Works.

That said, it feels out-of-place to call an album that includes such huge and iconic songs “forgettable.” Dillinger did their own trumpet-accented take on Motorpunk with “Milk Lizard” as well as a straight-up pop rock anthem on “Black Bubblegum”, which have remained cornerstones of the band’s setlists from there on out. Maybe more indelible, Ben Weinman made the most of his friendship with Mastodon’s Brent Hinds, as well as their shared Relapse Records connection, on “Horse Hunter.” Each of these songs packs huge hooks.

The trouble is, their addictiveness comes at the expense of some of the band’s essential mathcore groundwork. Songs like “Party Smasher” and “Lurch” sound like B-sides from earlier albums when put before and after such tunes. Maybe worse, the aforementioned huge singles themselves can feel like afterthoughts when the lion’s share of the creativity went into the suite of intellectual dance music flirtations that occupy the middle part of the album.

The electronic bits have their own downside. Even though “Sick on Sunday” “When Acting as a Particle” and “When Acting as a Wave” obviously took much effort to arrange, their abbreviated song lengths make them seem like sketches rather than fleshed-out ideas. If Miss Machine was the sound of the band finding their voice by pursuing out-of-genre influences, then Ire Works was them following those influences just a little too far.

…

…

…

So True: Calculating Infinity (1999, Relapse)

Of course the debut album by a genre-defining act comes practically shrink-wrapped in cultural capital. That no other Dillinger album features founding vocalist Dimitri Minakakis further ensures that no dyed-in-the-wool Dillinger fan, especially those around when Calculating Infinity was new, will accept any substitute. Their devotion is well founded. Strands of this record’s DNA manifests in a who’s-who of scarequotes-important metal and hardcore acts today. Some of those descendants remain almost painfully obvious, such as Car Bomb. Others, like Deathspell Omega, remain one step removed, but still refer back to the off-kilter blueprints laid out in songs like “The Running Board.”

Calculating Infinity is a masterpiece not just because it typified jazz-ish and atonal metal guitar songwriting in the 20th century, but also because it commands atmosphere in a way most of its admirers forget. The middle section of “Destro’s Secret”, for example, is still truly creepy. For further mind-bending, keep in mind Weinman and then-compatriot Ben Benoit got their guitars to sound that mean in standard tuning.

Calculating Infinity does however, like Ire Works, suffer a bit from the overpowering catchiness of its opening salvo of songs. The biggest culprit, “43% Burnt”, for better or worse, sports one of the most iconic jumpdafuckup mosh riffs in heavy music. Dillinger, and mathcore in general, existed in part to subvert the jocky machismo that continues to define much typical hardcore, but “43% Burnt” is one of the best beatdown hardcore songs there is, even if they play that riff in odd time. It’s the riff that jump-started their career as a touring act, but it’s also the riff that makes it hard to hear the rest of the record. Paying attention to the jazz noodling of the title track becomes a difficult task when the listener knows they could just skip back six times for another meaty round of “BREE-DEE-DEE-DEE .. Chunchun!”

…

…

…

So Real: Miss Machine (2004, Relapse)

Clean singing, an overt interest in mainstream alternative rock and a lead singer swap guarantee that Miss Machine will never achieve the esteem of its predecessor, even though Calculating Infinity already hinted in this direction, even though those alt rock influences refer in large part to Mike Patton, who joined the band briefly in the interim, and even if Dillinger recorded a Justin Timberlake cover prior to the album’s release. More reasonable older fans will say, rightly that Miss Machine broke no new ground in a world where Calculating Infinity changed the hardcore market. They will also say that the band from 2004 on is just not “their Dillinger,” which is true.

None of that matters, though. The Dillinger of 1999 was long gone in 2004. The Dillinger of 2004 was a different band, one that didn’t change the game but did write a ton of great music, and this is the first and best iteration of that band. The band retiring at the end of this month? The band which rests on the axis of Greg Puciato and Ben Weinman? That is the real Dillinger Escape Plan, and their debut album is Miss Machine.

Which isn’t to say that Dillinger abandoned what they built over five years prior. This album’s first half remains violent throughout. Most of Miss Machine sounds like the best parts of Calculating Infinity with a smidgen more attention paid to choruses, though none of the neurotic preciousness of other bands that tried the same idea on like, say Norma Jean, Daughters or The Number Twelve Looks Like You, each of which dropped debut albums in 2002 or 2003. Songs like “Sunshine the Werewolf” emphasize stabbing rhythmic bursts. By that time most of Dillinger’s original compatriots had either broken up (Botch), or embraced melodic rock music entirely (Cave In). Converge were chasing their own high-speed emotional noise rock rabbit. Dillinger were just plain meaner on Miss Machine.

That meanness comes from Puciato, a more talented vocalist than his predecessor, Dimitri Minakakis. The virulent masculinity that Minakakis played with on “43% Burnt” comes home to roost even more so on “Phone Home”. Here, fresh and hungry, his screams embody the kind of neurotic, senseless fury that only people in their early twenties can muster, and most of that ire translates in his melodic singing as well. On maybe Dillinger’s best song, “Setting Fire to Sleeping Giants”, Puciato slides between both vocal lines with no friction. His vocal range let The Dillinger Escape Plan take what they had already mastered and apply it to more colorful and diverse songs.

With Puciato as the secret ingredient Dillinger pried their sound wide open in a manner not unlike the way ballads took Metallica from Kill Em All to Ride the Lightning. The band never made another leap between records so dynamic (even though most of the albums following were nearly as good), which is what makes Miss Machine the most real album in The Dillinger Escape Plan’s discography.

…