So Grim So True So Real: Lamb of God

…

So Grim, So True, So Real offers a new way to think about a given band’s discography. In this feature, we will highlight first, the low point in a band’s body of work (So Grim), and then the album which, to the best of the IO team’s estimation, most people hold in the greatest esteem (So True), and finally one album which holds up as the best listening experience, regardless of what fans and critics insist (So Real).

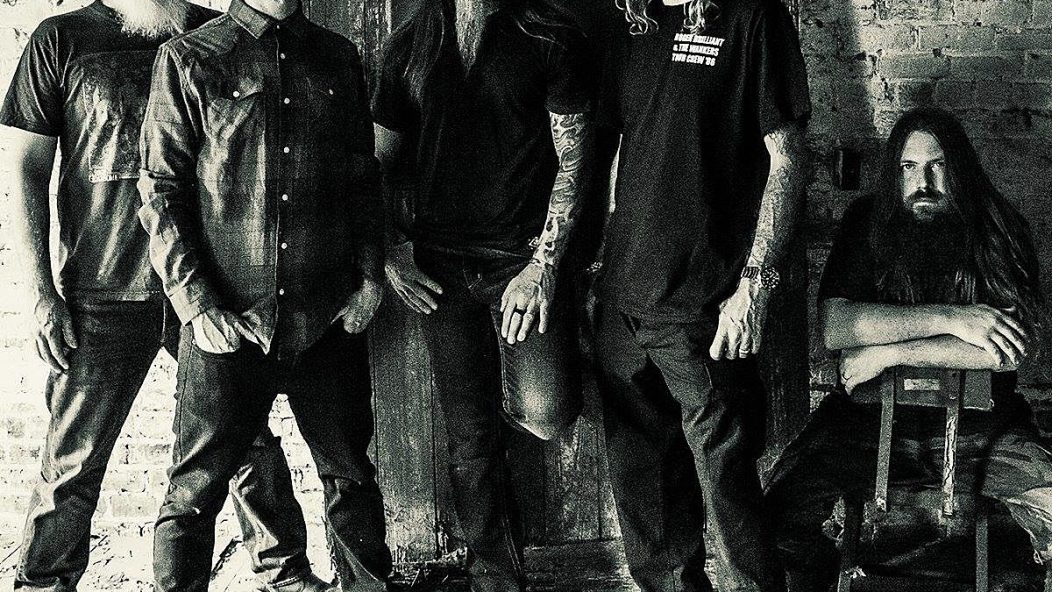

It’s been 17 damn years. From the dingy basements of Richmond, Virginia to high-gloss magazine covers. From relative obscurity to household name. From cramped venues to grand stadiums. Through eight studio albums, three documentaries, countless worldwide tours, and a litany of front-page drama, Lamb of God have seen and done it all. They’ve lived it all, right in plain sight, and hundreds of thousands of fans have taken part vicariously.

The band and their albums need no real introduction; it’s the fan dialogue which is of most interest. More often than not, people argue about which Lamb of God album is the best, not the worst (this is usually a good sign for a band). But to assume that Lamb of God has a singular “best” album is also to assume that Lamb of God is, once stripped down, a single-focus band. The sheer stylistic breadth across their albums alone demonstrates them as multifarious, dynamic, and ultimately trend-setting. Each Lamb of God album is its own distinct expression of “current” metalcore.

Yes, Lamb of God got wildly popular, and this undoubtedly affected their music — whether positive or negative is entirely subjective. The point is that they quickly became a bar against which most other metalcore was gauged. Expectations ran high (maybe too high), and the band grew more composed, professional, and produced. Again, it is subjective whether this was an improvement of their overall sound: the cleaner shift in Randy Blythe’s screaming style, the growing reliance on chords over single-note riffs, and the departure from a raw, gritty aesthetic for something more honed and polished.

Like most, I’m biased. While Lamb of God wasn’t the band to get me into metal, they were the band which first truly nurtured my love for it. Certainly, learning their songs as a budding guitarist helped. Lamb of God was also my first (real) metal show, and I fervently cherish those memories. The band for me has real and true personal meaning, and there’s no detaching from that. Nor would I want to.

That said, my analytical side still has a say in the matter. My tastes have changed wildly since my Lamb of God days. I still enjoy my favorite Lamb of God albums, but not in the same way that I used to. There are pros and cons to this, but suffice it to say that I’m slightly removed from the band’s scene nowadays. For the pseudo-objective purposes of the below analysis, this should be beneficial; however, related to how Lamb of God makes me feel, I may have grown slightly cold.

…

…

So Grim — VII: Sturm und Drang

What happened? Over the years, Lamb of God got more melodic, more groovy, but less bombastic. That would have been fine had: a) the progression stopped or diverted somewhere along the way, or b) their songwriting not originally grown out of belligerent forcefulness and “fuck subtly.” Credit where it’s due, though, VII: Sturm und Drang (2013) was at least exploratory for the band, but what they found was ultimately as underwhelming and gimmicky as the Chino Moreno cameo on “Embers.”

What’s more, “Footprints” has a nifty intro, but that track is immediately ruined by the abysmal clean vocals on the following “Overlord.” For a moment, “Anthropoid” seems like a winner with Blythe’s initial raspy growls, but the song quickly dissolves into a sing-songy, tiresome bore with its unchanging pace and monolithic drum track. And the track “Erase This” actually has literal meaning. Moments do arise where Mark Morton and Willie Adler’s guitar riffs are celebrated and given front stage, but too often they’re in super-repeat chorus mode and overpowered by Blythe’s bark. Chris Adler now sounds like he has six appendages when he really only needs two.

None of this means that VII: Sturm und Drang isn’t a true Lamb of God album — it does have all the necessary, branded parts, they’re just overcomplicated and disarranged in a mire of add-ons/touch-ups that’ve increasingly loaded down the band over the years. Perhaps Lamb of God were overwhelmed by the thought that by carving out a distinctive sound that they’d be resigning themselves to making the same album over and over again. Or, maybe they really tried to reconnect with things of yore only to find them uninspirational, or maybe even daft. Whatever the cause, VII: Sturm und Drang was a huge reach, but also a huge departure.

No matter how new you try to be, or how, the past always presses its influence. The preceding Resolution (2012) still had decent tiebacks to Wrath (2009) which in turn saw significant inspiration from not the often controversial Sacrament (2006) but rather Ashes of the Wake (2004). However, Resolution (while still a fast record) was ultimately too far removed from the band’s incredible initial burst of energy to adequately nurture VII: Sturm und Drang. Maybe a track like “Delusion Pandemic” (at least the first half) could stand in opposition to this idea, but even as a full exception it doesn’t change the whole.

…

…

…

So True — Ashes of the Wake

Ashes of the Wake contains Lamb of God’s most accomplished work and was their leap into the big leagues. It also remains their most memorable: moments like the “vomit riff” on “Hourglass” or Blythe’s soapbox kickoff to “Omerta.” Each song had distinct character and a special hook. This album was unabashedly groovy, full of vibe, especially with the blossoming of Adler’s footwork. The band had matured significantly (e.g. fewer breakdowns), vastly widening its overall appeal.

“Matured” means that Lamb of God had become more technical, more polished, and — to some disdain — less raw and gritty since As the Palaces Burn. Still wholeheartedly riff-based, though, Ashes of the Wake explored smoother transitions, groovier melody, and more complex song structures than prior releases. It undoubtedly contains pure in-the-pit-let’s-fuck-this-shit metalcore, true to the band’s form and image, sans posturing. Lamb of God would have withered and died had these tracks not stirred moshpits live… and just as quickly had they not been jammable on record too.

To their benefit, Lamb of God explored additional dynamics on Ashes of the Wake but didn’t forget to pay homage to their history. This resulted in arguably their best-rounded album to date: “Laid to Rest” was undeniably an instant and modern classic (the most number of plays on Spotify of any Lamb of God track), while tracks like “Blood of the Scribe” and “Break You” harked back to the somewhat more unhinged New American Gospel (2000) days. And then there was the quirky and fun “Now You’ve Got Something to Die For” which pretty much spoke for itself.

Truth is about balance and finding middle ground. Any downsides to the polishing/shaping up Lamb of God did with Ashes of the Wake are overruled by the superb quality of its songwriting and the ferocity of its execution. And it’s not like they cleaned up and started wearing suits. It’s certainly the most likable/relatable Lamb of God album, written by a band who at that point had proven a lot, but not quite enough. That’s not to say anything negative about the preceding As the Palaces Burn (2003) (spoiler alert for below) — as their breakaway album, it needed a follow-up album for meaningful context. What As the Palaces Burn received as a successor was, ultimately, mightier… but maybe that’s not the whole picture.

…

…

…

So Real — As the Palaces Burn

If Ashes of the Wake is essential Lamb of God, then As the Palaces Burn is the essence itself. That is to say: everything that makes Ashes of the Wake “so true” was first made “so real” on As the Palaces Burn. The earlier album pooled the raw ether from which a thriving life-force was summoned — if one would argue that Ashes of the Wake had better material, another could equally argue that As the Palaces Burn had more soul. To wit, As the Palaces Burn is the “naked” Lamb of God album, i.e. the least embellished but the most arousing.

It was with courage that Lamb of God departed from the prototypical New American Gospel (2000), the album whereon the band augmented their existing pit-ready groove with some modicum of technicality. Their work as Burn the Priest was clearly a blueprint, but perhaps too much so: they just weren’t where they could have been in terms of writing crisp but complex metalcore songs. Three years later, a balance was struck between the Burn the Priest raw ether and Lamb of God’s newfound skills/chops; as such, As the Palaces Burn would irrevocably define the band by mating their roots with their aspirations.

As the Palaces Burn is about unhinged energy: excessive triplets, crunchy breakdowns, Blythe’s cigarette vocals laid bare, and Devin Townsend’s raw but punchy production (the 2013 reissue/remaster “ruined” it). Tracks like “Ruin” ruined faces with its no-fucks-given intro and hyperspeed breakdown. Like the other nine tracks, it was proudly hyperbolic and unashamedly reliant on hooks, grabs, and kicks. These were the days of God Forbid’s Gone Forever, Shadows Fall’s The War Within, and Trivium’s Ascendancy: tough contenders for sure, but diluted compared to the razor brutality of As the Palaces Burn’s “Boot Scraper” or “Blood Junkie.”

For all this talk about rawness and aggression, Lamb of God even demonstrated they could do drama. The album’s poetic closer “Vigil” begins cleanly but soon breaks into distortion with Blythe screaming, “Our father, thy will be done!” — a righteously cool move. It then rises like a ballad and culminates with a machine-gun breakdown and Blythe spewing out, “Smite the shepherd and the sheep… will… be… scattered!” Sadly, this sheer level of pantomime was never sustained past that moment — Lamb of God made attempts to rebirth it, but found themselves too contained and constricted by what they thought was interesting versus what they thought was extreme.

The idea of “so real” is that the listening experience matters, inasmuch as it best approximates the experience of seeing a band live — not necessarily just in production value, but in the palpable energy of expression, or whether it sounds better the louder its played. In many ways, Ashes of the Wake is more fully featured album, but those features would mean nothing without the fury and fire it carried over from As the Palaces Burn. What Lamb of God found on As the Palaces Burn was perhaps one of the freshest (but most energetic) takes on metalcore in its history, whereas Ashes of the Wake probably dictated it more clearly. Nevertheless, both serve the Lamb of God story equally well: one speaks to the mind, and one speaks to the heart.

…

…