Slayer's 'Reign in Blood' Turns 30

…

Metal fans worship. We call our most beloved songwriters metal gods, even though a distaste for religion is one of metal culture’s more unifying sentiments.

Slayer do not worship. Hatred for religion is the most central theme in their music. And thirty years ago today they released their most popular indictment against god, Reign in Blood.

People worship Reign in Blood. Ultimate Classic Rock put it in their (chronological) top 50 metal albums of all time. Guitar World called it one of the eleven most essential thrash records, while Decibel put it at number two. Metal Storm called it the 26th best metal record ever. NME readers voted it in the top 20 metal albums ever, while Rolling Stone’s readers put it at number 6. Metal Rules put it at number five. Loudwire called it the fourth best metal album of all time. Kerrang called it the heaviest album ever released (though only 27th best metal album ever). LA Weekly called it the best metal album ever.

This worship is misguided. In true antichristian fashion, Reign in Blood is a golden calf that deserves to be slaughtered, or at least bled out a little.

On Reign in Blood Slayer drew a perfect thin, red line. It’s a singular record with a singular purpose: adrenaline. They embodied it, they produced it. These songs increase heart rates. In effect the music sounds simple-to-understand and direct to the point of mathematical elegance, which is admirable in the abstract.

The trouble is the various decisions that Slayer made in order to create that thin red line: Tom Araya’s consonant-riddled vocal bark, abbreviated song lengths, Kerry King and Jeff Hanneman’s tremolo-bar destroying dive-bomb guitar solos, every bugfuck nuts fill Dave Lombardo performs. Every single one of those individual ideas is more interesting than the songs they are in. Reign in Blood is, in every sense, much less than the sum of its more-interesting parts.

Sometimes everything does come together as on the first and last songs. “Angel of Death” is as close to a platonic ideal opening track to an extreme metal record as I can think of. “Raining Blood” balances rhythmic precision and dramatic tension in a way that I’m not sure I’ve heard in any other song, and its crushing finishing breakdown probably established that trope as bog-standard for almost all metallic hardcore to come. But the success of “Angel of Death” and “Raining Blood” only makes the rest of the songs’ shortcomings more evident. Bookending the album with these tracks gives context to the morass in between, but the remaining eight songs don’t pack near as much replay value.

Instead of emphasizing choruses and melodies, Reign in Blood relies on a series of memorable moments to carry listeners through that middle portion of the record. Usually these big instants involve a tempo change, as in the quarter-time breakdown that closes “Necrophobic”, or an emphatic vocal hit like Arya’s scream at the end of “Reborn”. At their best, these one-off hooks are both, such as the momentary rest at the end of “Postmortem” where Arya manages to sandwich “I’m only after death” into one second of space (that’s one more syllable than “you suffer, but why?”).

Lots of these moments come either at the beginning or the end of tracks, so each song repeats the same structural trick that the album does: shocking open, memorable end, and a whole lot of velocity in-between.These non-traditional rock structures, redirect the listener’s emphasis from the middle of a track to the transitions between them.

Given that, I’d like to think of Reign in Blood as progressive. At their best, such as the finale of “Angel of Death”, King and Hanneman’s solos can take on the freak-out qualities of a great jazz fusion solo. In the same way that, by eschewing vibrato, Miles Davis gave his trumpet a human vocal quality, King and Hanneman’s dive bombs can feel like the wailing of an opera singer, a natural extension of Araya’s Halford-ish howls.

In these instances you can hear them reaching for something beyond what they were playing before, beyond what metal had been in the past. Those moments where they eschewed rock and roll song structure entirely informed almost all extreme metal that followed them, but most clearly the first wave of Floridian death metal bands, who all more or less started out by rewriting this record.

…

Slayer on TV in 1986

…

I can’t though. In interviews from that time, Slayer come across as almost ascetic in their musical conservatism. During promotion for the album, Araya told Metal Forces that he thought the album is ”a lot more like Show No Mercy than Hell Awaits.” That same year, Lombardo told told Gary James “You know how we hold on to the early fans? We don’t change.” The quantum leaps forward that Slayer made on this record then, were probably accidental or at least incidental.

Purposeful or not, the advancements made on Reign in Blood can’t be attributed just to Slayer. The band’s fifth Beatle in 1986 was now-famous producer Rick Rubin, who gave the group an unprecedented and hard-hitting production job. Where Slayer’s second record, Hell Awaits, still sounds sludgy and amorphous, Reign in Blood is sharp and clear. Its guitars roar, its drums pop and Araya’s vocals take a central part of the sound without detracting from the record’s atmosphere. If that sounds familiar, consider that this sound remains the template for most extreme metal records with high commercial ambition.

…

…

Rubin was in a unique position to produce Slayer at the time. Coming from a background in hip hop, he was probably most well-known for his collaborations with Run-DMC, but woudl become ubiquitous a month later the mastermind behind the first Beastie Boys album, Licensed to Ill. His admiring outsider’s perspective led him to accentuate the most aggressive parts of Slayer’s sound. Rubin’s previous projects involved taking the sound of classic hard rock riffs and retrofitting them into a hip hop template. Fresh out of a scrapped recording session with Aerosmith, Rubin may have done the inverse to Slayer: Araya’s rapid fire and percussive vocal delivery on the record evokes hip-hop as well as hardcore.

But where hip-hop and hardcore praised realism and storytelling in their lyrics, Slayer doubled down on the violent occult lyrics that their peers were already moving past. Yes, “Angel of Death” describes a real person, but what use does discussing Josef Mengele serve in 1986? Some social commentary crops up in “Epidemic”, but otherwise, much like the album’s art, Slayer’s mishmash of spooky poetry amounts to dick jokes told with absolute seriousness.

…

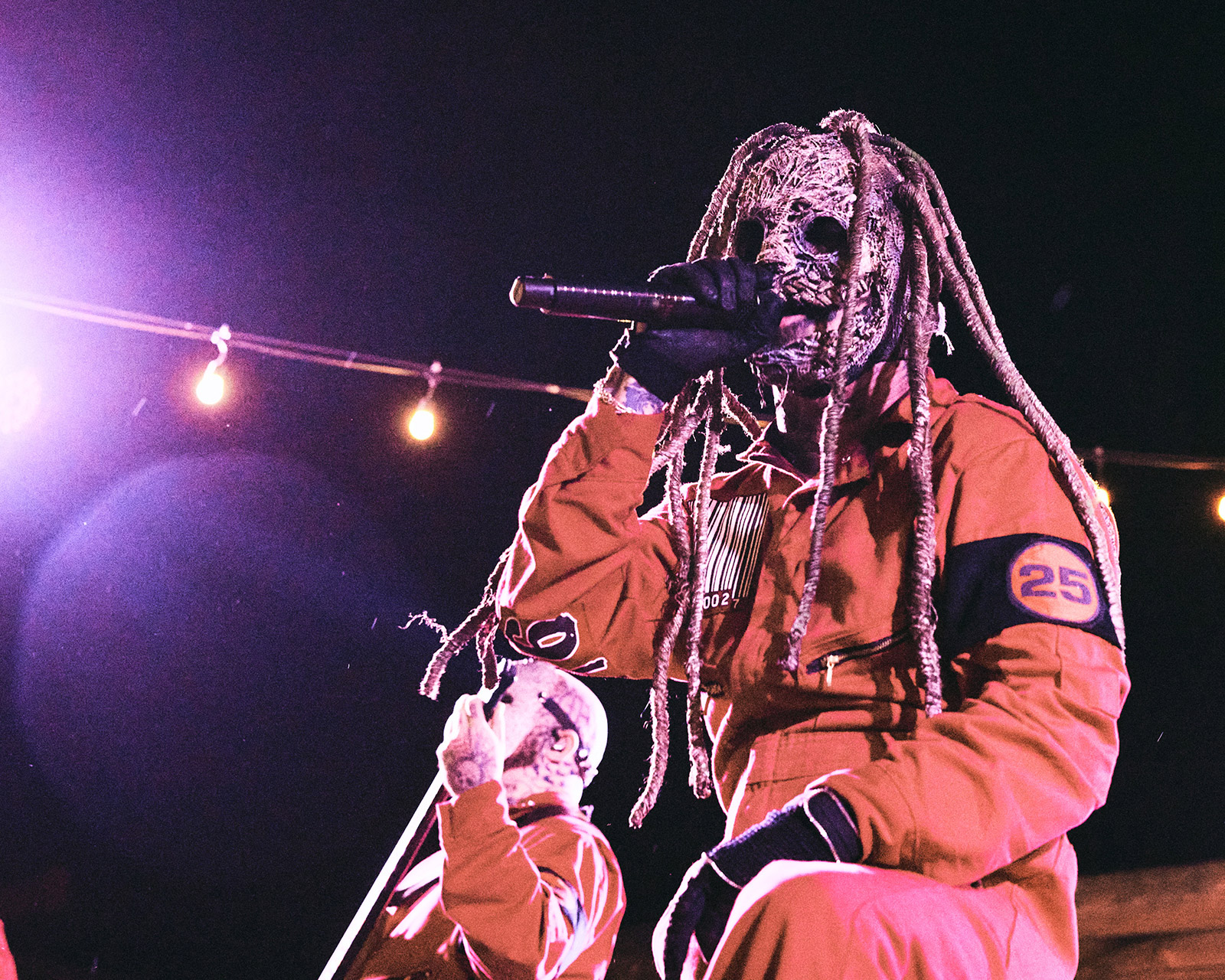

Slayer live in 1986

…

Reign in Blood generated most of the detrimental metal cliches that have hamstrung the genre since. The in-unison staccato palm-muted strumming Slayer employ evokes a relentless, mechanical barbarism, but it also reduces the guitars to percussion instruments and, with almost no bass in the mix, that makes some of the album an exercise in rock-band-as-drumline. It’s interesting, and in 1986 was unprecedented, but it doesn’t make for good songwriting. Unfortunately, that particular audio aesthetic is still being replicated ad-nauseam.

In fact, most of Reign in Blood is still being replicated. Like Neurosis and Meshuggah after them, Slayer immediately spawned a vast army of stylistic imitators, but where those bands inspired subgenres, Reign in Blood probably signaled the beginning of modern metal as we know it. Slayer picked up the torch that Iron Maiden dropped on Somewhere in Time the week before. It’s a critical piece in the history of popular music.

Other bands had expanded the genre in this direction, such as Possessed, Venom and Bathory, but none of their records reached the Billboard Top 200. Reign in Blood was the first popular extreme metal record, and so became the template for many records that came after, many of them bad.

The blurry wall of riffs that epitomizes the middle portion of the record? That’s what most mediocre thrash and death metal sounds like. Imitating their sonic havoc is easy. Writing, placing and performing their stop-on-a-dime hooks is not, especially when most bands don’t have a drummer like Dave Lombardo to sell those moments of space or a producer like Rick Rubin to make sure that when the album ought to be silent for a thirty-second of a second that is truly silent. Metal bands mining for Slayer’s gold just churn up ore.

It’s not fair to crucify Slayer for the failures of their imitators, but it’s also telling that Slayer themselves never duplicated Reign in Blood. Their subsequent albums, South of Heaven and Seasons in the Abyss employ more verse-chorus-verse structures, slower tempos and longer songs. They’re also better records pound-for-pound, even if neither packs a song like “Raining Blood”.

Which isn’t to say that Reign in Blood is bad. But it’s not perfect.

Look back over the lists linked in the third paragraph of this article. Some metalheads hate these lists – especially when they’re made by publications and writers who don’t display deep knowledge of the genre – because they misrepresent the music. They fail to show the world that there’s more to us than Metallica. But we misrepresent ourselves when we remind one another (and new adherents to the genre) over and over again that Reign in Blood is the be-all-end-all. The uncomplicated worship of this record perpetuates its weaknesses, but not its strengths.

Thirty years later, Reign in Blood may be the most influential metal record in the pantheon, but it’s time for its reign to end.

…

…

This article has been edited to more properly reflect the chronology of Rick Rubin’s career as a producer.

…