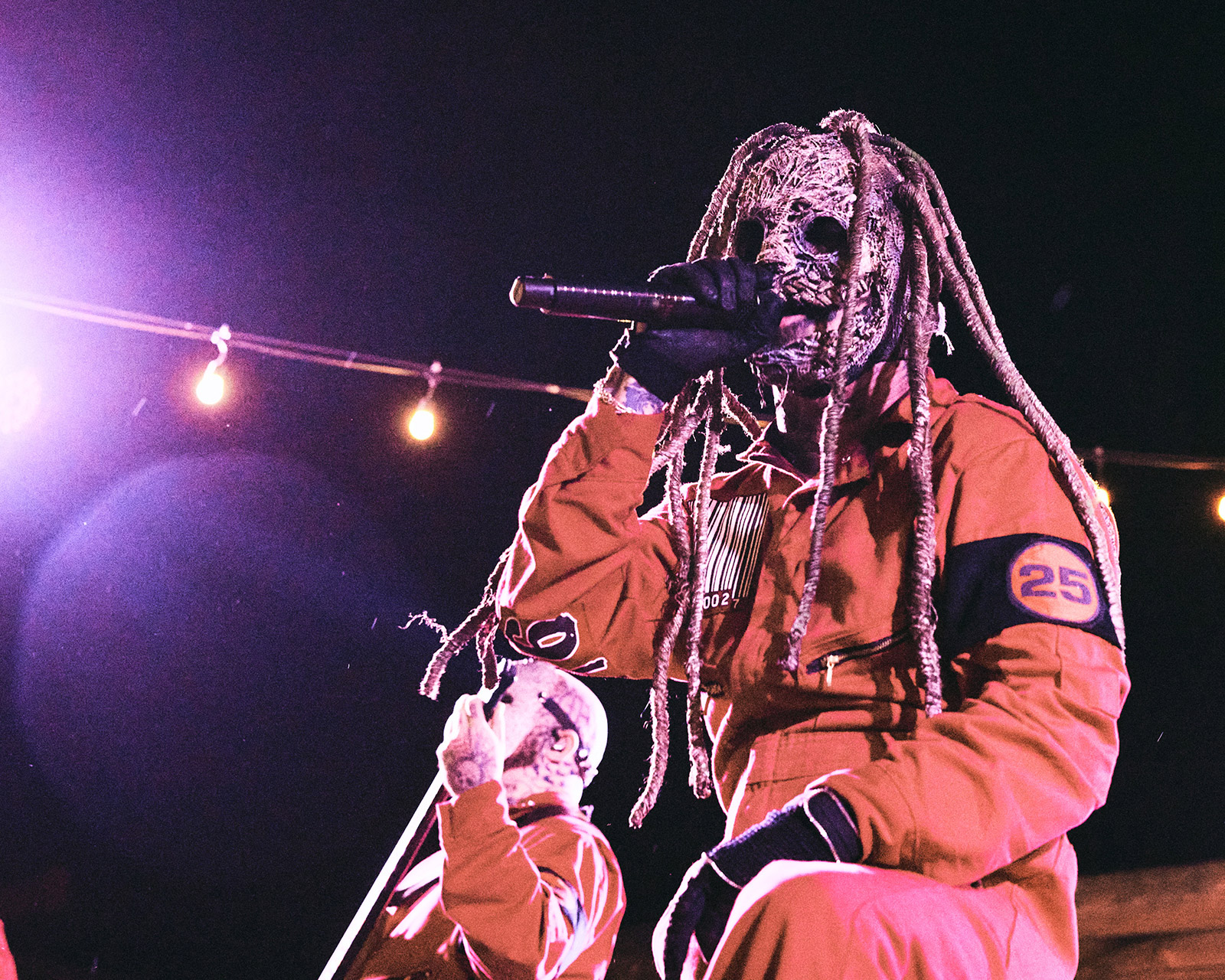

Screaming Bloody Gore #3: Jason Netherton of Misery Index

Photo by Samantha Marble

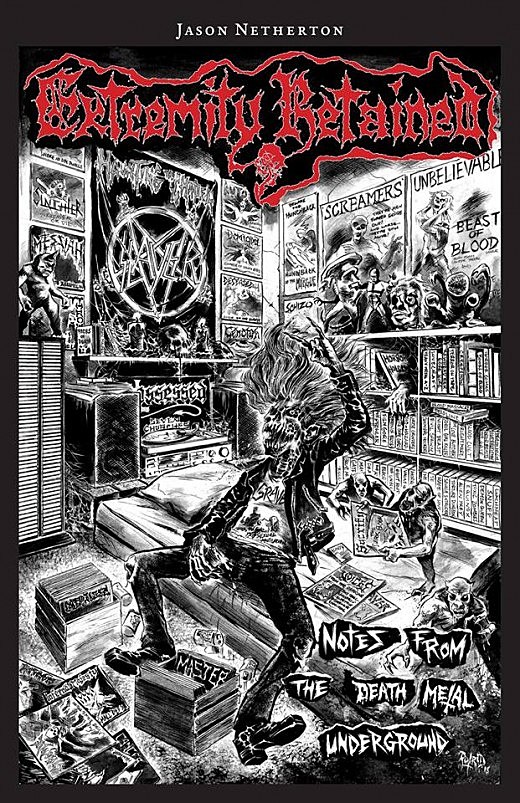

… Metal loves technique. If you want to shred, you must study and practice. Those who would take up the axe or the drumsticks and learn the discipline have plenty of resources to turn to: interviews with musicians, tablature books, explanatory Youtube videos, and so forth. Those who would seize the mic, though, are often left in the dark. This series aims to shed some light on metal’s growlers and screamers. In it, we will sit down with these talented individuals to discuss how — and why — they do what they do. … When you think of classic American death metal frontmen, most of the names that come to mind are probably attached to big, theatrical personalities. Glen Benton. Chris Barnes. Dave Vincent. These men are as well-known for the things they’ve said and done offstage as on; they’re talented grandstanders, but grandstanders nonetheless. Jason Netherton is too reserved — and slightly too young — to be mentioned amongst this company, but he deserves a spot in the pantheon nonetheless. Over the past 20 years, Netherton has quietly become one of death metal’s most reliable musicians. He released a string of seminal albums with the massively influential Dying Fetus during the ’90s, and has since gone on to a long and successful career in Misery Index, who are one of the best and tightest live metal bands I’ve ever seen. Though Netherton doesn’t often call attention to himself, he has a keen observational eye. His perceptiveness has served him well. Not only are his politically-minded lyrics uncommonly astute, but his conversations with other death metal musicians have allowed him to compile Extremity Retained: Notes from the Death Metal Underground, an oral history of the genre that’s on sale now. He also has stamina — Misery Index’s fifth album, The Killing Gods, will come out on May 23 via Season of Mist. They haven’t released a bad album yet. When I spoke to Netherton about the book, his bands, and his approach to metal vocals, his conversational style reflected his music: laconic, efficient, and devoid of bullshit. … … Misery Index have been one of the most active death metal bands in the world since you formed in 2001, but your camp has been relatively quiet for the past few years. What have you been up to? Well, we got done touring on the Heirs to Thievery record in 2011 or so. You know, we’d been doing it for quite a while. Our name was out there; we felt like people know who we are. And we got what we wanted out of it. It was fun to see a lot of different countries and meet a lot of new people, but we wanted to do other things in life too. Our guitarist Mark [Kloeppel] got married and had a son, and he went back to school to do a master’s degree. I decided to go back too, to do a PhD. So it goes — things on our plates. With Adam, our drummer, playing with other bands like Pig Destroyer, we decided to be more of a part-time project rather than full-time. It’s kind of worked out well that way. We enjoy it a lot more because we don’t do it in that it’s-a-job kind of sense. We can use it more as an outlet, which is what music should be. It also allowed us to spend more time on songwriting without any pressure to get an album out by a certain date, although the label wanted it a little bit sooner than we maybe gave it to them. Still, it worked out pretty good, and we’ve never been happier with where we are. What’s your PhD in? I’m still doing it, actually — it takes a while. It’s in media and information studies. I just finished my second year. What does “media and information studies” entail? It’s about the intersection of media, technology, and culture, and how our media helps us interpret our everyday reality, whether it’s the news or whatever. My specific area is the political economy of the music industry and the culture industry: how culture and music are funded, and how it’s worked the way that it has through history. It’s a really diverse, interdisciplinary field, where you can go into information science, you can go into even film theory. At its core, it’s really about how media helps us figure out where we are as a culture, and where we’re going. How big is the existing body of literature on this subject? “Political economy of the music industry” is an interesting turn of phrase. Well, since they started mass-producing cultural artifacts, like records and movies and stuff, people have been writing on this subject. So starting with guys like Benjamin — “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” and all that? Exactly. That’s the core of a lot of media studies theory, and it progressed a lot through the 1960s — a lot of pop and rock criticism looks at the aesthetic side of things, but I’m more interested in how it’s connected to capitalism in general, I guess. That’s clearly been a standing interest of yours for a while. Right. So this is a way that I can get a little more involved in it intellectually. I also just wanted to do something a little different with my time, I guess. It was a present opportunity, so I went for it. This stuff obviously relates to the book you have coming out shortly — Extremity Retained: Notes from the Death Metal Underground. Is writing a book something that you’ve always wanted to do? That sort of came together over the last touring cycle. I was trying to figure out something that I could do with my time — a long term project of some kind. Once you do this touring thing long enough, you get to know a lot of people. You see a lot of the same people in different cities, and you become part of this network of touring musicians. I decided to start documenting the conversations we’d have backstage or in the bus or wherever. We’d often end up talking about the state of the underground, or how it came from where it was in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s to where it is today. Other things would come up too — tour stories, memories from recording sessions. I started to record these conversations, and before I knew it, I had dozens of them. Eventually I worked my way up to over a hundred, over about three years. In my downtime I’d transcribe them and put them into categories, which eventually became five different sections in the book. It kind of unfolded like that. It wasn’t necessarily planned — I didn’t know how it’d end up. I thought it’d be cool to have an oral history of death metal; there have been some other really cool books written about the death metal scene, but there hasn’t been any collection of firsthand stories and anecdotes, like there’s been for some other scenes. I was going to ask you why you settled on the oral history format. Yeah, like — for punk, there’s this book called Please Kill Me. That kind of book, where you can pick it up anywhere and just start reading. I like that. And there’s something about reading from the perspective of the people who had direct relationships with a scene, just riffing on their memories — that’s really interesting. And I really like Decibel’s monthly Hall of Fame feature, which has that vibe too. Even though I often don’t know the band they’re inducting or the album, I still like reading it. The death metal underground is 25 or 30 years old now, so I thought it’d be the right time. A lot of people from that first generation are getting older and starting to drift away. I came into the scene at the tail end of the first wave of the underground — the letter-writing, the tape-trading, all of that stuff that happened before the internet. It was really interesting for me to hear about how death metal became its own distinct subgenre in the late ‘80s from the people who really started it. Was it the vocals? How was it separating itself from the darker side of speed metal? I wasn’t there for that, so it was cool to talk to those guys about that, about how they got their first shows and got the right sounds in the live setting. Will you be selling the book at MDF this year? Yeah, I’ll have a booth there with Dave from Handshake Inc. … … You’re uncommonly well-qualified to compile an oral history of death metal because you’ve been an active musician since the genre’s early years. Things have changed a lot since then — we have Pig Destroyer on TV now. I imagine that your vocal delivery was considered far more transgressive at the time. How did you get started doing death metal vocals? In the words of Alex Webster, there wasn’t any rulebook for death metal back then. Everybody just had to figure it out on their own. You couldn’t go on Youtube and see how people were doing things. It was like a mystery, almost. Even with the drums — you heard people doing these crazy beats, but other drummers would be like, “How are they doing that? What’s the technique?” You wouldn’t know unless you went to the show to see them. As far as the vocals went, it was just like, “Uh, I guess this is what we do.” And then you just start trying to grunt and make these sounds. When I started out, I was really a fan of guys like Karl Willets from Bolt Thrower and Luc Lemay from Gorguts, who had these kinda mid-range, raspy tones. My partner in crime, Jon Gallagher, was more into the deep stuff like Frank Mullen. So he would always concentrate on trying to get deeper and deeper from the chest, whereas I’d just kind of go from the throat. I only sort of remember, since it was so long ago, but my voice came out kinda quiet at first. I just let the microphone do the work. But the more you do it, the more your body and throat adjust to what you’re doing to it, and you become more capable to do more: a little bit louder, a little bit longer, and that sort of thing. How did your non-metal friends and family members react when they found out that you were in a band called Dying Fetus? We were late teenagers then, so to us, it was great. We were influenced by Cannibal Corpse a lot, and we saw how they were pushing the lyrics and the song titles into even more outrageous and shocking areas. We were looking for a name that wasn’t taken yet, first of all, and then something that would have this shock value or ring to it that people would remember. At first we were called Dead Fetus, but then we found out about another Dead Fetus out in the Midwest somewhere, so we changed it to Dying Fetus. Before you could just hop on Metal Archives and check, no less. Hah, yeah, but you had to know. You’d get fanzines and stuff, and you’d look in the back of the fanzine and there’d be some ad, and you’d go “Ugh, okay. Gotta change our name now.” I guess at that age you don’t really care what people think so much, so we didn’t really pay attention to what people thought of it. My family eventually found out the name, and I’m sure they thought it was terrible. But they were cool. Really? They never gave you any heat for it? Yeah, they must’ve, but I think we were pretty clueless about it. We just put the name out there and rolled with it. The underground was still pretty closed at the time, so it was basically just us playing in the garage, and then recording the music and sending it out into the world. It wasn’t like we had a banner displayed with the band name everywhere we went. It was still almost a secret thing. … Opening track from Dying Fetus’s first demo, 1993’s Bathe in Entrails … Though Dying Fetus was preoccupied with gore and other standard death metal subject matter for most of the ’90s, you began writing about politics around the time of Killing On Adrenaline (1998). Do you think that death metal lyrics can be politically efficacious? Are you out to change people’s minds about the world? No, not in that sense. I think that as we got older, I became more aware of the world and started reading more. You eventually get to the point where it’d be cool to start writing lyrics so that when you’re screaming them on stage every night, you’re actually angry about something real instead of some fantasy. It became a way to break out the gore — you’re sort of boxed in with that stuff regarding what you can talk about. So the politics thing was a way to talk about more real-world themes in death metal, rather than just regurgitating the traditional themes. Which are cool too! They’re always fun, but at the time, we were trying to look forward a bit. I don’t think we were even conscious of making a dramatic shift or break. I just thought it’d be a cool direction to go in, because there’s so much horror in the real world. Have you ever felt frustrated while trying to deliver such an involved message through a death growl to a crowd of people who may just be interested in drunken headbanging, rather than the substance of what you’re saying? Well, the music definitely comes first in metal. Maybe in other genres like punk and hardcore, the message is as important as the music, but in death metal, we always put the music first. I always took the approach that if someone wanted to take the extra step and open up the lyric booklet, it’d be there for them, and it’d be their own choice to pursue those themes. We’re also out there to have a good time ourselves. We want people to have a good time at our shows. It was never really a platform to proselytize a political angle. It’s basically an optional thing — if people want to pursue it, it’s there. Have you ever been approached by fans who told you that your lyrics changed their worldview and that they’re now politically active? Yeah, all the time. Ever since the late ‘90s, I’ve had people coming up to me after shows and saying stuff like that. It’s really cool whenever that happens. I think that’s a better way to go about things that trying to ram ideas down people’s throats. I’m just trying to draw out certain situations — social inequalities, injustices, things that are worth being legitimately angry about. Some people who read about that stuff in our lyrics maybe never thought about it before. … You have spent a great deal of time on tour over the course of your career. Do you do anything to maintain your voice on the road? I didn’t used to, but now that I’m older, I do. Jon Gallagher turned me on to this Throat Coat stuff that he uses. I don’t drink as much as I may have used to, since it’s harder to recover the next day. As you get a little older, you become a lot more conscious about trying to perform well, as opposed to just running out there and winging it. You’re more conscious of what your body is doing when you’re screaming at this age. I just try to make sure I’m not pushing things too far, and get my rest and all that. Do you do any warmups or exercises? I usually do a few low screams or growls in different ranges before getting into it for real. In Misery Index, I do only about half of the vocals — Mark and I have been splitting them pretty evenly for about five or six years. We’ll structure the set so that one of us won’t be singing three songs in a row. How long did it take for you to get comfortable playing bass and doing vocals at the same time? When we first started doing it back in ’91 or ’92, we were playing pretty simple stuff. I just kinda started doing both and kept going for it until I got it. Even these days, it can be tough when you have a new song, especially if it’s one you didn’t write — you have someone else’s riff, and you’re trying to figure out where the beats are and how to fit the vocals in properly. The more you do it, the less you think about the lyrics. They just come out. It’s like learning how to juggle or something; you do it so much that one of the tasks you’re doing goes on autopilot. So do you find yourself focusing primarily on the bass while you’re performing, and the vocals are just a muscle memory thing? Yeah. First and foremost, you’re keying in on the drums and locking into them. Then you’re performing on your instrument. The vocals are just sort of over top of all that, just coming out unconsciously. That’s how it is for me anyway. How would you describe the role that vocals play in a death metal band? They’re sort of a type of melody on top of it. They work off the music, like another instrument in a way, but they’re also life of the song, I guess. Not that the instruments don’t have a life of their own, but that’s how I think of it. They serve the same function as they do in any sort of rock song, I guess. Death metal’s not that far from a lot of traditional rock structures, given how they’ve unfolded since the ‘70s. I don’t think it has its own category or anything. You’ve been involved in death metal for your whole adult life at this point, and you’re clearly still heavily invested in it. What keeps this style of music engaging for you? There’s always something novel you can do with it. There’s always a way to push it forward, even if you’re really into the early, primitive forms of death metal. There’s even interesting stuff you can do with that. Even a band like Gorguts — they’re pushing themselves in new directions and they have been for years. Bands now can mix genres up; Portal and a lot of the other Australian bands do that. You can do all of that and still rely on good riffs and good songwriting. Those are death metal’s timeless elements, for me. If you look at the new Carcass album, it’s pretty similar to what they were doing in the early ‘90s, but the riffs are great and it’s got amazing hooks, so it still sounds really good. And if you weren’t there in the early ‘90s, then maybe that stuff is new for you. … …