Progspot #5: Car Bomb, Enigmatic Explosions Evolving Effortlessly, Endlessly (Interview)

…

Like the cutting-edge material which its stalwarts introduced to the world, the character of the East Coast and Northeast mathcore scene around the turn of the century was volatile, sporadic, and ephemeral. As a proving grounds populated by artists with both incredible chops and musicianship, the movement spawned legendary bands like Converge, The Dillinger Escape Plan, and The Number Twelve Looks Like You. The majority of the community, however, stayed confined to more localized underground levels of recognition, and by the end of the 2000s, the scene had all but dissolved into a spectre. But as mathcore began to lose its prevalence, one of its most enduring and defining outfits stepped into the spotlight: performing the discordant, angular riffs and rhythms of mathcore with the grinding speed and hyper-precise organization of progressive metal à la Meshuggah, Long Island quartet Car Bomb emerged in February 2007 with the release of their debut full-length Centralia.

Founded in 2000 by bassist Jon Modell, Car Bomb methodically honed their craft for almost seven years before recording their debut release. Taking an unyieldingly independent approach from the onset, the band tracked and produced Centralia in a homemade studio, with drummer Elliot Hoffman even building his own microphone preamps and compressors. Though the group had signed with Relapse for the release of their first record (the label picked up the band after being impressed by their 2004 demo), it was their only record to be distributed by the label. Since then, Car Bomb has handled nearly all of the outfit’s management independently.

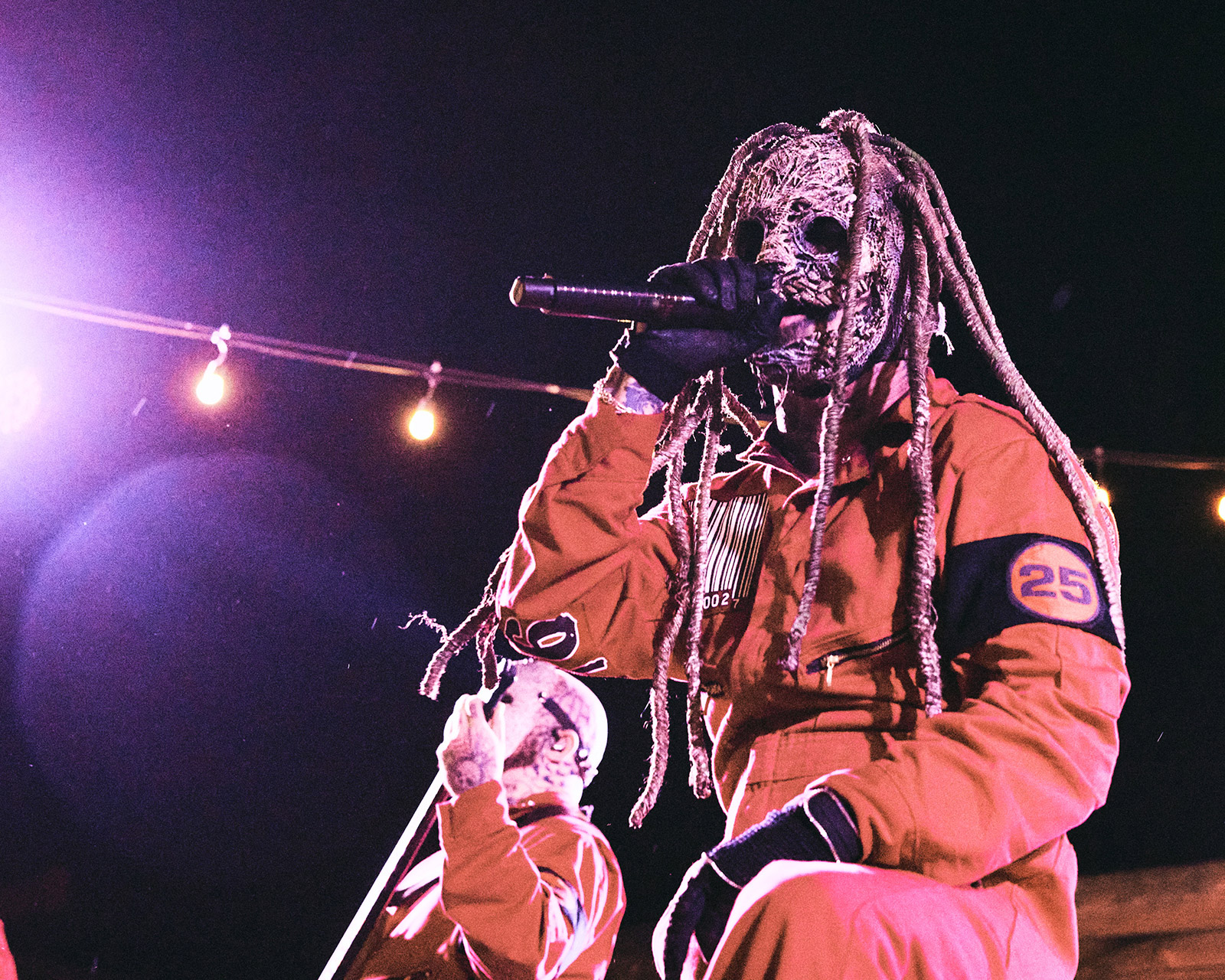

Persisting to the present day with an unchanged lineup consisting of vocalist Michael Dafferner, guitarist Greg Kubacki, bassist Modell, and drummer Hoffman, the unconventional spirit at the core of their sound has survived and evolved along with its members. Though Car Bomb’s true commercial breakout came with the 2016 release of their third album Meta (on which they toured with acts such as Gojira, The Dillinger Escape Plan, and Animals as Leaders), they have been mastering their bizarre craft for well over a decade, a journey that began in 2007 with the mind-bending Centralia.

…

…

A fascinating late entry into the annals of first-wave mathcore, Centralia presented a bedlam of disparate elements: mathcore, deathgrind, experimental metal, and even a sprinkling of free jazz all appeared in its atonality and erratic motions. With this confrontational madness, Car Bomb established themselves as a purely distinct entity even within the avant-garde territory that overlaps all of metal. Perhaps the most pronounced strength of Centralia was in its ability to jar between suffocating guitar attacks and mechanistic bass/drum grooving. Centralia is disorienting and exhaustive, defying any sense of immediate tonal cohesion yet maintaining an overall consistency as a collective work under the Car Bomb brand-to-be.

There’s no doubt that Centralia introduced the maddening, white-knuckled aural rage which Car Bomb would mold over the coming years. With its breakdowns and schizophrenic, Mike Patton-esque vocals alternating between rasping screams and bizarre, filtered mumblings, Centralia juggles double-bass grinding and deathcore-shaming breakdowns with unrelenting fervor, almost joy.

To this day, considering all of Car Bomb’s output, Centralia stands as the band’s rawest and most twisted album, and it was Centralia that laid vital groundwork for all the sounds to come in Car Bomb’s discography.

I had the pleasure of talking to Kubacki in-depth about Car Bomb’s storied legacy — I dug into the relationship between this foundational period of the band and the aesthetic ground on which they tread today, among so much else. This article is a purposefully synchronous testament to the mathematical nature of the band: Car Bomb’s upcoming fourth full-length Mordial (out next Friday) comes three years after their last release, which came four years after their second, which came five years after their first.

I began our conversation by inquiring about Car Bomb’s first era, the release of Centralia, and the stimuli behind their increasingly progressive endeavors.

…

…

Car Bomb was originally formed in 2000; you’ve been going strong since then with no major breaks or hiatuses. You were around for a long time before you even released your debut album Centralia – what was that first era like, and how has your approach to being a band changed since then?

It was weird because I didn’t join until 2002, and then Elliot and Mike didn’t join until a year or two afterwards. So I guess Jon was trying assemble the members first of all, then there was a lot of experimenting and trying to figure out what kind of band we wanted to be. Elliot and Jon on the one side came from Spooge which was a little more technical and progressive, whereas Mike and I were more from the hardcore metal scene, so those two worlds kinda collided and it didn’t really click at first, as far as the material goes. Plus, we all — we still do — worked for a living; we don’t do it as a full-time gig, so we were also starting our careers as well and thus working a little more on our jobs as opposed to the band. It was more of a weekend project. So now, it’s a little more serious: we still have jobs but every day we try to put some kind of effort into the band, whether it’s adding something to the recording, or doing some artwork or something like that.

You mentioned that your influences were split down the middle genre-wise at the inception of Car Bomb. Who were some of your major inspirations closer to the beginning of your career, and which of those inspirations made a profound, lasting impression upon your material?

That’s really easy to answer. It’s pretty obvious in our music, we’re all huge fans of Meshuggah, and we’re all huge fans of Deftones, and Metallica, Aphex Twin, and stuff like that. IDM — which is “Intelligent Dance Music,” it’s kind of a crappy name for people that would be on the Warp label, you know like Squarepusher, Boards of Canada – we were all hugely, heavily into that back in the early 1990s. We grew up on that stuff, so we all had that in common. You can tell especially in the newest stuff really where our influences are. We’re not afraid to just rip off Meshuggah riffs, not verbatim but you can tell “oh that’s the Meshuggah part,” or “oh that’s the Deftones part.” We love those bands so much we’re like yeah, let’s just throw it in. Those are the type of acts that have lasted from the beginning.

Before Car Bomb was a thing, we jammed in a rehearsal space together as two separate bands, and Elliot gave me his copy of Destroy Erase Improve on tape when it came out. I still have it by the way, I have the exact copy [laughs]. As soon as I heard that, and ever since I heard Elliot play, I’ve wanted to keep playing with him forever.

Speaking of forever, Car Bomb’s lineup has remained totally unchanged in the almost 20 years since your inception. Within these ongoing creative relationships, how do you continue to evolve and progress without letting your material becoming stale or repetitive?

That was sort of our intent from the beginning, to always make music that is new to us — maybe just something we haven’t tried before, or something that we feel is unique in the music circle in a certain way. Like I said before, we borrow from a lot of other bands, but we hope to make something that’s kind of us. I think between the way Mike sings, the way I do effects, the way that Elliot plays drums, and the way that Jon has his monstrous bass over everything, I like to think that we have our own thing going on to some extent. But we’re always looking for new things to listen to, always looking for new movies or shows to watch, new artwork to appreciate; looking for new things is just sort of in our DNA, so I think that has a lot to do with it.

…

…

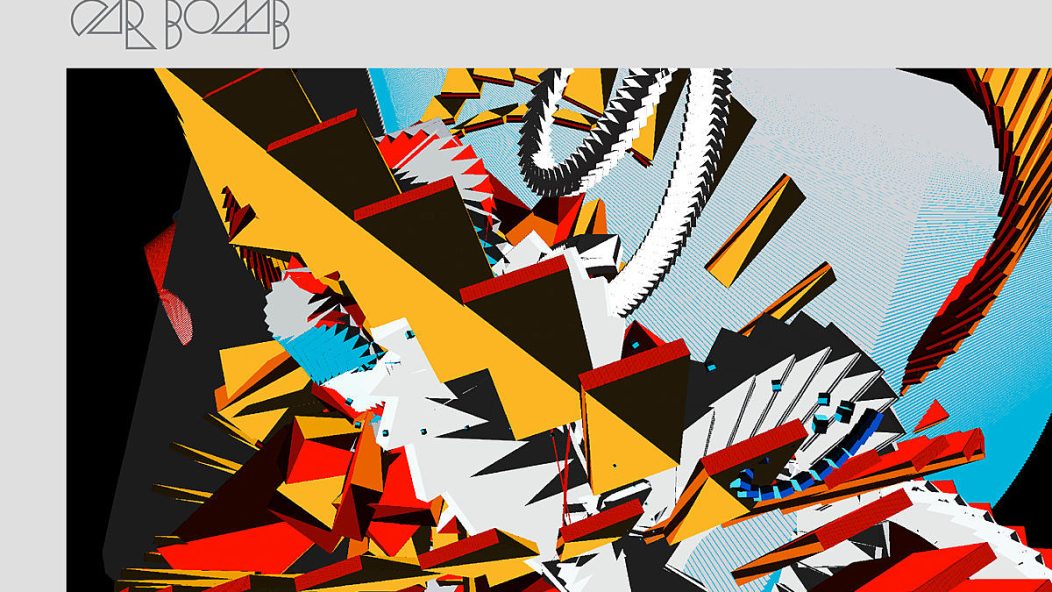

Though Centralia may be Car Bomb’s rawest and bloodiest slab of catharsis, it is by no means their most ferocious. That title is awarded to their second full-length record w^w^^w^w, pronounced as “w click w” but referred to by some as “the waveform album.” Named after the rhythmic pattern of its first track “The Sentinel,” the record streamlines the bipolar hyperactivity of their first effort into a more well-defined frenzy of polyrhythmic, omnidirectional madness. Car Bomb’s list of personal influences came to light more noticeably with this release; with illusory cover art that quite literally looks like it’s squirming around, w^w^^w^w‘s sound is psychedelic in the most nightmarish sense, with moments of electronic noise and uncanny melodicism inserted between Car Bomb’s trademark pummel.

Injecting the fractal rhythmic precision of Meshuggah with an amphetamine-like high, modular synths bubble and swell between riffs in moments of dissonant computerized paranoia. The album’s groovier tracks such as “Lower the Blade” and “Spirit of Poison” both showcased a more cohesive, fully manifest presentation of the group’s seemingly disjointed sound — they sketched out the blueprint for the juxtaposition of dreamy harmony and venomous barbed wire that would slowly become an archetypal recurrence in Car Bomb’s sound.

While Centralia felt more like an outpouring of passion and frustration, w^w^^w^w fully delivered the band’s oddball eccentricities. The unceasing intensity and frenetic impulses that defined Centralia had evolved into something with identifiable self-similitude and direction while sounding even less akin to music written by their peers at the beginning of the decade. In 2012, the once topical mathcore scene from which Car Bomb had emerged had all but dried up, with its more prolific constituents having progressed in various new stylistic directions.

So it was on w^w^^w^w where Car Bomb reinforced and sharpened their intensity, but it was Meta four year later that presented a more refined maturation of their sound. Astoundingly, after 16 years of existence, the band’s material underwent a series of major innovations resulting in a revitalization of their identity. Taking cues from w^w^^w^w’s paradoxical marriage of atmospheric melodicism and chaotic technicality, Meta utilized more clean vocals and unnerving lyrical sections, stretching the abstract tensions of their music even further. Few albus can reasonably claim this, but Meta quite literally abandons all notions of genre — even progressive music, which by definition is limitless — to pursue a sonic amalgam of a newly evolved species of music.

Though still rooted in mathcore, Meta represents a marked shift from the hardcore and punk origins of the genre. Relentlessly chugged riffs were broken up into surprisingly well-organized patterns, and the rapidfire whispers and screams of Centralia were allowed ample space to grow into more thoughtful expressions.

The rift between Car Bomb’s original musical scope and the extraterrestrial realms they now explore grows even wider with Mordial: voyaging deeper into the cerebrality of avant-garde music, Car Bomb’s latest release is a set of biomechanical algorithmic sonic hammers. As an embellished continuation of Meta, Mordial boasts an even greater textural range and a hefty emphasis on its multitude of intersecting influences — with passages of epic grandeur, the record evolves Car Bomb’s signature style with resounding success. Working from a now-proven formula of mad polyrhythmic free jazz destruction, Mordial explores a greater variety of tones while maintaining increased focus on cohesion, yielding a monster wildly eclectic in approach yet monolithic in stature.

Before getting too far with Mordial, though, I first asked Kubacki to explain the process of Car Bomb’s collective shift away from mathcore and aggressive punk to a more experimental prog sound, and if that movement was an intentional one. I also inquired about his thoughts on the steady evolution of their sound, and whether time has allowed for a more thorough exploration of their wildly inventive capabilities.

…

…

Car Bomb’s material can pretty safely be defined as mathcore if you’re to attempt to label it. But mathcore being a more hardcore-based genre, I feel you’ve continually moved away from it, and the progressive metal tendencies have emerged more so in your sound. Do you feel that you’ve intentionally made the move away from punk over time or have you always been more of a metal band?

We always want to have that punk aesthetic, as far as how it feels to play a certain riff. Even if it’s a melodic part, we still want it to have this sort of not-polishedness to it, I guess is the best way to describe it. We try to keep it raw: we don’t try to add too much production or anything like that, we want to keep it pretty rough. I guess on Mordial in particular… in 2017 we toured with Gojira and did 30 days straight. Just to see how they took their energy and pocketed each riff into the perfect part of the song, we were really impressed by that and really tried to strive for that. Instead of making this random, longform piece we tried to go, “okay, we have some random riffs that are in different time signatures, but how can we take more bits and pieces and put them into later parts of the song, or how can we bring a riff and sort of slice it in half or invert it?”

So you’re striving for longer phrases and longer incorporations rather than just a sequence of ideas.

Yeah, and we tried to make each song really different from each other. It’s weird because “Dissect Yourself” is really the only song that sounds like that, that’s the most aggressive, mathy, Dillinger-y type song that we have that’s sort of all over the place. A lot of the other tunes are way more compact. There’s one song that even has this My Bloody Valentine thing going on for a minute — we’re trying a lot of different things on this one. There’s still heavy stuff in there, and there’s definitely one song in particular — the title track of the record — that’s one of the heaviest songs we’ve ever written, but at the same time you can tell it’s not just a long sequence of randomized parts. It’s really trying to make songs that are each their own compositions.

Mordial presents a considerable progression in Car Bomb’s identity as a group, both sonically and aesthetically. In your perspective, what aspects of the record most set it apart from Meta and your other previous works in terms of style and overall approach?

Again, I think I have to go back to that whole Gojira experience, seeing how the crowd reacted to them and how honestly they create their music. We get to see them record and write their stuff since we share a studio together, and everything they do is 100% from the heart even though it’s kinda calculated at the same time. As their music gets more primal, they always track it more like something from Sepultura’s Roots era or the Chaos A.D. era of groove metal. We really don’t do that too much, but that was the real inspiration behind it, like, “how can we take all that we do in our music and make it compact in order to tell a better story? How can we surprise the crowd in spots but also bring it all back full circle?” We’re not really afraid to do that this time around, there are parts that are like “oh that part again!” Whereas with w^w^^w^w it was just like an odd piece of random riff after random riff.

…

…

In terms of translating Car Bomb’s manifold influences (musical and otherwise) into bespoke novelty, Mordial is a wild success. Above all else, it showcases the inexhaustible well of artistic experimentation that is the four-mind matrix behind its compositions — even after 20 years, it feels like Car Bomb are only just beginning to access some kind of untapped potential that hid dormant beneath the surface of their already-incredible material. The album is simultaneously melodious, voracious, intricate, psychedelic, and progressive — to a fault, even — and builds prudently upon elements from its predecessors but repeats nothing outright and makes no compromises in its unpredictability. Mordial is arguably the most “authentically Car Bomb” album, the most singular and faithful to their personally-paved path of musical invention.

As the quartet presents their recursive structures and raw naturalism with surgical precision, they investigate the integration of man and machine, incorporating ideas never before attempted within their music in a sort of cyborgian transfusion.

One of the most well-integrated innovations Mordial lies within its digital instrumentation — the computational tendencies of Car Bomb’s sound have been re-reared via hideously lush electronic elements that go far beyond what the band has done previously. “Start,” the album’s 44-second introductory track, begins the record in a shimmering orchestral landscape more typical of a film score than a metal album. As its layers continue to swell and expand, cloudy chords begin to decay into crackling distortion before the ensuing track “Fade Out” slams the listener with Car Bomb’s signature crunch.

This theme of ambient illustration continues throughout the record with moments of wistful layered digital atmosphere contained in transitionary moments such as the outro of “Xoxoy” or the title track’s minimalist, almost tribal introduction. “Antipatterns” features a more extended example of this aural collage, with a hovering elegance that graces the track with a surprisingly peaceful ending. A more extreme example of the bizarre array of noises utilized on Mordial, the track “Dissect Yourself” begins with Car Bomb’s meaty chug colliding with a confrontational wall of laser noises ripped straight from a science fiction film and ends with unsettling digitally altered vocal samples reminiscent of Aphex Twin.

I wanted to get some more details on the increased use of digital effects within Car Bomb’s music, so I asked Kubacki to explain the technology he uses to create these timbres and sudden noises, and how they had come into an expanded role on Mordial.

…

…

Going back to “Dissect Yourself,” which you mentioned as one of the heavier tracks from the record, I wanted to address the “laser noises” in that song: with the increased use of electronic effects in Car Bomb’s music, what is your approach to blending the organic shape of your riffs and the digital manipulation of such?

Everything is mostly digital now; I use the Fractal AxeFX II and that’s pretty much all I use now because it’s so… it’s like the iPhone of guitar rigs. Especially when you’re touring on the road, it doesn’t make sense to have all these pedals, all these loose cables, and speakers that are really temperamental to the moisture in the air, it makes more sense to have everything inside one box.

So you’ve fully evolved beyond the pedalboard?

There’s one pedal that I still use, I use a Boss DD3 – setting number seven is this cascading pitch shifter, there’s nothing that sounds like that so I tend to use that everywhere, but everything else is the Axe-Fx. A lot of pitch shifting effects, remodulation effects, even the delay and reverb that I do, are mostly pre-any type of gain pedal or amplifications, because that way it sort of makes it part of the instrument.

I think it’s amazing that you essentially have so many pedals that you don’t want to have any pedals.

Exactly, right [laughs]? There’s always another ten pedals you wanna buy. It’s like EuroRack; the thing is, aside from Car Bomb stuff, my friend Rich sucked me into EuroRack. I don’t buy pedals but I buy all these little stupid electronic noise makers thingies and get lost in that stuff.

…

…

The grinding speed and technical mastery of Mordial are as potent as with any Car Bomb record but are now intertwined with layers of symphonic eloquence more typical of a progressive high-concept album. Its constant tempo shifts and brainiac metering splendidly fluidize the whiplash-inducing jolts of previous works, creating a headspace that is much less claustrophobic and self-dismantling even than Meta’s open-ended harmonic motifs could procure. Utilizing dense chords and tonalities hinting at ideas beyond standard brutality, Mordial touches the twisted terror of avant-garde classical composers such as Penderecki or Ligeti in its exasperating density — and, with melodic passages interleaved more centrally than anything drawn from their previous material, Car Bomb tuck lyrical melodic vocal phrases embraced by ethereal chasms of delay between head-spinning brutality, as exemplified through the textural emulsion of “Blackened Battery” and “Antipatterns.” These tracks in particular feel almost like a mutated bastardization of jazz, but in the best way imaginable.

Journeys of the psyche are Mordial’s most profound achievement, and they swell from Car Bomb’s breakdowns with vibrant flourish. “Scattered Sprites” and “Vague Skies” exhibit cascading, interstellar guitar solos which maintain their wicked technicality and asymmetrical contour despite any contrast. Both of these songs in particular demonstrate the album’s central theme of uncanny duality between natural and artificial elements, as Car Bomb’s more spacious harmonic shapes are matched by sinister, digitally manipulated passages. Almost every track on Mordial features at least one passage of clean vocals, often providing bizarre windows of hopeful illuminance to shine briefly upon a composition before dragging it back into the barbed-wire depths of their cavernous sizzle. This increased sense of integration on Mordial sees Car Bomb marrying their more delicate soundscapes with the stark brutality of their music more effectively than ever before: ideas once presented sequentially have now been fused into a singular timbre, and motifs once separate and disjointed now combine in grotesque yet functional chimeras.

Now that the mathcore skeleton of their sound has been refined so thoroughly as to allow for unprecedented expansion into new sonic realms, I talked with Kubacki about the strategies Car Bomb use to achieve these levels of inhuman technicality and precision while simultaneously increasing the naturalist aspects of the record.

…

…

Regarding the complexity and the highly mathematical structure of your material, do you have any special techniques for writing and mastering your music? Do you have a background in music theory?

Not really. None of us are really classically or technically trained. Actually I think the person who had the most lessons is Mike, he was an insane classical guitar player. He was a classical guitar music major at Nassau Community College for three years or something like that. We’re all inspired by modern composers like Philip Glass, Steve Reich, even Stravinsky, stuff like that. Philip Glass is a perfect example, because he always adds one element at a time, he’ll make a bar stretch from 7/8 to 4/4 to 9/8 — and it’s very natural, it’s not this jarring thing. It starts to not sound like a thing that you’re counting, it becomes this textile-like pattern that washes over you, and that’s what we kinda go for as well. If you can count us that’s cool, but if you can’t count us that’s cool too: hopefully you can kinda digest it even if you can’t bob your head to it.

We actually tried to use a little more 4/4 on Mordial. Like “Scattered Sprites,” a lot of that is in 4/4. There’s a couple other tracks that have 4/4 in them as well but we tried to break it up into patterns of five a bit so that the rhythms are symmetrical but the number of repetitions is uneven. We like to do a lot of stuff in 9/8 where we have a section of four 16th notes and then five 16th notes, so it feels like it’s speeding up and slowing down with each shift, it’s sort of an effect that makes it feel like the tempo is changing even though it’s in a different time signature.

You’ve been talking about primal instincts and returning to a more raw expression of your sound; was it this concept that inspired the title of the record? Perhaps its name is a reference to the primordial nature of its sound?

Yeah, it comes from that word. I don’t want to give away too much about exactly what it means, but if you look at primordial and the different terms that can be associated with it, it sort of stems from that. We just like the way that the word sounds: I don’t think there’s a lot of people that use it and we always try to come up with new and unique phrases.

Is Mordial something that could be seen as more accessible overall, or is something that’s truly meant for the fans? What do you want the listener to take away from the record most of all?

I think it’s something more refined as far as we go. We really liked how Meta made an impact on people, and that was something we spent way more time on writing: the riffs, the songs, crafting the sound, getting the right people involved in the production of it like Josh Wilbur. That was a huge part of the experience, as far as being able to rely on other people to make our music better. I think going off that natural progression, we tried to step a little further with this one by bringing in Nolly [Getgood] and Ermin [Hamidovic] for mixing and mastering.

But as far as what people should take away, we just want people to dig it. There are so many records that I keep going back to that I either grew up on or still listen to in my 30s; any Meshuggah record, I can always go back to. Any Radiohead record, I always go back to. Every My Bloody Valentine record, every Aphex Twin release. Like 50% of my listening time is Aphex, I’m embarrassed to say it, that’s all I listen to. In my mind, I hope that some people would like to listen to us as a staple of their catalog, something they can go back to once a year, something that gives them that feeling that I get when I listen to OK Computer or Selected Ambient Works Vol. 2 or so on.

…

…

Mordial represents progression and innovation for a group already more innovative than the vast majority of their peers, stepping into the truly avant-garde by actually aiming to redefine avant-garde altogether. As 21st Century music, Mordial is a major becoming for Car Bomb: their multitude of influences, coming together to transcend time and genre, are all represented with equal consideration, not simply as decoration. Ultimately, Car Bomb represents the blurring line between man and machine, between the authentic and the artificial, between simulacrum and truth.

All music is art, but Mordial is very art. Exemplifying the fractal reality to which their music constantly pays tribute, Car Bomb now comes full circle by assuming the guise of unfiltered spontaneity that surrounded their first record, but this time equipped with an invaluable wealth of experience, self-reflection, and intimidating technological poise. The full range of influences informing Mordial’s sound is readily apparent in the music, and although the record is a strictly musical work, it pays homage to the multimedia spectrum of artwork by which it was inspired.

As one of the most pleasantly surprising (and criminally underrated) bands in a postmodern paradigm, it’s certain Car Bomb will eventually top Mortdial‘s already incredible scope, just as this one now tops Meta. The barest idea behind the band is now absolutely manifest, not as a gory experiment but as a natural expression of the tsunami of tones and textures that backgrounds one of the most fervently unique forces in heavy and forever-uncompromising music.

…

Mordial releases next Friday. Preorder via Bandcamp.

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.

…