Godhead's Lament: 20 Years of Opeth's "Still Life," an Interview with Mikael Åkerfeldt

…

Sometime back around the end of 1998, I was talking to Dan Swanö about how I could improve my situation for writing and demoing songs. At this time, Dan was no longer running his legendary Unisound studio and instead had started to work at a local music store selling gear and occasionally cutting a ”deal”. So, on his recommendation I bought this digital device called Roland VS-840.

It was basically like an old analogue porta-studio, but with built-in digital fx, guitar preamps and eight channels to work with. Unbelievably cutting-edge and mobile in a time between when tape recorders were still used and just before computers had entered any musicians picture by default. I also got a drum-machine called Zoom Rhythmtrak RT234 and some cheap mic for vocals and that gave me a workstation to write and record ideas for songs. Problem was: none of this stuff was user-friendly and the learning curve to scroll around the context of submenus of a primitive interface was a frustrating process of trial and error. In the end I managed to get down a pretty good workflow, so I eventually wrote all the songs and recorded demos for Katatonia’s Tonight’s Decision with this setup.

Mike [Mikael Åkerfeldt] learned about my situation and was eager to try it out. He never owned any recording device up until that point. Actually, the whole My Arms, Your Hearse album was written and arranged in Mike’s head without making any recordings or demos. Opeth actually never released a demo even before they had a record contract. They were signed on a rehearsal tape! Anyways, if you keep all the music only in your head, it’s pretty hard to visualise any extra guitar overdubs and everything playing at once, let alone remembering all the stuff, so he came over to my place a couple of evenings and we started recording bits and pieces to what was to become Still Life. He told me what kind of beats he was after and I programmed the drum machine and tracked two rhythms, leads, cleans, but no vocals, leaving it all instrumental.

So I got to hear a lot of the riffs before they were actually constructed into proper songs and made a personal connection with the material. I loved it! It was quite technical and both aggressive and beautiful. I think Still Life is probably the most underrated Opeth album in their discography, it often tends to get forgotten in the shadow of the other albums. Why? Well, it was their only album on Peaceville to start with. Actually, not long after Katatonia had signed to Peaceville, Hammy, the boss of the label asked me if we’d be upset if they signed our buddies Opeth as well. Our bands had always shared a strong bond since the formative years, so we gave our instant blessings.

Opeth also ended up working with Travis Smith, art wizard extraordinaire, on our recommendation. At this time, both of our bands were still pretty underground and we shared a lot in common ground those days, constantly hanging out and soon even ending up playing a couple of tours together. We did the infamous Milwaukee Metal Fest in the USA and a mini-tour through Poland by train! Yes, the promoter had put us on a fucking train between every gig and they were filled to the brink. People at the stations were behaving like crazy animals and as soon as the train stopped at the platform they jumped in through the windows (!) to make sure they got onboard at all, totally fucking chaos! After adapting the Polish mentality of using sharp elbows, we finally got a ”seat”… in the toilet!!! Standing packed like sardines next to each other with guitar cases, bags and everything for several hours, all dignity gone, Still Life achieved!

— Anders Nyström, Katatonia

…

…

The sigh of Summer upon my return

Fifteen alike since I was here

— “The Moor”

Finding myself so dumbstruck when writing about one of my favorite albums is disheartening. Opeth‘s Still Life came to me at a crux in my life 15 years ago: I was finally honing my own taste in music. I had moved across the country and completely lost the small circle of friends I might have had. I had to switch to a new high school. In short, it sucked, and I was a depressed, angst-filled teenager. The recommendation first came to me by way of an old acquaintance’s AOL Instant Messenger away message:

“Listen to Opeth.”

It seemed simple enough a task — I had recently installed a file-sharing program (one called Ares) and was armed with a particular gumption only found in the gleaming eyes of a sad, bored 14-year-old. “What is this ‘The Moor’ song all about?” Aside from adventures in my dad’s progressive rock record collection, I hadn’t before experienced a song longer than six minutes, let alone one breaking the 11-minute mark (I would later hear their “Black Rose Immortal” and that, aside from extreme ambition or funeral doom, is a song-length rarely matched).

It was enthralling. My ventures into death metal were brief and scattered up to that point, but nothing compared to this. Opeth was something new, but also something old. I might have been naive and young at the time, but I recognized discernable parts in the music. Something might have sounded like that Gentle Giant band my dad liked, and the brutal moments were majestic and interesting. What was once the impassable wall of metal, something I had tried to climb again and again, suddenly seemed inviting. I had a new favorite band.

The facts: Opeth is a progressive metal (mostly) band from Sweden. They were founded as a death metal cover band in the late 1980s but eventually found themselves writing their own material. They have a lot of albums (more than I can think of off the top of my head), but Still Life, the album in question, is their fourth. Opeth plays with dynamics and utilizes lengthy, sprawling progressions in favor of death metal’s traditionally speedy riffage and visceral brutality.

Recorded in the spring months of 1999, Still Life was a turning point in Opeth’s discography. Having then recently signed to legendary metal and punk label Peaceville Records, there was opportunity. Opportunity to make it — to be the biggest metal band in the world. For Opeth, this opportunity was everything they had looked for and worked toward since their earliest incarnation in the late 1980s. Having grown their audience in Europe with their first three albums (Orchid, Morningrise, and My Arms, Your Hearse, all released on Candlelight Records), Peaceville’s distribution — done through Music for Nations, which Opeth would call home from Blackwater Park through Deliverance — would grant them global notoriety.

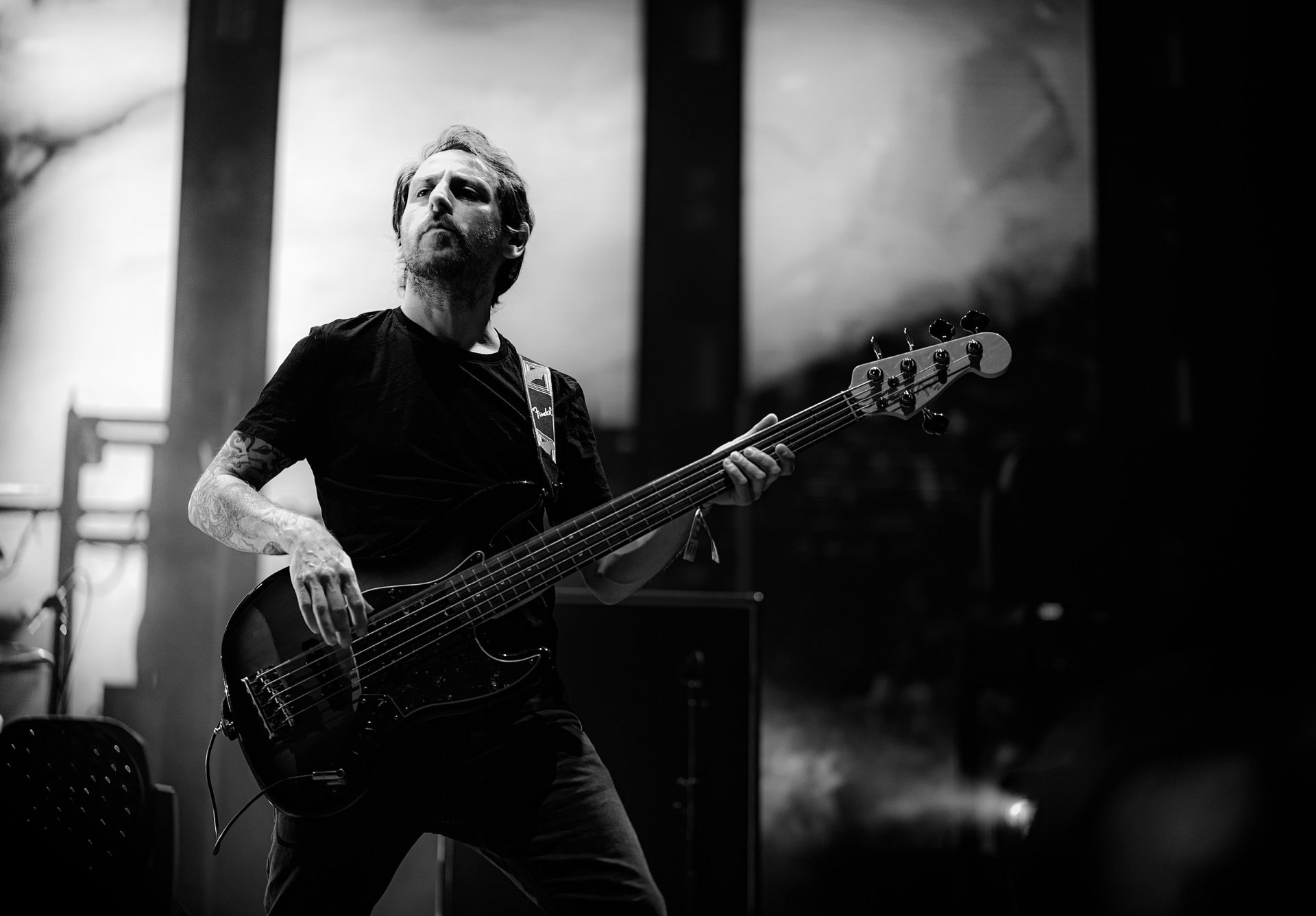

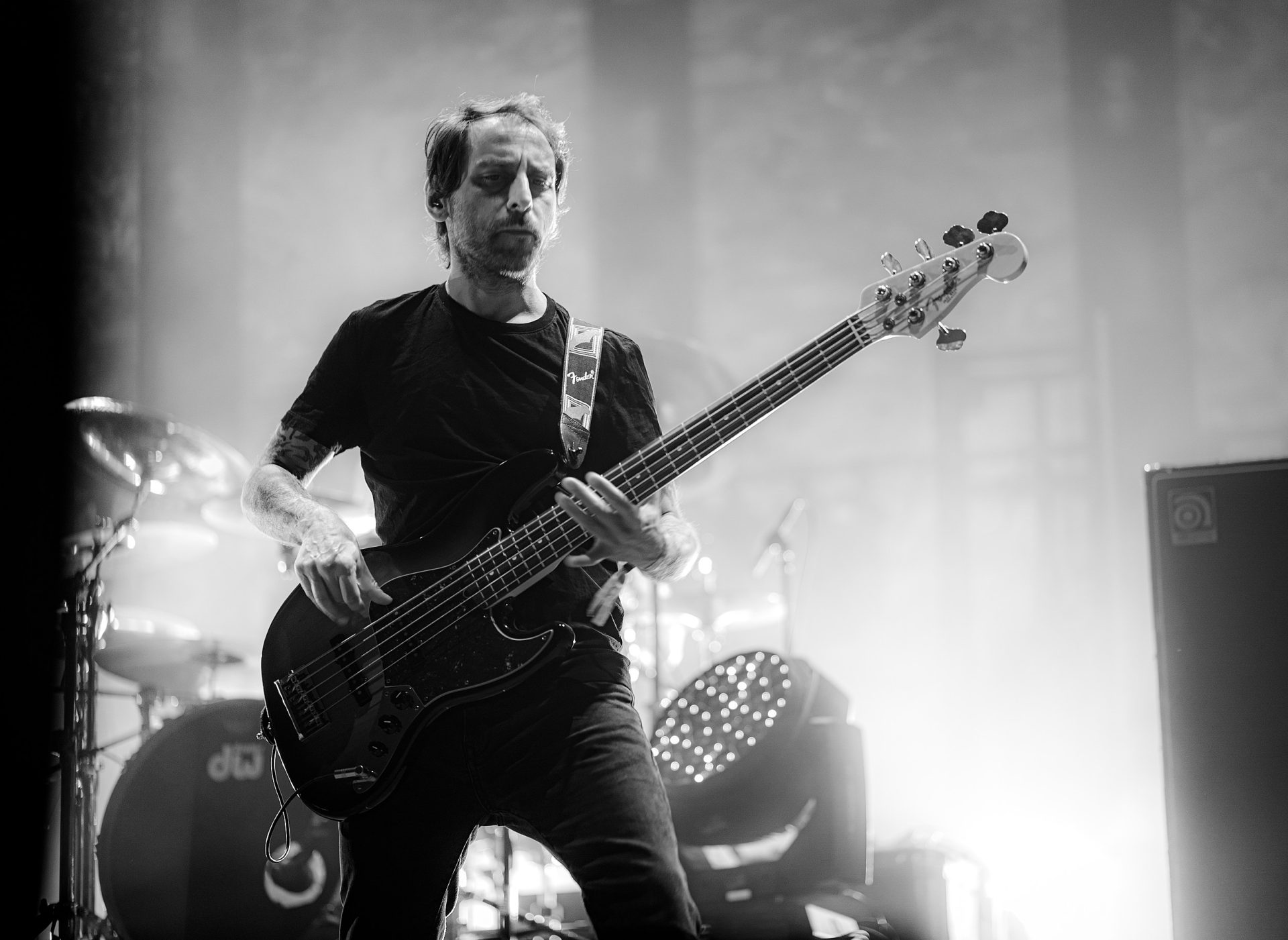

Now officially featuring bassist Martin Mendez, who, as the story goes, joined Opeth too late to participate in the preceding My Arms, Your Hearse sessions and instead slept on the studio bathroom floor, Still Life gave birth to the first instance of the canonical “metal Opeth” lineup, one which would follow them through 2006’s Ghost Reveries. This also gave birth to what a friend affectionately refers to as the “rhythm machine.” Martin Mendez and Martin Lopez were an unstoppable horror of unique Latin rhythms and a heavy presence which helped define what would be known as the “Opeth sound.”

Most people will make the argument that Opeth had finally discovered their sound on My Arms, Your Hearse, and they would be right. That album featured a new sense of cohesive sprawling and a distinctive melodic sensibility which transcended the dual-guitar Medievalisms which preceded. However, it was with Still Life that this new style was perfected and made more sophisticated. Now practiced and filled with the wonder of a new future, Opeth took this chance to, as Åkerfeldt says below, “go all in.”

Though the root of the music is familiarly set upon what came before it, Still Life sees Opeth going for the gold in terms of adornment and atmosphere. With a larger focus on transitioning between disparate sections (a practice which My Arms, Your Hearse did not quite master) and vast, sumptuous harmonies, plus the band’s first documented use of their then-signature EBow (to be later replaced with an actual Mellotron keyboard), Opeth was becoming a fine-tuned progressive death metal machine. More importantly, they were leaving a truly unique mark on the world.

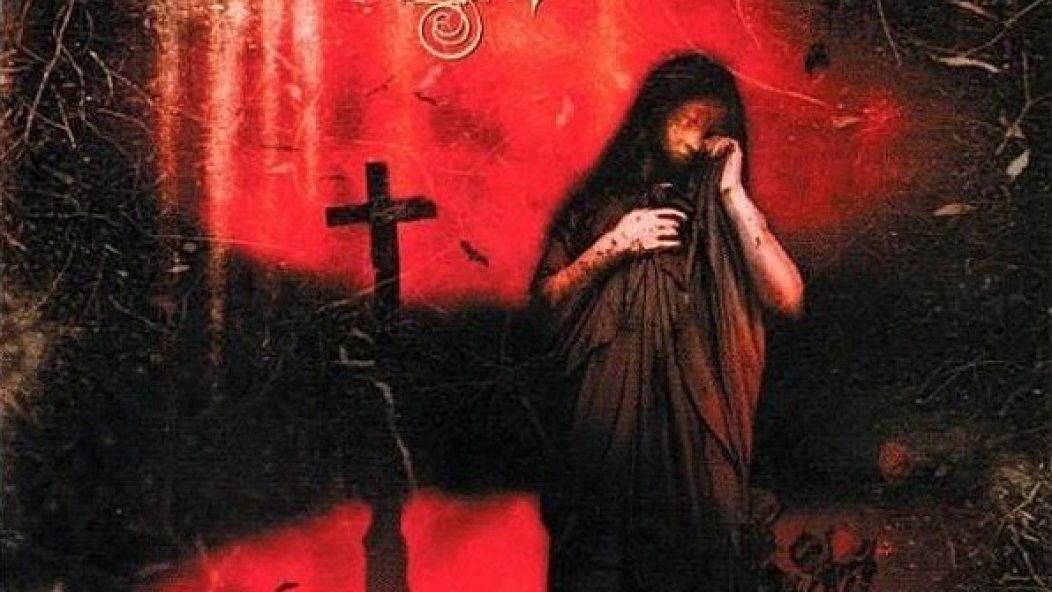

But the world didn’t hear it, at least not for Still Life. Considered a commercial failure at the time, it wasn’t until much later that its gravity fully sunk in. Now considered an audience favorite — and one which frontman Åkerfeldt says the most fans reference in conversations with him — Still Life‘s mark is indelible on the face of metal. With its remarkable cover art, their first outing with artist and graphic designer Travis Smith, and even more extraordinary music, it is hard to believe that this was Opeth’s last fighting chance before considering disbanding. The frustration of not being completely discovered, not touring, and lacking in what the band considered success, Still Life was the band’s last shot, the documentation of a band’s second wind and potential goodbye. Luckily, for us, it was not.

Still Life is a concept album, just like My Arms, Your Hearse before it. Rather than My Arms…‘s ghostly litany, however, Still Life tells a story in vignettes. Cast out from his small village as a young man for his lack of faith, our hero returns as an adult for his true love: Melinda (“The Moor”). He is met with resistance from the village but only wants to make amends (“Godhead’s Lament”). Even so, he is not wanted, and so he beckons Melinda to leave with him (“Benighted”). They escape late at night by lantern’s light (“Moonlapse Vertigo”) and find brief peace (“Face of Melinda”), only to have Melinda snatched away and murdered by the town’s people (“Serenity Painted Death”). Damned once more by his home, our hero is then brought back to the town and hanged (“White Cluster”).

This album, a constant companion of mine for 15 years, turns 20 today. It’s hard to describe what Still Life — or Opeth in general, for that matter — means to me. It’s been half my lifetime, you know? All these memories, all that inspiration, all the progressions I stole and tried from which tried to make something new. Cheers to you, old friend.

I had the chance to talk with Mikael Åkerfeldt at length about this legendary album (and yes, I did shake the whole time), which you can read below. I recommend listening to Still Life while reading it, and if you haven’t heard it before, use this as an opportunity to dive in headfirst. You will not regret it.

…

…

Still Life is officially 20 years old. Does it feel that old to you?

No — I feel like I’m 20 years old, you know? I feel like… I just turned 20, not the album. It feels surreal when someone says that. We usually have an anniversary of some sort every other year, but… Still Life feels like it’s two weeks old [laughs].

Did you expect it to have this mass influence it’s grown over the years?

No, I never… I never had an expectation when it came to any of our records, to be honest. That one, it was the last try before we were going to give up, I think. There was some positivity surrounding that record because we had done three records prior to that one and we had signed to a label which we knew about before we were a band — Peaceville Records. They felt like they were a big label to us. It felt like “wow.” We had a new shot here, but, you know. We had done three records before and nothing had happened for the band. We hadn’t really done many tours. We had done three records and had only done one tour, you know — we toured for the Morningrise record. I didn’t have much hope then, to be honest, so I figured we’d go all in. I was so immersed in the whole prog rock scene and collecting records at the time we did Still Life, so I figured “let’s go all in” and make this record, see what happens. If it doesn’t, then, take off.

I had just moved out from my mom’s basically — living on the couch of a friend — when we did Still Life. I was piss poor, really. Didn’t have a future… whatever future I had looked bleak, let’s say that. At least we got a new record deal and we had a solid band again because Martin Mendez, who didn’t play on the album before, was going to play on this one. Still Life was his first record. It felt like we were a band again and we had a record label, so at least that was something good… but my private life was woeful [laughs].

Did you feel that this personal experience you had… was it reflected on the album?

No, I mean… I had high hopes for my own musicality, I think. I wasn’t uncertain of what I wanted to do musically, it was just that no one else in the whole world seemed to care about us, if you know what I mean. This was in the beginning stage of the Internet, so you couldn’t get a fix… an appreciation, really. It was harder then. I lived in a little flat, second-hand, later on, after that record. It was so slow — I found a flat eventually but I didn’t have a phone, didn’t have Internet. I was so poor… it was poor times. I was happy with everything, but I didn’t have a penny to my name. All I had were these dreams of writing good music.

You had mentioned joining Peaceville — what was the shift from Candlelight to Peaceville like? You had mentioned it was a “shot” for the band.

Candlelight was a small label and they had gotten some success with some black metal releases which were very en vogue back then. They had put out a couple Emperor records, some Enslaved… some records which were very underground, but in the underground were very popular. It wasn’t a professional record label, what can I say? It had some distribution, but we had a shitload of problems with Candlelight Records… just getting everything out. We felt at home with Candlelight and were really good friends with Lee Barrett, who ran the label. But it wasn’t what I thought of when I thought of a record label, it was like a “boy room”-run record label, and Peaceville felt like it was a professional record label. They were also at the time working with Music for Nations Records, and through them they got proper distribution. That was good, we felt like our album would be felt more “seen” at the shops at the time.

Hammy [Paul Halmshaw], who ran Peaceville at the time… he’s a hippie. A weed-smoking hippie. Vegan, same as his wife. They were really friendly and he blew some nice dreams into my head, saying “You’re going to take it all the way to the Royal Albert Hall” or something like that, and “It’s gonna be big, Mikael, believe me,” and I was like “Yeah, that sounds good.” Obviously that didn’t happen, it didn’t happen until the Blackwater Park album. Still Life was… it was a great record, but it was a failure in every other sense.

But it eventually grew. I think of it as a success in the long-run.

In the long-run, yeah… in the long-run. That’s the record I hear about the most from fans that stop me. Whenever we play songs from it live, they go down really well, but at the time it was a failure. It was only afterward that people kind of latched onto this record and found something interesting about it. At the time we didn’t hear anything. We got a few reviews and didn’t really tour for that album. Maybe a few shows — tiny shows — and [people] had very little interest in the band. It was a failure in that sense because the music on there, I thought, deserved to be heard, but it wasn’t.

You brought up that this was your “last effort” before considering ending the band. How did it feel for it to be such, as you called it, a failure in that sense?

Well, I mean, things started happening rapidly for us then, because we put out the Still Life record and signed a contract, so we were obliged under contract to deliver… I don’t know how many records it was, but more than one… and Music for Nations took a liking to us, and they forced us over to Music for Nations after the Still Life record, and they were going to put out what would become the Blackwater Park record. It was turmoil. I was very loyal to Peaceville Records and I said, “No, you can’t do that! We want to stay with Peaceville!”

But at the same time, Music for Nations was a bigger label, a more professional operation. And they had an office! They had an actual office with 20 people or something working in there! And they had put out some of my favorite records in Europe… Metallica records, Mercyful Fate, Anthrax… and they were affiliated with Under One Flag [Records], Dark Angel, and stuff like that. They were bigger, much bigger. But I was very loyal to Hammy and I didn’t want to leave, but in the back of my head I wanted to leave. I mean, I was quite upset when they forced us over. Basically, they played it out like, “If we don’t get Opeth, you’re going to lose our distribution.” That’s what they said — they wanted us that bad. And Hammy called me up in tears saying, “If I don’t let go of you, my business is over, pretty much, so I have to let you go.” At the time, even if it was a bit frustrating and I was sad to leave, I was excited. It was better and safe for us to have that power of Music for Nations behind us. It was all for the better and it breathed new life into my hopes and dreams for this band.

So you could say that Still Life was a failure in one sense, it was opportunity in another.

Definitely, that’s what happened. But you only live surrounding a record, so once a newer record is out, you ask, “What is happening now? Oh, okay, nothing is happening.” And it was a good two years between those two records, and two years with nothing is a long time. It was only until we got picked up by Music for Nations to do Blackwater Park and the record that followed that we actually started to have a career of sorts and started touring and things like that. But with Still Life there was nothing…

Apart from one really good thing I remember from the Still Life cycle… we played our first US show. We played the Milwaukee Metal Fest in 1998? 1999? Whenever it was. We had a packed room. Someone said there were 2,000 people in there and we were like, “What? Two thousand people? It’s like Iron Maiden!” [laughs] We saw that, yeah, there are fans who are listening to this record! We just never told — there was no way for us to get that type of response apart from a few measly comments on whatever tiny little website page we had at the time. But not much happened with Still Life — of course, that was the catalyst to what was going to happen with Blackwater Park and Music for Nations.

I’ve seen that video of the Milwaukee Metalfest show many times.

[laughs] It can’t be good.

Oh it’s great! Are you kidding? I love it!

I wouldn’t enjoy seeing it. That show… there was a lot of chaos surrounding that show. We traveled over as tourists so we were instructed to not say we were playing. We weren’t going to get paid anyway. We didn’t have any instruments. We we were told basically that everything would be there waiting for us when we arrived, and of course nothing was. Katatonia was playing right before us on Stratocasters, which I love today, but at the time didn’t do the trick for us in a live situation. Katatonia were literally walking off the stage, handing their guitars to us, and we walk on with the exact same sound.

Wow.

Yes, it was very, very, very low class. But the people were there, and the support was there, so that was amazing. The fact we made that show happen at all is a miracle, to say the least.

…

…

With this distribution you got through Music for Nations, this was really the first time you got a larger American audience. What was that like for you since your primary audience was in Europe?

That’s the thing you have when you’re a kid — making it in the US. I think that’s the dream for every musician around the world who doesn’t live in the US. To make it there… it’s the biggest sign of approval. You can “catch your breath” for a little while.

We didn’t know that with Still Life. I don’t know who distributed over here, I think it was just imported, but somehow it sold! We got proper distribution in the US for Blackwater Park through a company called Koch that sold wrestling music compilations and Pokémon music compilations and hip-hop and us. It was really weird, and they sold shitloads for some reason. But Still Life, I think it was only imports.

I don’t think I would associate Opeth with wrestling music or Pokémon, per se.

Me neither! I was not happy to be on that roster, to be honest. “How does it feel to be together with some hip-hop gangster rap type thing and wrestling or Pokémon?” I mean, at the time you want to be part of a roster that was strong, if you know what I mean. Metal-strong, not… Pokémon-strong [laughs]. So that was really weird, but what they could do, Koch records, was sell records.

This was the first proper lineup after brief turmoil without a bassist, as you had performed bass on My Arms, Your Hearse yourself, then Martin Mendez joined. What was it like adjusting to his style? Did you find that you had to adjust much?

No — I wrote all the songs and this is something, like… I didn’t have any means to record my musical ideas. I wrote them down on pieces of paper, on a notepad. “Play the Morbid Angel riff four times, acoustic classical midsection, Diary of a Madman-sounding part two times,” et cetera. I wrote that down and had to memorize the songs. We didn’t really have much of a rehearsal space — we had to borrow rehearsal space from other bands to play a little bit. When we arrived in the studio we were very, very unprepared, but the songs were written, pretty much, on pieces of paper. I just had to go through everything with Martin Lopez on when parts would start first on the drums. We went over everything and he recorded the drums and off we went, but it’s incredible, that string of records we did together without rehearsing much or even having songs finished. We just experimented in the studio, and that kind of worked for Still Life. It really worked. We were a strong band.

When it comes to Martin Mendez’s involvement, in those days he didn’t really speak much Swedish or English. Communicating with him was difficult, but he was a very good bass player. He played with his fingers, which was important for us because we didn’t want a bass player who played with a pick. I remember that I played lots of music to him, music that he wouldn’t have heard. Lots of progressive rock. Lots of Stevie Wonder, actually, which he loved the most of everything. We played Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions over and over and over in the studio while we recorded Still Life, which is kind of weird, but if you would ask anyone involved what music we listened to, they would say Stevie Wonder. It’s a big Still Life influence.

That’s great!

Yeah, that was played all the time.

…

As I go into in quite a bit of detail in my book Peaceville Life (Crypt Publications, 2019), I had never intended to sign Opeth. They came as a kind of “side package” when we purposefully went out to sign Katatonia. Jonas [Renske] and Mike [Åkerfeldt] are best friends, so Jonas asked if we wanted to sign Opeth on the same deal as them, as they were out of a label and Music for Nations etc. had turned them down a few times. We agreed, even though I don’t think I’d ever heard the band at that point, well, not really.

When Still Life was delivered, there was no doubting its immense quality. I knew we had something big straight away. The artwork didn’t disappoint either. I didn’t realise how big straight away, but once it was out, the sales took off and never stopped. For me, as I wasn’t involved in the recording, my memories are all of Mike and Jonas coming to stay with us. We did really early internet chat room interviews on IRC and everything was so small scale and fun and friendly. Then again, meeting Mike and his wife in London and it was still pretty low key, but you could sense the band starting to take off big style.

We only ever did that album with them as a label, but what a legacy it left for us! As I look back now, I’m so proud to have been involved in what has become the biggest band we ever had, by far.

— Paul “Hammy” Halmshaw, Peaceville Records Founder

…

We all know about the inspiration behind My Arms, Your Hearse‘s concept as well as what Still Life‘s concept means, but not where it came from. What inspired this anti-Christian concept and social commentary?

I don’t know. I can’t recall, really. It was just some idea I had — I wanted to write a concept album because it made it easy for me to come up with lyrics if I had a storyline. Both My Arms, Your Hearse and Still Life are kind of similar conceptually. It’s a love story of sorts — both of them. My Arms… is a ghost love story and Still Life is, as far as I can remember, based on a main character which is banished from where he lives because he is not religious, basically, and he is torn away from the love of his life. The album starts when he returns to this place to find Melinda — his… his woman, basically. His plans are to kind of make peace with the town and if that doesn’t work then he is going to escape together with the character of Melinda.

Did the concept arise after you were composing the music, or was this something you had in mind when you were making the music?

I had in mind to make a concept record but I didn’t know what it was going to be. So, usually I write the music first and vocal lines I always improvise in the studio, in those days I did, so I didn’t have any idea for the vocals. Not for the screaming or clean vocals, those were all done in the studio. I had the music, and then I wrote the lyrics. Much of it was probably written in the studio, as well, because I was always late with ideas. Music was always first, and then lyrics, and then lots of improvisation in the studio. It was always easy to fit in the screaming vocals. You write a line and you always find a rhythm for them. It was more complicated with the clean vocals, of course, but that kind of worked out. I don’t remember having a single vocal idea before we were actually in the studio, to be honest.

I wouldn’t have guessed that.

No, it sounds like it was really well-written in the sense that it seems really prepared and calculated — everything seems decided, but it really, really wasn’t.

As someone who has essentially memorized this album, it seems like, like you said, it is very well written and everything fits within itself. It is magnificent to hear that this was improvised.

It was a lot of that. We didn’t have a rehearsal space and I didn’t have a portable studio, nothing to record it on. I remember recording some ideas at Anders from Katatonia’s place because he had a 4-track or 6-track on cassette. I went to his place and we played video games and recorded some ideas at his place, but that totaled to no more than ten minutes of music — just riffs — some of which made it onto the record. I don’t know where that cassette is anymore, but there were a few ideas which didn’t make it onto the record which are now forgotten and lost. That’s the only type of music I could listen back to and hear if it’s good enough. Otherwise I wouldn’t know until the record was completed.

With the songwriting, as a listener, I think of the canonical “metal Opeth” style arising in My Arms, Your Hearse, but there is a new brilliance in the antics found on Still Life, like the descending chromatic transition in “The Moor” or as simple the pinch harmonic in “Serenity Painted Death,” as well as the layered harmonies found throughout. It is very dense and shows a new level of sophistication. How did your songwriting process differ this time to include that new density?

I was going so much deeper into my record collection and finding new bands every day. Those days you could still pick up vinyl records fairly cheap. I experimented a lot and picked up records for two or three bucks. “What is that? What is this? Caravan, I’ll see what this is. A Nick Drake compilation? I’ll check that out.” I am a product of my record collection and record collection. I stored those influences. I love music — It’s who I am, basically — and it was the same there. I just wanted to become more and more progressive and, by doing that, distanced myself and ourselves from the metal scene of that time. It was very popular with melodic death metal stuff (and black metal), but not a lot of bands were doing the progressive thing while still maintaining one foot in the extreme metal scene, which we were. That kind of allowed us to shape a sound that was very much ours, if you know what I mean, and that started already on the first album, but I think with what you said with the sophistication of Still Life, I think we reached a new level. I think we were alone in the field to do that in those days.

There was always a separation for the categorization of Opeth. I remember old zines called you “forest metal” because they didn’t know if you were death metal or black metal.

Yes! [laughs]

With this album, I saw more of the categorization of death metal or progressive metal. People were trying to figure it out.

Yeah, there was more of that, but.. we were even experimenting a little bit with jazz music then. I was listening to more guitar jazz like Wes Montgomery, and there was this Swedish band I listened to a lot back then, as well, called Bo Kaspers Orkester, which is very mainstream and people shrug when you mention now them because they are a bit of a household name, but I like them and listened to them. “Face of Melinda” was inspired by my early fascination for jazz music, which is why we have the brushed drums and the kind of weird, “jazzy chords,” or whatever. And I was also heavily into acoustic guitars. I had been working in a guitar shop that only sold acoustic guitars and developed my style in there and became a fairly competent acoustic guitar player which culminated in a way, up til then at least, on Still Life, as there is lots and lots of quote complex acoustic guitar playing on there that I still have problems playing to this day. But I also like to consider myself a better guitarist now than I was then. But it is still quite difficult and quite elaborate, and that came from my interest in Nick Drake — I mean the song “Benighted”… I nicked the vocal line from “Three Hours” by Nick Drake. I listened to so many different types of music, so many different kinds of genres and that is basically why you have the Still Life record. I was also listening to Morbid Angel, which that “Serenity Painted Death” riff was me trying to sound like Morbid Angel.

…

…

Moving from the musical to the visual, this was the first time you worked with Travis Smith.

Yes, he’s done every album since.

What led you to him and what was it like working with him compared to the other art before that?

Well, before it was all self-made. I mean the first record [Orchid] has an orchid on the cover which I ordered, personally, from Holland and got delivered — we had a photographer take pictures. He also took band pictures, but it was still more or less put together by us. For Morningrise we bought the rights to a picture from a picture library, then hired another photographer to put it together. For My Arms…, those photos were taken by Peter [Lindgren], who was in the band then. For Still Life, I wanted to try something new. We signed to Peaceville at the same time Katatonia did — they’re still on Peaceville now, actually — but we signed to them at the same time and they put out the Tonight’s Decision record, which I helped co-produce the vocals for. I was living on Jonas [Renske]’s couch, and he lived on my couch eventually. We were best buddies and still best friends. They came in touch with Travis, who did the cover for Tonight’s Decision. Jonas said “He’s great, you should try him out.” So I reached out to Travis, and the rest is history.

And that really defines the band visually. At this point I think of Travis’s artwork as defining Opeth more than the first three records.

Definitely. Those ideas, I think… I can’t remember, you’d have to ask Travis, actually — I didn’t have many ideas for the visuals of that record. I think he delivered a bunch of pictures and I liked the kind of gothic looking style with the Madonna-like statue on the cover and the house looking thing on the back, and then some kind of — I guess I kind of sent him the concept, so he could kind of make up his own ideas from reading those lyrics, and, especially, I think we took it up an extra notch on the remixed version where there were more visuals which connected to the stories — that was even better. But initially it was all his ideas, those pictures for the sleeve. It became the “Red Record.”

I’m generally not a visual person but I felt that the cover art was just as important to an Opeth record — especially Still Life — as the music.

It is — I always wanted a good, striking cover for the records and that was, up until that point, without any doubt, was the best artwork we had up until then. I still work with Travis, he’s done everything since then pretty much. It was a good choice because it became a companionship of 20 years!

That’s a lasting relationship — you don’t really hear about people finding an artist to work with and sticking with them for so long.

No! But he always delivered, no matter what type of curve balls I threw at him, he always delivered. He’s great and very easy to work with, and by now he knows what I’m talking about. If I send him a sketch that looks like a child did it, he would turn it into a beautiful masterpiece. He is fantastic.

We know stories from My Arms, Your Hearse, like Martin sleeping on the bathroom floor and your horrendous cold, but there is an air of mystery surrounding Still Life — we don’t hear many stories from the studio. Are there any studio stories you would like to share?

I remember we were booked in Studio Fredman in Gothenburg and we were going to record there, but he was rebuilding the studio, redoing it, so he moved us over to another studio called Maestro Music Studios which was basically an old restaurant that had been redone into a recording studio in the 1970s and was home to the progressive rock wave of Sweden in Gothenburg in those days, and it was still running. It was run by a guy called Isaac who was basically a hip-hop producer, I think, but Frederik Nordström did the sound for us and then ditched us, so we recorded everything there on our own on two-inch tape, which was a daunting thing as that is a pretty complex record to just have the two-inch tapes. We had to punch in ourselves, record everything ourselves. We also lived in the studio, I remember, and we also lived in… we rented Isaac’s old flat somewhere, a one-room flat where we all slept on the couch or the floor. It was a very dire living situation when we recorded that record, but we had a blast. We’re easy-going people, just a bunch of rockers from Sweden who didn’t have many things.

One thing I remember is that me and Peter, we were kind of the responsible ones while Martin and Martin were like two monkeys running around. Me and Peter took care of the grocery shopping, so we went out and bought breakfast sandwiches and eggs, cheese, ham, and orange juice, coffee, all those things. There was one day where we didn’t have time as we were working on something on the album, so we had Martin and Martin go out to go buy food and they came back with cigarettes, waffles, ice cream, and ice cream sprinkles, and that was it. And we were like, “What the fuck you idiots, we need food, not candy!” But they liked to smoke some weed at the time, so obviously when you get the munchies you get the sweet shit that me and Peter weren’t interested in.

In the studio… we recorded in the studio, and I might mix it up with a different record, but we started pretty good, around 10:00 p.m. and then however late we wanted to. That was the good thing about that studio, you could work as late as you wanted to. And it was just us, without an engineer, so we recorded it all ourselves. We would work from noon until five in the morning or something like that. So we did everything in that studio, all the instruments were recorded there with the exception of some lead guitars I think, and also all the vocals we did at Studio Fredman, we moved over there at one point.

All the vocals were done in one night. We started at like 9:00 p.m. in the evening and finished at six in the morning, and that included improvising and coming up with all the vocal lines and stuff like that. I was fucked after that. I remember there was some kind of a ping-pong competition on TV, so every break we had we would watch ping-pong because the Swedish ping-pong team was one of the best in the world and it was like the Olympics or something. We would record vocals and then sit down and smoke cigarettes and watch table tennis and go back to recording vocals. It got to a point where we were so tired that I started hallucinating and we saw people in the studio that weren’t there. We heard sounds that weren’t there. So many different things.

The famous “cough” — I’m not sure how famous it is — I remember being in the studio late at night when I was almost hallucinating because I was so tired, and I was gonna record something on whatever song it was — “The Moor” I think — and it was in my left ear, I heard a cough. A person coughing. And I turned to my left and there was no one there. “The fuck is that?” And we got scared. Peter walked around the studio checking if there was a break-in or something, but it turns out it was the old engineer who coughed as we had recorded acoustic guitars and it had bled into the microphone, so it was on the recording. There was no one there. I could probably be able to play it now and tell you where is the cough, but we tried to disguise that, of course, because it affected the recording, so we put some effects on there to disguise it, but it’s still on there.

I’ve always been curious about what it would have been like to have been a fly on the wall there.

You’d probably be shocked, I think so. Shocked at how unprofessional everything was.

I feel like that’s the case for a lot of albums.

Yeah… that was really like that. I was going all-in, nothing holding me back. I had just bought an EBow, so that’s all over the album. I think the EBow was the instrument that had me going into the keyboard world. We used the EBow in the same sense that you would use a keyboard. It’s all over there, playing melodies and crazy, scary vibes. So many EBow and pedals, a phaser pedal is all over that album.

Do you have any final thoughts you wanted to add? Any other memories?

Let me think… I think, I mean, I’m still really happy with this album. I think, with that record, we had arrived, pretty much. There was always something on previous record I wasn’t too happy about, but this was, up until that point, perfect. It’s a bit too reverby for my taste, and I love reverb, but it has too much reverb on the drums. Maybe we kind of redeemed that with the remix, a little bit, but very reverby sounding record. It also has some of our most famous songs that people really like, and we still play songs from there quite often. “Face of Melinda” comes and goes from the setlist. “The Moor” comes and goes. We play “Benighted” often. A long time ago we played “Serenity Painted Death” and “Moonlapse Vertigo.” “Godhead’s Lament” we played not long ago.

“White Cluster” was a song I almost wanted to take off the record because it felt too poppy, I remember. Thinking back now, that feels insane, but I thought it was too mainstream [laughs].

I can’t imagine the album without it.

No! Me neither. That was a new thing for us to do a song like that, but I thought it was too much of a bold move then. I was worried people were going to hate on us for that track. Don’t ask me why [laughs].

…

Still Life released October 18th, 1999 via Peaceville Records. Check out these photos from Opeth’s incredible performance at Psycho Las Vegas 2019:

…

Purchase the Peaceville Story Peaceville Life here.

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.

…