Nasal Death Metal Spelunking With Nostril Caverns

…

It is easy to forget the discipline artists exercise in the creation of their music. There are the hours of practice and songwriting, recording track after track after track for each song, the meditation on concept, the creation of art. These things generally go unnoticed when solely concentrating on and critiquing the finished product, but few fully advertise their process to the world. Such things are secret — rather than demonstrate the flaws and trial-and-error nature of humanity, musicians offer the finished product as a representation of their spirit and testament to their creativity; giving a glimpse behind the scenes puts the image of the musician as a perfect artistic being at risk.

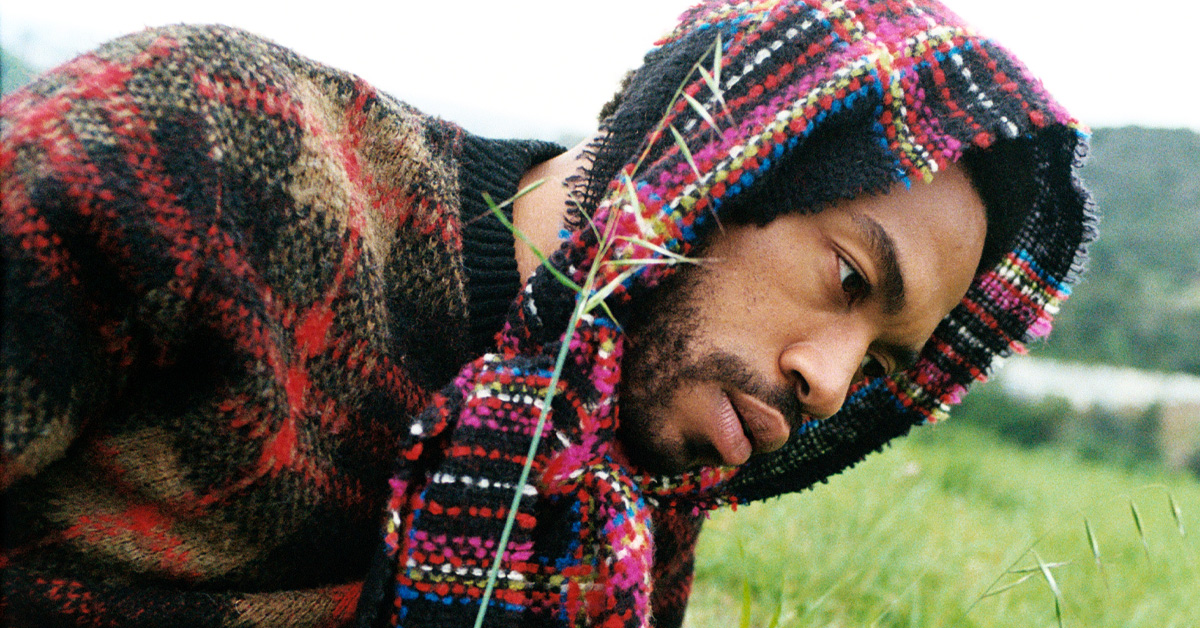

Canadian solo artist Chris Balch, otherwise known as Nostril Caverns, Cora Canning, Time of Death, and so on, throws this caution to the wind. With each new album on his Bandcamp page, Balch includes a litany of goals and stipulations set — songs with 100 non-repeating sections recorded in one take without any overdubs… the maddening list of goals goes on. It is an intense thing to read, and even more intense to hear. Balch’s take on death metal is progressive and intricate, often making dime-turns at a moment’s notice and changing style, and it’s all “just because.” Seeing this disciplined, practiced approach in real time (including practicing and recording videos), Balch’s true transparency is a rare sight in music. As an outsider, it is near-impossible to map Nostril Caverns’s trajectory, but, to Balch, it is a map, and he is the death metal cartographer.

In an interview, which you can read below, we discussed Balch’s transparency, range of influence, and the embrace of absurdity in his lengthy solo career.

…

…

You’ve been making very idiosyncratic music for a long time and under various monikers, so I was wondering if you could introduce yourself and what you do to our audience who might not be familiar with Time of Death/Cora Canning/Nostril Caverns.

Well, Nostril Caverns/Time of Death is my main project where I play all the instruments and do vocals. It started as Time of Death back in 1999 when I was in high school with guitars and programmed drums, plus the occasional vocals and keyboards, and then in 2002 I started playing the drums as well. In 2012 I changed the name to Nostril Caverns, but it’s still the same band. Musically, it’s death metal overall, however there are several other elements that appear on different albums like black metal, tech, math, prog, grind, experimental, free improv, avant-garde, etc. Each album usually has its own theme, depending on what I want to make at the time.

Cora Canning is a two-piece band I’m in with my friend Dave Turnbull. We’ve been playing together since high school and started out improvising and playing covers with Dave on drums and me on guitar. In 2005 I moved away but we still kept in touch and every couple years we’ll get together to record some music and release it as Cora Canning. Musically, it’s all instrumental, mostly improvised, and more rock-oriented overall, but it does have other elements as well like jazz, experimental, extreme metal, prog, etc. We’ve also started sharing the instrument duties, so we both switch between guitar, drums, and keyboards.

Though you’ve been playing guitar and drums for a lengthy amount of time at this point, I understand your roots are autodidactic. Was it your intent from the beginning to pursue this technical, avant garde style?

Not from the very beginning. I was only 12 when I started playing guitar and I was interested in alternative music back then. But my tastes changed as I went through high school and I was drawn to the weird and technical side of extreme metal. By the time I started playing drums, I was already fully into it and writing that sort of music. You can hear on my “Forever Trapped in a Broken Mirror” album when the songs change from programmed drums to real drums, the final

songs with programmed drums are pretty over-the-top tech-death, and the songs with real drums aren’t nearly as technical. At the time, my songwriting had to adapt to my rookie drum skills, but I practiced a lot and am really happy with where I’m at right now in all aspects of my music.

And you mentioned being self-taught, for whatever reason I wasn’t interested in taking lessons and I never bothered to learn scales and theory. I knew what I wanted to make in my head and it was just a matter of trying to create that with my body through trial and error, so I would play riffs on guitar and change the frets until it was exactly how I wanted it to sound. And over time my memorization skills and counting skills have kept getting better.

This idea of “catching up with yourself” seems to follow the evolution of the Nostril Caverns project. Much like learning drums to eventually meet your technical guitar playing, your composing has become more overtly obscure and fragmented, which I imagine is the both source of hours’ worth of practicing and immense discipline. What led you down the ascetic path which resulted in songs which have 100 non-repeating sections, songs which could only be recorded in “single takes,” and so on?

Well I always want to keep trying to improve, so sometimes I’ll do an album where I add an arbitrary rule like “100 non-repeating sections” or “playing drums as fast as I can for 10 minutes” as a new challenge just to push myself. And there’s no denying the huge influence that bands like Thoughtstreams and Normal Love have had on my songwriting, with their changes from catchy riffs to weird note choices to pure anti-music. Stuff that might initially sound unlistenable suddenly becoming coherent after enough listens. These guys are professional musicians who write and read sheet music while they play these crazy songs, and I’m just an uneducated musician but their songs started to make sense to me. Take the song “Hooks” by Normal Love, it sounds like free improv, everyone doing whatever they want without paying attention to anyone else, but the song was actually composed exactly like that and they’re reading sheet music. I can’t read music and play at the same time, so my “100 non-repeating sections” songs were more of an exercise in memorization, and listening to and memorizing songs by those bands over the years really helped.

You definitely advertise and are proud of these arbitrary goals you set for yourself (and dazzlingly achieve) on these albums, but what more do you want listeners to take from your near-obsessive works? That is to say, there are a lot of liner notes concerning the number play and practiced approach, but is there any intended personal effect?

Yeah, I suppose those goals are most interesting to me as a form of personal accomplishment, but they’re really only guidelines for the bigger picture. The ultimate goal of any album is always the same, to make good songs that I’ll enjoy listening to regardless of how they were made. I believe a song can be anything, so no matter how you get to the end — whether you add arbitrary songwriting rules or not — it’s your job to make an interesting song. So the real arbitrary goal of these albums is “how to make interesting songs within the confines of these rules”. Overall I’d say the most common theme for my albums is brutal bleakness, both musically and lyrically. Not to say these albums make me depressed, quite the opposite actually.

Is there a catharsis in that bleakness, or is it something different?

Well it’s just my favourite theme for the music I make. Regardless of a song’s musical mood, if I dig the melody then it just makes me happy, and I dig a lot of “sad” melodies. It’s the same when I write the melodies, if I’m digging it then I’m happy, and if I’m not digging it then I change the melody.

…

…

There is kind of an algorithmic/inhuman character to your Bandcamp page — the amount of data and specificity displayed, the album’s data (title, genre, length, amount of tracks) in place of the artwork [which exists on physical editions], and so on. What makes you treat your music like this in a portrayed way?

For my bandcamp page, I felt it would be more informative and useful for people to see the cold hard data about an album rather than a piece of artwork, considering there are many albums on the page and their themes and genres change from one to the next. But in addition to that, it’s always bothered me in a way how people will be excited over the album artwork without even hearing the music and how the artwork will influence their feelings about an album. I mean, really the artwork has nothing to do with the music, it’s often someone’s artwork slapped onto a piece of music, even if the artist was listening to the music while making the art, are they really connected in any way? So you could say my bandcamp page is a protest against that, emphasized by the ugly Courier font and no band logos. Don’t get me wrong though, I definitely do appreciate artwork and I do enjoy making the album art for my physical releases, but I just don’t let the visual affect my perception of the audial. That attitude projects itself in other areas too, like my live playing. If you enjoy seeing people moving around on stage then you will be completely bored by watching me, but that’s just the way I play and doing something different would be fake.

So it’s like that romantic notion of just letting your art speak for itself with little to distract from the actual content.

Yes, exactly. For me that notion also projects itself in music production. I think no matter how you record your music and how good you try to make the production sound, the music itself will always remain the same, and for me the most important part is the melody. So my standards for not only music production but also playing technique and sloppiness are pretty low — as long as I like the melody then it works for me. As a player I have also focused on being tight and improving, and I’ve also tried improving my recording technique and audio skills, but as a listener those things aren’t necessary for me.

As someone who denies the extra-musical distraction of visual art on your Bandcamp page, why do you think the visual aspect of music has become so important to the modern listener?

I’m not really sure. I mean, I do get it, visuals add a whole extra layer to the music that people can grab onto. And I’m sure there are lots of artists that are making great artwork out there, there’s no doubt about that.

Is it something which does not compute in the microcosm of your music creations?

Yeah pretty much, it’s something I must have started to fully realize back in my 20s and at this point it’s not really something I think about at all anymore. Musically, I sort of exist within my own little world and work on creating things I find interesting from three points of view I feel are necessary — as a listener, as a composer, and as a player.

I’ve noticed you are particularly generous when it comes to physical media, often selling CDs and DVDs at a loss (if you even charge anything at all), generally with free shipping to most parts of the globe. What made you choose this kind of approach?

Physical releases are something that I’m really happy to offer because it used to be tricky to keep costs down for an independent DIY musician who only sells a few copies of an album at most. But, these days you can get good quality CDs individually made for very cheap. I use Kunaki for CD manufacturing and shipping — you upload your music/artwork and they’ll make a CD and ship to many different countries for just under $6 total for one CD (that includes shipping). This is perfect for me because I can just order a CD whenever someone buys one from my bandcamp page and it’ll get made and ship directly to the buyer. I’ve also cut costs by recording at home and mixing myself, and I’m the only band member. So, considering the modest amount of orders I do get, I don’t mind making/losing a couple dozen cents per order, depending on the Canadian exchange rate. I personally still listen to CDs often, so I’m happy to offer really affordable CDs for anyone else out there. Low prices are always nice, right?

Looking back to your personal music evolution, what initially drew you to technical and/or brutal music?

I wasn’t that interested in music in general until after my family moved us to a new city when I was 12. My friend from the previous city came to visit and gave me the White Zombie Astro Creep album on cassette and I remember listening to it and thinking it was basically just noise — I just couldn’t comprehend it. But, after a few listens, I started to “get it” and, after we moved to another new city when I was 14, I went back to the previous city to visit and a school mate sold me his Tomb of the Mutilated album by Cannibal Corpse. I had heard of them from this guy on my hockey team and apparently they were super heavy, so I bought it and I remember listening to that cassette the whole way home. So I’d say that album is responsible for getting me into brutal music. I think the technical side was always partly a

natural evolution as I improved as a player and listener. As you realize how songs are made up of different riffs that repeat multiple times throughout the song, you start thinking of ways to try to do things differently from how you’re used to doing them, to keep things interesting. I remember shortly after I recorded my first album back in 2001, I was so annoyed with how the songs were arranged fairly traditionally, and in 2002 and 2003 I really started to focus on getting away from that. Also, I played a lot of competitive sports while growing up and I honestly think that’s partly responsible for what I’m doing musically today.

Considering the more abstract composition and technical directions in which the Nostril Caverns project is moving, do you feel there is any sort of singularity or limit to what you can or will be able to do? Or is that more of a challenge you’re willing to attack?

I think there’s definitely a limit for some things, for example I’ve had to adjust how I play guitar because I’ve been getting pain for a few years in the index finger on my fretting hand when it’s in a certain position, so I’m more careful now and avoid that position. I’m also 35 now, which I suppose isn’t that old, but I don’t see myself getting that much faster over the years. But compositionally I still feel like there’s a lot more to explore and experiment with, the possibilities really are endless. That “100 non-repeating sections per song” album [Satan’s Unnecessary Elaborations] was a big step for me where I was able to show myself that I could write and play really elaborate and complex songs. It’s funny, after I finished recording those songs, I went on to record the rest of that album that had less elaborate song structures and I was shocked by how easy it was to finish those songs compared to the 100-sections songs. So I’ll just keep setting the bar a bit higher for myself and see where it takes me.

Now that you’ve achieved what most would think impossible with the “100-non-repeating-sections per song album,” what is the next big hurdle for Nostril Caverns?

I’m currently working on an album that will have 1000 short songs, but it’s all improvised so it’s just a matter of getting everything recorded and mixed, which will take time. I think the next big hurdle would be the “1000 sections album” that I will hopefully start writing some time this year. It will be one long song that has 1000 sections, but this time sections will be allowed to repeat, so hopefully it won’t be too much of a pain to memorize. And if that goes well, then maybe I can try 1000 non-repeating sections, but it’s too early to tell.

…