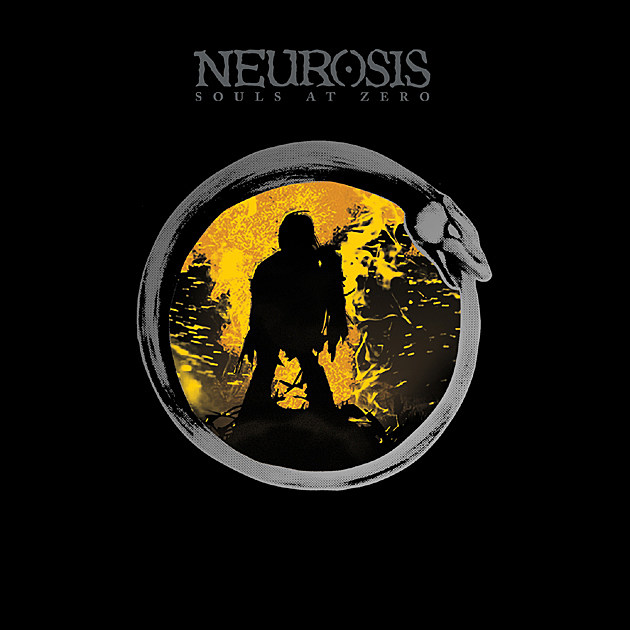

Neurosis' Souls at Zero: A Retrospective

Souls at Zero was the album where Neurosis changed from Bay Area punks into the band that would shape the direction of metal for the next two decades. It’s rougher than the following album Enemy of the Sun and very much the work of a band finding a voice, but nonetheless an urgent listen that hasn’t aged. Souls is a wildly emotional ride packed with keyboards, hypnotic riffs, samples, and plaintive vocals. No song grabs me like “To Crawl Under One’s Skin”, which begins with clanging bells, follows with keyboards, and ascends to a simple, overpowering riff. The band’s label Neurot recently reissued Souls with new packaging designed by Josh Graham, who handles the band’s visuals. Co-vocalist and guitarist Steve Von Till shared memories from the making of a classic.

. . .

Where was Neurosis when you were writing and recording Souls at Zero?

We were part of a fringe music scene and on the fringe of mainstream society. We were in the Bay Area, so it wasn’t that strange. We’d toured the country and had our eyes opened quite a bit. We’d seen what life was like in the Midwest and South and East Coast.

There was no financial infrastructure for a scene like ours. Things weren’t happening in clubs; they were happening in living rooms in basements. I was pretty sure my purpose on Earth was to be with these guys making this music. Souls was about pushing the limits and stretching the lines. There was a lot of growth psychically and psychologically. None of us wanted to give up or cop out or take the easy road.

Souls at Zero came out in 1992. When did you start working on the material?

That’s a long time ago (laughs). I assume it was probably about 1991. I know we demoed some songs first. We toured with the The Word as Law quite a bit, but we realized that some of the sounds we wanted couldn’t be produced by a guitar. We needed to bring in new elements.

We started to pay attention to what Coil and Throbbing Gristle were doing. There was a whole sound palate outside of traditional instruments. We heard about people using samplers and wondered if we could do it. If you wanted to make your music sound like a train crash, you could get a sampler and make the train crash. Why not have sounds of the environment and beasts and nature all be part of your palate? There wasn’t anyone playing like that. We found a guy who was into goth and had a synthesizer and sampler and we dove in. We tried every cliché in the book.

Was that Simon McIlroy? Can you tell me about his contribution?

It was an interesting time of adventure. We ultimately ended up not having the same musical path. There was some musical crossover like Joy Division. He didn’t have any experience with heavy music or big guitars. But we explored new territory together.

. . .

“To Crawl Under One’s Skin”

. . .

Did Souls at Zero change Neurosis from a band that just recorded songs into a band that offered an immersive experience for listeners?

Absolutely. It’s when we started using visual projections and borrowing ideas from psychology about using archetypes, throwing them so rapidly at people that you break them down. We wanted to use the technique to being the audience where we were. We became the medium for the music. We borrowed a little bit from 1960s psychedelia. We raided all this (film) footage from the past 40 years because we didn’t know how to do it. Pain of Mind and The Word as Law were steps, but Souls is where we pushed the doors wide open.

Still, it was a baby step because we hadn’t learned the biggest lesson. The biggest lesson came on tour when we realized we were too caught up in our heads and too technical. We needed to have out-of-body musical experiences, [to] almost make trance music. But we didn’t need to create it cerebrally. If we surrendered, it would flow. That’s the lesson we learned touring the material.

How did you find the guest musicians who played on Souls?

We asked around. The woman who played flute we knew from high school; she was in the band. The violin player — I’m not sure how that connection came. It just kind of worked out. It was our first time playing with additional instruments, and it was a learning experience. We weren’t composers. We didn’t know how to come up with a cello part. What we learned is you find someone tuned in and let them do what they do. It wasn’t very structured, and it was sometimes immature. But we wouldn’t be where we are without it.

Did the musicians walk in blind or did they know it was heavier music?

We took demo versions of rough tracks and worked with them before they got to the studio. We didn’t want to waste time because we didn’t have any money.

The band has had a rift with Jello Biafra, but he is credited as the “mix doctor”. Do you remember his contributions?

He sat there and gave his opinions while we mixed with the engineer. We had a mix we didn’t like. It was our third record and only our third time in the studio. We thought something wasn’t right, and we need to get it figured out. Who do we know who has a lot of experience mixing records? For better or worse, we thought of Biafra because the relationship was good at the time. He’d mixed a lot of records and had a lot of opinions, so we thought we’d tell him what we don’t like about it and see if he could provide another objective set of ideas.

Was his feedback valuable?

Probably. That’s the mix that we stuck with. That was us mixing it with him and Bill [Thompson] the engineer.

. . .

The Wicker Man (trailer)

. . .

The reissue includes new artwork. What’s new and different?

The bonus tracks are the same as the first reissue. We kept the audio the same. It’s basically a total repackage and redesign. There were things we didn’t like from the original. The new CD comes in a consistent color scheme, our key colors of black and silver. We want there to be continuity if you have our catalog on the shelf. We want things to look like they belong next to each other.

Also, those records were done in the early ’90s, and Souls was done before people even had personal computers. We had a guy do some of the layout on the computer. Enemy of the Sun was the first one done entirely on computer, with these huge discs that held nothing close to what you could put on a flash drive now.

Josh Graham, our visual artist, is top-notch. CDs are so small, and it’s tough to think of something epic. But this gave us a chance to set him loose. We had him stick with the iconic imagery and present it like he wanted. It’s a vastly improved visual presentation.

Where did you come up with using a totem on the cover like the one in the original film version of The Wicker Man (1973)?

I was obsessed with the movie. It seemed in line with my spiritual views and with the trancelike nature of the music and where we were going with honoring things from a time long gone. We wanted to use a still from the movie, but we couldn’t without paying a few thousand dollars. So we got together a bunch of guys and built our own Wicker Man and took it out to the beach at Santa Cruz and burned it. We had a bunch of friends with cameras. Right before the damn thing fell over we got the picture we needed.

. . .

BUY SOULS AT ZERO (REISSUE)

. . .