My Autism: Imagine a Hose Hissing Hot Color Pressed to Your Face

…

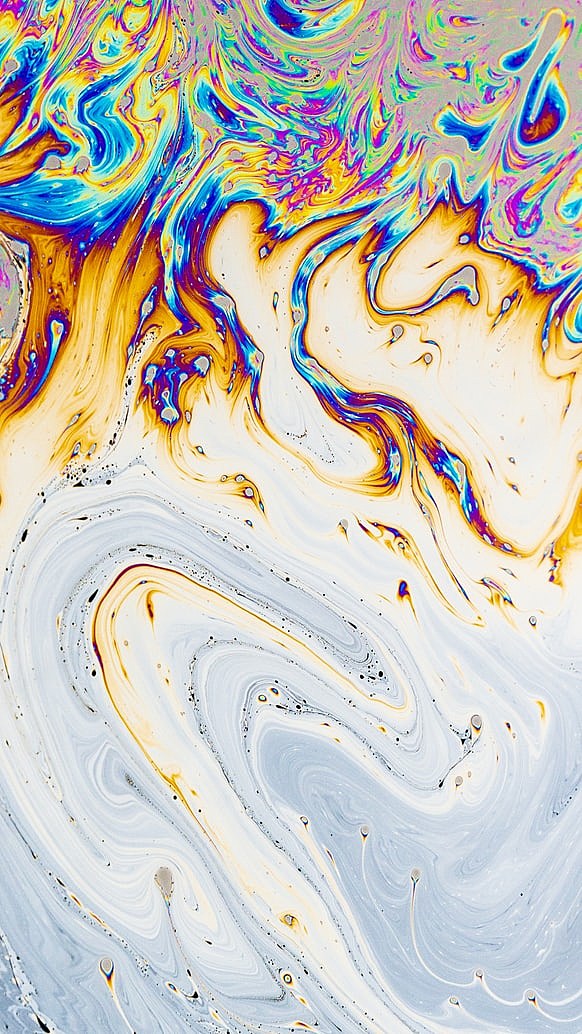

Imagine a hose hissing hot color pressed to your face.

My name is Langdon Hickman, and I am on the autism spectrum. My diagnosis came late in life. This provides certain problems. Our understanding of autism has deepened over the years but its origins are problematic, to say the least, and the first serious inroads to understanding it outside of deeply ableist terms came with observation and treatment of children. As such, tests for adults are inaccurate in various ways, capable of telling the truth but in such a scattered way that they are hard to go by. The solution, then, is to take lots of kinds of tests, some behavioral and some therapeutic (as in administered via a therapy session), and some assembling notes about your life history. It is messy and imperfect and, in truth, often more validated by responses to treatment we know work for people on the spectrum rather than purely a diagnostic capability, the equivalent of deploying a series of specialized drugs and noting which one made you better and determining from that what the disease must have been. Despite these blockages, it is still possible to make diagnoses. All medicine is organic in practice, a continuous observed and adjusted process rather than a static set of declarations, and mental health and neurodivergence are no different, so this softer and more involved diagnostic practice is less troublesome, if still imperfect, than it may sound.

All that said, the tests I went through came back positive pretty quickly. There were always little signs, as there typically are with these kinds of things. I’m booksmart, sure, in that traditional way with complex and mixed usefulness, and I’d had the tell-tale issues arising from that, where I would hurl myself headlong into the seething maelstrom of raw data, like a whirlwind of ice and glass and sand tearing at my skin until, by standing still, by weathering the storm, I would accrete motes of learned data in clusters until it eventually formed an armor I could use to navigate that abstract world of intellect and information. I had experienced the perverse social stigmas of this as well as the malformed and infantile responses to that stigma, becoming resentful and condescending to my peers to compensate for the mysterious and painful sense of alienation I felt. I told my therapist the same kinds of things that people on the spectrum relay to their therapists regardless of age: that I liked being booksmart, sure, but I wanted more to be normal, to not say the wrong things at the wrong time despite the best intent so very fucking often, to have normal relationships where I understood what people meant without beleaguring them with 20 questions. The testing process was quick and the assemblage of previous therapy notes was quick. There wasn’t much doubt at all.

I will say a lot of things and my brain will fire arrows in many directions. Navigating my thoughts is often more like walking a maze blindfolded, hands pressed to the wet stone of the walls, feeling the temperature and texture of the rock change and forming a secondary sensory map of tactile information in replacement of what for others would be the primary mapping sense.

Another way to think of them is like having your skin peeled so you are all bright iron-red muscle wet with blood, raw nerve exposed to open air, placed inside a thick rubber suit with a great big fishbowl helmet and oversized and hardly mobile black gloves, thrust into a heaving womb of smoke and fog, and it is in this new world that you must navigate the life and world of others.

You know your own senses, can feel every inch of your raw body on fire within its containing suit, but the suit is too thick and it muffles and mangles your words and so outwardly you seem almost unfeeling, bumbling, catastrophically inept. So you develop new strategies, ways to navigate and make sense of things in secondary fashions, deducing through abstract methodologies what to others is clear and obvious. You say the wrong things in social situations and people think you are a weirdo, but you can act normal enough that they think you’re just an ass rather than blaming it on miscommunication, and there is no way to correct them after the fact. You can see the effects of your words and actions but you can’t immediately process how they connect to each other and all your first guesses are wrong, and your second too, and you pray that someone will happen along and give you some kind of hint before you burn every bridge in your life without even understanding what’s happening. It is a lot like being caught in a burning house with someone blocking the door.

Imagine a hose hissing hot color pressed to your face.

The previous scenarios make life on the spectrum sound apocalyptic. Unfortunately, this can sometimes be the case; the feelings of humiliation, like people want you not only to feel sorry but humiliated, stupid, worthless for the mistakes you half-beg them to help you with, is acute, and it is hard not to carry a stone of calcified bitterness inside of you. People are cruel and often take out the hurt they have experienced on others in their lives, a trait I cannot say I am totally above even though we all wish we were. But this sense of terror and humiliation and shame comes, thankfully, painfully, thankfully, only out there, in the wilds of the social world, which to an autistic mind feels at times like wandering naked and smeared with rich sauces through a valley of wolves, a thought which takes an amount of deliberate therapy to disarm and untrain.

It is here that I confide the potentially embarrassing fact that one of my favorite stories is The Secret Garden. Its plot, in brief, is not atypical of British children’s literature from the early 20th Century, dealing at first with an otherwise unmarked setting of British imperial control of India. It is there that the main character, a young girl, is raised by neglectful parents who never wanted her and thus never try to be real parents to her. She is raised by servants who have no experience with children, resulting in a child that grows into a bitter, nasty, and self-centered brat more out of isolation and desperation than any real sense of malice. After cholera comes and kills her parents and servants, she survives there alone until she is at last discovered amongst the dead and sent to the manor of her family. It is there that she learns of a special place, a beautiful and rich rose garden, its door hidden within the manner and the key doubly-hidden after the death of the lady of the manor in the garden. Eventually, the main character discovers a hidden bedroom with her bed-bound and infirm secret cousin, their malicious ableist shame toward him leading them to lock him away, as well as a young and similarly abandoned boy of the area. Together, they eventually find the key to the garden and, on spending time there in the peace and beauty, come to find all infirmity cease, mental peace return, sincere joy established.

The parallels to the metaphors I’ve laid out regarding experience of the world as someone on the spectrum are, I believe, obvious to trace. There is the sense of being abandoned by those who were supposed to take care of you, leading you to develop the badly-formed coping mechanisms of a child in pain unaware of the nature of their hurting or how their self-defensive contortions make things worse, not better. But there is also the sense of faith and struggle, of camaraderie, and of a secret garden that exists somewhere within the manor of evil, if only you can find the key to access it.

It also happens, coincidentally, to sound a great deal like a doom metal epic or a progressive metal concept record or a King Diamond album arc.

Imagine a hose hissing hot color pressed to your face.

It streams out like a kaleidoscopic, terrifying and beautiful, like a lysergic blast threatening to melt away your psyche. It does not melt, however; your mind remains but in distorted and self-alienated form, thoughts no longer connecting cleanly and logically to other thoughts. What remains is an impressionistic and abstract motion and motility. You drift from neuron to neuron across chiral highways via mechanisms of chained metaphor and emotional/experiential motion; the cold logic of reason fails you here in this place. Ironically, the form these motions take assemble themselves into a language and, cruelly, it is the same rigid and static logical forms that failed you, forming an outer crust of the unfeeling philosopher masking the ecstatic beauty and sublime terror of the overly-feeling interior.

(If the connections to heavy metal are beginning to reveal themselves to you, then good. Be patient. This is an assemblage in a language perhaps foreign to you.)

…

…

The issue of autism is less the hyperbole that the vicious, evil, and stupid might lead you to believe. Even if vaccinations could cause autism, which they emphatically do not, life as someone on the spectrum is absolutely not worse than dying of illness. The issue instead is one of communicability and incommunicability, both of self to self and self to other and, from those, other to self.

Ironically, it is easiest to explain the issue of communicability of other-to-self first. The social manners by which we communicate ourselves, our body language and our little tells, the way certain words are emphasized in certain ways at certain times to convey quite different things, the way we say one thing but mean another which implies a third doubly-unspoken thing, are methods which eventually come naturally to people. That is due to the broad if obviously imperfect success of culture reproducing itself within us, a reproduction that forms a causal loop with the mechanisms of our psychology. The human brain and psyche fixate on certain things like the shape and movement of the face, the sound of the human voice, the way people hold and carry their bodies, and so we form secondary and tertiary supplementary language systems in those spaces, ways which often convey starkly important information to get a decent grasp over intended meaning. And if this sounds like a convoluted way to describe how people normally talk to each other, then good, because the alienation and incommunicability arises precisely because people like me have to think in these kinds of terms at this kind of complexity and specific detail to begin to pick up the kinds of secondary and tertiary messages that are communicated easily among others.

To return to one of the earlier metaphors, this is what maps to being trapped inside the thick rubber suit with a distorting glass helmet in a room of smoke. The signs are all there in the world around you and others send and receive them just fine. The issue is that, due to the way you are equipped, that I am equipped, those same signs are sometimes impossibly hard for me to even see, let alone properly receive and process and act on. It’s not that I can’t understand them if they are conveyed another way; but, to people who perhaps aren’t even always conscious of how they use those other kinds of systems and methods to communicate social and personal information, asking them to translate those otherwise unspoken details into spoken ones can be like asking someone to translate their sentences into Greek. The problem, of course, is that without doing this, their social and personal information conveyed by what to them feel like polite truncations and dalliances of thought are instead to me precisely like hearing someone speak in Greek when I only know English. This leads to the question of social burden, of whether it is fair for me to ask for people to explicitly tell me all of their otherwise hidden thoughts and feelings or whether I should work to become more actively sensitive to them via other means, a balancing act on this shared burden that rarely lands exactly where is best for both parties.

The next easiest thing to describe is the alienation and incommunicability of self-to-self. I would not describe myself as more or less feeling than another person in a raw sense of the term. My eyes are not “super eyes” or whatever, nor my skin, my nose, my ears, on and on. I don’t have greater senses than another. But part of how autism works makes more sense when thinking about how a neurotypical brain works. There are structures of the brain that take in raw sense data, every second of every day. This is a marvel to think about sometimes; even when we sleep, every inch of our skin senses pressure and temperature and texture, our body senses time, our eyes mark the contours of light and shadow playing on the back of our eyelids, our ears pluck all sound from the air when not buried deep in pillow, our noses draw deep the scent of sweat and skin and detergent bleeding together. This would be enough to drive you insane if you let it, being constantly aware of every sensation your body undergoes. The sensations are not a greater fidelity but instead a constant stream, like someone ripped your eyelids off and you could never blink or look away every again.

Imagine a hose hissing hot color pressed to your face.

Thankfully, there is a parallel structure of the brain that then filters this raw and undiluted stream of sense data. Some is handed off to brain stem processes, so that our hearts and our lungs and our kidneys and other organs work in sync or as best they can with the sense information we take in. Some are discarded altogether, certain sounds or images or scents or feelings on our skin (“touch” as we know it is better broken down into a number of smaller bundled senses, each with their own designated nerve bundles and endings), all discerned by this part of the brain as broadly unnecessary. Our brains developed, for the most part, in an ingenious manner; they use, among other things, a dialectical approach to decide what sense data is important, comparing a present image against that which is known and taking note of differences when able. This is also how our bodies mark time and why, trapped in a room with no sound and no change, or endless years of going to work and coming home only to do it again, life seems to collapse to a singularity when in fact it has gone on for years. Only sense data that make it through these two gates are then allowed into the conscious mind, which is ironically used by the brain as something close to a garbage dump, where things like the brain stem take care of the standard processes of keeping us alive and telling us when to piss and when to eat and when we’re horny and when we’re tired, while our conscious brain is allowed, like a supervised child, to play about so long as we don’t hurt ourselves.

Even sensations like fear and anxiety and pain are the neurochemical equivalent of a protective parent warning us away from things that could terminate our lives. Ironically, it’s this overgrown protective capacity, the ability to feel pain and fear, that spirals out of control into existential terror, a series of at once totally true and totally useless observations about the immutable suffering of embodiment.

A brain with autism — because autism has more to do with how the brain is wired and developed than anything else — is a brain that has weaker structures for those two gates. They still exist, obviously, otherwise no one on the spectrum would be able to sleep. Likewise, the fact that people on the spectrum forget things, don’t notice things, grow hungry and tired and such without necessarily having to think about it, are all signs that those other structures still work. The issue isn’t that they don’t work full stop but instead are compromised, such that things like intense fixation can occur because the part of the brain that would triage that capacity at the sensory level is turned off. Likewise, it is substantially easier to get massive sensory overload because while a standard operational brain would filter out certain sounds, certain colors, certain lights, certain textures on the skin, many times an autistic brain simply can’t, and so these high-intensity sensations stack until it can feel like overbearing post-orgasmic stimulation, your skin crawling and your body writhing and you wanting nothing in the world more than for it to stop. Like many things, it is not a binary on/off operation nor even an unmarked spectrum like the steady turning of a knob but instead a series of thresholds where crossing each internal gate is like a spiking plateau.

The result of this is that sense data is always shoved front and center. You feel, you have emotions, but the corona of sensation surrounding the interior core of the feeling is so, so bright that you can’t seem to notice anything else. The precise name and nature of feelings, of actions, seems to slip away in this dissolving intensity. There is radiation, pouring out like light from a wound, from many things that would otherwise be exceptionally ordinary to someone not on the spectrum. Sometimes this is wonderful and produces by its intensity a better ability to precisely name those same feelings people not on the spectrum feel albeit in a less defined manner. Sometimes it is agonizing, like a knife into the head. It feels sometimes like I am trapped in a sea of fog, unable to see around me or beyond the limits of my arm, unable even to see my own hand, and then my own emotions and experiences are pressed right against my face such that I can’t make out any details save for the fact that they are consuming me. This presents a two-fold problem. To know myself, I must use distancing and abstracting tools like language to “push myself away from myself,” and only via the distance of abstract language begin to see the shapes and contours of regular things I have thought and felt. Meanwhile, the rest of the world I must pull close to me, lest it be lost in the fog.

Imagine a hose hissing hot color pressed to your face.

The obfuscation of self-to-self is a war of language and symbol; metaphors are an ideal weapon, as are sentences, logical strings, and poetic gestures, because different things cleave best to different sensations, thoughts, experiences. Some things demand a poetic approach so you can know exactly what I am feeling and experiencing while others demand more precise language. Sometimes it isn’t an act of communication but expression, a shared secret language other people on the spectrum seem well-attuned to parsing while others outside find bizarre, off-putting, in turns too stiff and too loose. This ties into the third, harder obfuscation, that of self-to-others, which becomes easy to understand in the context of the other two. There is this constant war of language and symbol and daily practices to gain firm and stable control of what I think and feel meets the parallel war of discerning what, to me, feels like an endlessly shifting sea of unstated, undefined cues that everyone (except me) knows how to navigate perfectly and I get perpetually wrong; it is in that space that I have to mark a path between the things I feel and how others might best understand them, comprehending those two great walls surrounding my mind and theirs.

This, as it turns out, is the foundation of the work of semiotics, whose entire theory of structuralism, deconstruction, and post-structuralism is built around formalizing this problem. It is also off of this fact that perhaps my fixation with philosophy and theology and art can begin to make best sense. Something like semiotics, it turns out, deals directly with something I struggle with every day in my life, the question of how to understand myself, understand others, and communicate between those poles paralleled in fields like hermeneutics, epistemology, semiotics, and the like. These are not pretentious fixations; they only appear so because, to people where these barriers and social/personal problems are less severe, they seem largely unnecessary. But I have gained as much from reading philosophy as I have from therapy in terms of how best to conceive how others view me, how to navigate those issues, how to communicate myself, how to attempt to understand the world. They aren’t geniuses defining the world but the works of people trying to navigate it and, as such, form not an ideal but instead a parallel literature for people whose brains work best in those language sets. For the symbolic and emotional functions of my brain, theology arises, studying religion and spirituality as the greatest shared symbolic images and functions humanity has ever produced, as well as the closely-bound art theory given that it engages with, well, art.

…

…

Art sits, to me, comfortably and equally beside philosophy and theology in terms of its practical function. Art arises from the psyche attempting to parse its experiences ad senses and render them not in the language of logic but in the direct logic of experience and sense, that of aesthetic. Art is free to be as abstract as a color field or the works of Degas, a banana taped to a wall or a Situationist disruption, an ambient installation or a full band playing songs. Philosophy can be read as an art piece (most manifestos, for example, are more aesthetic/art pieces than philosophy, and people tend to be overly negative to them based more on misidentifying them as serious philosophy rather than serious art), and the connected and disconnected theologies of the world can likewise be viewed through the lens of aesthetic, the attempt to encode the pure and raw experience of things into a new experiential form. This insight likewise opens up art to in turn enact philosophy, enact theology, and the other two to do the same, being more like three faces of a constantly spinning abstract crystal of ways we attempt to convey and share thought, feeling and experience rather than wholly separate fields.

It’s also, incidentally, why anyone of one “space” shitting on another is absolutely insanely funny, because it is actually, like many things about life as a human, the ass that shits on the mirror of itself.

Imagine a hose hissing hot color pressed to your face.

From here, I can reiterate a point: I love heavy metal. I love art and philosophy and theology, as stated before, both here and in previous essays I have written. Each is important in the seamless wheel of experience, world, and self. I love literature and film and poetry and fine art and music. I love a lot of kinds of music, very deeply. But I also love heavy metal. Love. I cannot stress this enough: I love heavy metal.

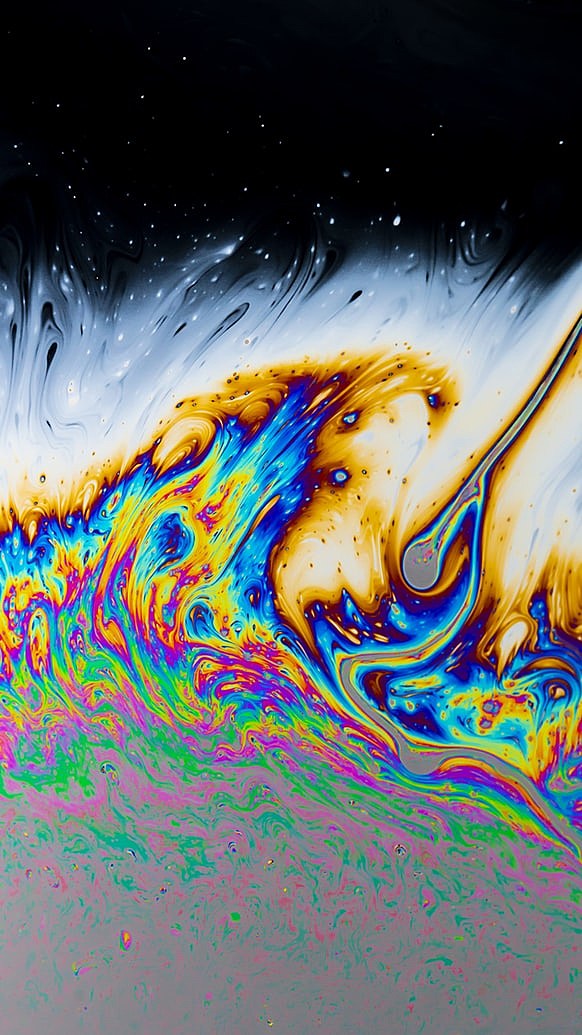

I love heavy metal because of its color, its shape, its gestures, its drama. When I tell you I put on headphones and a new world shimmers real around me, this is tied very deeply not just to being a human (humans, it turns out, via archaeology and history and culture, simply love that art) but also due to my autism. That same sensory sensitivity, where it is so much harder to mute inputs, to where I can feel like my brain is a multi-threaded processor humming and computing endless streams of data and intermingling them and deleting them and rewriting them, is exceptionally conducive to heavy metal. Things like casual virtuosity, the more programmatic and sound-image structural ideas pinched from prog, the vast tonal variety and unbridled intensity all generate a fortress of color.

There is a high comorbidity of autism and synaesthesia. The latter can be caused by a number of things, from funny wiring and connections in the brain to neurological issues regarding nerves actually inputting to the wrong structures of the brain to sensory overload, causing the brain to offload sense data to different parts of itself, generating weird impure perceptions. It’s this last one that people on the spectrum tend to experience the most, again due to the bad sensory gating of our brains, which has the added benefit of making certain things like religious rituals or films or albums or novels sometimes exponentially more impactful because of how quite literally they seem to summon up structure, geometry, color, world, in what amounts to effectively an incredibly intense daydream. It is also something people not on the spectrum can experience; drugs more or less simulate the way simply fucking up the sensory gates of our brains can make the world very, very weird, but so can exceptionally loud music, deeply clashing color, bright lights, or other kinds of sensory overload. This is also part of why concert dramaturgy is shaped the way that it is, to better induce this potential mood in as many as possible.

There are plenty of kinds of music that have the ability to do this to me, but metal does so with an incredible frequency. My previous essay on Devin Townsend’s Addicted discussed its incredible power to speak to me at a time of darkness; my autism is part of what made his particularly dense approach to sonic crafting so intensely rich and wondrous, each little curlicue exploding in lime and crimson. Covers and the imagery a band uses imprints deeply on me and the colors there act as a guide to the more impressionistic and abstract sensations my autistic mind picks up when the headphones are on and the volume is high. This is what compels records like False’s Portent so high for me while some notable records in black metal sometimes do not; I don’t solely respond to what produces that intensity in me, but it is a more common element than anything else. My need for abstracting methodologies and systems to understand myself comes to bear here as well; albums like Ihsahn’s Eremita, which I am destined to one day write about more fully, acted like a sieve for me at a certain place in my life, pulling out of my wounded heart certain shapes and images that I at the time had either refused to see or seen poorly, forcing me to confront both things about myself I needed to witness as well as things in those around me.

The band Isis, who I wrote about in my very first article for this site, produced a series of albums that had the profound ability to make me see the image of my inner heart as if suspended in glass. My essay on Krallice and literally all of I’m Listening to Death Metal (as well as large portions of all of my reviews) are built directly from this interface of my relationship to myself, my relationship to others, my attempts to make those two meet, and my autism. Life on the spectrum can be very lonely, and you can feel alone even when surrounded by people praising you because you are never sure whether you have accurately communicated your inner self, never certain you have been witnessed as you and not a caricature or mischaracterization or mask.

But in heavy metal, I am never lonely. I experience the loneliness I have felt elsewhere in life, but in those intense thresholds where experience of art and experience of self and experience of history bleed together and their barriers are destroyed and all water of being is intermingled into a single gargantuan and devouring river, I am suddenly surrounded by a comforting grace. It doesn’t matter at that moment — who made the art, how it came about. An artist’s intention can be interesting or something galling, horrifying, but that personal ecstatic transformative experience remains. Art, philosophy, and theology are names of different stretches of the same wheel; I am being very literal when I say that these experiences are spiritual to me, enacting in me the same feelings I had as a Christian in church, that Dimensional Bleedthrough and In the Absence of Truth and Symbolic and Ride the Lightning produced in me a humbling and destroying spiritual ecstasy. It sounds admittedly very goofy to say out loud, and I’m tempted to attenuate the statement, but I know what I feel, what role my autism has to play in it, but also how the function of church and meditation is precisely one of controlled stimulation and intensity that can be mirrored elsewhere. These are all liminal states, a corona of the irreal expanses of psyche and perception that glimmer like heat waves off of the material and the real but are not precisely it.

I don’t want to overly mythologize heavy metal or its role to me not because it would make it seem too important to me but because it’s too limiting. Heavy metal is also dumb fun and earthly delight is equal to the ecstasy of heaven. I can be touched by the profound transformative Luciferianism of Ghost one moment, driven to frothing political rage by Napalm Death and Dawn Ray’d and Locrian, and then brought to cackling childlike delight by Gwar and Van Halen and Immolation. Heavy metal is not one thing to me but everything. And if it’s weird seeing Immolation next to Van Halen or Gwar, it is not because they lack profundity or capability in other areas but that pure joy is a profundity, one we often short-sell in the vain and stupid belief that only things of intellect or politics matters. Art is many things and can be many things, and heavy metal too, but it is above all Dionysean, a primal force of experience and sensations, and two interlocking primary functions of experience and sensation are joy and sorrow.

There’s no end to this thought, at least no clean one. It is ironically hard to discuss the relationship between heavy metal and my life and experiences as someone with autism because I have always been writing about it. Everything I have ever written comes from inside that space; every insight I’ve ever had has passed through its gate. My love of heavy metal arises from it because autism is a name for peculiarities in how my brain is structured, and it is that same brain that experiences heavy metal.

How could I ever love it outside of that?

…

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.

…