Mental Illness is not The New Black: The Myth of Devin Townsend

…

After Kanye West released his highly anticipated album The Life Of Pablo, listeners and critics—including MTV’s Molly Lambert—locked onto a lyric from “FML” where Kanye mentions going off of Lexapro, an antidepressant. As one would expect from a walking conversation starter like West, audiences used this line to psychoanalyze his typically erratic behaviour on Twitter as well as the contents of his mess of an album from armchairs across the globe. This narrative is well worn: the idea that an artist’s struggles with their mental health are intrinsically tied to their creative process might be one of the most enduring cliches in music.

Audiences are bloodthirsty for this kind of stuff; the tortured genius edging on madness in order to achieve greatness. Remember Brian Wilson unable to leave his bed and in exchange emerging with Pet Sounds. As long it results in consumable proof of their creativity, we are happy to be voyeurs to an artist’s struggles with their mental health. But for every case of a band like Titus Andronicus or Arsis bearing their souls on albums like The Most Lamentable Tragedy or Starve For The Devil, you’ll just as often find Sinead O’Connor missing. And others you won’t find at all, until it is too late.

Mental illness is not a superpower. It is not a gift that comes with a curse. It is a fact of life and it does not vanish after the record stops spinning.

…

…

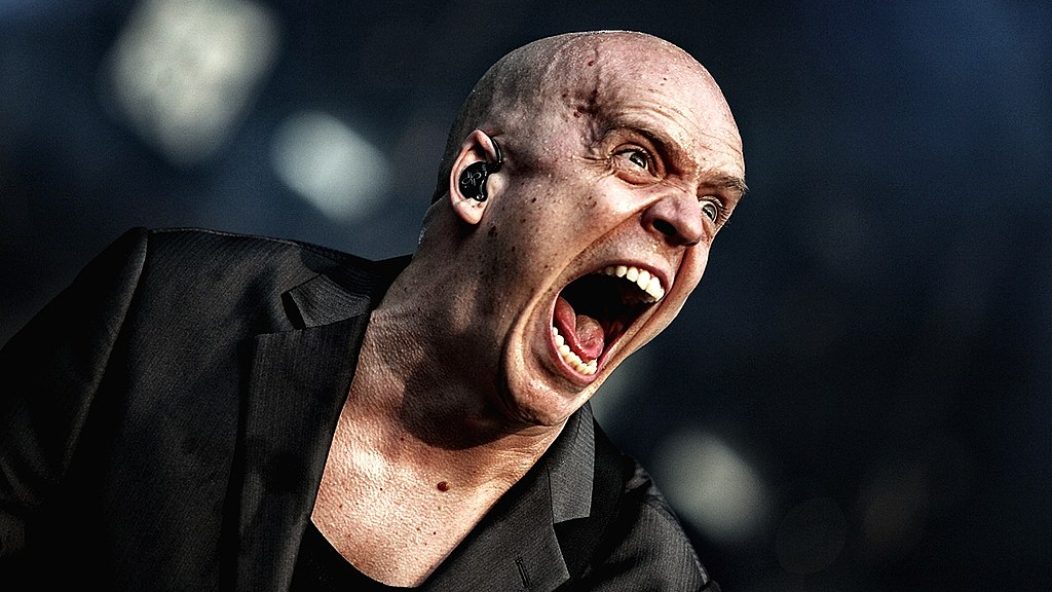

Ten years ago yesterday, Strapping Young Lad released The New Black. It was their fifth and final album. That they even made it to five was a minor miracle. The band, led by singer/songwriter, Devin Townsend, weren’t built with sustainability in mind. After a brief stint singing with Steve Vai at the age of 19, Townsend formed Strapping Young Lad as a way of venting his frustration with the music industry, and for the next ten years their existence hinged on Townsend’s emotional temperance.

They were a vicious live band, powered by Gene Hoglan’s drumming and Townsend’s cocktail of irreverence and unbridled fury behind the mic, but they were also prone to vanishing for years at time. When Exclaim! asked about the inspiration behind the band’s first comeback record, 2003’s SYL, Townsend was ambivalent at best. “I wouldn’t have made another record if it was just for the fans, but Jed, Byron, and Gene wanted to do it.” It was always difficult to tell if Townsend ever wanted to be in Strapping Young Lad, or if he viewed the band as a necessary evil, a way of letting off steam and a counterbalance to his more serene solo work.

As with a lot of prolific musicians, it wasn’t hard to tell when Townsend was really applying himself (like on the unimaginably dense Deconstruction) and when he was simply punching the clock (like on Strapping Young Lad’s self-titled album or his Accelerated Evolution solo release which Townsend himself admits “are kind of bland”). But even if the quality of the band’s work was inconsistent, their tone never was. Strapping Young Lad were, without fail, really fucking angry.

Delivering that anger on a nightly basis is taxing work, and its long term success is predicated on rage being an inexhaustible resource. While that may be true for the Todd Jones’ of the world, it was not the case for Townsend. As the band’s career wore on, Townsend went to increasingly drastic lengths to re-ignite the fury that fueled their early records, abusing drugs and—like Kanye West—going off of his bipolar medication. The resulting record, Alien, is world’s apart from The Life Of Pablo’s manic mogul gospel though. If anything it’s more like Townsend’s Yeezus; a cacophonous and ugly record driven by fatherhood anxiety. Both albums feel like the last gasp of youthful aggression in the face of impending adulthood. This sense of dread is compounded by Townsend’s self-imposed pressure to match the extremity of his youth. “You want to see crazy?” he asks, speaking directly to his audience on “Shitstorm,” “I’ll show you fucking crazy!”

…

…

‘Troubled Genius goes off medication in order to make his masterpiece’ might be one hell of a story, but it’s reckless and legitimately self-destructive behavior. Even if doing so resulted in one Townsend’s best albums, it could just have easily gone south. Townsend was weighing his health and wellbeing against his art. By 2007, the scales shifted the other way, Townsend disbanded Strapping Young Lad, went sober, shaved his signature skullet, and settled down with his wife and child.

In the last decade Townsend has morphed from metal’s court jester to its lovably kooky uncle. He’s been no less productive, releasing a steady stream of music ranging from new age-y ambient to sugary hard rock, even returning to heavy metal with renewed vigor. Still, no matter how often he denies the possibility, questions of a Strapping Young Lad reunion routinely pop up in interviews.

No matter how much music Townsend has produced in the last ten years, the spectre of Strapping Young Lad will always loom over his career. Maybe this is because Strapping Young Lad is where Townsend first made a name for himself in the metal world, but the fascination with the band seems to beyond familiarity and nostalgia. Townsend has become a more versatile and refined songwriting since disbanding Strapping Young Lad, but none of the music he’s released as the Devin Townsend Project feels as electrifying or spontaneous as City.

Townsend’s recent output is immaculately crafted and inspired, like a luxury sports car. At their best Strapping Young Lad were that same sports car launching off the side of the highway while erupting into flames and being struck by lightning. The former might be the safer drive, but the later is more likely to turn heads.

“Name one genius who ain’t crazy,” Kanye raps on “Feedback,” the implication being that the two are inextricably linked. With all due respect to Mr. West, who has earned the platform to talk about the nature of genius, this is a dangerous proposition. Much of rock’s mythology has been built around the belief that flying too close to the sun is worth it if your wings burn bright enough. It is harder to celebrate the artists that knew when to dip back down to more comfortable altitudes, but a culture that holds the value of art over the health and wellbeing of the artist is itself unhealthy. Townsend is the rare Icarus that figured out how to stick the landing. We should be careful how we ask him to take flight again.

…