Life Is Peachy: Nü Metal And America

…

I grew up in suburban Illinois. Elmhurst. Then LaGrange. Both are about a half hour outside of Chicago by train. I spent more years in Elmhurst, an ahistorical quilt of parking lots and cul-de-sacs. Like all the other asphalt tautologies of American suburbia, it was impossible to discern why Elmhurst existed. Not even the patient women who stewarded the town’s museum, located near the 5/3 Bank, facing the train tracks, could provide an answer when I was growing up.

Downtown there’s a parking garage that stands three stories high. When I was a teenager I would smoke cigarettes and stare out into the distance from the garage’s roof. You could see all the way out to Oak Brook, which was a few towns over. I don’t think anyone lived there. It was nothing but an open-air mall and swaths of business parks and offices, palatial and plain at once. Beyond that you could see all the way to the bend in the horizon. It was hard to believe the world didn’t roll on like that forever: a sea of strip malls and off-ramps.

All this happened years before the housing market crash–by then I was exploring my potential as an alcoholically inspired social liability at a small liberal arts college in Vermont. So, when I was growing up, suburbia was everywhere in our minds. The Reagan years were dark, harsh years. Days of hunger, days of theft. Years of stagnation. But by the time Clinton took office it was a new day in America. Politics was over: we just needed some minor adjustment and the market would deliver our dreams to us with the receipts. As Clinton brought prosperity (mostly to white America) and inaugurated an eight year spring break from history, we felt we could anesthetize ourselves from life. Part of that was putting down on a house in the suburbs where nothing was supposed to happen. In our wildest dreams, this is what America dreamed of: nothingness. And one of the expressions of suburban nothingness was nü metal.

Nü metal marks a sonic shift in metal. Since the 1980’s guitar music had been moving from the high-end to the low-end of the sonic spectrum. Nitro’s “Freight Train Coming” is one of the most self-indulgent cuts from the hair metal era and it’s almost all high-end. Listen to the more abrasive records of the time–the Big Four of thrash, for example–and you’ll hear it there, too (consider the bizarre bass-less mix on …And Justice for All). All of these records are about speed and if you want to sound fast high end is the way to go. Too much bass and it’ll sound like a fart.

Then Nirvana happened. And when Nirvana happened, the sound shifted toward the mids. Take their hit “Heart Shaped Box.” Steve Albini recorded this record–though the mix isn’t his. What happened to him is what happened to John Cale’s original mixes of The Stooges’ first record: industry execs caught one whiff and held up their noses. But his signature sound is still present. Albini was infamous for recordings with an abrasive fidelity to the awkward mid-range. It made his albums surprising, jolting, disaffected, and vital–the perfect concoction for the “alternative” explosion that was more about introspection and angst and anxiety than girls, girls, and also girls.

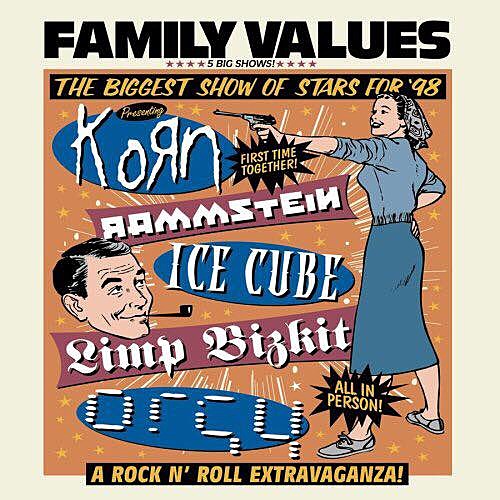

But when Kurt Cobain killed himself the record labels didn’t know what to do next. How to keep the alternative profit geyser flowing? For years hip-hop had been making itself into flyover country, the concrete rhizome of subdivisions sprawling outward from the knotted cities. By various means, hip-hop had made it out into the ‘burbs. At the same time, Pantera had figured out if you wrote songs that were nothing but pay-off riffs with syncopated grooves it drove the kids wild. Bands like Living Colour and Faith No More had already laid the groundwork for funkified, bass-heavy downbeat riffing. Then Korn figured out if you could do all of that and make your bridges go from crazed whisper-babbling about your problems before a breakdown in drop-H tuning to screaming your father’s name then you were bringing something really new to the table. The kids related to psychosis and PTSD, it turns out.

Ross Robinson, producer and godfather of nü metal, intuited this. He saw what was missing. As metal and rock moved from high to low-end, a pendulum swung. Pop music oscillates between two poles: valiant art and unabashed party music. Hair metal to grunge was a swing from party to artsy. So, nü metal, at first, arrived when the pendulum was swinging back half-way between the two. Two examples work for this: Korn’s “Shoots and Ladders” and Limp Bizkit’s “Nookie.” (for the record, Terry Date, another nü metal heavy hitter, produced the latter). Korn’s song is an absolutely bizarre somatic drop in to childhood trauma complete with frothing-at-the-mouth recitals of nursery rhymes. “Nookie,” on the other hand, is about doing it all for the what the nookie the what the nookie. It’s beta-wailing about getting cheated on. It may as well be a party track provided your idea of a party is getting sloshed with your drop-out cousins in Livonia, Michigan who like doing shit like sticking firecrackers up frogs’ asses and breaking all the patio furniture with other patio furniture. Like it or not, grunge could not subsume both elements. It was too self-serious. With nü metal, you can snort your klonopin and have it, too.

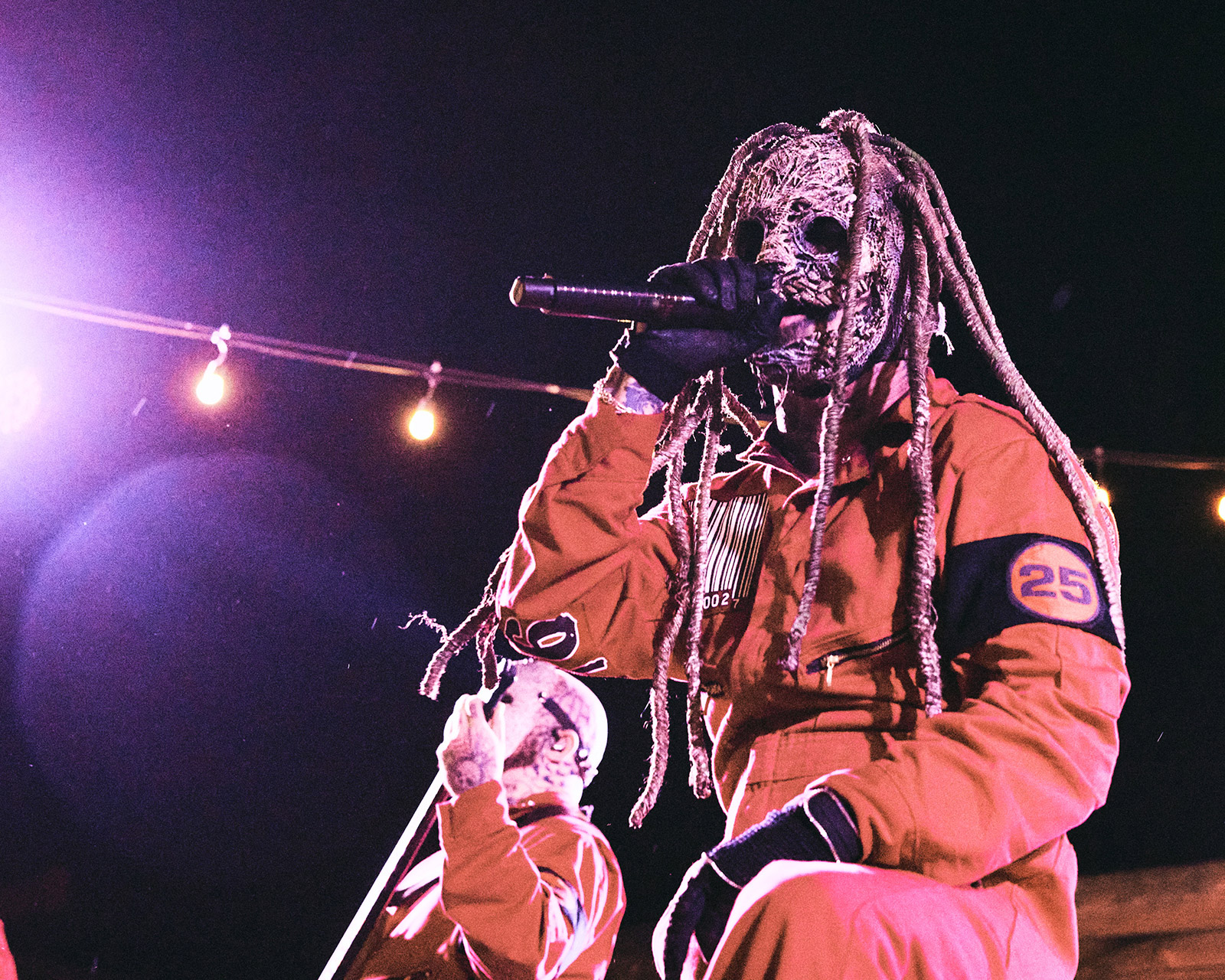

Robinson was in the right place at the right time. He was attracted to Limp Bizkit’s juvenilia (Durst’s songs about punching people in the face and pissing on your neighbor’s lawn) and Korn’s angst (Davis’s naked exhibition of childhood trauma was unheard of in the genre–imagine Dave Mustaine trying to pull that off). He had the uncanny ability to pull exactly these qualities out of the musicians he with whom he worked. For Slipknot’s second album (and the second Robinson produced), Iowa, he pushed singer Corey Taylor to his absolute limit. For the record’s title track he told Taylor to go somewhere he’d never gone before. By the end of the session Taylor had stripped naked, vomited on himself, and cut himself open.

Of these nü metal is made: dropped tunings, hip hop inflections, syncopation, Jackass-style subject matter, Maury Povitch worthy confessional, and the biggest, dumbest, heaviest, poppiest pay-off riffs ever written. It was pure reptile brain. Whatever subtlety grunge’s insouciance and irony possessed, nü metal lacked. Whatever artistry “alt nation” was supposed to renew in the American psyche nü metal denied. This was about hopping out of your hatchback in the 7-11 parking lot to threaten the fourteen year old you swear to fucking god said some shit about your girl and you’re ready to fucking go right now if he wants to go, bitch. This was also the soundtrack for crying alone in your room about how you’re FINE–Fucked up, Insecure, Neurotic, and Emotional, instinctively touching the place where Dad left all the bruises last time. This dual character is, by the way, what’s great about the genre.

And these albums sold.

…

…

There are at least three reasons for nü metal’s popularity: the structure of the music industry at the time; the project and geography of suburbia; and the material conditions of being a teenager in suburbia. The major label model for business was neanderthalithically simple and probably created by Patrick Bateman-style fratbros who came of age roofying co-eds in their Masserattis. What you’d do if you were a major label was this: gobble up as many bands as possible. Shell out millions. Fund albums just for the hell of it. Spend a small fortune on a music video that was half claymation, half the lead singer blinking slowly and shooting up in his mom’s living room next to a Christmas tree. Eventually, you’d score a Nirvana and recoup on the losses from all your other failures. This kind of thinking can only come from wealthy people who love to lecture the poor on the efficiency and efficacy of the market.

This was the marketing strategy that allowed for bands like Coal Chamber to exist, whose first album is the demonstration par excellence of how cookie-cutter and mediocre nü metal quickly became. Pair this with the television media monopolies and MTV and you get a narrow field of options. If they want you to buy nü metal, they’re going to offer nü metal. That’s not to say that these bands didn’t work on their craft or come up with original ideas or create enduring music (Korn and Slipknot have, I would argue, created canonical metal albums), but there was no real “organic” element of its ascendance. As Bart Simpson said, “Making teenagers depressed is like shooting fish in a barrel.” But what if you sold sadness and anger in an Adidas tracksuit with spoken word skits about shitting on someone’s sun roof? Even better.

Still, the kids have to like it. And the kids like things because they speak to them, they illuminate for them their surroundings. Originally, suburbia was a tripartite dream, as historian Dolores Hayden describes it: land + house + community. A uniquely American desire. You want your own plot of land, because what is suburbia except the paint-by-numbers version of Manifest Destiny? You want your own house because you want privacy. But you want community because that’s just a basic human need. It’s easy to see how the first two might ruin the last. And ruin it they did.

By the late nineties, when nü metal was in full bloom, Bill Clinton had repealed the Glass-Steagal Act, a bulwark against bankers dickering with financial instruments in the market and triggering another Great Depression. Now the housing market exploded. The freedom exacerbated the worst tendencies in civil engineering and infrastructure inherent in the suburban project. Instead of thoughtfully designed communities we got a rash of isolated subdivisions whose sole purpose was to be a thoughtful investment, not a commitment to life in a community. So it was a wasteland where nothing was supposed to happen. Every parent and homeowner’s association seemed dedicated to keeping up appearances and making their fiefdom its own Celebration, Florida.

So you have a mass a teens growing up in pointless “towns” with no discernable industry or economy in a nation that had declared itself to have reached the “end of history,” in which no big dreams ought be strived, run by parents dedicated to the fiction that life is a non-event bereft of hardship. Who wouldn’t be miserable? Who wouldn’t be angry?

Look, the given here is that being a teenager is just generally awful. It’s doubtful that that will change. But there are better and worse places to be a teenager. And in many ways suburbia was a cushy place to live. Undeniably. So why did living in suburbia feel so wretched? As America converted more fully to a neoliberal economy, an economy where individual consumer choices and free-market solutions became the remedy for all social ills, it also became a social Darwinist hellscape.

In the inner city, this looked like accelerated Broken Windows policies, an uptick in police presence, an expansion of the private prison industry and the carceral state in general, and a defunding of social services. In suburbia, this looked like over-diagnosis of psychological problems, repressive social codes, the flowering of zero tolerance policies, and the adoption of brutal sink-or-swim ethics for the raising of children. In other words, it was a fundamentally psychologically cruel milieu for kids. And it’s not like there was a lot to do in that tundra of manicured lawns. Anyone who has hung out with bored kids with money (because this generation of teen had more spending power than any that preceded it) knows that things can go from fun to hospital in an instant.

…

…

Nü metal, though not countercultural, at least expressed the glossy resentment of a suburban adolescence. Watch the video for Primer 55’s half-forgotten single “Get Loose” and you’ll see it’s major theme is kids driving around a suburban nowhere doing what? Who knows? The point is, they arrive at the Primer 55 show to get loose and prove that they are indeed down, bitch, down with that fat sound, fat sound. If this seems shallow, tautological, fundamentally meaningless, and kinda dumb, well, that’s because it is. The 1990s were one long spring break from consequences. Or at least that’s often how we think of it.

That’s not the truth of the matter. The 1990s bore witness to a spate of white supremacist and right wing clashes with the government–Ruby Ridge, Waco, the Oklahoma City Bombing and the 1996 Olympic bombing (this was also the year Osama bin Laden declared war on America). There was also another rash of Ted Kaczynski bombings, which led to his arrest and trial. Let’s not forget OJ’s trial, Rodney King and the attendant riots, the Gulf War, and our intervention in the Balkans. Things happened, and in true American style, they did little to inspire self-reflection or meaningful change.

Then on April 20, 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold marched into Columbine High School and opened fire on their classmates. This was one of the first major crises interpreted by the 24 hour news networks. There were countless mistakes in reporting, tendentious and eventually falsified claims, repetition of footage ad nauseum–all hallmarks of the media cycle we now take for granted as part of a mass shooting or bombing. In many ways, we live not in the world 9/11 built, but in the House of Klebold, the House of Harris. Suddenly, unlike when violence erupted, killing black and brown youth in the city, there was a crisis. What was wrong with the kids? Why were they like this? What music were they listening to? I don’t remember anyone asking real questions about the world these boys grew up in. Certainly, they had their own psychological motivations for what they did, but as Franco Berardi points out in his book, Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide, that Harris and Klebold’s act was an incredible expression of the neoliberal, patriarchal, social Darwinism of American suburbia. “The mass murderer is someone who believes in the right of the fittest and the strongest to win in the social game, but he also knows or senses that he is not the fittest not the strongest. So he opts for the only possible act of retaliation and self-assertion: to kill and be killed.” On Harris’s shirt that day were the words “Natural Selection.” It’s hard not to read the Columbine Massacre as a signal that something was rotten in the state of America.

But that’s not the lesson we chose to learn. We looked for scapegoats. Marilyn Manson was convenient. His adjacency to nu metal meant “alternative music” in general got a bad wrap. What we needed was a better, more Puritan approach to culture. Because if anything in American history lacks a tradition of barbarism dressed in the social straightjacket of stupid moralism, it’s definitely not Puritanism. I’m not saying those uptight social reformists were incorrect that the music symbolized something was wrong with America. I’m saying they’re morons for thinking it deviant. The call was coming from inside the house.

A few months later, another shock came. Korn had played the night before. Now Limp Bizkit took the Woodstock stage. Fred Durst, in his signature backwards, red flexfit, scanned the crowd. The sun sank in a cloudless sky. Everyone looked like they were having a good time. People were crowd surfing on plywood–awesome. He had them surf a plank over to him. While a security guard clutched his shirt he stood on the wood just above the heads of the crowd. But then Limp Bizkit moved into their major hit single “Break Stuff.” During the breakdown Durst implored the massive crowd to take all their negative energy, all their aggression, and release it. He figured that meant jumping around, dancing, expelling the darkness to make way for the light. Instead, the crowd ripped more plywood from the festival’s infrastructure, assaulted each other, and raped dozens of women. Later, Durst was charged with inciting a riot.

America had no idea what to make of this. There were more cries of narcissistic decadence (correct), but those who levelled such a claim named this is a symptom of a corrupting counterculture, something outside the mainstream, rather than taking it for what it was: an incredibly large group of young people from the (largely white) middle class terrorizing each other to a song that features the lyrics “I’m like a chainsaw / I’ll skin your ass raw” from an album that sold in the millions. It’s important to read Woodstock ‘99 as a subversion of its progenitor, Woodstock ‘69. The days of peace and love were over. The days of dangerous, beautiful dreams were over. The days of commitment, sacrifice, and regard were over. In their place was an orgy of choices and the echo chamber of narcissistic self-aggrandizement through the conspicuous consumption provided by the market.

Columbine and Woodstock weren’t aberrations. They were confirmations of the rule. They showcased America’s inability to reckon with itself. Nü metal was suitable backdrop for the denial, trafficking as it does in the Janus-face underbelly of Mayberry’s wholesomeness.

But after 1999’s crises for white America, nü metal was pronounced dead–at least that was the feelings amongst bands like Korn and Limp Bizkit. It was a dangerous, juvenile genre that had inspired horrifying catastrophes twice in the same year. Of what use was this? Then, in the fall of 2000, a band from Augora Hills, California released the first single, “One Step Closer to the Edge” from their album Hybrid Theory. Over the next year, Linkin Park released several hit-singles from the record. In tow were younger bands like Papa Roach, Mudvayne, Godsmack, Adema, Hoobastank, Crazy Town, 3 Door Down, Nickelback, Disturbed, Union Underground, etc.

This was the second wave of nü metal. As America rolled into the next century, second wave nü metal arrived as their forebears’ poppy replacement. But if they were poppier, they were also darker. Gone were the hijinks–that was pop-punk’s province now. I have strong memories of skating at the local YMCA with Q101, Chicago’s alternative rock station, piped in through the speakers. My memories of early teen love were scored by some dude from California screaming about killing himself over a re-hash of Iron Maiden’s “Genghis Khan” lead guitar line.

…

…

If derivative and self-parodying at this point, the genre proved resilient. A few months after Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory was released, Apple released the first version of iTunes. In the span of a few years, we’d moved from Napster to the private clampdown on the digital commons,. Free downloading was already on the way out, though it would take many years to perish almost completely, and it would crush the big, dumb Baby Huey that was the major label monopoly under its boot prints. Then in October of 2001, Apple released the first iPod. Our whole relationships with music was changing.

Of course, in between was 9/11, a horrific act that inspired a level of cynicism and idiocy that could have kept us in Vietnam for centuries. Instead, it lead to our commitment to fighting a war in Afghanistan, for whom history has reserved the mysterious nickname “Graveyard of Empires.” A couple years later, for no discernible reason, we committed ourselves to invading Iraq because fuck it, we’re the empire and we do whatever we want. We make our own reality. And the same year we invaded Iraq, Clear Channel began to buy up radio markets nationwide, streamlining their playlists and automating DJs out of their jobs. But even with the monopoly on radio, the internet had mortally wounded the record industry’s ludicrous business strategy. Soon, it would no longer be possible to be the next Korn or Linkin Park. The money just wasn’t there. Instead, there would be a fracturing into different niche pockets of the independent music world.

America was resembling more and more a stripmall featuring an ailing used CD store, a Tae Kwon Do studio of dubious authenticity, a bail bondsman, and the loan shark licking his chops as he watched you sign your subprime. The psychological impact of so much hubris, so much magical thinking, and an absolute levelling of mainstream culture was the second wave of nü metal’s expression. As we became more atomized and solipsistic, we became more uniform.

L.P. Hartley opens his novel The Go-Between with the famous sentence, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” Whenever I put on a nü metal record, say Godsmack’s first album, I realize how unrecognizable much of America is from when I first listened to that record in my older cousin’s upstairs bedroom on a cold Detroit night at three in the morning. In the way that the suburban sprawl appeared endless from the top of the parking garage in my hometown, the American Century looked as if it would roll on ad infinitum.

The summer of 2007, the summer before I left for college, I worked for a catering company. I waitered at a lot of graduation parties for kids who belonged to tax brackets I couldn’t imagine. But one has stuck with me: a subdevelopment vomited up from the depths of Better Homes and Gardens onto the broad plains of nowhere Illinois. It took us hours to get there. I remember thinking, who could even live here? There’s nothing. The party was hosted by developers looking to attract buyers. I can only imagine that in a few months their careers and dreams were dashed, their bank accounts cleared. Whatever dream we held in common in America, to the extent it was ever common, is now dead. There’s something strange about the fact that for me, and likely millions of other Americans, our memories from the Halcyon days were scored by songs like “Bodies” by Drowning Pool, a hit with our troops deployed to the Middle East, and a song banned from radio play in the aftermath of 9/11. Nü metal was the sound of the end of the American century.

The genre won’t come back. Not even the resurgence of JNCO Jeans can resurrect it. It’s a relic from a bygone era of selectively broad prosperity and brutal technocracy. It arose from the blight of Bakersfield, California, Kentucky, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Iowa–flyover country. Whatever grace with which we seemed blessed nü metal imperfectly reminded us was false. The dream was cheap, led-laced. Because in America, we’re not blessed; we’re a house burning down from the inside.

…