Judas Priest's Painkiller Turns 25

…

To analyze Painkiller, we have to consider what makes extreme metal extreme. The factors are speed or lack thereof, vocal stylings, technicality, compositional complexity and production. “Heaviness” is a factor as well, but it’s an arbitrary concept. The standards of extremity in metal have shifted over the years; Stained Class was once one of metal’s most extreme recordings, in the same way that the Bell X-1 was once the fastest aircraft in history.

The album, a high speed piece of history, turns 25 tomorrow.

Painkiller was and is an extreme metal album. What’s more, the record is considered one of metal’s greatest comebacks, which is sort of true. Turbo was Judas Priest’s grab for stardom and a critical low point, whereas Painkiller is largely the opposite. In between those extremes lies Ram It Down, which is half a brilliant album if the Stop button is pressed after “Blood Red Skies”. Ram is a much heavier affair than Turbo, but it’s a commercially oriented ’80s metal record, and the jump to Painkiller’s sound is still shocking.

Spurred on by heavy metal’s increasing extremity, Priest wrote material to fit the era.It wasn’t a forward thinking decision, because Nirvana and co. hadn’t yet shoved thrash and hair metal off of guitar rock’s throne. Priest could easily have released another Screaming for Vengeance/Defenders of the Faith/Ram It Down style album, but didn’t. Instead, they went hard at a time when extreme metal’s popularity and sales were starting to peak.

Personnel changes accompanied the sonic changes, and it’s not clear which was cause and which was effect. Tom Allom, the band’s studio producer since Unleashed in the East, was gone, and so was his ’80s stadium metal style production. He was replaced by Chris Tsangarides, whose credits ranged from Tygers of Pan Tang and Anvil to Sad Wings of Destiny. Dave Holland, the band’s drummer since British Steel, was no longer a member, and neither was the drum machine that flawlessly replaced Holland during the Ram It Down recording sessions. In their respective places sat Scott Travis. Regarding Travis’ credentials and capabilities, he had previously played in Racer X, who were signed to Shrapnel Records.

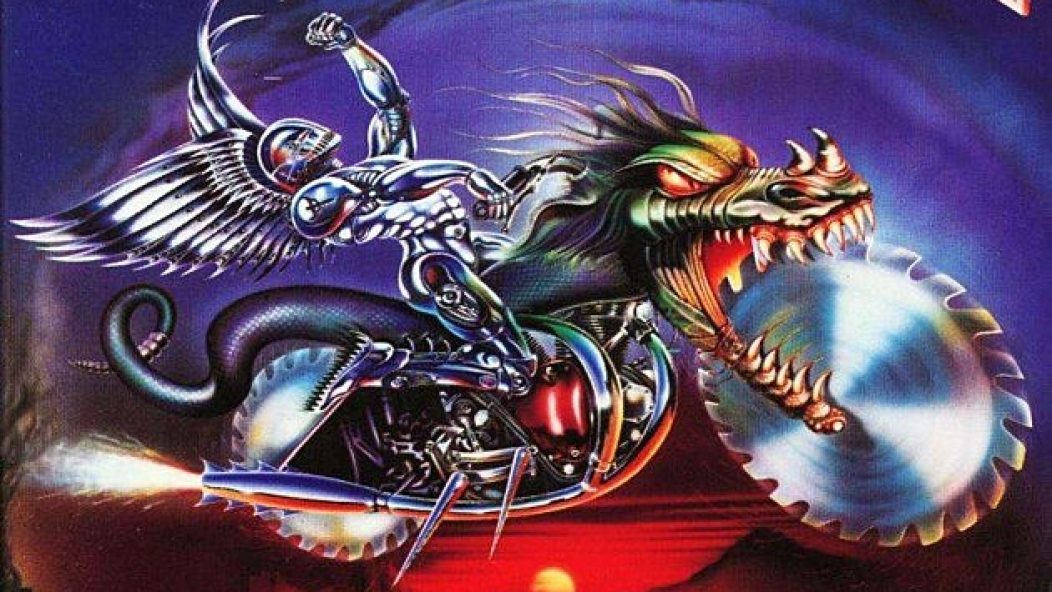

If invoking Shrapnel Records means nothing, then the sixteen second drum solo that opens the record sends the message that Scott Travis can shred, and therefore so can Painkiller. The riffing is a mix of thrash, power metal, and ‘80s traditional metal played at warp speed. It’s recognizably Judas Priest, but tighter, faster, and technical enough to merit extreme metal status, with production to meets that standard as well. The drums are loud and heavy, the guitars dry and gritty, the leads piercing and white hot, and the mix, immaculate. “Cleanly produced” is a pejorative in metal parlance for “commercial and polished”. Painkiller is cleanly produced to show off the material’s numerous edges, and those edges are sharp. The record is the sonic equivalent of a high-def television with the brightness, sharpness and color settings maximized.

Above all of it, Halford performed as never before. The choir boy with the crystalline, angelic falsetto was long gone, as was the ‘80s metal god. In their place was a middle-aged man who was snarling, shrieking, and screaming for something. We keep arriving at the concept of shred, but that’s because it applies here; Halford shreds across the entire record, often using the modal, falsetto, and vocal fry registers in the same track.

It all adds up to an exhausting listen. As with Jane Doe, Obscura, and the good Suffocation records, I love it, but rarely listen because Painkiller is such a demanding experience. The concept of high pitched vocals over aggressive music was not new in 1990. Attacker, Helstar, Sanctuary, Watchtower, and other bands had recorded music in a similar vein, and yet none of their records are as draining and punishing as Painkiller. Primal Fear’s debut, cut from the same cloth and sung by Ralf Scheepers, who unsuccessfully auditioned to replace Halford, is also not nearly as punishing. Painkiller just has it. By the time the record coasts to a halt with “One Shot At Glory,” I’m spent.

Commercially, Painkiller was a success, eventually going Gold. Critically, it was a triumph, both the last great Judas Priest album and one of their career highlights. All of that aside, for better or for worse, it will always be the Priest album for extreme metal fans.

…

…