Interview: Laina Dawes - What Are YOU Doing Here?

. . .

Laina Dawes is someone that I’ve long respected and admired, as both a writer and a friend. She’s been talking excitedly about this project for as long as I’ve known her, and seeing it finally come to fruition is amazing. She’s a woman with a strong voice and a helluva lot to say, so I jumped at the chance to send her a few interview questions and see if I could dig a little deeper into her story.

Gaining her perspective as a black female metalhead, as well as those held by other traditionally marginalized or underrepresented groups within the metal community, is vital for promoting understanding and acceptance within this strange little world we’ve created for ourselves. As vastly different as each individual metaller is, at the end of the day, we’re all in this together. We are brothers of metal and sisters of steel; let’s start acting like it.

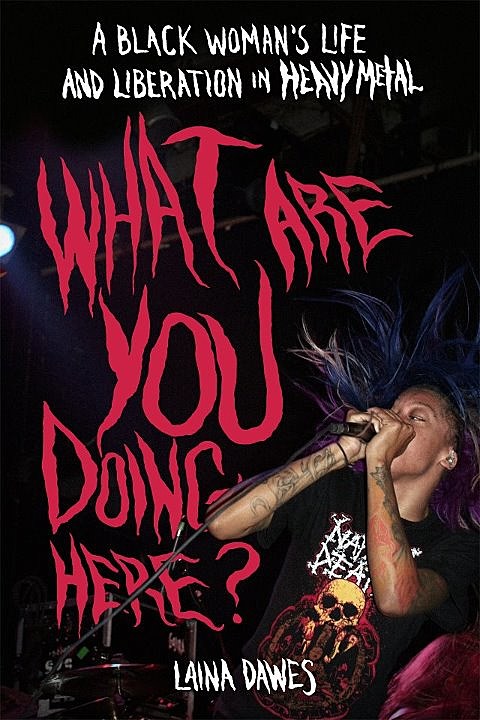

Laina Dawes’ book What Are YOU Doing Here? A Black Woman’s Life and Liberation in Heavy Metal will be released by Bazillion Points this October.

. . .

First off, congratulations are in order! Your book is finally about to see the light of day, which I’d imagine is a hugely proud moment (and a relief, to boot). How long have you been working on this project?

For this particular project, it’s been about four years. Before that I had written a number of articles, blog posts, a radio documentary for CBC Radio and presented a couple of papers at music/academic conferences on the subject.

What made you want to write this book? It’s the first of its kind, and definitely provides a necessary and underrepresented perspective.

The original project was to be a documentary on black women in rock and metal. I had written an essay on Skunk Anansie for an anthology (Marooned: The Next Generation of Desert Island Discs, Da Capo Press, 2007) and Ian Christe (Bazillion Points), who also contributed an essay, approached me and encouraged me to turn my original idea into a book. I started off with six months of research, doing a bit of traveling and talking to colleagues and a few black folks in the metal scene, put together a draft table of contents and started fleshing it out.

Within those four years, there were several drafts, tweaking and conversing with Bazillion Points about the narrative ‘voice’. Should it be academic in tone? Casual? I didn’t want the book to be perceived as a joke, and it took me a long time to get the narrative right, so it could be enjoyed by both metal, hardcore fans and those who might not be into the music, but interested in the subject matter.

How difficult was it to put it all together? Was it hard to track down any of the musicians or other women you interviewed, or was everyone pretty down with the idea from the onset?

It was very difficult, but most of the difficulties were self-imposed, as I’m a bit of an introvert (albeit, an opinionated one) and this project forced me to really reach out and talk to people. In terms of the interviewees, it was not easy, but I was lucky enough to have some great music journalism colleagues who recommended people for me to talk to and a couple of people found me via my blog and volunteered. And then there were people that I stalked at shows! Some I just reached out to as a fan, such as Skin from Skunk Anansie, Sandra St. Victor from the Family Stand, and Alexis Brown from Straight Line Stitch. Being from Canada, I felt that I was pretty out of the loop as there are very few black women in the metal scene here. I primarily focused my research in the States, simply because of demographics and the women were more open to share their experiences.

Not everyone I approached was willing, but I would say that the percentage of that was about 10% – not enough to make me discouraged. As I mention in the book, some were women who have established careers as rock musicians with some big-name artists who were not interested. And those who didn’t see much merit in what I was doing. I am going to guess that they felt uncomfortable talking about their ethnicity because talking about race in any aspect is not the easiest thing to do. I also had a run-in with someone from a metal band who seemed to not get the memo: I’m writing a book on black women, and he was shocked that I was black! Hence, awkward interview.

How old were you when you got into metal? What was it that initially steered you onto the left-hand path, and what led you to seek out ever more extreme sounds?

I was around 7, 8 and saw that horrible movie, “KISS Meets the Phantom of the Opera” on TV. I was really fascinated by their makeup and I asked for and received my first KISS album shortly after. As I grew up in rural Ontario, I had some pretty rough teenage neighbors who were into Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, and some other classic stuff, and I was always into music magazines like Circus, Creem and Hit Parader, so I started researching bands, trading tapes via pen pals and later became obsessed with The Clash, Violent Femmes, Rush, and Judas Priest.

After a brief foray into the Grunge era, I really got into the heavier stuff via Sacred Reich, Corrosion of Conformity, Sepultura, Slayer, and over the years and through friends, started listening to more underground hardcore, thrash and death metal. I’ve always been attracted to the relationship between really aggressive music and the power it emanates, which, because of my background, I really needed (and still need) to feel.

What do you love most about metal?

I love how I feel listening to it. As mentioned before, I’m all about self-empowerment and feeling emotionally in control. I can express those sides of me and emote my rage and frustration, emotions that I cannot express in my every-day life. I feel that it is extremely important to have a forum in which you can let all of that negativity out in a positive way and the energy and power within the music is a perfect accompaniment for that. In addition, I come from a family of classical musicians, so the musical proficiency and variances of musical styles under the metal umbrella is really fascinating to explore.

What was it like growing up as a young black woman in the metal/punk scene? Did you ever encounter outright hostility from fellow heshers? I’m sure it’s something you explore in the book itself, but an anecdote or two would be killer.

I was adopted by a white family at six months, grew up in a predominately rural and all-white environment, so I was used to racial harassment and discrimination from a very young age! I was always really angry as a kid but I turned that internal anger into being very forthright. I did what I wanted to do despite people telling me I didn’t belong or wasn’t good enough. The unwavering belief that I had every right as a human being to go where I wanted and with whom I wanted, is an aspect of my personality that definitely led to the writing of this book. I simply never thought that I shouldn’t be in any environment because of my ethnicity and gender. But was it hard? Yes. Did it hurt? Oh hell to the yes.

However, in 2008 I traveled to Montreal to cover a metal festival for Metal Edge Magazine, and that was a really hostile environment. I was alone, in a city in which I was not that familiar with, and a majority of the attendees seemed to not be from the city – not a lot of people spoke English and from their reaction to me, most likely did not socialize with anyone who didn’t look like them. Someone threw a beer bottle at my head – not the first time that has happened, though! The usual ”fucking nigger” and “don’t you people have your own music?” comments happened within the first few hours I was there. And those were the English ones, the ones I understood. One guy threatened to kick the shit out of me . . . Yeah, great experience.

I actually had to find a quiet space on the festival grounds, sit down and contemplate whether I should run to the hills or stay and do my job. I chose to stay and do my job and the next person that said something to me I challenged him to fight. And continued to do so. I didn’t like feeling scared or sorry for myself. What was funny is that I was really psyched to see some of the bands on that two-day festival and I knew that if I left, I would miss a great line-up and disappoint my editor, which was bad because that was the biggest metal publication I had ever worked for. For these assholes? I think not. But that was the first time when my toughness disappeared and I really questioned my decision as to whether the metal scene was for me.

In the book, I write about some other experiences and some horrible ones that some of my interviewees went through, which even today, makes me really mad. I think the ones that disturb me the most, though, is when white women partake in the racial harassment. That has happened to me in my hometown (Toronto) when I’ve been at a show and I really have to scratch my head over that.

I’ve been reading Toure’s Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness?: What It Means to Be Black Now and was intrigued by the chapter that addressed the notion of “acting black.” Heavy metal has traditionally been a white man’s game (though we are changing that definition!). Have you encountered any animosity or confusion from black folk about your musical interests or involvement in this world? How did your family, friends, and teachers first react to your involvement in this scene and how do they feel about it now, decades down the line?

When I initially approached people about What Are You Doing Here? and how race and racism play a part in how black women participate in the metal, hardcore and punk scenes, there were some people who thought that this book was going to be how evil white people could be. In reality, the majority of resistance to black women participating in these musical cultures stems from their black friends and family members. The appreciation of the music and culture, which might be evident through how someone chooses to dress, or the music that they collect – is seen as a rejection of their blackness, which is an extremely sensitive subject. Interestingly enough, the women I interviewed were some of the most militant black folks I’ve ever met.

Because my parents are white, I never had any issues with them in relation to not being ‘black enough’ and they have always been supportive of my music-listening and writing choices. I have had a lot of resistance from black friends, co-workers and boyfriends who felt that I wasn’t ‘black enough’ for their liking and long ago, some people whom I volunteered with in various anti-racism and social justice organizations – I actually got kicked out of one organization (and politely asked to leave from another) because of my family background and music preferences. I also lost a couple of friends in writing this book who questioned my cultural authenticity, which was disappointing.

In the book I write about the problem within black media outlets in embracing the fact that there are black male and female metal musicians who could do with some media exposure. As one of my interviewees said, there is a vested interest for black-centric publications to regulate what is considered ‘black’ for marketing and branding purposes. Obviously, one of the main hypocrisies about this is that black publications have welcomed non-black artists who are performing black-centric music, or even non-music performing, non-black women who are in relationships with black male musicians, but the hardest music they will accept are from artists like Lenny Kravitz, Prince, Jimi Hendrix (after he was popularized among white audiences) and Living Colour – because they were successful in mainstream society. Notice how they are all men? When Jada Pinkett-Smith did Wicked Wisdom she didn’t even get much, if any coverage from black-centric publications. Anything harder than that is not deemed as worthy of being written about. The lineage from blues music, an African-American musical art form, to rock and heavy metal is detailed in the book. The rejection of metal music and culture can be quite hurtful to black women fans and musicians, but it is the stereotype about the people who are within it: i.e racist rednecks and the fact that not everyone likes these music genres are what make people pause.

Why do you think extreme metal is such a white, male-dominated subculture? What about this music is so good at keeping girls and people of color away?

I think that it has to do with gender and socioeconomic differences – once upon a time metal was perceived as a music and culture in which men – predominately white, working-class men – could release the pressure/resentment/frustration from not being able to procure the material items in which a capitalist society tells them they need in order to be a normative part of society. It was a venue, a ‘club’ where they could get away from their financial problems, nagging wives, screaming children and indulge in their primal instincts (okay that is a bit over-the top, I admit!) Obviously, because metal is huge in socially and economically disenfranchised countries in which the Anglo population is miniscule, this might not be accurate in explaining why, lets say people in the Middle East are fans, but generally the music serves as a form of escapism from everyday life. It’s loud, and aggressive, which are more masculine traits.

One of my interviewees was telling me about a conversation she had with a white male friend in the hardcore scene, who was having a hard time finding a job because he felt he was getting passed over for ‘minorities’ and women. He felt that the hardcore scene should be a ‘white male-only’ space because it was the only place where they didn’t have to think about women, minorities, and could escape from the horrible, horrible oppression that white men face every day!

As I mentioned before, stereotypes about redneck hillbillies keep women away because of fears of being sexually and racially harassed. But over the years, we are seeing a lot more women at shows, simply because they love the music and get the same pleasure from it as men do and obviously there is an extremely diverse group of men and women who are involved in the scene. What were once considered masculine traits such as aggression, are, in reality, traits that as humans we all share. But it was deemed as not appropriate for women to express those behaviors in public.

In What Are You Doing Here? I argue that for black women who are socially oppressed because of gender and race, the metal, hardcore and punk scenes can serve as a safe space in which they can let their aggressions and frustrations out. There is a tendency to generalize about our intelligence, our mannerisms, our physical attributes and our sexual habits. We are not all from the ‘ghetto’ and we are not ashamed of who we are and what we look like. The women I interviewed all said that the heavy music scenes they were into helped them feel that they could temporarily eschew these stereotypes and simply be themselves and recognized for their individual traits without being frowned upon and in some cases, without getting arrested! The problem is, what happens when the racial and gendered stereotypes enter these spaces of comfort and enjoyment?

During the course of your career, and especially in terms of writing this book, you encountered and spoke with many women of color who love and live this music. What are a few of your favorite stories that they shared with you?

There wasn’t one particular story that stood out for me – actually, talking to Dallas Coyle (ex-God Forbid) and my friend Kevin Stewart-Panko from Decibel who I spoke to during the research phase, was interesting, as they shared some thoughts from a male point of view that had me thinking, “WTF?” The best aspect of interviewing was finding out the similarities in the experiences we have all shared, and I actually became very close friends with a few of them. Those similarities were really key in how this book turned out, and because these scenes can be extremely lonely – a lot of people, including myself have very few, if any black male or female friends interested in the same music – it was a really cool bonding experience. We could chat about the hot white metal or punk musicians we had crushes on, and there was no judgment. We could share instances of racism we had experienced that we could not share with anyone because of the fear that no one else would really understand how devastating it was to us. While in a perfect world we choose our friends because of their individual traits and not physical similarities, I really appreciate the wonderful women and men I was able to talk to and hopefully, lasting relationships will come out of this experience.

As a female metal journalist, you and your peers are still often seen as something of a “novelty” (as ridiculous as that is). How have people reacted to you throughout your writing career? I know the wretched depths that comment sections can spiral down into, but I’d imagine you’ve also been met with messages of appreciation and relief – “there’s someone else like me!” – from girls and women in this scene.

I’ve always felt like an outsider, especially growing up where and how I did, so getting involved in metal music journalism wasn’t much of a soul-shocking experience. In some ways, I’ve been extremely lucky because I have met established metal journalists, photographers and other people involved in the scene who have been really cool. Do they see me as a novelty? Perhaps, but they have been really supportive – to my face, that is. Have I had to prove myself? Oh yeah . . . to a point. But I work my ass off and refuse to suck up to anyone. It’s not worth challenging my self-respect and anything I have achieved is because I have put in my time as a journalist and a fan.

I have been introduced to a few metal musicians who will not speak or look at me, and there have been a few who have looked at me standing in the photo pit and are completely stunned. From interviewing other black female journalists and photographers who had the same experiences, ignoring people is a very passive-aggressive way of letting you know that you do not have the social cache for them to converse with. Unfortunately I’ve had a few people who have done some things that have made me extremely angry, but I am pretty passionate about what I do, so I have to let that shit go. There are way more positives than negatives.

My female colleagues have for the most part, been really cool and while I’m not going to scream “vagina vagina!!!” at the top of my lungs, that camaraderie is extremely important. I admire strong, talented writers and people who are investigating interesting topics or looking at issues from a different perspective – not just those in which I share the same genitalia. But I do believe in reaching out and trying to support my fellow female journalists when they have created something cool and/or been unfairly criticized, especially when the criticisms are misogynist in nature. While it shows more about the personality and maturity of the commenter, it is still out of bounds and hurtful, as regardless of how hard you work or how good your writing is, if they disagree with your assertions it all boils down to what you have between your legs.

How did you get into music writing in the first place? What are some of your most memorable interviews/pieces, and what publications do you currently write for?

Since my preteen years when I collected Circus and Hit Parader magazines, I’ve always wanted to write about rock and metal, but I started off writing investigative pieces op/eds on racism and social justice issues because I thought back then that as a black girl, there was no way in hell I would ever be given the opportunity. After I finished university, I started writing for a few hip hop and urban online publications, but got bored pretty quickly and eventually started reviewing alternative rock bands. I met the former editor for Metal Edge Magazine at a music conference in 2005, and eventually started writing for the magazine in 2008.

My most memorable interview was hands down, Judas Priest’s Rob Halford, simply because I’ve been an admirer since I was 12. I also interviewed Oxbow’s Eugene Robinson for another publication and that was awe-inspiring, and Voivod’s Away, who was really cool. For What Are You Doing Here? interviewing Skin from Skunk Anansie and The Family Stand’s Sandra St. Victor were huge, because I admire both of them.

Because of the book I haven’t been doing much lately, but I write album and concert reviews and provide photos for Exclaim! Canada’s Aggressive Tendencies section and occasionally for Hellbound.ca, and I’m going to start writing for Bitch magazine this fall. I’ve also been a contributing editor at Blogher.com for over six years, writing on race and ethnicity issues.

What does feminism mean to you? Do you think there is a place for feminist thought within the heavy metal culture?

Oy vey. I don’t consider myself a ‘feminist,’ as I don’t adhere to the structured ‘movement’ and how it was conceived – off the backs of women of color – but I certainly agree with the general principles of equality. My issue is that the movement was conceived as a ‘catch-all’ movement, inspired for and by middle-class, able-bodied, heterosexual white women and that is alienating to a lot of people – men included. Is there a place for feminist thought within the metal scene? Definitely, but how? In what way? We have to go beyond writing articles that simply criticize men or focus on a specific sexist incident within the scene or on something a clueless male journalist has written– it does nothing. We need to think about ways in which we can constructively make the metal scene a totally inclusive space for everyone.

I am just as turned off of the “Hottest Chicks in…..” bullshit but why are women posing for Revolver magazine? Why are women posing naked in Guitar World, using a guitar to cover their private parts? Why are my white female colleagues not writing about how racism or anti-Semitism affects their sisters in the scene? Why am I seeing half-naked women backstage at Maryland Deathfest? There are women that are obviously capitalizing off their sexuality and benefiting off the “groupie-slut” stereotype, and we have to remember that there are specific issues that affect women of color in which white women are immune from – and benefit from. We have a long way to go, but women need to stop being part of the problem and start being constructive in the solution if we expect to see any relevant changes.

What’s your favorite album to listen to while writing? What’s your favorite album, period?

Right now, I have Mike Scheidt’s Stay Awake on heavy rotation. I also love Ufomammut’s Oro: Opus Primum, the Witchcraft reissues, Karma to Burn, and Pallbearer’s Sorrow and Extinction. They are heavy but smooth enough to still concentrate on work. I have several favorite albums. I’d have to say Judas Priest’s Screaming for Vengeance was my favorite when I was younger, but I also loved Slayer’s God Hates Us All, Sepultura’s Roots, and Mastodon’s Remission. The reason being is that I can remember how my body reacted the first time I heard them. I think the band Lesbian is amazing, and I am also seriously digging Dragged into Sunlight right now.

What do you hope to accomplish with What Are YOU Doing Here??

I hope it provides a unique perspective as to how people utilize heavy music to assert their individuality and to find freedom – temporary or not – from the outside world. Black women have the right to consume, enjoy and participate in heavy music cultures like everyone else. I met a few young black people who were afraid to go to shows, afraid that they would be alone and might be assaulted, or be ostracized by their friends and family members. I’m hoping that my experiences and the experiences from women musicians and fans in the scene will encourage them to get out there and really participate. As you know, the live performance and the camaraderie with like-minded people is such an integral part of really enjoying music, and it’s a shame that some are too afraid to go.

…

PREORDER What Are YOU Doing Here?

…