For the Fun of It: An Interview with Deadlift Lolita

…

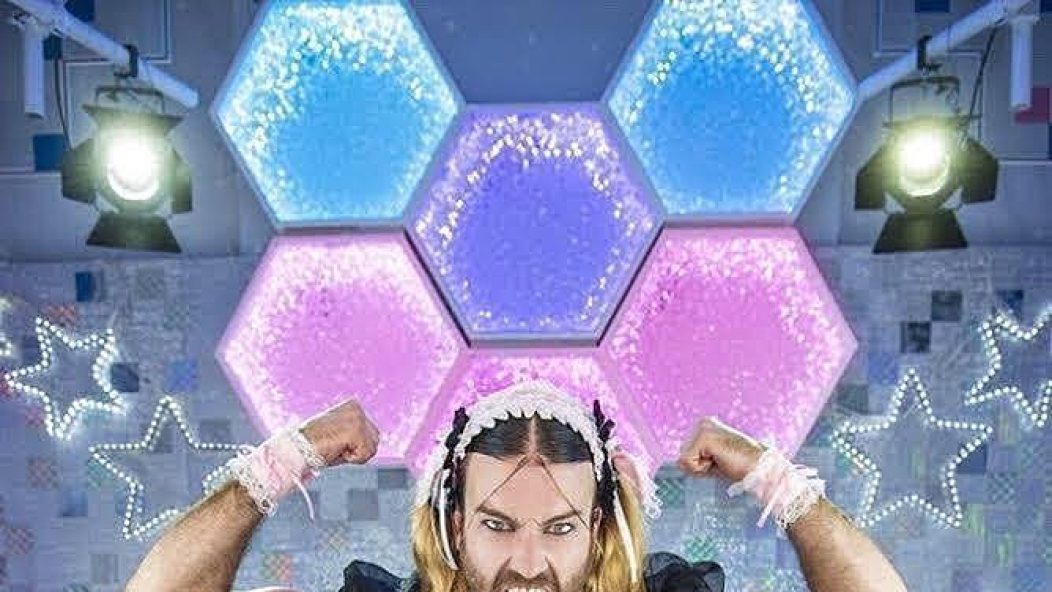

So, this is a thing: a cross-dressing Australian chap who pro-wrestles with a petite yet buff Japanese girl on stage to breakdown-core/J-pop crossover tunes. He’s named Ladybeard, she’s named Reika, and they’re called Deadlift Lolita. Slaying their enemies with a contagiously positive attitude and unabashed style, the duo are guided by ridiculousness and fun, not hate or darkness. As both the thesis and antithesis of “extreme” metal, Deadlift Lolita finds itself at a contentious but ultimately revealing intersection.

Deadlift Lolita focuses solely on experience versus raw content, while most other metal is a balance of the two. Musically, there’s not much to decode — attempting to do so would divert from the point anyway. Ladybeard and Reika’s showtime antics/theatrics are designed for one thing: making you smile. But it’s not a gimmick. Featuring professional production, complex choreography, and vivid aesthetics, Deadlift Lolita is a genuine delight. There’s heart and soul behind the silliness.

Ladybeard and Reika are consumed by their vision for metal’s role in pop music, borrowing metal’s penchant for the extreme and using it to amplify pop’s charisma and style. This approach is both pragmatic and inspired, in many ways Deadlift Lolita makes complete sense despite its apparent senselessness. In fact, Deadlift Lolita is an “extreme” metal band, true to the tag’s spirit, staring convention in the face and then completely flooring it with an overly dramatic drop-kick.

It was our pleasure to hold an extensive conversation with Ladybeard and Reika about how Deadlift Lolita fits into the metal world at large, using the band as lens for culture and self-expression. We also discussed prejudice and closed-mindedness, which for obvious reasons are contestants against Deadlift Lolita’s meaningful existence. Atypical of most metal, but at the same time metal-as-fuck, both Ladybeard and Reika challenge us to reconsider the purpose of boundaries and definitions in the first place.

…

…

Note on the interview: Ladybeard translated questions to Japanese for Reika and then translated (and summarized) her answers to English.

…

What made you guys want to reach out to Invisible Oranges — we’re kind of a pokey metal blog with some serious, dedicated metalheads and don’t really cover the whole j-pop/metal fusion deal. But we found you guys so interesting, and what really popped out was how much fun you guys seem to be having. A lot of the reason we’re serious about metal is because, even though it can be harsh and aggressive or what-have-you, it’s so much fun.

That’s one of the interesting things about our gig, especially in relation to metal — our biggest audience tends to be within the Japanese culture Otaku type/community, and within that community we have fantastic support, so we perform overseas at anime conventions and whatnot. But what’s interesting is from a media coverage perspective, we get a lot of support from metal publications. As soon as we released, we had Metal Hammer, MetalSucks, and Metal Injection then write us up straight away.

It always kind of struck me as kind of confusing, like as you say, heavy metal for me is a “fun” thing; to me, it’s always been much more about what metal does to me in terms of empowerment and the way it makes me feel, and so forth, rather than any kind of music nerd thing. But a lot of metalheads don’t feel that way. The fact that we got so well received by a lot of the metal press — and then their fans, it’s split down the middle, half of them love us and half just despise us and want us dead — we got that kind of reaction from metal publications and I said, “alright, well cool, let’s see if other metal publications are interested in us.” Because I am a metalhead anyway, and look at your blog anyway, I thought to see how you were doing, and if you wanted to talk.

I think groups like us (like Babymetal and whatnot)… I think we’re very important for metal as a whole because the purists hate us, but on either side of the coin, it strengthens things. Like people who are interested in expanding metal into interesting new places, they get on-board with us and have a fantastic time. Similarly, the purists get united in hate against us, so groups like us strengthen the metal scene itself, which is counterintuitive because most purists would say that we would be ruining it.

Reika thinks the interesting about us from a metal perspective is we’re the only ones with this image in metal, as in we’re the only ones who are strong and cute within the metal world, generally. Even in comparison with the other Japanese metal bands like Babymetal and so forth, they’re still rocking a different image and a different gimmick from us. She feels that’s kind of what makes us unique and interesting in the world of metal.

Do you guys feel that having that cute imagery might wrongly offend somebody? Do you feel any backlash or hatred in the “purist” way? It could come down to a variety of things, like the cross-dressing, or even the blast you guys are having on stage — does any hatred present challenges for you, or do you see that as an opportunity?

I’ve always seen it as an opportunity. Firstly, the position of rock ‘n’ roll has always been to challenge the status quo. So, for a group like us who challenges the status quo within rock ‘n’ roll, we’re a lot more rock ‘n’ roll than a lot of the purists are. It’s interesting, I’ve actually received in the entirety of my career, much less hatred than I expected to. Setting out on this journey, I was like, “I’m going to get so much hate, I’m going to have dudes trying to lynch me in alleyways, it’s going to be pure madness.” But I’ve actually been very pleasantly surprised as to how much support I’ve received from metalheads around the world, in Japan and in America.

Reika says she experiences the same thing I experience from metalheads, but she experiences it from the perspective of a Japanese idol. Most pop idols in Japan are younger, thinner, cute little girls, and she’s obviously very cute, but she’s also jacked. So, that’s where she gets her hatred from. She gets fans saying, “that’s not what an idol is supposed to look like, idols are supposed to be small and cute.” So they say the Japanese word which literally means “bad feeling.” But then, of course, on the flip side, there’s a bunch of people who absolutely love it. That tends to be the reaction you get from fans: people have extreme opinions of you. But I think that’s reasonable, because we’re doing something that’s extreme.

…

…

Interesting to bring up culture in general, and Western culture versus Japanese culture — it begs the question of race, because as a white guy working in Japanese culture, I get the feeling that if you were Japanese you might not be as accepted. The difference in race, does that become a kind of token, icon, or fetish of white people?

I feel very much like that. One of the reasons we’ve been so accepted within the Otaku community is, considering most Otaku kids in America, Australia, Europe and so forth, I’m sort of living their dream. I’m a white person who has come to Japan and become famous and now I’m doing this ridiculous performance, and that’s my full-time profession. So I feel to them, I’m sort of like a Jesus figure — “wow, if he can do this, then I can go on and do my dream as well.”

Regarding being a white person in Japan, I think that’s had a huge part in my success. I think it’s had a huge influence on it. So my manager, one of the things she said when I first got here and first got famous, was: “if you had a Japanese person doing the same thing, the exact same in every way, it would not work.” The dynamic changes completely. That’s one of our strong points, that we have the cross-cultural situation, as in we represent both sides of the hemisphere, which is reasonably uncommon. American-born Japanese dudes hanging out with American white dudes is one thing, but a Japanese girl with a white dude in Japan doing our thing (and active all over the world) is really quite rare. I think, like you say, it’s a huge factor in our identity, and something we should cherish.

Reika pretty much echoes the same sentiments as me, like if I were Japanese, it would not work in the same way. She thinks it puts me into a certain position being a white person who speaks Japanese in Japan, but also fluent in English, and who can then travel the world and do shows. I would agree with that, and regarding the group, the fact that we are together strengthens that sense, because then my foreign-ness in Japan I think goes beyond being a gimmick to being one half of the whole. Having Reika with me strengthens that sense, and strengthens that kind of identity as being “yin to the yang.”

So, your identity in essence is a positive message?

I’d like to think so. As I started my solo career, the message I wanted to give the world was one of “anything’s possible.” If I can make a living doing something as ridiculous as this, then you can be an astronaut, brain surgeon, or whatever you wanted to do. A lot of people have seen my work and reinterpreted it to champion other messages, especially within the LGBT community, and I think that’s fantastic. I’m perfectly happy to be a hero for anyone else. But from my perspective, that was the kind of message I wanted to give people. I used to live in Hong Kong, where I saw all these young Chinese kids with huge dreams, but none of them acted on them because their parents were telling them, “no, you can’t be an astronaut, you have to be a lawyer.” I could kind of see the death in their eyes when talking about it.

I wanted to talk about the music too, because people who read Invisible Oranges might scrutinize and tear apart music — I’m more about what it feels like to experience it. I haven’t seen you guys perform, but I’ve seen the videos and you have a very active and aggressive performance, especially during the metal parts. But there’s also dancing, jolly singing, the whole nine yards. How do see the overlap between the aggression and the the quote-unquote seriousness of metal with the more lighthearted, upbeat, popularized way of Japanese pop?

I think that’s a huge part of the joy of the whole thing. From the audience’s perspective, the enjoyment in watching the show and consuming the work is that it’s schizophrenic in that sense. The reason I’ve always liked metal is because it makes me feel powerful. When I was young, I gut bullied a lot, I was a younger brother, and I got my ass kicked all the time, so I felt powerless generally in the world around me. So, metal was my safe haven that I could go to that would make me feel powerful. But at the same time, I also love pop music, because that makes me feel happy.

Those are both two very positive feelings for me — feeling powerful and like I could smash anyone who gets in my way, but also feeling happy and joyous and so forth. Putting the two of them together is really an expression of both the most wonderful and most driving forces in my life, because the rage in metal — there’s still plenty of rage and whatnot — kind of sits underneath the happiness and joy of the pop sound as kind of a fueling fire. I think the two work very well together, especially when snapping back and forth. To the ear, I think most people would say it’s abrasive, but I don’t think that’s the right term — it’s more dynamic. The feeling changes so dramatically. I think it’s incredibly pleasurable to listen to, because one is built into the other.

Reika just made the greatest comparison ever. She said, at the moment in Japan, there’s a popular trend within food called Amakara which literally means “sweet and spicy.” So I guess things like chili-flavored chocolate. She’s comparing us with chili-flavored chocolate, which of course has a taste and an impact unlike that of anything else. If you had only the spice, or only the sweet, they would not deliver the same effect. That’s Reika’s take on our sound, and the role that it has in the world.

You talk about impact and the show, and an important part of Ladybeard is pro wrestling. What draws me to metal is theatrics and pantomime and drama — I like the intensity, I like the live experience, I like it when someone doesn’t just play the music but they put on a show. It’s a demonstration, it’s a performance. What is it about pro wrestling and this kind of music that match?

I agree with you, part of the appeal of metal has always been the stage shows and the performances. I’ve always felt like if you’re not putting on a performance, then there’s no reason for me to come to your show because I can sit at home and listen to the CD and it’ll be the same thing, only more polished. For me, the theatrics and the performance of the live show has always been pretty much number one — in fact, in a lot of ways, more important than the music. That’s obviously a very contentious opinion to have, especially to metalheads as a lot of them are so music-centric.

I’ve always thought in terms of the experience for the audience, because I really feel, as an entertainer, the essence of your job is to serve the audience. The audience has paid, say, $50 to come to your show — I need to give them $50 worth of emotional value in exchange. That means, from my perspective anyway, creating a fantastic show and giving them an emotional experience that they won’t ever forget. Pro wrestling is obviously a fantastic thing for that.

You didn’t see our show in Chicago — but this time, we were doing our thing on stage, and a wrestler came on and assaulted both of us, and we had to have a huge fight with him. We fought out through the audience, I moonsaulted off a speaker stack onto him, frickin’ suplex’d him, it was madness. At the end, Reika and I both give him the hip-toss and the elbow-drop, and then she throws him out of there and we get back to the show.

We go away from our shows and people consistently say, “that was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen,” and after the show they’ll come to fan service and say, “that wrestling that happened was out of control, that blew my mind.” And you can feel the total difference in energy between the first half of the show when we haven’t done the wrestling yet and the second half once we have.

Pro wrestling in particular, there’s something about performed combat and performed violence which is particular visceral for human beings. It’s something we can all relate to. I think the struggle of good versus evil is something we can all relate too. In that sense, pro wrestling is the perfect bedfellow for metal, because part of the joy of metal is embracing both your dark side and your light side. It unleashes the demon within you, but that breaks you through into a new level of hope, as it were. Pro wrestling is quite the perfect counterpart to metal, and indeed what we do. Both of us are wrestlers in the ring — it wouldn’t make any sense for us to not wrestle anyway.

Reika’s answer, in part, refers to the audience’s experience as well. She thinks for most idols — what we are, our style of performance referred to as an “idol performance” in Japan — can’t do the show we do. Most idols sing and dance, and that’s all they do, whereas both of us are pro wrestlers. Our singing and dancing are of course of a different nature: we’re both gym rats, so we can hit a level of intensity that most idols can’t get to, or wouldn’t want to get to. But even though our singing and dancing are so extreme, that’s still looking at a stage. She thinks that once we get the pro wrestling involved — that’s something only we can do, there are no other idols in the Japanese scene who can do that — it separates us and makes the experience of our audience completely unique. But also the fact that we fight through the audience. What normally happens is that we’ll get into a fight, and it’ll spill off stage, and we’ll go through the audience and be grabbing people and pulling on people. It’s total bedlam. Reika feels that that takes things from being a performance that you’re looking at into an interactive experience, and she thinks that’s something that’s quite amazing and she’s very proud to be able to present the audience with that type of experience.

…

…

I’m glad that Reika had mentioned “extreme,” and I think that’s an interesting concept certainly within metal: turning up everything to 11, exaggerating all the aspects/elements, etc. I would go as far as to say that Deadlift Lolita is an “extreme” metal band. I mean, you guys are extreme. And that’s going to get me slaughtered… I’m fucked! But if I’m going by a definition of extreme that I think I could defend, I think that you guys have that characteristic/element and live through it, perform through it. With respect to your fans, what do they need in that level of extreme? What are they searching for? You mentioned the all-encompassing interactive experience. Is this an outlet for them, a way perhaps allowing them to express something about themselves?

That’s actually an excellent question. Like I’ve said before, I’ve always strived to give the audience an experience that they’ve never had before and one that will be completely unforgettable, and one that is absolutely visceral. Like when I’ve gone to a performance which has given me the same feeling — the feeling of hrraaagghhh that was so good! — that’s always been what I’ve strived to give the audience. I essentially see that as my product.

In that sense, what our fans get from the show is firstly that kind of oh my god kind of feeling, which is increasingly difficult to attain in modern life, especially as you get older and things like mortgages take over your life. Really, feelings like that are the real juice and the real joy of being alive. That kind of extreme feeling of joy and excitement I think gives a lot of meaning to the rest of life, to the other 23 hours of the day. Gotta get through it, right? I think our fans come because they like that. There’s an element of the fanbase that responds to the cuteness of things, an element of the fanbase that responds to the workout aspect of things — seeing us as a gym inspiration — and a huge portion of the fans, especially overseas, who just want to have a really good time and have something unexpected happen. That’s a lot of the value we provide.

Let’s see what Reika has to say. First of all, one feels very happy being at our shows. She thinks we give a huge sense of happiness to the audience, and also energy. There’s a Japanese word “genki” which means “full of energy, positivity, and full of life.” She thinks we give that to the audience. Particularly regarding herself, as you can see, she’s adorable — and this girl is the Energizer Bunny on stage. She hits it so hard on stage, she’s jumping in the air, and she’s smiling like this. But her dancing is extremely dynamic. One of the things the fans tell her is that they see her on stage and it makes them feel fantastic. “Genki-ness” is one thing we give the fans.

But the other big thing she thinks is important is we give the fans a place where they can release their stress, a place where there is emotional freedom as such. For instance, Japanese idol culture is pure madness in that what we do — we get on stage and are doing our thing — we have dances where the audience dances with us. You saw the video for “Pump Up Japan” — this dance we have in the chorus, the whole audience is doing that during the show. In, Chicago, we had 1,000 people, all of them frickin’ pumping up, right? It’s awesome. She feels that having her place to go to where you can see the show, the show makes you feel incredibly “genki” and happy and energetic, and then you can also move with us and be part of the group with everyone else in the audience and part of this big family-type experience. She sees that as incredibly important way for people to release their stress and reconnect with their humanity. To get over the stresses and the tribulations of modern life.

Let’s do one last question. This is going to tie back to the first part, talking about more of the underground metal scene. There’s a clear difference between the type of music you guys play and the type of music that underground metalheads listen to. However, they reach the same point. They reach the same kind of feeling, like you mentioned, that almost manic joyousness which comes out when you finally see it and it’s happening and it’s there; a very present and dynamic feeling with the moment. What’s the message to people who don’t recognize that? Maybe they can’t see past the imagery and theatrics, or maybe they don’t like the music itself — but how do you tell people that there’s deeper meaning and a deeper feeling and a real reason why this music exists?

Wow, that’s going to be a hard translation! Oh, it’s an earthquake!

[Editor’s Note:Earthquake. Yes, the exact moment Ladybeard finished translating this ludicrous question for Reika, the camera began to shake. Their faces suddenly drooped with an unsettling look of concern. Luckily, it was a minor quake, and passed quickly. Their faces returned to normal: bright and cheery.]

Sorry, that distracted the balls right out of me. My attitude on this is two-fold: on the one hand, I don’t really mind if metalheads hate us, because I think that’s on the whole good for metal, and good for the strengthening of the metal scene. Second, it doesn’t really bother me if people hate on me anyway. I’m doing my thing and it’s all good. I think, like you said, if we’re bringing the audience to a similar point that their bands are bringing them to, by not taking us seriously as such, by not coming and enjoy yourself at our show, you’re missing out on a potentially really fantastic time. I would encourage to at least once come and clear of your mind of whatever you think and just watch the show, and see how it affects you.

But of course I know that a lot of people are going to give me the bird and say, “nah, eff you and I’m not interested, I listen to this… all of your ‘gay’ shit can get out of here,” and apologies for using that word but I understand that word will be used in this context because it’s used to describe me a lot. My opinion is twofold: on one hand I say, “come and have a go, just try to clear your mind, if by the end of the show you still hate us, fine,” on the other hand I say, “if you hate us, and you’re going to keep hating us, just don’t look.” We’ll just keep doing this with the people who dig it, and that’s fine with us. I would encourage people to come and have a crack, clear their minds.

Let’s get Reika’s take on things. She’s basically saying: don’t knock it till you tried it. Reika thinks that this again refers to Japanese culture — she thinks that because we’re idols, and classed as idols in Japan as pop stars, a lot of metalheads probably write us off without even properly looking at us, just because we fall under that pop umbrella. But they haven’t actually come and seen the show and given us a chance. She would like to encourage everyone to come to the show, or watch the videos, and just have a crack. She compared us with food one more time, there’s this word… like, “I don’t like this food, let’s say it’s seaweed. So I’m not going to eat seaweed for the rest of my life. Even if they discover some new seaweed which tastes like chocolate or something, you’re never going to have anything to do with it.” Her message is: have a go.

With metal, there’s a wall. A lot of people who see metal and say, “I can’t listen to that because there’s screaming,” or, “I can’t listen to that because it’s loud.” But they never break down themselves and expose their bare emotions to it. I think you have to do the same thing for Deadlift Lolita. It just comes down to close-mindedness, an instant rejection or aversion to something that you feel. That’s a powerful emotion, to be honest, and it can drive a lot of people to hateful things. They fail to recognize that the connection you guys make with fans is the same connection that any serious underground metal band is making with their fans. You can cross over and you can learn something from someone else who’s doing it differently. Nobody is doing metal with cross-dressing, pro wrestling, dancing… You can learn something new, and that’s part of the enjoyment of music.

I would agree with that. You know, I don’t mind the closed-mindedness that much, because I think a lot of people, especially metalheads, end up constructing their identity around metalhead-dom. And I think that a huge part of that is obviously what they like, but part of their identity comes from what they don’t like as well. For a lot of people, coming to our show and enjoying it would incite an identity crisis in them. I don’t want to make anyone break down with my work, but at the same time I think maybe you’re missing out on something that you could potentially really enjoy, if you don’t open yourself up a little bit.

…

Follow Deadlift Lolita on Facebook here.

…