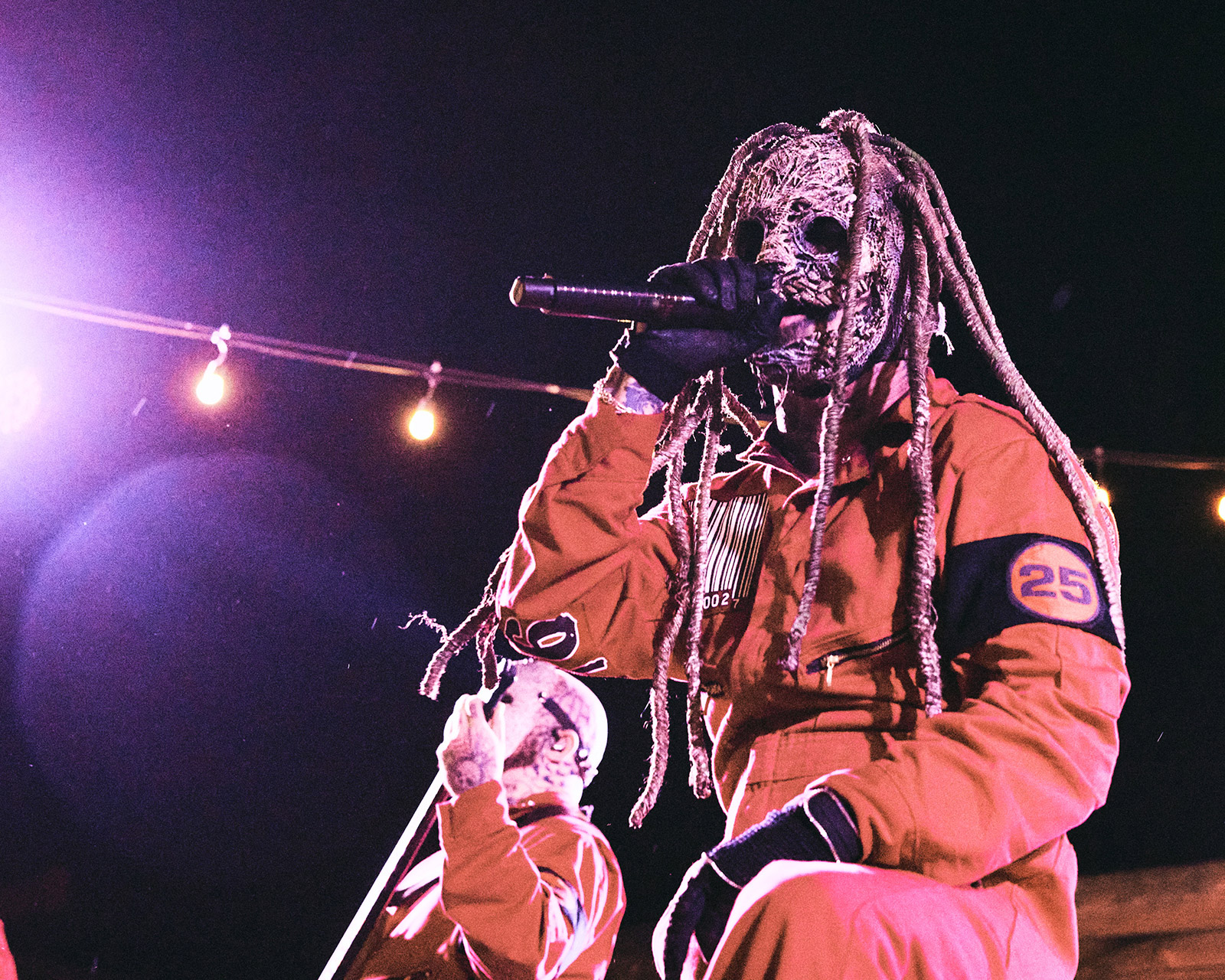

Interview: Ben Falgoust (Goatwhore)

…

Goatwhore is an American extreme metal institution. The Louisiana blackened death bruisers have been shredding faces and praising the name of evil for nearly two decades, and their latest album, Vengeful Ascension, demonstrates that they have no intention of slowing down even for a second. However, on recent albums Goatwhore have kept things interesting by marrying their black metal blasphemy and death metal intensity with a rock ‘n roll swagger and old-school riffs straight out of the Tom G. Warrior playbook. It’s a lethal attack, distinct while also clearly paying homage to its influences.

Vengeful Ascension comes out this Friday, June 23. In preparation for the release, we spoke to Goatwhore’s vocalist/lyricist Ben Falgoust II, also of the sludge-grind legends Soilent Green, about touring, recording, production, the ins and outs of metal vocals, and why Bandcamp is so great for underground extreme metal. Who needs a God when you’ve got Satan?

(This interview has been slightly edited for clarity)

…

Listening to the band’s output over the last decade, there’s been a subtle but obvious shift in style, moving out of a more straightforward black metal attack into something with more death and speed metal influences. Were these changes intentional, or a more organic process that happened album-to-album?

I think it’s been more organic. We went into this band without any intentions besides playing “heavy metal.” In many ways, I think it’s a full circle of our influences coming around. When we started the band, we were more like total Celtic Frost/Venom worship, and that was the foundation that we built things on, that was our early stage. Then the whole Norwegian scene happened, especially Darkthrone, and so around that time we were getting into that stuff and we sounded like that. At the same time, we were still listening to older stuff like Judas Priest and Sabbath, as well as punk and grindcore. So I think it’s a full circle thing where those influences have, over time, come back around to us, but with perhaps a little different perspective than before. When you’ve been in a band for a while and you come back to some of those old records, you often find yourself saying “wow, I never heard this before.” When I was younger I only cared about drinking beers and jamming out, but now we’re able to see the elements in older music from a musician’s angle. As we’ve gone along as a band, certain central influences start to come back up.

The album that you make that has a lot of Celtic Frost influences when you’re 16 is going to sound different from the album you make with Celtic Frost influences when you’re 20 years older. It’s having a more mature perspective on the music.

I agree with that. There is a maturity and a perspective. But I think that with some of these bands that try to take things to a more mature level, they expand their sound out of any strength and aggression. They take a path where they’re like “oh, that was our younger period.” We haven’t really done that. We’ve all gotten better as musicians and writers, but there’s still an element of extremity that has remained even since we were younger.

One of the most defining elements of Goatwhore’s sound is the vocals: how did these evolve and when did you realize that vocals were what you wanted to focus on in the band? Are there any differences in vocal stylings between the band’s formation and now? Do you aim for a different approach to vocals between Goatwhore and Soilent Green?

Oh yeah. When I was doing Soilent Green and Goatwhore at the same time, I tried to make my vocals on each as different as I could. It’s hard, because you have a basic vocal sound. Soilent was distinct from Goatwhore: it touched on different themes lyrically, vocally, and musically. I never took classes for vocals or anything, it was all self-taught. I had moments in my younger years where I blew my throat out and it would take weeks to recover. I learned to focus more on using my diaphragm, really working on ways to project more. Once you can do that, you can really work on ways to make your vocal tone different.

For me, in the era I grew up in, you could hold a mic like three inches from a person’s mouth and the projection would be coming out to the mic. But a lot of vocalists now, they’re up against the mic and they don’t convey any power, you have to raise them up really high in the PA. They can’t really project. When you come off stage, you should feel like you’ve done some serious work, because otherwise you weren’t really doing something. That’s part of the vocal instrument.

…

…

I noticed on Vengeful Ascension that you do a lot more low register vocals than on previous Goatwhore releases.

The first band I was ever in, Paralysis, we did a record back in the day for a label called Grind Core Records. They’d put out some Crowbar releases back then, Accidental Suicide, Broken Hope, all that kind of stuff. Paralysis was more of a death metal band, and most of the vocals I did for it were lower register. After that, I moved away from lows, but as I said before, it’s all come full circle. I’ve always been really into Cannibal Corpse, both Barnes and Corpsegrinder eras, and those particular influences came back.

In 2017, what does Goatwhore’s songwriting process look like? Where do vocals fit in? Is it instruments first, or in the base in the lyrical content? How might that be different from earlier releases?

There’s not really too many differences in how we write songs now. I think that, over time, the real changes have been our evolution as musicians and changes in technology. Our drummer Zack [Simmons] lives in Phoenix, Sammy and I live in New Orleans, and James [Harvey] who plays bass on Vengeful Ascension, he lives out in San Diego. Back in the day, we used to sit there with a jambox and a tape player and record all the riffs for a song at once. It’s always been the music first, then vocals laid over that. Now, over time, I’ve gotten to the point where I can listen to songs and be like “maybe this here needs to be six measures instead of two,” or “I think this riff will have more impact if it goes on a little longer than two measures.” On Vengeful, I did this thing where, instead of the end of a given part going for two measures and a central riff going for four, we switched it up so the ends were four and the central riff was played twice.

Do you think at all of lyrics when you’re planning out where to put vocals in a song, or do the cadences come first?

The cadences come first, but it usually begins with the riffs. Sammy has tons of riffs because, as a band, we don’t throw things away. We keep every riff or idea we write because there’s times where we’re trying to connect two sections on a song and we can’t write anything that works, but we’ll happen to pull this riff up that was written back in, say, 2000, and it’ll fit right in that spot. On a given song, we’ll have elements from several eras of Goatwhore. We don’t throw anything away, because you never know when or where a given riff might fall into place. We’ve written songs where, at the end of the writing process, we weren’t happy with a certain part, so we take that part out and use it later, and there are also songs that we’ve written entirely from scratch.

The same thing applies lyrically: there are some lyrics that date back to my younger days, when I’d just be writing on a napkin at a bar. I just type whatever random ideas I get onto a computer, and when I need inspiration I go back through it all and take pieces that fit with the idea or concept for that song. We’ve gone from sitting in a room with a tape player to Sammy writing a riff, recording it to a computer, and sending it to Zack who has the same program and can change some stuff around. We’ll bounce ideas back and forth so that when we get together to write, record, and rehearse, everyone’s on the same page, which beats sitting in a room for hours at a time going “so what do we do now?”

That goes back to the idea of taking things full-circle. If you have a repository of riffs, maybe in ten years you’ll play them differently than now, maybe the way vocals are laid over them might be different. It’s recontextualizing old conditions to keep them fresh.

Also if I have a riff that might not work the way it was written, but if I slowed it down or sped it up a couple measures it might. If you’re putting a song together at a certain tempo, you can put that riff in and say “oh shit, this fits.” A good example would be on Blood For The Master. We were having such a hard time finding a part for the center of one of the songs, it just wasn’t happening. But then Sammy was going through some parts he had written and he came back with this glow on his face, and he was like “I found the riff!” Right then and there, he just knew that it was the one. There are bands that probably write four or five melodies in practice and never use any of them. Why don’t you just put them away? Music is timeless, just because it’s ten years old doesn’t make it irrelevant.

In a lot of Goatwhore songs, the lyrics lack choruses or what some might call “structure.” Is that intentional? What do you generally think about when you go into writing songs, as far as patterns go?

I remember the first time we worked with Erik Rutan: we went in to record and we gave him the lyrics and said “we’re doing this song and this song.” And Erik was like “Jesus, this is one of your songs? I could take the lyrics from this and do ten Hate Eternal songs!” Since then, I’ve recognized the need to step back. I was listening to a lot of Judas Priest and I realized the power of just letting the riffs speak and then having the vocals come in. I’ll hear a part now and think “this doesn’t need me over,” and I’ve started to pull away a little bit.

As for the whole not-doing-choruses thing, that’s changed too, like on “Chaos Arcane” where there’s sections that repeats and it’s got sort of a chorus part on it. For me, that’s a little different, because I don’t like to do “conventional.” I do it here and there on other songs too, but overall it’s more like I’m telling a short story. I’ve always been real wordy, like always going all in and explaining things, though like I said, I’ve learned the value of going ahead and just letting the riff be the riff.

…

…

I think the “constant” approach is part of what makes Goatwhore unique. So many bands focus on vocals only as an afterthought, whereas, because you’re solely a vocalist, you’re able to bring the vocals to the forefront in the mix.

That’s true, but it also puts me in a tough position where I gotta learn a lotta shit [laughs]. When we put songs from the new record into the set, we spend a lot of time going over them, because I want to get the lyrics in my head, be on top of it, because it is a lot of stuff. When you go into the studio, you’ve got the lyrics and you’re not paying much attention to the material until that new record comes out and you have to relearn stuff you wrote, like “holy shit, I don’t remember any of these even though I was in the studio six months ago!”

Look at Soilent Green: tons of lyrics. I remember one time where we didn’t play together for two years. We went out there, and wasn’t so much like we were in Soilent Green as it was like we were trying to learn Soilent Green songs. We were going over the songs and everyone was asking “which part is this? Where did this go?” But then, by the second or third night, everything was there. It’s like it was hidden somewhere, like “THERE we go!”

Have you introduced a song onstage but gotten the titles mixed up and had the band play another song entirely?

Hmmmm… there might have been. I’ve definitely had it happen where I finish a song, go “now it’s ‘this song,'” then look down at my setlist and go “oh shit, I just skipped two songs.”

Oops.

It’s rock ‘n roll, y’know? I’ve been playing live for 22 years, and I still get really fuckin’ excited when I play live. It doesn’t matter the venue. I think that’s awesome, I don’t wanna give up that aspect of my life. Like, [fakes “tired” voice]”Oh, it’s just a job, here we go. Gotta go onstage in thirty minutes.” I don’t want that.

What are your preferred venues for performing, either in terms of sound or crowd response? What are the advantages of a big fest versus a large club versus a dive bar-type thing?

Personally, I love small venues. It could just be a little PA, but if people are there who know us it’s gonna be an intimate and insane situation. And we still do that, randomly, out on the road. When you play bigger stuff, you got barricades and distance from the audience. The stage is bigger, so you got more terrain to cover. I mean, I do enjoy big fests, because it’s awesome to see that ocean of people in front of you. You’re playing and people are getting into what you’re doing. But there’s nothing like that intimate fuckin’ show at a small venue, where people are tumbling over the monitors, falling all over the place, and everybody’s having a good time. That impact is just immense. Like, four nights in a row at some little fuckin’ craphole doing something unique for the people who’ve supported you over the years.

That seems like a pretty common sentiment among the musicians I’ve talked to for IO over the years. It’s the smaller, more intimate venues that are the more enjoyable to play because of the lack of a barrier between performer and audience.

I saw Judas Priest a couple years back at a casino in Mississippi. It was a smaller venue, like there were seats towards the front and a balcony in the back. You’d stand by the corner of the stage and it would be like three feet between you and Halford. He’s right there! They’re all right there! It wasn’t like when you see them in those bigger arenas. It was funny, because that night, at the end of the set, Halford comes out and says “We don’t normally play a place this size. Don’t say anything to anybody, but I’m having the most fun I’ve had in a long fucking time.”

When y’all plan and then go on tours, what do you look for in touring partners? Obviously the music has to be somewhat congruent, but do you look for a somewhat diverse array of bands?

Ben: We have tons of bands we can go to. We might have met some guys from a band and had them backstage and been like “wow, it would be cool if we could tour.” Then, when it comes time, we have the ability to reach out to them. Of course, everybody can’t just jump up and do a tour: we have to go through a list and say “ok, how about getting this band? What about that band?” Until we get the ones who can do it, and then that’s how it evolves. There isn’t like a “first choice,” either: any of these bands would be cool to tour with. When we did that headlining tour for Constricting Rage of the Merciless, we had Black Breath, Ringworm, and Theories. These bands are extreme, they’re all cool guys, we get along really well, and each one brings something different. It’s more than just black metal. We want bands that fit with us in a certain way.

It’s possible to have a similar attitude without having to stick to one particular sound. In this latest recording/touring cycle, how much will be spent on tour? What are your goals when planning a tour?

I think the longest we’ve ever been out there is nine months. But I think that we’ve pulled back a bit from that, because we figured that we really needed to focus more on Europe and overseas in general: Australia, Indonesia, South America, things like that. We do North America a bunch. There’s also the issue of money, too, especially with the labels and how things are nowadays. There’s just no tour support anymore, the whole industry has shifted to digital. But you work with that: as a band you save up money and you work towards a tour. But some things just tumble upon us: you have to be flexible. If you need the security of knowing what goes on, you’ll never be in a band, because things are random.

There’s some times where you won’t be doing anything. We’re not doing anything in July and August and the record comes out on June 23rd. There’s times where it’s just not happening, and that’s alright. We’re going out with Venom Inc. in September for a full North American tour: we don’t wanna go out in the middle of July and August! You don’t want to overly hit areas, either. So you take these things into account and plan tours around them. Like, in the past when we’ve done Australia, we decide “OK, let’s do Australia. We could do Europe, but we haven’t done Australia for a while and maybe we can go from Australia to Asia or something like that. Being in a band involves having a solid agenda and knowing that things don’t work out perfectly all the time.

You make a plan and then you try to have a degree of flexibility about it.

You gotta be real flexible. It is a fickle business in a lot of ways. I’ve been fortunate that the [non-band] jobs I’ve had have been lenient with my schedule and allow me to leave, and then when I come home I can just work for a while. I can come home and I can pull away from that anxiety of not knowing what’s gonna happen next and focus instead on just working.

When I listen to Goatwhore, one thing I notice is that the production is consistently very crisp. It’s very punchy and clean, unlike a lot of black metal bands who opt for the more lo-fi approach. How much say do you have in how the records end up sounding? What do you and the band generally look for in production, especially on Vengeful Ascension?

We have always tried to get as close as we can to how we sound as a live band. Not necessarily replicate it, but as close as we can get. Now, we do have a say in how things sound, but I wouldn’t say that’s 100% because sometimes you just have to trust the engineer. You gotta get their perspective, because that’s why they’re there. They have the knowledge, so you gotta trust their ability and take their comments as the way forward. It was Erik Rutan who did the last full-length, but we just wanted to do something different on this one. Now we have our sound man, Jarrett Pritchard, and because he’s our sound guy, he understands that tone that comes out of the PA. He adds that element of understanding the PA: drums, guitars, bass, vocals, how you project. We got him involved because he did the last 1349 record, the last couple of Gruesome records, he had the experience.

Beyond him, we got Chris Common to mix the record; Chris is less of a metal producer, but that was a step we were trying to take. We perceive ourselves as a rock ‘n roll band, that whole idea of “black ‘n roll.” It was cool to work with Chris because he’d done stuff like Pelican, Chelsea Wolfe, and things like that. It was a different angle for him to take, but he was really into it, which is awesome. When we were mixing the record, Chris would send mixes and we’d review them. Like, we want the guitars to come up a little more, or we wanna hear the toms when [Zack] does a roll. It’s a symbiotic relationship between us, the mixer, going all the way to mastering.

To what extent is Goatwhore a “Southern” band? How much of a regional influence is there to Goatwhore, and is there still a “Southern” sound or is that becoming diluted by the internet and globalization?

I think the whole “Southern” thing is just an example of people creating a label for a band just because of their location. When I hear people talk about “Southern metal,” they’re often talking about stuff like Down, like bands that use more traditional elements and blend those in with heavy metal. I think we get lumped in with that because of the area that we’re from; we are from the South, but you wouldn’t classify us as Southern metal or Southern rock. If you asked someone, they’d probably say “no, that doesn’t sound like Southern metal.” Now, I also think that nowadays you have bands that are trying to sound exactly like Down, and they’re from somewhere in Iowa, or somewhere in Northern California.

Or like Dopethrone, who are from Canada.

Yeah, exactly. And they’re like “I’m gonna have rebel flags on our art,” which is weird. It’s like the whole weed obsession where people put weed leaves on everything. For me, I’m at the point where I just us want to be considered “extreme metal,” which encompasses a lot of variation. I think that represents us better. You as an individual can determine what kind of box you wanna put us in. Some people feel like they gotta categorize things.

Both in terms of music and of attitude. It’s important to remember that there is that distinction: are you calling something “Southern” because it’s from the South? Is Lamb of God “Southern”? Does Municipal Waste?

I guess technically they would be, wouldn’t they?

Yeah, both of them are from Virginia.

I mean, if you wanna get technical about it. But for people here in Louisiana, Virginia isn’t the South. People from the Deep South, like Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, the top of their state lines is the end of the South.

That’s sort of how it is across the South: I’m currently in North Carolina and there’s a lot of sentiment like that here too.

I was born and raised in Louisiana, and I’m sure there are influences that have come to me through being raised in New Orleans and which are going to color my music. I probably don’t even notice them, it’s all in things that I do. You get a lot of influence from your surroundings.

The final words, as always, are yours.

Oh man, I gotta say the final words? [laughs]

Lemme see… the only thing I can think of, and I don’t even know how to put this, but keep delving into music. It’s one of the defining aspects of enjoying it. Nowadays you have the ability to find any fucking thing out there and have it be top-notch, so definitely do it. To me, Bandcamp is like the new tape-trading, because you got so many bands and it’s a blind thing, and it’ll recommend “if you like A thing, you might like B thing.” It allows people to really dig into stuff online. There’s always something that takes that next step and goes more extreme and heavy. It’s reviving that culture in a modern way, and I just want people to do that.

I want people to support the artists they find on the internet, and I’m cool with downloading, I don’t even care about that, but if you find a band you like, go buy their records, buy their merch. Help them out, because extreme metal is a tough market. These bands all pour a lot of themselves into it. Help them out, that’s what I have to say.

As the “internet age” proceeds, I think it’s less about listening to all the metal that comes your way and more about curation, really delving into sounds and providing that level of support.

The thing I like most about Bandcamp is that a band can put something up for five dollars, but it gives you the ability to pay more. So if I buy a record and I like it, I can go “five dollars? Fuck that!” and give them fifteen dollars.

I think it’s been very good for underground metal to have that way to give back to an artist but also be able to hear them to begin with.

Definitely, I think it’s really good. I just keep following that trail, like “if you listened to this, you might like this,” and so I’ll try that, and just keep going on and on and on til I get exhausted. It’s better than tape-trading because I don’t have to wait for the tape to get here; Bandcamp is a lot faster.

For me, an important aspect of enjoying underground music is that ability to follow those rabbit holes. That sense of exploration is part of the experience.

I agree with that. There’s something about the constant exploration: it’s not the destination, it’s the fuckin’ journey. The majority of listeners who are into more mainstream metal, I don’t feel like they quite understand that for many of the bigger bands, this kind of exploration was their foundation. I’m not saying you have to spend all day at it, but just an hour: you can find so many new bands in an hour. I think that if more mainstream listeners do that, it’ll make the metal scene that much stronger. Being around for twenty-plus years doing metal, you see the ups and downs of it. People say “oh, metal is dead, it’s on its way out,” but it’s not dead, it’s always just an underground thing and every now and then some bands just hop on and push through to the mainstream. But even in the progression from Pantera to Slipknot to today, even that mainstream stuff is becoming more and more extreme.

It’s a dialectic, a constant reinvention. It really is all about bringing it full circle.

That’s what’s kept me in metal all this time. If you’re in the underground scene, it doesn’t get stagnant. The mainstream gets stagnant, because if you have big money in place of art, once that well is dry, it’s onto the next thing. But the underground scene is always evolving, so you don’t get that stagnation. It simply does not get to that point. That’s what’s kept me here. I go back to the music I grew up on, and I still hear different things in those bands. As I get older, I still embrace them just as strongly as I did when I was a kid. It’s nostalgic, but in a way that allows you to move forward as well.

…