Interview - Albert Mudrian (Decibel Magazine)

…

In media, if not in record sales, metal is more popular than it’s ever been. People write about the genre in The New York Times and The Atlantic, as well as on music-focused news sites like Stereogum, Pitchfork and Noisey, not to mention surviving magazines like Terrorizer and Kerrang!. That said, the most powerful editorial voice in media in regards to metal probably belongs to Albert Mudrian, Editor-In-Chief at Decibel Magazine. In his time at the helm, he’s steered the glossy from something beholden to semi-mainstream tastes to a profitable publication that can do things like put obscure one-man black metal bands on the cover. At the same time, he’s spearheaded the Decibel Tour which manages to be a must-see spring tour package each year. Mudrian seldom speaks for himself outside of his brief editor’s notes, but when he does people listen.

Mudrian recently penned an update to his seminal book Choosing Death, an essential guide to the history of the genre. The only place you can buy it is here.

In support of his book, Mudrian and I got on the phone for a lengthy discussion on the scene, his magazine, the Decibel Tour and the very core nature of extreme music, editor to editor.

…

I’ve got to know: why was Pallbearer opening for Converge?

‘Cause Pallbearer is great. ‘Cause I love Pallbearer. That’s why, honestly: I think the band is great. I wanted to do a tour this year that had a little more variety to it than some of the stuff that we’ve done for the past couple years. That’s not to say I haven’t enjoyed the lineups. When we had Cannibal Corpse and Napalm Death and Immolation, that was fucking awesome — an awesome, old-school lineup. Last year, I liked the mix of death metal that we had with Carcass and Noisem and Gorguts. But this year, I just wanted to do something a little bit different. I knew who the headliners were going to be, and then … Even before I knew what everything was going to be, I just kind of wanted Pallbearer on the lineup. I absolutely love the band. I love both albums, I love the demo, I love all of it. I know, for some reason, they are polarizing, which I still don’t understand. I honestly think the only reason they’re polarizing is because they attract fans that are polarizing to fans of extreme music. I think, for a lot of people, they would just be a band that either they like or they don’t like, and they would move on with their lives. But, I think the fact that Pitchfork or something like that pays attention to them immediately casts some aspersions on this band that they’re something less than authentic which, to me, just isn’t true. I don’t see any reason not to think that everything about this band isn’t 100 percent pure and genuine.

I see that. I think that assessment is probably a bit more apt for Deafheaven. Deafheaven’s the only metal show that I’ve been to where the people there made me feel uncomfortable. I was like, “Wow. I am out of my element and I like this band.”

Deafheaven is different, too, because I think there’s an element of self-awareness to all of it where they’re pushing buttons. They’re clearly pushing buttons.

But I like that about them.

I like that, too. Pallbearer isn’t pushing buttons. Pallbearer is just doing what they’re doing.

That’s not my critique with them. This interview isn’t about why Joseph doesn’t get Pallbearer. This is one of my numerous quests in the course of this year. I need someone to help me understand what it is about me that isn’t working with it. ‘Cause I can hear it, and I hear that it’s good, and yet I still don’t like it.

That’s fine. There’s things that don’t move you. Believe me, there are plenty of bands that I’m supposed to love on paper that don’t work for me. I just kind of got to the point where I just moved on. I’m just happy that other people like them, but I just knew that, for me, this doesn’t work. There’s plenty of bands — super important bands that I’m supposed to love. There’s almost movements…

Like what? Give me an example, Albert.

How about thrash metal? How about thrash metal beyond Metallica and Slayer?

You don’t get any of it?

No. Here’s the thing: it’s a generational thing for me. You’ve got to put it in context. I’m 39. I started getting into extreme music when I was 15, 16. So, you’re talking 1990, 1991. I had Metallica tapes, Testament tapes and Megadeth tapes. I liked them, but Metallica was the only one where I was like, “Wow, this is great.” But, to me, Metallica just kind of transcended that genre. Metallica is just Metallica.

Yeah. They’re not a thrash metal band to me.

Right. All these other bands are thrash metal bands. Early to mid 1991, I started getting into death metal. By that time, what interest does thrash metal hold to me when I’m 15, 16 years old? You’ve now kind of crossed over and you’re buying Obituary records, Morbid Angel records, Napalm Death records and things like that. All of sudden, it’s like, “Really? I’m going to sit down and listen to Testament’s Practice What You Preach and this is going to move me in any way?” So, thrash was just this real brief period for me of maybe six to nine months. When you’re 15 or 16 years old, that’s kind of a fucking eternity. But, in the grand scheme of life, it’s a blip on the radar. I didn’t really hear Exodus, besides Fabulous Disaster, at that time. When I’ve gone back and I hear Bonded by Blood, it’s done nothing for me. Nothing.

Well, that’s because Fabulous Disaster is better than Bonded by Blood.

That may be true, but I have no interest in finding out. I get it. I think it’s cool and I understand. I know that, if I was five years older, I would’ve worshipped that shit. But, I wasn’t. This is when I grew up. This is stuff that shaped me, affected me and grabbed a hold of my soul. That’s what I moved on with. So, having the responsibility that I have, I was like, “I need to hear these records. I need to know these records.” I would buy them — I have them all. But, they don’t get played. They’re here. They’re just like reference books in a library. You know?

Yeah.

I know the deal. I get it. But I’m just being honest with it and I’ve tried. So, I just kind of know where it is and I know what it is. It’s like, “Okay, got it. Moving on.”

I get that way about some second-wave black metal. Some of it means nothing to me. I don’t like Darkthrone until they became punks and I don’t like Mayhem until they started taking acid. I like Immortal and Emperor and that’s about it until black metal gets weird. I get exactly what you’re talking about.

I totally understand that, too. That’s what it is. With things that are out, things that are contemporary, it’s difficult to not pay attention to everything that everyone is saying about stuff and form some kind of opinion based on the way other people react to something. Even if it isn’t, like, the basis of the way you feel about something, it makes some kind of impact on you. I get it. I get why Pallbearer or Deafheaven, bands like that — why people have issues with connecting with them. But, at the same time, you’ve just got to work past that stuff. By the same token, if Pallbearer isn’t working for you, it’s not working for you. I don’t try to hammer anybody over the head with anything anymore. It’s like, “If you’re not into this, you’re not into this.” This is why they’re more into At the Gates and Carcass and things like that, too.

I feel the same way. You’re one of the only people that isn’t a musician whose opinion matters because of who you are. Because you run Decibel Magazine, you do get a certain amount of say. So, the example that means the most to me is that when you championed Paradise Lost right before Tragic Idol came out, I saw the profile of that band in America go up — just from being on the cover of Decibel. They’re more of a big deal. I love that band and for most of my life I’ve pulled hairs to get anyone to give a fuck.

That is deeply gratifying to hear. I mean, look: I realize that I’m in a position to have some kind of impact. I don’t know how quantifiable it is. I do know that there are people I meet that tell me they got into a band because they read about in Decibel. I love that; that’s great. One of the opening bands on the tour this year — it might be the Colorado band who I think have “serpents” in their name…

In the Company of Serpents?

Yes. I got turned onto them by my friend Nick Nunns from TRVE Brewing in the Denver area.

Yeah, yeah. They do good stuff.

He turned me onto them and I checked them out. I asked them if they wanted to open the show. One of the two dudes was like, “I’m so psyched to be playing with Vallenfyre. I heard about them from Decibel and I got super into them. It’s so great that we get to go on right before them.” So, I do know those things can happen. I just try not to think about it. I try to keep it really natural and not necessarily have an agenda or be too clinical about all of it. We’re putting Noisem on the cover for the next issue.

Baller.

I think they’re amazing; I think they’re great. Their new album is just vicious. To me, it’s exciting, and that’s just what I want to do. I want to do stuff that’s exciting. I understand that we have a magazine to sell. It’s my job and I have a family, so I want it to be successful. So, there will be, “Hey, here’s a Mastodon cover.” Whatever. You know? I get it. You kind of have to balance it out. But, I think to be able to say, “Here’s a Pallbearer cover. Here’s a Leviathan cover. Here’s a Noisem cover.” I think it’s what I need to do in order to feel like we’re actually doing something. We’re actually part of this movement; we’re actually trying to propel this thing forward. It isn’t as much like, “I’m here to break these bands,” as much as it is, “These things are exciting to me and I have enough respect for my readers to know that the majority of them aren’t idiots. So, I think these things will be exciting to those who haven’t paid full attention to them.” That’s the way I try to approach it. Not so much like, “What can we do with our sphere of influence?” I know there is one, but like I said, it’s not really quantifiable. So, you do what you do and do what you think is right. It serves us well, so I’m just going to stick with it.

I’ve got a running bet going with myself that you’re already sick of this question, but I’ve got to ask it — which is stupid, because I’m getting a reputation as that guy who asks rough questions.

I run a heavy metal magazine, dude. How rough?

…

…

Leviathan cover. I feel rough about it. I want to know where your thought process was with that cover. But, I don’t think I feel rough about it for the same reasons most other people do.

You don’t feel rough about it because there’s a black metal guy with his baby on the cover. You feel rough about it because there was a guy who was accused of — and then plead out to — domestic abuse.

Totally. That’s it.

That is a completely fair argument. There are people on staff who are close friends of mine who were really unhappy with the decision to put Jef on the cover. It’s not like I didn’t think about it. It’s not like I’m like, “Hey! Cool dude.” It was like, “Alright. If we’re going to do this, we’re going to present this story in a way where we acknowledge all of this stuff.” To me, it’s really difficult to start making certain judgements. Yeah, this guy did plead out to this but still denies that any of these events happened. So, you start trying to contextualize them: “Alright, if I’m this guy do I want to risk spending the next 10 to 15 years of my life behind bars for doing something that I know I didn’t do? Look at me: I am this big, tattooed, intense looking guy. If I go in front of a jury, are they going to believe me?” You know? You kind of start thinking about all of these things. I’m not saying that I know that he is guilty of everything that he was accused of or he is innocent of it. I’m just saying that I think there is more than enough doubt … Let’s just say that the system has failed many times before.

Absolutely, yeah.

For me to go by the system that says, “This guy is guilty of this.” … I understand it’s a case-by-case situation and I am by no means trying to marginalize or be dismissive of something as heinous as any kind of domestic abuse. I shouldn’t have to say that’s something that we don’t support. There’s no black and white here, you know? There’s no Varg Vikernes saying, “I killed [Euronymous].” It’s a different situation. Again, people whose opinions I value highly — people who are friends of mine that care about personally — are unhappy with that cover and that decision, and that’s fine. But, I want them to know and I want anybody else to know that it wasn’t a decision I took lightly. I didn’t just think, “Hey, let’s do this and it’ll be cool.” I thought it was a compelling story and I thought that, musically speaking, this guy was a kind of genre-defining artist. Everything just kind of lined up. He was comfortable with us and willing to do stuff with us that he wouldn’t be willing to do with anyone else. So, I was like, “Let’s take the chance.” I’m happy with that. I thought Bennett did a great story and the photos were amazing. Here we are.

I mean, you stuck the landing. I love that story. To me, it was sort of a redemptive thing. I’m less raw about it after having read it than I was when I knew it was coming out. I don’t want this whole interview to be about Jef Whitehead. But, I will say that I was actually on the fence with him until the Decibel story about his last album [True Traitor, True Whore] came out. Then, when I read that story, I was like, “Alright, screw this guy.” But, it made the magazine look great.

Yeah. But, that’s not what it’s about ultimately with us. You know? It’s just trying to paint accurate portraits of where people are at at a certain time. Where’s he at now versus where he was at then, it’s much different. I don’t think people even realize: there’s nothing calculated about this. This is all just something that was kind of organically conceived. The way it turned out was better than any of us realized. Originally, Jef and Stevie were pushing for photographers who were way more esoteric. They wanted something that was really dark. I was like, “No, we can’t do that. We’re a newsstand publication; we don’t do things like this.” We’re not going to do something that puts Jef in a position where he’s uncomfortable and out of his element, but let’s do some portraits. All of sudden, the baby was there. He was like, “Hey, let’s do some shots with the baby.” It was his idea. They turned out amazing, as you saw, and both Jef and our photographer were into the idea for a cover. To me, they are the most compelling photos of the shoot. There was nothing planned. There was never a meeting where we were like, “We’re going to get Jef Whitehead and we’re going to get his baby and we’re going to put them on the cover.” That shit never happened. It just kind of turned out. I think maybe that’s part of it for people too — it’s easy to be cynical about it. There’s nothing calculated. Anyone who thinks this is a big calculated thing is giving us way too much fucking credit.

As an editor of a publication to an editor of a publication: on that level, I did fucking adore that. I adored it — and this is a weird connection to make — almost in the same way that I adored the women in metal cover. I thought, “Look: here, we’re really breaking the image apart.” I love when people are willing to take the stereotype and fuck with it.

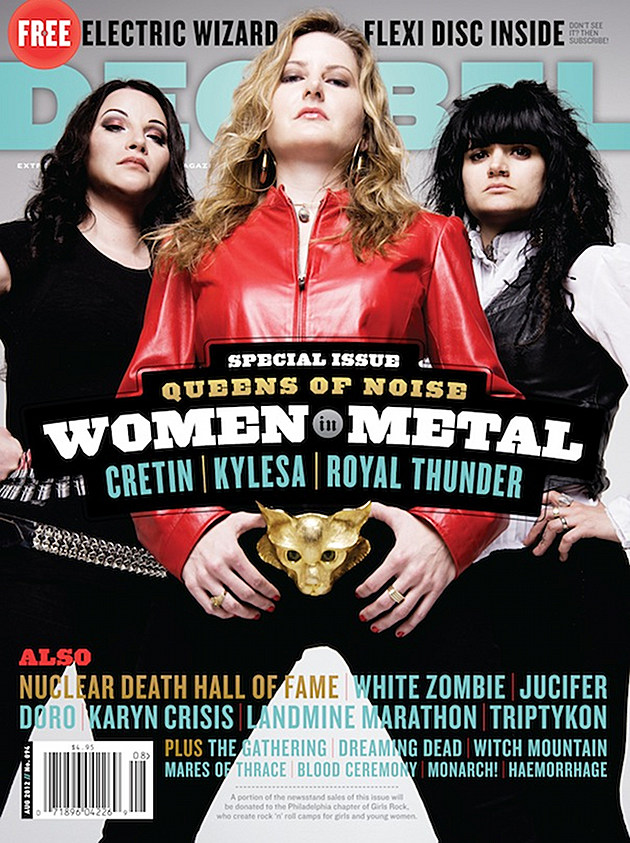

That was very conscious. I knew who I wanted. I knew who I wanted to shoot it. I knew how I wanted people to present themselves. The issue overall, it was all very calculated. In a lot of ways it was reactionary to a lot of things that have been happening in heavy metal for-fucking-ever, and even more recently — over the past five to 10 years with this hot-chicks-ification of the genre. I felt that we’ve definitely taken our shots at the idea of it. We had basically another publication’s continual over-sexualization of women. We’d done that through our Hottest Dudes in Metal and Cutest Kitties in Metal and shit. A lot of people were getting and getting the joke. But, then it got to the point where I was like, “This isn’t fucking funny. This is stupid. I didn’t even realize how stupid this is.” I decided, “I think we should do this. I think it’s time that we stop fucking around.” That was a very calculated thing and the three women that I asked to be on the cover, I asked them personally. We made it happen and I think it turned out great.

…

…

It was an apt moment in time. I severed ties with said other publication over that issue, over my discomfort with that. The women you picked were, in their own ways, all really strong choices. To put Marissa on the cover, in particular, was really, really brave. I felt really good when I looked in my mailbox and that was the cover I saw. I thought, “Subscription well spent, Joseph.”

Well, thank you.

We should maybe, at some point in time, actually talk about your book.

What book?

Your new book. Your new, old book.

Yeah, there’s that thing.

You don’t seem too enthused about it.

No, I am. I just have a lot going on. I’m very enthused about it. Choosing Death is extremely personal and important to me. Now that this version is actually done, and was written under extreme duress — unlike the first version, which I wrote when I was your age — I’m taking a bit of a step back from it and appreciating the fact that I’m 39 and this book has been in my life for 13 years. It’s literally been part of my life for a third of my life now. It means a lot to me. It’s definitely something that’ll be part of my life forever. It’s funny to even think of it like that. It’s not like it’s some enormous fucking bestseller or something like that. It’s just something that I’m personally proud of and that has connected with people. I feel it has the ability to be reinvented as it is right now, hopefully.

This is also a question you’re probably sick of answering, but it seems like an obvious one: it’s a question that begs. Why rewrite the book? Why not do a different book?

Well, here’s the thing: you’re writing a musical history of a movement that has not ended. This wasn’t, like, American hardcore 1980 to 1985. This is something that has existed and continues to thrive these days — not that I was completely unsatisfied with the original. But, I knew the second that the original was out, “Oh, man. There’s so much stuff that’s fucked up in this thing.” There’s so many typos, there’s a few factual inaccuracies and there’s things that you wish you spent more time with, et cetera. It was kind of like, “I hope someday I get a chance to take another whack at this.” So, as the years went on, it’s not like I was able to ever really step away from this music since Choosing Death was released. Choosing Death essentially came out at exactly the same time as issue one of Decibel. So, I have been deep in extreme music and death metal and everything this whole time. It’s not like I haven’t seen everything that’s happened. So, having that front-row seat this whole time, I’ve been able to process things in the movement. To me, it was really clear by around 2007 that another version should exist someday. It just became like, “When’s the best time to do it?” How much time do you want to give it to get enough developments in that it isn’t just like, “Hey, here’s another chapter,” and that’s it. You want to do something that feels like a fuller — I don’t want to see a reimagining of the book because it isn’t that. The 10 original chapters are still there. Yeah, they’re a bit different, but it’s not like it’s a whole new book from scratch. To me, it was just fleshing everything out and making that that was there that much better. I think I was always waiting for that moment when I was like, “Okay, now I can do this.” Basically, the moment that I knew I could justify the existence of another Choosing Death was when Carcass and At the Gates both announced that they were going to reform. That wasn’t the only thing that happened between the release of the book and 2007. I don’t know if that would be justification for it. But, there were a bunch of other things that kind of led to that culmination. There was the development of the old-school movement that had taken place in 2005 through 2007 or technical death metal really becoming its own thing around that period or whatever. There were a lot of developments after Choosing Death was written, let alone printed and distributed in bookstores, to when both At the Gates and Carcass announced within months of each other that they were going to be active bands again. Anyway, you have that in 2007. By that time, Decibel was really taking off. I was like, “How am I going to do this?” You kind of just put it on the backburner and you hope someday a window will occur. Then, in 2011, my wife and I had our first child. Then, it was just like, “Oh. I ain’t fucking touching this right now.” ‘Cause everything is that much crazier. Then, it became October of 2013. We learned that we were going to have a second child. It was pretty clear at that moment that it was now or never. Maybe not necessarily never, but now or five years from now. I didn’t want to wait another five years, so I started working on it. I did my best to try to write it within nine months. I finished it when he was about two or three months old. It took about a year. It was definitely a much different experience: writing and rewriting this. But, once it kind of got going and I was working on some new chapters from scratch, it was not that much different than it was in 2002, or whenever it was, when I was carving those chapters out for the original version.

Maybe you’re one of the only people in the world that’s in a good position to answer this question. I think the cover of Decibel is maybe one of the first places where I first thought of this umbrella term, extreme quote-unquote music. You don’t and I don’t just write about extreme metal. There’s other elements. You did the noise rock issue. There’s even these electronica elements. Those two worlds are finally starting to peak over the fence at one another. What is the thing at the core that separates extreme music from non-extreme music?

I think there’s an element of ferocity that extreme music has that isn’t available in non-extreme music or whatever you’d like to call it: music music, for lack of a better term. That’s not to say that Decibel doesn’t cover things that aren’t extremely extreme because we certainly do. We certainly branch out and often reach over the fence a bit and induct things into the Hall of Fame that might be perceived as less extreme, whether that’s a band like Failure or Living Colour. That raises a few eyebrows. Extreme music is less limiting of a term than just heavy metal or extreme metal, even. Ultimately, at its core, extreme music is metal-based. So, the vast majority of music that’s published in an extreme music publication is going to be metal. But, like you said, it leaves the door open to cover other things, whether it’s something like Swans or Whitehouse or whatever. There is that element of danger and ferocity and rage and aggression that is present in something that is extreme that isn’t necessarily present in something, let’s say, like Failure. Of course there’s elements of anger in the songs — and rage and sadness. I’m sure you can find that on Fantastic Planet on a bunch of the songs. But, I do think it’s that undercurrent that defines extreme music that isn’t the thing that propels, for lack of a better term, music music. That’s just my interpretation of it. It isn’t necessarily to say, “There’s an element of technicality, speed or whatever.” You can listen to a sloppy noise rock band and that, to me, can be more extreme than some over-the-top technical death metal band that’s got an eight-string bass in it. So, it’s become really difficult to put your finger on it. It’s one of those when you hear it kind of things. I think we definitely push the boundaries, in terms of Decibel, anyway, of what’s considered extreme. You can kind of expand the context beyond just music sometimes — like that Living Colour Hall of Fame. There are those instances when those dudes are dealing with such blatant racism. [It was] such a weird position for four young black guys in the ’80s, playing heavy metal. To me, things like that are extreme. Are there blast beats? Nope. Maybe I’m stretching the term and maybe I’m turning it into whatever I want, but at the same time I really believe that it isn’t just a sound. You know?

That’s the cool thing about the term “extreme music”: you get to bend it, whereas metal is, to a greater and lesser extent, a rigid term. Although, the funny thing about metal — and this is something that’s taken me a long time to realize — is that everyone can agree that the term is rigid, but people still have a lot of difficulty knowing where to place the line.

Mhm.

Like, what does or doesn’t define metal. You know? People seem to agree that there’s a line, but I can’t ever find anyone who can agree on what the line is.

Again, that’s a macrocosm of extreme music. So, I get it. It’s a bit up to interpretation. I think that there’s some things that are easily definable because you have bands that define themselves as something. There’s bands that say, “We were a brutal death metal band.” You know? “Okay! You’re metal.” The moment you declare that, as long as you weren’t playing Darkness covers, I’ll believe it. It’s kind of up to the artist sometimes to determine where they want to be. They actually have that power a lot of the time even though they think they don’t. You’ll get the classic, “Oh, whatever anybody wants to call us they can call us.” You know? Fucking bullshit.

Yeah. That’s BS. Here’s another thought. I didn’t get to read the first draft of your book: I literally only have the PDFs of the new version. What struck is me, to a greater and lesser extent, death metal and grind were sort of born from thrash. I’m personally of the opinion that thrash as a genre is sort of inert. It’s dead. Very few people have had any success in pushing it forward past where it is. Vector tries really hard; Skeletonwitch try really hard, too. It’s pretty much just them, and then it’s sort of set. But, death metal’s still going.

Right. And Anthrax’s The Sound of White Noise, of course.

Well, hmm…You want to talk about that line between heavy metal and hard rock? If someone were to say, “The line is Anthrax’s White Noise,” I’d say, “That is an acceptable line.”

Yeah, I think you might be right.

My line is The Black Album. The Black Album is the least heavy you can be; that is the bottom. If it’s less heavy than The Black Album, it is now a rock album.

Yeah. The Black Album is a heavy metal album but I agree. It was produced by Bob Rock, not Bob Metal. You know? You’ve got to reconcile that. Anyway, you were going somewhere with thrash and Choosing Death.

Yeah. Death metal. Why is it death metal and, to a lesser or greater extent, grind are still evolving and changing? Why is that?

I was thinking about that not that long ago. If you did a thrash metal book, it couldn’t really be like Choosing Death. Sadly, you couldn’t do Choosing Thrash, I guess. The style has kind of defined itself by an era. It’s such a tight little box that it fits in and that’s all it can do. Death metal’s ability is to be more expansive and a bit more brave in that sense. Bands can be so far apart from one another in terms of the way they sound and what defines them. I’m not really sure. Yeah, there are elements of thrash in death metal, but it’s the most extreme thrash out there. Those elements are Slayer, Sodom, Kreator and Destruction.

Possessed.

And Possessed. It’s arguable whether Seven Churches is a death metal album or not. So, when you get to the point where you don’t even know whether it’s a death metal album or a thrash metal album, clearly it’s way more extreme than The Not Man. It’s another level of extremity. Once you’ve kind of moved out of that box and you’ve left those influences…Here’s the thing: I think the influences that created grindcore stayed more with them than the influences that created death metal. You’ll hear plenty of death metal bands that still have a little bit of a thrash influence in them. But, people would think of them as thrash bands. Even like, Revocation. If Revocation came out in 1991 people would think they were a death metal band, but death metal has evolved vocally. The vocals have so much to do with it. Death metal vocals are such a part of the landscape. They keep appearing in so many types of metal and rock at this point. Anyway, I’m getting sidetracked. You’re trying to get to the point of why death metal has moved forward while thrash is lasting as almost a time-capsule, nostalgia genre.

For a long time, almost every other subgenre was like that. I really think black metal only started accelerating again in the last, like, eight years.

Eh, I don’t know. Not to get too off-track, but I do remember black metal in the late ’90s: shit was getting weird, dude. Moonfog was making things really, really odd in a good way. It was like, “Wow. What is going on here?” To me, black metal is a much more progressive genre than death metal. I think black metal is able to move itself out and expand itself out in ways that death metal hasn’t, for better or for worse. I don’t love everything that is happening in black metal. I like plenty of it, but not all of it.

Definitely.

I don’t think the question is so much, “Why is death metal so progressive?” as much as “Why is thrash so fucking lame? Why can’t thrash get it together?” I think there’s this hybridization of things, too. The only thing that thrash is ever able to make a hybrid with is either death metal or black metal. You know? It didn’t have anywhere else to go. Think about all the different types of death metal: all the things you can mix death and black metal with. There’s tons of stuff. Whereas thrash is maybe not a primary color. I don’t know what it is. It really believe it isn’t so much, “What makes death metal so malleable?” as much as it is “What makes thrash so rigid?” I’m not even trying to dodge your question. I’m just really thinking about that and trying to think about what it is.

That’s definitely one viable argument. I was having this conversation with Islander, who runs No Clean Singing. The conclusion that I came to is that — and maybe this says, in the way that your assessment of thrash says something about you, I think my answer probably says something about me — life is inherently dark. The genres that persist are the genres that can capture that and ring true for people in some way. I think that the partyness of thrash made people unable to…They can’t find the darkness in it because it’s the same idiots that were throwing pizza parties.

I guess. I think that there’s elements of that thrash but I think there’s also a political, social bent to the more vital version of it. They were tied to a very specific era that had problems or fears that maybe don’t exist today, like the threat of nuclear war. That’s another thing you have to understand. As someone who grew up in the ’80s, I was afraid that Russia would nuke us one day. That was a legitimate fear that you had as a kid from all the propaganda — not just Rocky IV. This was something that you thought was an inherent possibility. I think the fact that it was so timely and not really stretched to that kind of next level [was important]. Punk and even grind have done so. Think about how relevant Napalm Death is today: how they’ve managed to take the tenets of what they were screaming about in the mid-’80s and develop it. I don’t really know what thrash bands sing about. You talk about this darkness and that’s a less tangible idea. It’s not specific. It can be interpreted in a lot of different ways and mean a lot of different things to somebody, rather than, “Reagan is going to get us all killed.” That’s very specific and that’s very timely. The idea that, “I have this power within me that’s propelling me, a darker force,” that’s more malleable of concept. That’s part of the reason, too. Your theory has some weight in that sense. Maybe thrash was just limited to that.

I may be misquoting but I think Al Jourgensen — to go back really far, talk about someone who needs to make an apology to his fans — once said that he’s never made a good album when there was a Democrat in the White House. He knew all of his Obama era albums would be bad because Bush left and he lost his muse.

Yeah, ‘cause everything’s been fucking perfect for eight years. I appreciate that idea of a specific villain, but that’s just somebody who isn’t that imaginative of a writer.

…

…

I love, love, love the book that was the collection of the Hall of Fames. Are you ever going to collect the rest of them?

Well, there’s 25 in that book. There’s 125 Hall of Fames now. I’ve definitely thought about doing another Hall of Fame book, but I think the format would have to be a little bit different than the original one. While I think it’s cool, it feels sort of incomplete; it feels kind of like repurposed content. I’d want to do something that had a little bit more behind the scenes-ish stuff. You’ve done this for a little while, so you realize that sometimes there’s stories that go along with getting the stories.

Yeah.

An example [of this is] the new issue of Decibel that’s got a To Mega Therion Hall of Fame in it. When we started working on that, the first person we appealed to to see if he had any idea where Dominic Steiner, the bass player who was in Celtic Frost for, like, fucking four months — he only recorded that record and then he was, poof, gone — was, was Tom G. Warrior. Of course, he immediately was like, “No, I do not know and I do not care. He is irrelevant to the history of Celtic Frost. He was there for four months and he was an idiot. Blah, blah, blah. Tom Grumpy Cat Warrior, signing off.” I just thought, “Fine. You say you haven’t talked to this guy in 30 years. What the fuck do you know what he thinks about this? Maybe he was embarrassed at the time but maybe he looks back on this as something he’s really proud of. You don’t know; you haven’t talked to him.” Tom wasn’t saying necessarily, like, “I won’t do an interview if you talk to him.” He was just saying, “I don’t think he’s necessary to do an interview if you want to do this.” You know us. We have our rules for a reason. Sometimes, I don’t remember exactly what that reason is, but what we have these rules where we’re going to talk to everybody or we’re not going to do the piece. So, I was like, “Alright. Hang tight. We’ll try to track him down on our own.” Eventually, we ran into a couple brick walls. I don’t remember how, but Justin Norton, the writer, got in touch with Oly Amberg, who used to play in a rock band called Junk Food with Dominic. Also, Oly was infamously one of the guitarists on Celtic Frost’s Cold Lake. Anyway, we got in touch with him and he was super cool. He was like, “I talk to Dominic every once in a while. I have his wife’s email address, but I haven’t talked to him in a few years. I’ll reach out and I’ll see if we can convince him to do it.” He worked really hard on our behalf to try and say, “Hey, you should do this. This is your opportunity to talk about this record.” Guy was in the band 30 years ago; hasn’t done an interview on Celtic Frost since then. Amazingly, he conceded to do it. Thus was born this piece. You won’t see it anywhere else. I’m underselling that story. I’m sure I can beef it up and make it a little spicier. The idea is that the Hall of Fame book would maybe incorporate some of that stuff. It might be more compelling than, “Here are slightly longer versions of these pieces that you’ve already read.”

Well, I’ve got two completely different responses to that. One is that what I like about that book and what I like about the Hall of Fames as an idea — besides that they adhere to a rigid structure, which I feel is valuable in and of itself — is that it does sort of aspire to be not just this press cycle document but a historical document. Buying that book opened me up to so much stuff that I love. Reading those features every month has opened me up to so much stuff that I love and wouldn’t have checked out otherwise: stuff like Failure. Even if it wasn’t repurposed content, it would still have value as a historical or archival document. But, I see what you’re saying. My other thought is: were you part of the Serial craze?

What is that?

The podcasts?

No.

I’ll send it to you in an email. There was this true crime podcast that was a spin-off of This American Life that aired over the Internet last fall. It became something of a pop culture phenomenon. The New Yorker did cartoons about it; it was that well-known. The interesting thing about it is that it becomes a double story. It’s not just the story of this crime that this reporter is trying to solve. It also tells the story of her running around Baltimore trying to find these people and solve this crime. That’s the secret hook to the damn thing. You wind up caring about her struggle and the struggle of the people she’s covering. So, I think you’re onto something. Maybe the story of trying to find Dominic Steiner is not a story for print; maybe that’s a story for audio.

It might be. This is something that I have found with Decibel, that Decibel has superfans, which I appreciate. They really like when you’re able to kind of lift the veil a little bit and talk about that process of how this all comes together. Being able to do that a little with something like the Hall of Fames where that process is always complicated [would be good]. Even with the simplest ones, there’s always something about it that just makes you fucking facepalm at some point during the month when you’re trying to get something done. All of sudden, “We didn’t know that this one guy hates everybody else. This is going to be that much harder to complete.” That’s all a direct result of having that structure, which is in place for a reason but still complicates things. I do think that it could be interesting. I’m not saying that they need to be, like, crazy 5,000-word fucking pieces about the process of putting it together. But, I do think that something that kind of gives a backstory to the story with a Hall of Fame might make for a little more compelling of a package. You still can get that kind of historical reference book of these albums, but for people who have been subscribing for years and have been reading these things all along, they can feel like they are getting something else in addition to all this content they have already spent some time with. So, I think you have to think about things like that, too. You have to think about time because we don’t have a lot of it. Our tour starts in less than two weeks. I’ve got a book to promote. I’ve got a magazine to do. I’ve got something else that we’re cooking that could be big in the fall of this year coming up. There’s always stuff going on.

…

This article has been edited to properly reflect the name Oly Amberg

…