I'm Listening to Death Metal #9: Gorguts' "Colored Sands" and "Pleiades' Dust"

…

I’ve spent the last seven years, off and on, attempting to put into words what precisely I see in death metal and why it means so much to me. This column is my latest and so far best attempt to enunciate the value of death metal to me, artistically, aesthetically, and emotionally. The following are a set of guided stories loosely centered on certain records and the various relations to them, both inside and outside myself and the records themselves.

…

Gorguts formed in 1989 at the crux of the death metal boom. The genre had been active for only a few years at that time, the big bang records of Seven Churches by Possessed and Scream Bloody Gore by Death having been released only four and two years prior respectively. This was also the year that the seminal Altars of Madness by Morbid Angel, a clear influence on the young Gorguts, would hit shelves. It’s hard not to see why a group of talented young metal musicians would be into the genre: it was at this time too that early tapes by Atheist and Cynic were making the rounds as well as the later more experimental turn thrash was taking, with groups like Coroner and Voivod (a connection which will recur) releasing mind-blowing progressive and experimental records in the underground while Slayer was producing a demonically heavy (relatively) mainstream metal sound. The seeds of second-wave black metal were already in the air with more primitivist groups as well, but those seeds had not yet sprouted.

All in all, for those tapped into the underground, 1989 is a fine year to finally be inspired to pick up the axe and begin writing some incredible death metal.

Gorguts released just a single demo, …And Then Comes Lividity, which caught Roadrunner’s eye and nabbed them a record deal. It’s worth remembering that prior to the general death of mainstream attention to extreme metal that happened in the mid 1990s, and then the commercial success of groups like Slipknot and Nickelback, Roadrunner was known for being one of the best champions of deep-underground extreme metal music, alongside other stalwarts like Metal Blade and Nuclear Blast and Earache. Roadrunner was the initial home of that magical first and slightly-less-magical second run of Mercyful Fate as well as the longtime home of groups like Sepultura and Obituary, as well as handling Scandinavian distribution of the first few Metallica records. They had a remarkable ear at the time not just for cutting edge extreme metal but both great and promising groups, ones that didn’t just drop a wonderful debut and fade away but would then continue to grow over time.

Gorguts turned out, as we know now in the fullness of time, to be one of those groups. Their debut album Considered Dead is even now regarded as a landmark early death metal record, with a full slate of absolutely gross death tunes. Both from the title of this series and the fullness of history regarding Gorguts, I’m not simply bringing up Considered Dead to discuss it alone. In that context, it’s definitely a curious listen, one that shows the band playing it almost entirely straightforwardly, delivering death metal material that wouldn’t be out of place on early Dismember or Obituary albums. The only major departure, and one that is contextually not terribly major at all, is the incorporation of gorgeous and immaculately designed interlocking acoustic guitar passages. These occur only briefly, located primarily on the intro track and the beginning portion of “Waste of Mortality.” It’s a move copped from Metallica, the group who popularized those kinds of passages in an extreme metal context, and thus can’t really be said to be wildly out of left-field given the obscene (and deserved) popularity of Metallica, even if death metal records at the time were much more sparing with those lighter touches.

…

…

Considered Dead, regardless of its very real charms as a solid old-school death metal record, exists in the mind-image primarily as the negative control for Gorguts in specific and, for the context of this article, the seamless scope of ambition itself. Even a casual listen of a single track from the group’s recent material shows how far they took the ideas presented here; Considered Dead acquires a dual identity. First, as a compelling early example of death metal that was actually a fairly popular and influential record on its release ( the greater acclaim the band would receive later in their career notwithstanding), scoring the band a support slot on that now-legendary Cannibal Corpse and Atheist tour bill, and second, as shockingly primitive example of where the group would eventually extend their artistic ambitions.

It was a satisfying shock to listeners in 1993 when Gorguts’ second album The Erosion of Sanity sported a substantially more technical approach. The songs still largely skewed toward traditional death metal sonic spaces, but the riffs were more informed by the frantic and technically demanding spaces thrash metal had moved into in the previous few years. While …And Justice For All is the most obvious record of the style in terms of broad cultural influence both within the extreme metal underground and without, groups like Dark Angel, Tourniquet, Toxik, Watchtower and more were releasing seminal tech-thrash albums and the subgenre was even large enough to be largely responsible for second-wave black metal taking the deliberately simpler primitivist sound it did in reaction.

Gorguts, however, decided to skew hard the other direction, joining fellow bands Suffocation, Death, Pestilence, Atheist, and Cynic in a more progressive and technical direction.

Still, The Erosion of Sanity feels like it is miles away from their later work. There are glimpses, of course, particularly on “Condemned to Obscurity” which opens with a surreal sci-fi synth intro before segueing into the same kinds of extended technique riffing that would come to define later period Gorguts. But by and large, if the group had changed their name between this record and what would come after, if they were two entirely different groups, we would not think necessarily to draw a line. This in turn makes The Erosion of Sanity interesting to situate within the broader context of the band’s work. If Considered Dead was like a caterpillar to a butterfly, then The Erosion of Sanity is like a cracking cocoon, one in which the same constituent parts of its earlier form have been molecularly disassembled but yet still remain, being recombined into the beginnings of some new and seemingly wholly unrelated form. (Side note: One of its tracks “Orphans of Sickness” would later become the title of a short cover EP from Krallice, of whom Colin Marston would eventually join Gorguts).

…

…

Speaking in terms of theory, with one work alone, we have a nest of potentialities but no necessary directionality. We can imagine the inscription of artistic identity as a kind of mapping, one in which key works act as points in this space describing the edge of some unseen object and minor works acting as a kind of halo of curvature, not so much distinct mapped points themselves as they are ways to offer specificity and depth to the points we are given. In this way, in the context of death metal, demos tend less to necessarily signify a proper recording debut by mirroring all of its contents but instead better as objects we can look back to after a release to see which elements remained and which were, at least for that particular artist, the chaff of influence that had to be worked through, embodied, and discarded to get to the guts of the band’s eventual identity. Likewise, the pure power of debuts is precisely their non-directional nature, the way that a singular point on a piece of paper can become anything from the plans for the Eiffel tower to the works of Zdzislaw Beksinski to a haphazard childlike scribble.

It is with a second major work that we now not only have two points of nested potentialities but also the ability to draw a line connecting the two, a line which may have any number of historical wiggles and deformations keeping it from being a perfectly straight line but still, ultimately, a line. From that line, we can begin to ascertain directionality, both in terms of the crass sense of the direction a band’s future works will go but also in a more abstract sense that it begins to better outline the shape of identity. It is important, on some end, for artists, critics and audiences to map the course of a band’s work, but the more important labor is that second form, where by accrued work we begin to understand the core internalities of a group and what ideas and forms they bring to the table, whether wholly new ones or just satisfying executions and methodologies of existing forms.

With their second record, The Erosion of Sanity, Gorguts began an arc that seemed to describe a group of similar inventiveness, curiosity, and ambition as groups like Morbid Angel, Death, and Atheist. But their tale was cut short; due to the popular decline of death metal outside of significantly bigger acts like the aforementioned Morbid Angel and Death, the economics of investing in groups like Gorguts began to make less sense for the company Roadrunner had grown into. They were summarily dropped and, were it not for the unpredictable course of history, that may have been the totality of their tale; one solid debut and one incredible followup, and nothing more.

…

Ambition is, of course, a strange thing to measure. An obvious but necessary point to make is that everyone has ambitions, or at least so close to everyone that (for now) we can assume it to be so. And so as a result talking about groups as “ambitious” can feel crass and reductive in the same manner as referring to “technical death metal” can effectively marginalize the tremendous technical demands of even very run-of-the-mill death metal. Just as playing continuous blast beats at high tempos and shredding along at those same rates isn’t exactly easy even if the time signatures and key changes aren’t that wild, ambition itself is a near-universally shared trait not just in art but in people more generally. We do not, or at least should not, imagine the people we witness on the street and through the window and at work as being devoid of their own ambitions, desiring in part things like stable homes and being valued and loved by their peers but also things like notable success, contributing to the shape of the world as they desire it. And so sometimes we find discussions of groups under the blanket term “ambitious” of being thin at worst or undefined at best.

One of the common poor definitions of ambition is groups that seek to disrupt the status quo either with some brand new ideas (incredibly rare), a new context for an older idea (much more common), or superb execution of existing ideas and contexts (the most common to aim for). And while this certainly counts as a sort of ambition, being that we tend to view the ontological lower limit of ambition as being where desire transcends into the plane of immanence and becomes a driving force, ambition being the active form of the passive desire, it is still itself a relatively shallow one. Or, perhaps “shallow” isn’t the right word here, maybe because that sets up imagistically the same false comparison that the cheaper definition of ambition holds. The issue isn’t depth or height, to which both “shallow” and “ambition” seem to gesture, but that neither of these forms seem to address the internality of what ambition is. It measures only in magnitude and not in transformative power, which is a more useful way of approaching the concept.

A parallel in war imagery would be a nuclear bomb versus a targeted elimination of the single target you were looking for; sure, nuking a city may by definition solve the problem, but if you really are trying to destroy a single flash drive, then perhaps there are better ways to approach things.

This gets at the much more interesting question in art criticism, the “why” and not the “what.” Too often we get caught up on the “what,” saying things like, “Radiohead incorporated electronic elements,” or “Kendrick Lamar wove overarching narrative elements into his rap,” without necessarily interrogating the motivation, the intention, or the resultant real effect this has. This is often the root of the adoration in some circles of very bad progressive music that nearly everyone rightly rolls their eyes at, with notions like long songs, lots of riffs, and weird time signatures alone being the justification for the music rather than whether it assembles to something compelling, and in doing accidentally buries the legitimately great progressive music to those burned out by those shallow defenses of the ambitions of the former. It’s also, ironically, precisely what drives the equally thin and useless notion of striking out pretentiousness, itself the equally poorly defined negative form of ambition, where critics and fans alike internalize a general dislike of ambitions (be they formal, conceptual, thematic, etc.) as somehow missing the point, a stance which likewise privileges the “what” over the “why.”

German author Goethe offered a good and practical way to parse these questions. His critical approach was to table three fundamental critical questions. The notion of those three questions isn’t to replace critical inquiry but instead to act as a stable bedrock for it. The first is a question of identity, determining precisely what the object/idea being criticized or developed is, the second is to ascertain its intended purpose or intended resonances, and the third is to evaluate its success at those endeavors. It’s obvious that this doesn’t replace all other potential critical questions one can employ, but in terms of focusing them on the “why” of an object, the mechanics of its internality as opposed to its bare externality, it offers a strong beginning to criticism. (This ignores, of course, the entire field of critical theory that posits all art as bare, infinitely shallow aesthetic upon which we experience the holography of emotional, experiential and intellectual resonances purely internally, but that space and its dialectical relation to this one will come up in a later installment of this column).

Through this, the question of what constitute more important or even just more interesting ambitions of a work to interrogate becomes easier to answer. You can relegate fairly quickly certain quick aesthetic elements — like for instance whether it’s a concept album, a maximalist novel, minimalist work, etc. — and instead focus on the motivating forces that spurred its generation and the mechanical function those forms provide. But this method of interrogating ambitions doesn’t just work for art but for the breadth of the ambitions of any force whatsoever, be it human or not, political or not, willed or not. It is through this lens that critics develop, say, a set of critical questions for something as specific as Elon Musk’s traffic tunnels and what motivates not just the creation of something addressing traffic in a way that can incorporate the future of electric/smart cars, street safety for pedestrians and bikers, as well as traffic loads and congestion for roads, but also a privately-subsidized tunnel system operated via electronic keys owned wholly by a single operating company. These are questions that mirror as well the motivation for sending one of his own cars to space. It is through this lens as well that the better political critics less taken away by the pure spectacle of most populous-facing political actions interrogate political figures, reading the motives and mechanics for things like stump speeches as opposed to being caught up in the bare, dead aesthetic of the (typically, and knowingly) empty promises.

But even these critical implementations of ways to interrogate the raw ambition of humanity, that will to power Nietzsche delineated from both the Schopenhaueran will to death and the Hegelian dialectical/historical urge, but also to gaze at our own common lives. There is a point in youth when, filled with idealistic dreams, we want to change the world.

…

I wanted to be an inventor as a child, and I’d sketch out dozens and dozens of ideas and demo lots of little objects in my garage. None were all that great, though my notes promised incredible things (the way a child’s often does), and while my tinkerings will reasonably furnished with access to tools and supplies by virtue of a middle class life with lots of random breaking mechanical objects full of goodies for me to extract, I never made anything of note and eventually moved on from this dream. The next dream was, incidentally, to be a writer, something I’ve described previously. But while the externality of these ambitions was different, the guts were the same. I wanted in youth to fundamentally change the world, either by making incredible undersea domes (I was fascinated with sub-sea habitats as a response to global warming and rising tides) or by creating the next great American novel.

As I grew older in my youth, my literary ambitions evolved. I quickly found that I had a taste for poetry, for creative nonfiction, for philosophy, for criticism, and not just for novels and short fiction. My resultant will for myself grew at equal speed; the notion that I should be limited to one genre of fiction or one formal construct of writing felt simple, stupid, small to me, and while I became quickly read on the fundamental difficulties publishers would face marketing the work of a writer who’s body does not have any sense of self-consistency, I found no energy or will to continue from those who set their flags in the sand on one particular patch of literary land to cultivate as there own. My heroes, as vain as this was in ways in retrospect, were those that roamed more freely, be they people like Philip K. Dick or Kurt Vonnegut or Margaret Atwood or the like… people who wrote gargantuan books that internally spanned from psychedelia to literary fiction to memoir to history text to sci-fi and fantasy.

The notion of ideaspace as fundamentally unlimited appealed to me both then and now, and the works that appealed to me tended to be either works that explored some long-forgotten corner of that multidimensional labyrinthine space or else walked the labyrinth itself, swirling among the curves and corridors of the infinite internal space of the thing itself.

And yet this is a self-aggrandizing read of my own taste, one that describes also the strangeness of ambition. Because my ambition certainly was as I described, but my influences, the things I actually dearly loved, were occasionally quite different. There is no one in the modern world who has not loved a dumb TV show, no one who has not loved a cheap popcorn flick, no one who has not enjoyed a lightweight book. And in truth, the people who aim in their ambitions to create the world-altering art of some impossible as-yet unseen future arthouse utopia tend more often than not, we know, to make work more like the latter than the former, to the point that “fake deep” is its own aesthetic marker the same way “psychedelic” is.

We may resist this term as self-denigrating, but what else would we call a show like Westworld, which is baldly idiotic if you take its philosophical questions seriously but nonetheless is enhanced by being even quite dumbly philosophical but applying it to robot cowboys? And in fact by integrating this notion into our broader conceptual image of ambition, that it is but one motivating force that often is self-blind to other contributing forces, we can better understand Black Mirror, a parallel show to Westworld that receives substantially more critical backlash despite having near identical intents and, if we are honest, very similar results. Because ambition, while it declares itself the supreme force, the force which roars past influence and instead achieves a Deleuzian/Nietzschean recurrent singularity of being, is just as synthetic (as in “prone to synthesis”) as anything else.

Which makes it all the more fascinating when, carrying these more complex, subtle, and nuanced understandings of what precisely ambition is and what precisely it does, we witness something actually seem to achieve that first, simpler form of creating something beyond imagination.

…

…

It would be five years between the release of The Erosion of Sanity and Obscura, Gorguts’ seminal third album. In the intervening time, word from the camp would go completely cold to the public, and their lack of appearance on major bills or label rosters made many believe the band was dead. Five years is not altogether too long a period between records, but it is on the outside of what an active band can get away with; for a group that had dropped two records in just about 15 months, it felt certainly like a death sentence.

It is fortunate, then, that the group in truth had not disbanded whatsoever. There are personnel turnovers aplenty, of course, with Luc Lemay being the only member of the band remaining from its previous incarnation when at last the group finally returned, but the material comprising Obscura itself was written fairly shortly after the release of The Erosion of Sanity, largely being written by the end of 1993. The reason for its silence was simple: the music was too strange for labels of the size and musical interest that would provide the right peer group for a band like Gorguts. One can easily imagine an alternate world where Gorguts placed the record on an avant-garde or experimental music label, but that would have shifted the positioning of Gorguts as a group. Something commendable about Lemay’s stewardship of the group is the fact that he never sought to position the group as anything more or less than death metal regardless of how experimentally, progressive, or avant-garde they became. It simply became a hurdle for that period.

Undoubtedly, the five years the band spent jamming these songs together, recording, and re-recording them for demos to send off to labels helped shape them, if not for extending their outre elements then at least by making those movements deeply natural come recording time. The finished product is a masterpiece of death metal, albeit a flawed one, one of the first major examples of death metal work that extended far beyond the conception of the genre to include almost Bartokian levels of elaborated thoughts and forms. The title track features incorporated extended techniques not as flourishes but as components of the riff itself; “Cloud” is a lengthy and pained example of death/doom where the notes seem to be pulled out of the vocals and guitars more by the players being placed on a stretching rack than by traditional playing.

If the previous album was technical death metal in a manner we might understand currently, one that favors things like shifting meters and physically difficult music to play, then Obscura featured music that was conceptually difficult both to conceive and then to consistently execute. It still stands as a landmark of not just what players can do when they woodshed their technique long enough, a trait of musicianship as necessary but boring as wiping one’s ass and washing one’s hands afterward, but also what artists can conceive of given time and ambition.

Obscura is, of course, a record any reader of this column should be familiar with. In fact, there was a temptation when covering this topic to focus on that record instead of the later ones, and admittedly there are good reasons for pursuing that path instead. The most obvious one is that, for many, many people, including band leader Luc Lemay, when asked to name the single record that describes the goal of the band and lays its pure ambitions barest, it is Obscura. This record is to Gorguts what Master of Puppets is to Metallica, Reign in Blood to Slayer, or Sunbather to Deafheaven (for a more modern example). It’s the record through which we view and understand the whole of the group’s work.

To return to the caterpillar metaphor, Obscura would be the butterfly itself… perhaps wet and dewy from its time inside the cocoon and still prone to the changes that come from life in the world, but still at least the final image of the insect.

But Obscura ironically is undermined in its function in that capacity precisely because the band, being one of deep artistic ambitions, did not see it as an end. Their follow-up record From Wisdom To Hate would feature the same concepts as explored in their most outre form on Obscura but re-implemented in the context of the technical death metal framework of The Erosion of Sanity. The album, admittedly, is only very slightly less unapproachable than Obscura, especially for the time period, where approaches to death metal still tended more toward groups like Suffocation than the deep incorporation of extended techniques that Gorguts employed. The lineup once more changed, with only the bassist Steve Cloutier returning. On second guitar was a player named Dan Mongraine, at that time of the relatively young tech-metal band Martyr, who had only just released their second record. Being that they were both Quebecois players of similar intent within heavy metal, he seemed a good fit to Lemay, such a good fit in fact that his playing for Gorguts (along with his own group Martyr) would eventually become grounds for him later joining the seminal prog thrash band Voivod as permanent replacement for Piggy D’Amour.

And if Obscura represented the artistic abiogenesis of Gorguts, the bursting of the life of their ambitious concepts for death metal with little in the way of referents to other groups playing the style at that time, then From Wisdom To Hate was their attempt to forge those concepts into a usable format.

…

…

While we can see clear lineage in later experimental extreme metal bands like Portal and Mitochondrion, as well as Pyrrhon and even Imperial Triumphant with that earlier record, Gorguts was more interested in developing outre ideas and using them within the confines of more traditional death metal. This in many ways ties back to their desire to see Obscura land in the hands of a metal label, eventually being released by Century Media, rather than by an avant-garde record label. There was a desire not to abandon the context of death metal but instead to show people the creative breadths the style could contain. It seems in retrospect to partly be a response to the criticisms leveled at the genre, especially by the late 1990s, by the rise of black metal and then late the rise of nu-metal, of which many groups both cited death metal groups but cited alongside a sense that they were outmoded and no longer modern.

The image of a modernized death metal was, to Lemay, one that had the same breadth and creative richness of contemporary classical music, an influence that was apparent on the earlier records with the acoustic arrangements and with Obscura on its positively Pendereckian approach to extreme metal. But From Wisdom To Hate saw those influences wielded toward ends closer to Stravinsky or the tremendous and rich darkness of the darker pieces by Chopin or the sort, offering a remarkable sense of transparency and breathe to the arrangements where Obscura and the records before sought to suffocate.

Moments such as the opening to “The Quest for Equilibrium,” a symphonic arrangement of synthesized strings, timpanis, and bells, would hint at the later richly contemporary classical vein the group sought as the new contextual basis for their extended technique-enhanced technical and progressive death metal. Worth noting as well is the seamless transition between the synthesized introduction to the song and the slow, dirge-like, sludgy mid-tempo death metal riff paired against inventive drumming that doesn’t rely on the cliche of endless blast beats but instead cuts between more orchestrated sequences, hits, and patterns.

Following the release of From Wisdom To Hate, the group began to tour heavily and saw an uptick in their international and press presence when, unexpectedly, their drummer Steve MacDonald took his own life. Gorguts struggled on, attempting to find adequate permanent replacement, but in 2006 eventually dissolved themselves. And so too, it seemed that the group would melt away, albeit this time with not just two solid albums under their belt but two later gamechangers. It was off of the backs of Obscura and From Wisdom To Hate that the group would develop its cult following; these are the records from which the majority of their influence would shine from. The influence of those two albums cannot be understated; it is nigh-on a guarantee that all of the great experimental death, black, sludge and doom metal that came in the years following were played by those who heard those albums and learned their motives.

…

But one’s ambitions do not merely change in regards to their profession. I’ve spoken before about my mental breakdown and subsequent suicide attempt and total psychic dishevelment and so don’t wish to belabor that point here, but that moment was not only a black hole of my psyche but also of my directionality. Prior to my breakdown, I had a very particular writing style, one that was equal parts surreal, psychedelic, and crass humor and cerebral, overly architectural movements. I was able to write at an incredible pace, sometimes finishing full novelettes in a day. And while publication rates were scattered then, I was still young, between the ages of 16 and 21, and so any publications at all were better than what I was expecting. I had a long-term girlfriend, my first serious partner, with the same loose intent to marry as any high school sweetheart couple that makes it long enough into their college years.

But my family life was disintegrating under the shadow of abuse and neglect turning rancid inside. I had internalized in my toxicity a tremendous amount of parallel toxic thoughts and had become a deeply unwell young man and I wanted to propagate this in my own way.

Then came my meltdown, not in a great rush but in small disintegrations that only became apparent in hindsight. First was the inexplicable silencing of my creative voice. I went from writing constantly, pouring words out onto the page both good and bad, emulating all the styles under the sun I could get my hands on, from Virginia Woolf to T. S. Elliot to Thomas Pynchon and more and more and more, to absolute stark silence. It felt like being closed in a silent room, one where the walls and ceiling have been soundblocked to leave you without any sounds save those inside your own body. In retrospect, this was a sign of deepening depression and anxiety, what with most major mental illnesses kicking into high gear not in youth but in our early 20s. At the time, though, it felt like a collapse, this creative voice that I had decided at a very young age would be my life and livelihood and made a variety of commitments to suddenly disappearing. I felt lost at sea, having given too much and hung too much on its continued presence to easily reconstitute a new direction for life, at least with the lifeskills of someone in their 20s.

On its own, this would have been a minor if upsetting fluctuation. But then my dog died, the pet that had been my partner and stability and only sign of love in a house that slowly ripped itself apart at the seams from alcoholism, neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and the corrosive silence and cheary mask of suburbia, ever the cover to the rot of the workaholic and over-privileged families it holds. Without that lynchpin, things worsened, and soon I found myself unable to see, speak, or think about my family without collapsing into as-yet-unprocessed rage and primal that had over the years finally found its way to the surface. My breakdown, where I spent a week bedridden, shaking and weeping and desperate for sleep in fear of death for sleep and the brief eclipsing moments of first wakefulness were the only moments I had respite from my newly-rediscovered deathconsciousness, made to witness cold and naked and trembling the vastness of the oceanic spans of time and the infinite bounds of space and my utter and undeniable worthlessness in its face.

Following that, my girlfriend left me. I can’t blame her; I was inarguably not a great boyfriend before, the same kind of dumb shithead early twentysomething white dude college kid as anyone else, but was also in the midst of a terrifying breakdown and psychic disintegration. She had her own life, too, a life beyond just me, and one that had its own problems. We stayed friends after; we still call on each other’s birthdays a decade after the fact. But it was just too much for that time then.

All of which amounted to a near-total erasure of the stable ground on which not just my identity but also my futurity was founded. Because the negative component of ambition is it not only defines our future, as in the state we will inhabit someday after the present, but also our futurity itself, as in the sense of direction and comfort we have in that forward motion. Any penny-rate therapist will tell you the common grounding advice to live in the moment, that regret and shame live in the past or reference the past while anxiety and dread live in the future, with the present often unmarked. Focus on the present is functionally a shield against the arrows of the wounds of time, both the oceanic Before and equally oceanic After. We may, in some macro scale, feel tremendous terror contemplating our consciousness before it arose in us, those billions of years before birth, and feel a mirrored terror imagining the unwritten billions of years that will follow with us outside of the world. In micro states, we may relive every unkindness we visited upon another, every selfish act and shithead decision and moment of violence, and we may dread the loss of friends and the loss of our homes and our livelihoods and identities.

But, in the present, unless we are under immediate physical threat, we find those tensions dissolved. You, reading this, are alive, not currently under assault. Certainly you may find yourself in dire position even minutes after, but the precise moments of our pain are far outnumbered by the moments of our safety. When we cut off the aura of threat that covers up the times directly outside of our pain and suffering, we find the vast majority of our days are spent without harm. As I said before, it’s a common grounding technique that any therapist will tell you to help get through panic attacks or moments of distress.

But the downside to it is that we psychologically do not live fully within the moment, nor should we necessarily. Part of the function of the past is to ground our understanding of the world, even something so simple as sense information. Try playing a song, pausing it in the middle for several minutes, then finishing the track. It doesn’t feel the same as playing it all the way through — this is because our brain partly uses the vector of time to synthesize sense information into a coherent image of the world, something we can’t extract with armchair philosophizing and easy therapy advice. We use the past as a vector to understand the present, whether it be something as background noise-level as the model of physics in the world we live or the film we’ve been watching all the way up to remembering whether someone loves or hates us to tell us whether we should trust or fear them.

These relations, of course, become ever more complicated the more nodes we add to this web, as each node relates to nearly if not entirely every other node in the system. In this manner so too do we need the future to understand the present. The fear of death, for example, makes no psychological sense in a purely present-driven ideology, as we are only ever dying for a brief window of time that makes up an infinitesimal portion of our lives, and when we are dead we can’t experience death anyway. However, this tremendous anxiety-inducing fear exists and permeates nearly every aspect of our consciousness, being the driving force for the capitalist’s accumulation of wealth, the patriarch’s control over the bodies and wills of women and non-men, and the racist’s paranoia of displacement and replacement.

One extension of how we need futurity in this way is also our understanding that we are to live, that we have a future. This can be as direct and concrete as the way we view and approach life with a terminal illness versus without (excluding, for the moment, that tremendous doom metal insight that life itself is a fundamental terminal illness) or as abstract, as it was in my case, that we have a future that is not ruins in front of us.

My situation, it turned out, was not nearly as ruinous as it appeared to me at the tender age of 21, years before I would go through extensive therapy and processing programs to being the healing process of everything that came before that breakdown, stretching back into the generational trauma that inflicted itself upon my brother, my parents, my grandparents, and more. Situations such as systemic racism impoverishing whole communities, from schools to homes to businesses, is a more deadly stroke of the blade than what I suffered, as is the way a prison sentence fundamentally destroys the life of the inmate who likely will never be given a chance to re-enter society peacefully whether rehabilitated or not. But the loss of the grounding of futurity and with that the ambitions with which we build and develop our lives is not only measured in the positive, that of opportunities available or unavailable, but also the negative, that of opportunities or life paths we once possessed but now are gone. It is this trauma vector that affects people who undergo divorces, lose their careers, lose a loved one; it is not merely the pain of the loss itself but the knowledge that this loss replicates itself in every moment going forward, knowing you will never speak to your father again, never become the person of importance within your career you desired, never hold those tender moments within your marriage again, etc.

Yet, part of the funniness of both ambition and time, as well as ambitions within the vector space of time, is that they are not merely static objects. Certainly they create static objects in us; even if we don’t share those ambitions ourselves, the notion of writing the Great American Novel or becoming the president is something ingrained in all of us as at least something that can be desired, as well as things like a large and loving family, the respect of our peers, and more.

And the strangeness of time is that, while I write extensively about that one disruptive moment where in the span of about 15 months I went from an optimistic future with a spouse and a career and a loving family to isolation, suicide attempts, addiction, a dead father, and a disrupted family, that was a decade ago now. I’m 30; it was a third of my life away. Time, being not-static, has moved on and I have moved with it. Clearly I have a monthly column now, but I’ve also written and published a novella, novelette, have more fiction brewing; I’ve a loving family and a steady, stable relationship; I am sober and I have a home. The contortions of those earlier years have dissolved into the ether. I hold onto their memory-image because, as I said before, the past indelibly shapes the future and is one of the lenses with which we understand our present circumstances and the shape and mechanics, both physical and emotional, psychological, of the world around us. But it is not the only lens. Futurity and ambition rebuild themselves through the very act of being alive. Even nihilism and the death-urge are ambitions of a sort.

Madness and the violences it inflicts on ourselves and the world around us too are a sort of ambition. This, too, is a means of proving something to myself, watching as seeded ideas take root and splay out like mad vines twisting over the surface of some invisible edifice only I can see, proving in their shape that the invisible shape beneath them is real, exists, is valuable, and not just to me but to others as well. That I can.

…

The classical influence on Lemay’s composition was not an incidental affect picked up to impress metalheads looking for a little extra sophistication in their Satanic headbanging, either.

In the long stretch between The Erosion of Sanity and the release of Obscura, Lemay taught himself the violin and eventually graduated to taking lessons on the instrument for a number of years, inspired partly by the film Amadeus depicting the life of Mozart as well as exploring the more orchestral wing of the music he was exposed to growing up. Part of the extension of this interest in learning classical violin playing was attending classes at a local college, xeroxing copies of string quartets to study the motions between the independent lines. He even briefly studied viola in a collegiate environment for a year.

It was during this waning interest in playing orchestral music himself that he discovered via a nun who worked in the seminary of the college he attended the pleasures of orchestral composition. His brief work with her allowed him to assemble a portfolio of composed pieces, and on their merits, he was admitted to a conservatory to study composition, eventually spending a large portion of his time in the years between From Wisdom To Hate and their follow-up Colored Sands composing and leading orchestral music for string. In interviews since, he’s elaborated on this motivation, citing a fairly astute and (thankfully) universal notion that while we may be hung up on certain aesthetic and identity elements of genre within art, the core component of any work of art is the abstract or material thing you seek to address, with genre being more a synthesis and averaging out of aesthetic choices made in developing, recording and performing that work.

It is no wonder with that outlook that Lemay allowed his studies on the breath and movement of counterpositional lines in string quartet and trio contexts to inform his death metal writing, and offers a direct and clear line of influence to the kinds of extended techniques employed by composers such as Bela Bartok and Krzysztof Penderecki.

In the intervening years between From Wisdom To Hate, Lemay was additionally tasked with procuring a new band. The players he assembled were John Longstreth of technical death metal band Origin as well as both Colin Marston and Kevin Hufnagel of Dysrhythmia. Both groups show clear influence from the work of Gorguts: Origin displaying lessons learned by the venerable elder statesmen of technical and avant-garde death metal more obviously while Dysrhythmia and more broadly the works of Colin Marston as a whole show it more abstractly, seemingly drawn more to the ambitious sweep and collection of sonic concepts of the group rather than just the music itself. Hufnagel’s inclusion with Marston made two things clear: first, that the previous inclusion of guitarist Daniel Mongrain of Martyr who eventually would join Voivod was not a fluke and that this was in fact the exact sort of second guitarist Lemay had in mind the group (a comparison made both by Dysrhthmia’s work as well as Hufnagel’s solo material), and second, that Lemay, on picking up the entirety of Dysrhythmia sans drummer, was clearly aware of their work and found something within it to be compositionally fitting for the space he wanted to explore.

…

…

If From Wisdom To Hate was the first attempt at integrating the kinds of outre experimental and avant-garde sonic concepts Lemay had explored and learned in the process of writing Obscura, then Colored Sands was its maturation.

Backed by those three masterclass musicians, who among their own work had demonstrated their own incredible ability to play deftly composed and orchestrated multi-part music where the related elements do not always have obvious relation to each other on first listen, Lemay was able to stretch significantly deeper into his compositional playbook. Just as the five-year period between the penning of the material for Obscura and its eventual recording undoubtedly aided the group, the ten-year gap between From Wisdom To Hate and Colored Sands where Lemay studied classical composition and wrote and performed several orchestral pieces had clear benefit to the finished project of Colored Sands. His interest in contemporary progressive music had piqued by that point, with avant-garde, progressive, and experimental music having at long last emerged from the shadows of the underground musical world to a place of acclaim and respect again after several decades of being maligned for its pretension.

Groups like Opeth and Porcupine Tree offered points of comparison for Lemay in terms of executing a fusion of counterpositional orchestral movement within a metal context without it sounding like a tacked on element or a cheesy backdrop of sawing strings against average death metal like some other symphonic death metal groups out there. The resulting album, a loose concept record chronicling the history of Tibet bisected with a string quartet piece composed by Lemay representing the Battle of Chamdo where Tibet lost its sovereignty to the invading Chinese armies, is a masterpiece.

Many incredible metal albums dropped in 2012 and two of them, Carcass’ Surgical Steel (itself a brilliant masterclass comeback record) and Deafheaven’s Sunbather, each received substantially more acclaim than this one. But while Surgical Steel was a sign that after nearly two decades away in bands that sounded wildly different, Carcass could still deliver a record that not only sat comfortably next to albums like Necroticism and Heartwork but felt clearly superior as well. Deafheaven’s breakthrough proved that extreme metal not only could resonate with wider audiences but also perfected a whole new model for experimental black metal to pursue, Colored Sands was simply better than both. It was not a radical reinvention of the band’s sonic concept; the points had become lines already and, especially based off of the two records prior, the conceptual image of Gorguts’ work had become clear.

What Colored Sands was instead was a band perfecting itself, offering lengthy complex sweeps of gorgeously orchestrated music that just so happened to be death metal. There is a deftness to its beauty, the songs conjuring vast sound worlds to inhabit replete with mandalas and prayer beads and the sheer and unforgiving cliffs of severe mountains. It’s ambitions stretch beyond the shores of death metal, though it is, as any Gorguts album is, and as any Lemay has ever penned have been, clearly death metal. It is a deep breath of orchestral ambitions within the context of death metal, one that doesn’t implement strings as a hokey gimmick to prop up middling riffs but a compositional influence that shapes the way the songs ebb and flow internally and against themselves as a loose song suite about the history of a people.

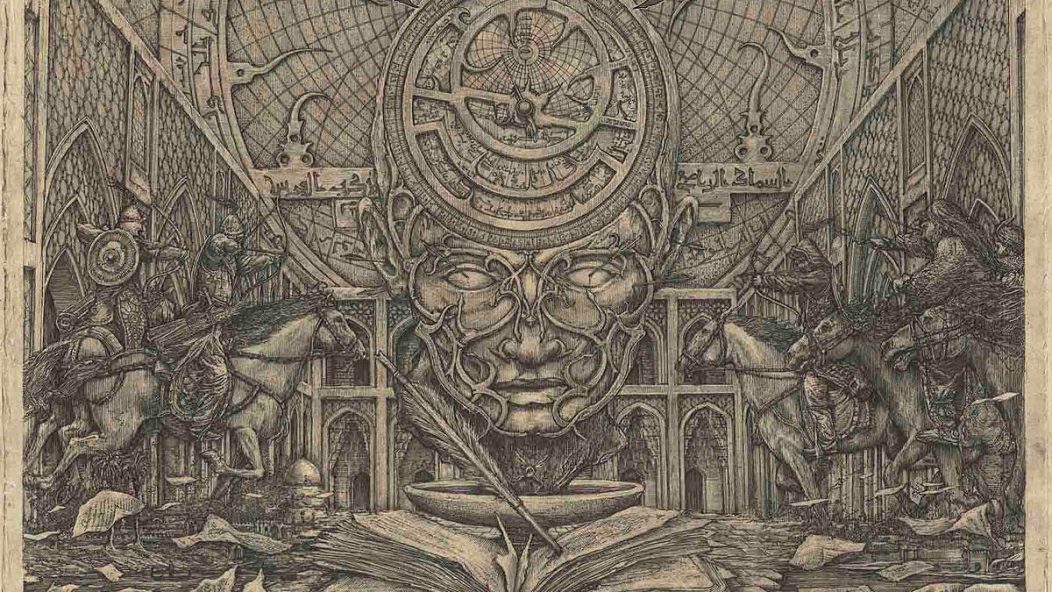

It was fitting, then, that Lemay would push things to the only clearly remaining place left, following up Colored Sands four years later with a gargantuan 33-minute composition called Pleiades’ Dust. Where the previous record played as a suite of related music circling a singular theme, four death metal tracks on either side of a stern and violent orchestral piece in the middle, Pleiades’ Dust was a monolithic entity, a song neither divided into easily indexable tracks nor sharply delineated movements. It is everything Colored Sands is but simply more; a grander compositional scale, a more sensitive instrumentation, both heavier riffs and a more ambitious image for them to explore, devoting the album to the tale of 300 years of the Grand Library of Baghdad from the creation of algebra in its walls to its fall at the hands of invading Mongol armies.

…

…

The piece is neither orchestral music that employs death metal instrumentation nor death metal with orchestral aspirations but a full synthesis of both, demonstrating the fundamental power of death metal to contain and properly execute ambitious concepts of such scale in full fidelity. Pleiades’ Dust is not simply the group’s greatest achievement in their history; it is one of the finest compositions of the 21st Century and one of the finest records in the history of heavy metal.

This is, as of now, where Gorguts’ story stops. They are progressive in the original sense of the word, contributing new ideas and fruitful and eye-opening new syntheses of sonic ideas and spaces, ones that don’t cheapen the constituent elements or reduce them to caricatures of themselves but in full respect enables them to have a more complete and fruitful dialectical relation to one another. It is easy to hear terms like “progressive” or “avant-garde” or “technical” in regards to death metal, or music in general, and scoff, and this is not without reason; there are a great deal of groups who ape the more crass and surface-level elements of those tags and ignore the deeper, more subtle, and ultimately ambitious work of integration.

Gorguts is not those bands. They are one of the crown jewels of death metal. And this is largely due to how they wield and contain ambition as a creative force. It is a fluid and organic element for Luc Lemay and Gorguts, one compelled by childlike wonder and innocent and sincere fascination with sound wielded by a mature and studied hand toward synthetic fusions and approaches and concepts that are designed to intrigue and dazzle us. Ambition can, of course, skew toward more mundane things and are no worse for it; we need not only groups of great original vision in the ecosystem of art but those also with the ambition to perfect and explore those visions already attained.

Groups like Gorguts teach us not to fear or deride things like ambition, not to keep it at arms-length as an obstacle to more sincere and heartfelt work. Rather, it is to acknowledge even that urge toward sincerity and honesty in art is an ambition. Lean into the transformative power of those forces.

…

Langdon Hickman is listening to death metal. Here are the prior installments of his column:

I’m Listening to Death Metal #1: Opeth

I’m Listening to Death Metal #2: Atheist

I’m Listening to Death Metal #3: Ulcerate

I’m Listening to Death Metal #4: Gojira

I’m Listening to Death Metal #5: Tribulation

I’m Listening to Death Metal #6: Morbus Chron

I’m Listening to Death Metal #7: Pissgrave

I’m Listening to Death Metal #8: Morbid Angel

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch..

…