I’m Listening to Death Metal #7: Pissgrave's "Posthumous Humiliation"

…

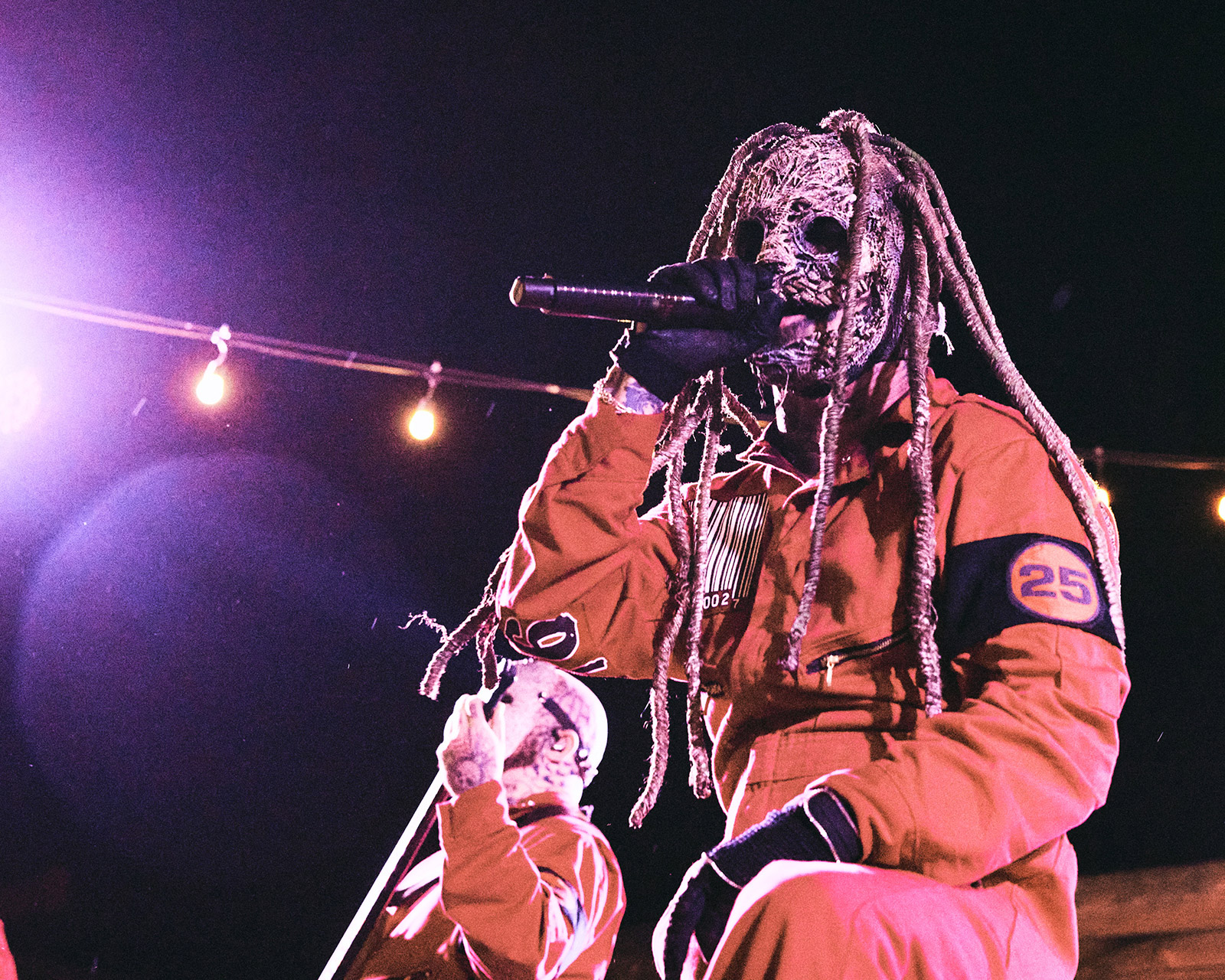

Earlier in 2019, Pissgrave released the most complexly and productively controversial metal album of the year so far called Posthumous Humiliation.

I say “productively” as a means to mark it from non-productive controversy; someone outing themselves as a bigot or abuser is only productive insofar as it allows decent listeners to drop that work, at least when the situation is simple enough. Besides, nazis are increasingly finding they have no place in extreme metal, so while those conditions may be controversial, they don’t produce anything new for the broader metal world. I say “complexly” as well because, unlike instances of immediate and clear malfeasance on the part of a performer, the issue with Pissgrave’s newest album provided a number of useful comments on the central issue at hand, none of which seemed to contradict each other as much as revolve around the same center, like facets of a gem.

Granted, the relatively conjoined center of these varied views was harder to see given the emotional pitch of the controversy itself: the use of the image of real mutilated human remains for the cover art.

Posthumous Humiliation was not their first record to feature pictures of real human remains. Their debut album Suicide Euphoria was adorned with a rather gruesome cover of a body seemingly half-melted by strong acid in a bathtub, the body turned to a vomitous sludge. At the time of that record’s release, it was a shock, but in a broadly positive way, at least for the band; for the first time in a while, a style of art that prides itself on extremity was legitimately shocked, and that shock transferred to listens. Somewhere between the release of Suicide Euphoria and Posthumous Humiliation, however, the gimmick seemed to turn from catching to disgusting, turning off public opinion even among those who listen to extreme music about extreme deeds.

The primary question was one of tastefulness, a question that on its surface seems absurd to invoke within metal broadly and death metal specifically. After all, death metal is the genre of Cannibal Corpse, a beloved and legendary group not exactly known for being the most decent when it comes to respectful imagery, be it visual or lyrical. But then again, Cannibal Corpse never used real photos of real dead bodies before. The terrain felt, if not quite new, then clearly inadequately explored.

And so the controversy, something that is validly and clearly controversial, began to reveal productive snarls and curls and knots within itself.

…

…

The issue, to cut to the core of things, is one of defining “good taste” and then finding its application within heavy metal. This is tricky, obviously; the history of heavy metal, even when only considering the relatively uncontroversial bits, still includes a tremendous amount of depictions of violence both historically real and imagined, realistic and fantastical, autobiographical and desired. Metal is largely fixated on the axis of power and the various relations that arise within that, from supplication and surrender to awe and majesty to domination and violence and fear and hate, and on and on. And because metal is made by real people with real histories, it sometimes is a vehicle for real stories of their own suffering or the suffering of those in their lives, or the desire for those that have hurt the artists to suffer, etc. It is a bound relationship between trauma and metal as a result; there is plenty of metal that does not deal with trauma, but the central topics of heavy metal broadly make it inevitable that trauma, real trauma, the trauma of the living and the dead, will make its way into the art.

I can’t speak about this topic, of course, either generally or about Pissgrave specifically, without referring to my own history of physical and psychological abuse. I have nerve damage that affects the right side of my face as a result of traumatic abuse, non-major and purely cosmetic issues of control of my lips and my eyes and my cheeks and my neck. I can speak directly to the fact that I seek metal and find it appealing partly because it so directly deals with those aspects of my history, both in literal terms at times and then flowering out into the fantasy of bodily restoration, violence against those that have wronged me, or even sick and doomy fixations on the death and decay of my own body. Metal, at least for me, is partly a space where I pursue potentially problematic elements that on some level I psychological desire, art about the destruction and desecration of my own body, art that I consent to allow to trigger me so that I can re-immerse myself in those real and profound pains at my discretion.

In this vector, I did not find the choice of cover for Pissgrave’s latest record particularly galling. It is a difficult image to view, certainly, and when I listen to the album I use a copy with the replaced black artwork. But in terms of choosing an image that, to me, revealed death as something real and terribly physical, not the fantastical image we sometimes create and promote within spaces of extreme art be they horror or punk or metal, was a powerful choice. The sexiness of death and sick joy of art relating to it is challenged by real images of real bodies; it is hard to look back at certain songs or stories or films as acceptable under the lens of the reality of death. I don’t think this is what Pissgrave were thinking about when they selected the image, granted, but I also don’t think artistic intent is all that useful. Our social and psychological responses are not and should not be directly guided by the artist, even if that information is exciting and helpful for navigating certain corridors. Art, or at least the experience of art, lives inside of the audience of the art and in the social aspect of that audience.

Or at least partly. This is one of the complications of the Pissgrave issue. Art may be largely determined by an audience member alone, where the themes of a film or a novel or a record are dependent more on the experience of the work of art than its substance, driven more by phenomenology than ontology, but the ghost of the author and their intent lingers. It’s hard to shake the idea that Pissgrave were merely being provocateurs. In light of that notion, even if depictions of real death may challenge the easy fantasy of art about the topic, can we ascribe those values to this specific instance? And yet even this notion does not dislodge the fact that the image is only controversial because in fact we do mark something specifically troubling about real death, about images of real dead bodies, about the notion of consent to the bodies of the dead and their depictions after death.

…

A few things became apparent monitoring the responses to the album art. First was that almost but not quite everyone was in agreement on the notion of the image being shocking and gruesome and that the usage of a real image of a real dead body marked something, even if the specifics of what was being marked differed from person to person. Second was that this struck at some fundamental question about tastefulness in metal very broadly but also an equally specific question about death metal and black metal. After all, while the image was gruesome in a very extreme and immediately obvious way, it lived in the same aesthetic body as the covers of Cannibal Corpse, which are often so violent as to be banned from entire countries and necessitate alternate slipcases for sale in some regions. Likewise, Mayhem famously featured an image of the dead body of their former frontman Dead taken by a band member at the scene of his suicide. Other images abound; the critique of the often misogynistic tint that death metal, slam, deathcore, and grind bands can employ has been a recurrent critique in the worlds of extreme music; likewise, somehow the notion of NSBM being a real and continuing genre space within extreme music feels relevant as well in terms of greatly pushing questions of tastefulness into clear and obvious unacceptable places.

What we can do with this scattering of data points is begin to draw a map of tastefulness. There are grey areas, certainly, but we can map certain things as lying well within the bounds of the untasteful and others as laying within the tasteful. So, for instance, many find the image of Dead’s body on that famous Mayhem bootleg to be both abjectly disgusting but terribly fitting, given the directionality of the music. Still, it is uncommon to see people champion that release and the reasons for that trepidation come from the same space, that being the image of a very real dead body and one that specifically died of something as universally tragic as suicide instead of the darkness of accidental death. Likewise, Cannibal Corpse themselves seem to have gotten a memo regarding the only major issues extreme music fans had with their covers and over time toned down the misogynistic implications and depictions of their art, erring for increasingly fantastical hyperviolence that takes a superhuman pitch that no longer feels directly relevant and applicable to real people and real bodies, thus freeing them of the burden of being answerable to depictions of real violence.

We can even include in this map certain grind or crust bands that use images of real dead bodies that were killed by political violence; these depictions seem to hinge upon political commentary and not mere gawking at dead bodies and so have a clear and potentially triggering darkness to them but also a clear justification.

Unfortunately, with this mapping, we don’t arrive at a position that seems particularly kind to Pissgrave. The only commentary on the image from the band who was noticeably silent on the issue was the album title, Posthumous Humiliation. While there is an argument to be made that the rim of ironic darkness around this paints a picture more of rage and disgust toward the image, it is a tenuous one, one driven by the phenomenology of those words and that image being put together rather than one that feels easily justifiable as the intent of the band. This is frustrating in a certain way as well; this was after all the near universal reaction to the image, and a mere nudge from the band saying something to the effect of, “We wanted to confront listeners with real and unvarnished death and to restore the anger and disgust that comes from witnessing,” would have potentially moved the dial for them toward more sympathetic space.

But there was no such statement; only silence.

…

As you can probably tell, it’s easy to turn the wheel on this particular issue over and over again without a feeling of any real progress. The image is clearly shit-stirring by a death metal band, but it triggers discussions in a world that is increasingly bombarded with thoughts, news, and images of dead bodies who die for increasingly obvious political reasons. Between racism, queerphobia, misogyny, the authoritarian use of police to control the working class and all marginalized peoples, and the imperial wars of major powers across the globe, we are becoming ever more aware of the deeply political nature of death. Every person that dies of cancer in a hospital ward is someone universal healthcare could have saved; every dead homeless person is someone housing programs could have spared; every person killed by police is someone intersectional reform could have kept alive, and on and on and on.

My father got sick one day from a combination of issues stemming from his alcoholism, which in turn was rooted in PTSD from an imperial war he joined when he was too young to understand what would happen and the abjectly miserable health programs waiting for him when he got home to reintegrate those experiences. He did not get better; over the course of ten years, his health wavered, my family was driven to the brink of bankruptcy, and still he died of a preventable heart attack. As a result of his death and the financial burden of his care, my mother was buried beneath debt and had to return to work after previously being retired. The deaths in your own life are likewise likely marked by the political even if just in minor ways, and we are all becoming more aware of these inflections.

Death metal unfortunately comes from an era where it seems in retrospect there was an amount of callousness to real death. This was perhaps an issue of depiction and reportage, where the mass media of the time did a poor job, whether deliberately or indeliberately, with conveying the deeply political nature of all deaths and the harshness of the reality of death. In the hospital, I touched my father’s dead body, which lay prostrate on the hospital bed. He had not died in bed; instead, his heart attack came, of all places, on the toilet, his body lurching up from the seat to press the alert button just before he collapsed dead on the floor. The nurses then dragged his body to the bed where they administered CPR for almost an hour before declaring him dead. When we arrived, his mouth was agape like a silenced scream, his eyes pulled closed by a nurse’s fingers. His skin was cold to the touch, like he was made of stone, but it was still soft like human flesh. That is real death, colder and quieter than what death metal deals in.

A silent, poorly lit hospital room, the beeps and bloops of the equipment plugged into the walls now silent, everyone scared to speak because that might somehow validate the reality of the moment and make all of us collective realize it is not a horrible dream and we will not be waking up.

It is perhaps from this experience that I invested in that Pissgrave cover the power of demystifying death to people. We treat it sometimes as cliche, something cheap and easy to invoke in art, but I promise you that anyone who was lost a close friend or an immediate family member or a lover or a child has a very immediate recall of the power of death. It is something that, once reinvested with that magisterial darkness, never finds itself exhaustible again. And so I suppose on some sick level the fact that people were so disgusted by the cover pleased me; at last, real death had power again, had the capability to provide that existential shock to people, like they pressed their hand against a busted battery and received a stopped heart for their troubles.

I think often, in obsessive cyclical memory, about what would have happened had my suicide attempt gone off without a hitch, if I’d found the gun, if I had just a little more klonopin in the bottle before I downed it with a handle of tequila, if all the little providences and perditions and aligned themselves and I had terminated my own life; it is a PTSD cycle, one I find myself tumbling back into repeatedly and without warning. I then think of death as cliche and so universal that we can hear of a real human dying and know the pain of their family and not blink. It makes me want to scream. So, on some level, the despair toward that real death was darkly pleasing to me.

But on that level it feels as well critically untenable. That is a deeply personal experience, too deep, and feels irresponsible to stake a broader critical position on that. Besides, there must be some other way to produce such an evocation, one that involves both the consent of the audience to be entered into that darkness and also a framing by the artist about the intent of that darkness. This is, if anything, one of the more pleasing things about the tendency of black metal artists to release pretentious manifestos about their work: they take a certain set of critical questions away and explicitly frame the directionality of their work, allowing us to judge it as successful or unsuccessful at its aims without the lingering questions of something like Pissgrave.

…

…

But, again, they likely aren’t lingering questions. The biggest issue raised regarding the cover was that we don’t know whether the person who died consented to an image of their real dead body being used to sell records. In issues of the more explicitly political deaths, it is easy to understand their usage, and even in well-framed usages of such images we can raise the question but ultimately understand the statement being made. Pissgrave seemed not to be making any statement other than, “Hey, here’s a dead body.” It feels blatantly obvious that the usage of effectively a random person’s corpse to sell your records in that way is wrong, requiring some additional effort or framing or consent given by either the dead or their family.

If I am honest, however, I cannot disentangle my own bitterness towards the dilution of death, the mysteries of death, that tremendum that lingers beyond the veil of the neural death of our snarled rootball brains. The more I sat and pondered its tastefulness and the question of broader tastefulness, the more my own perceptive lens became clear to me, that my own lived experiences have rendered me incapable of giving an honest appraisal of the issue.

Pissgrave made the right call switching the album cover most available to an all-black one, the title and logo of the band in white. It removes this question, which seemed both unanswerable and immediately negatively answerable, and leaves only the record itself, which is a powerful and tremendously grim death metal record. It sonically answers questions regarding the cover, feeling stern, stoic, faces locked in grimaces. Posthumous Humiliation sonically does not seem to delight in death — instead tortured by it — to view death itself as the humiliation, that we all look stupid and garish in death, robbed eternally of dignity.

The closing track, with its ugly harmonized guitars, feels like a tattered flag waving in the wind above a landfill of human bodies. There is nothing but anger on the record, stern inward anger toward forces that cannot and will not change. The cover may have been an apt depiction of the sounds within, but it was also a distraction. Unfortunately, the group dug a grave for themselves, and I doubt the record will be known to many as anything other than “the one with the fucked-up cover.”

It is a condition the group made for themselves.

…

This is, whether fortunately or unfortunately, an inherent risk with extreme music. All experience and imagination deserves art; the experiences and imaginings themselves self-justify the existence of art depicting and engaging with them. However, the existence of art does not then self-justify an audience. Audiences, unless you spring your art on unsuspecting masses, are made up of those who consent, and one of the barriers to consent is that of tastefulness. On a personal level, I both need and desire art more extreme than most to dig out and destroy some sick thing inside of me. Not all people who have experiences parallel to my own need the same kind of art to engage those spaces, turn those wheels and expel those demons; the necessities are caused by internal wheels that turn in ways that we don’t yet have a full and totally psychological understanding of.

Extreme art, just like subtle art or humorous art or surreal art or contemporary realist art and more, is a vector of expression that cannot presume superiority to other forms, because ultimately it serves different audiences and different desires.

However, there is a unique element to extreme and transgressive art that those other spaces don’t necessarily share. We could imagine a deeply political work, regardless of that political direction, becoming a lightning rod; politics, after all, is a deeply divisive and deeply charged topic, and we wouldn’t expect adults who make art to be so naive as to think bold proclamations in that space would go without reaction, both positive and negative. Likewise for extreme and transgressive art, it is not that art that transgresses typical bounds of taste or extremity is inherently invalid as much as we must anticipate that there will be rejection and reaction to it. After all, this is a large part of what marks the art as extreme and transgressive and a large part of what prompts its creation; in short, the very fact that it transgresses bounds of taste is an intrinsic part, which provides the only intellectual justification for otherwise just being a shitstarter.

As a result of this, transgressive art is predicated at least in part on its potential to be pilloried, to have the artists who make it be declared tasteless and regressive, and to face social persecution for untasteful work. An artist who wants to simultaneously make transgressive/extreme art and not experience this pillory, like comics who flagrantly flaunt slurs and bigoted comments, are cowards. There is no other interpretation available; the only artful component of transgression is making us violently reconsider boundaries we assume to be rigid; wanting to avoid the violence of that consideration and still make the art means at some point you just get off on being gross without being in any way artful or productive. The rejection Pissgrave faced must at some point be embraced by the group, or at least future acts such as this avoided, otherwise it paints them as precisely the kinds of infantile reactionaries the more negative responses to their album art paint themselves as.

I don’t intend this column to be a definitive statement on the tastefulness of the group as much as a set of general and robust thoughts on the nature of tastefulness and tastelessness using Pissgrave as a keen and potent current example. There are other bands who merely employ bigots and make hateful art; these groups provide not even an arguable disruption of the boundaries of tastefulness, as I strongly feel bigotry in its forms has no place in society. Likewise, there are many more groups that stay safely within those bounds. The ambiguity and lack of comment from the group themselves lends Posthumous Humiliation — an otherwise strong and potent death metal record that sonically seems to verify the notions of the abrasion of real death versus fantastical depictions of it — an indefinable quality that in turn lends the controversy around it to be a much more productive dive into how we define tasteful challenges to tastefulness itself in extreme art.

Because we cannot kid ourselves. Extreme music in general is predicated on things that challenge traditional good taste, be they gore, Satan, open descriptions of mental illness and suicidality, physical violence, and more. The alignment of extreme art and horror is as old as both genres. The notion of challenging tastefulness, or at least in making art that raises the question, is an intrinsic quality of the space as a whole. But likewise as adults we understand intuitively that this is not carte blanche to make or do whatever we so please, at least not without repercussions, even if they are a quiet disavowal. Burzum is an example of a group most contemporary metalheads have simply and quietly disposed of, regardless of the quality of the records, because the artist simply passed irreparable beyond a veil of good taste. Cannibal Corpse is a good example of a group that sometimes slid over the line but have over time found a space that both challenges tastefulness without itself being so misogynistic that it answers its own question in the negative.

Navigating this question is something we as audience to and critics of extreme art must become comfortable with. Art deserves to be created and exist by itself, without outside justification necessary, but that does not mean we must become a party to it as audience, critic, and consumer if we feel it violates these tenets, is not productive or compelling, and is merely devoid of taste.

…

Langdon Hickman is listening to death metal. Here are the prior installments of his column:

I’m Listening to Death Metal #1: Opeth

I’m Listening to Death Metal #2: Atheist

I’m Listening to Death Metal #3: Ulcerate

I’m Listening to Death Metal #4: Gojira

I’m Listening to Death Metal #5: Tribulation

I’m Listening to Death Metal #6: Morbus Chron

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon; check out Invisible Oranges merchandise on Awesome Distro.

…