I’m Listening to Death Metal #6: Morbus Chron's "Sweven"

…

I have the same methodology for achieving sleep, whether for napping or laying down at the end of a long day to finally rest for a few hours. I take my phone and find a record; any record will do, and often I find myself sleeping to death metal, black metal, industrial, prog, or other more clattering and dissonant things than would be typical for restful sleep, but I am not opposed to the gentle tinkling of a piano and yawning sweep of a violin sometimes either. I set the volume decently high when I am alone, sometimes maxing it out, but more often these days I let set things to around half volume to not totally rattle my partner. I tuck my phone half below my pillow, speaker pointed outward so it roars below my blanket, making an adjustable cocoon of sleep. I close my eyes. I fixate on the music, placing myself into as deep a physical comfort as I can, silencing thought, allowing in only the music. Without fail, within a handful of songs I am asleep, no matter my level of tiredness beforehand.

This has gotten me through noisy flights, boring waits in airports, long stretches of highway when I wasn’t driving, and the tedium between major events. If and when it has failed me, it was almost always due to some severe external circumstance, be it the rack-ack-ack-ing of construction equipment outside my window breaking up concrete and asphalt or the strangulating vine of a panic attack reaching up and around my throat, my chest, my eyes. But, for the most part, it has been successful.

This happens to be a slightly modified version of a technique my mother taught me when I was very little. I didn’t sleep well as a child, taking hours to fall asleep and even then sometimes waking with a jolt only an hour or two later, fully awake mentally yet physically exhausted. As a result, I would often stay up two or three days in a row, making myself as pathetically exhausted as I possibly could, until I was literally dragging my limpening body across the floor and up the stairs into my bedroom where I would collapse on my bed (or just as often on the lush comfort of the carpeted floor). My mother, as it turned out, dealt with the same issue, having been a night owl earlier in life before professionalism caught up with her and waking up at 5:00 or 6:00 a.m. became the norm. The method she used to cope with this change was one she had to figure out on her own, it being the late 1970s and good books on sleep — ones not filled with New Age recursive bullshit — were difficult to come by.

She would lay down in supine position, eyes closed, focusing her attention on her feet. She would focus and shift slowly until they felt at the peak of rest, lightly tingling in anticipation of sleep. Her focus would then shift up to her calves until they too capitulated to the desire. She would then move on to her thighs, her hips, her stomach, her hands, arms, chest, neck, head, until at last she would find herself subsumed in sleep.

As it turns out, a side effect of this methodology that my mother did not see fit to share with me at the time involved the propensity toward lucid dreaming. Following the adoption of the method, which would guide my efforts toward sleep for the remainder of my childhood (or at least until I was able to get a boombox for my room), I saw a radical uptick in the lucidity of my dreams, both remembering the events of the dreams much more clearly and for much longer after waking as well as having more autonomous control over my body within the dream realm. I’m not sure if all brains are like this, but mine didn’t precisely allow me total freedom within that space: things still more or less obeyed typical rules of behavior and physics, or at least closer than they were farther apart, I couldn’t just phase through walls and I couldn’t fly at will or just fire off bolts of energy, nor could I easily command the behaviors of others. It was, if I had to take a guess, a remnant of the internalization of the expectations of the world, that when we drop a ball it falls to the earth or when we twist a rubber band it stores this potential energy and whips itself back to its original shape using that same energy.

My brain, I suppose, refused to let some of these go, and so to transcend beyond them within the realm of dream (for what other purpose would we be interested in lucid dreaming?), I had to trick my brain into accepting the outcomes that I wanted. Once, this meant an imaginary symposium within the walls of my mind, constructing an alternative set of metaphysics for objects to obey. On another instance, I met Lord Krishna beneath a tree under which he was enjoying figs and playing his flute, and in a moment of playfulness, he challenged me to a footrace, and Krishna, being ever the loving trickster, flew feet-first in reclining position, easily outpacing me. His payment to me being a good sport about my loss was to teach me how to fly in dreams as he did in the race, feet-first and in a relaxed position and with mercurial speed.

I am not a Hindu, so I do not know why my mind precisely chose to manifest Lord Krishna as the avatar that would teach me to fly, but that is what occurred.

This was, by and large, a vast improvement on the previous state of dream in which I had been subjected to. But despite lacking proper lucidity in-dream prior to my mother’s corrections of my method of sleep, I still found myself shocked into the dreadful states of hypnagogia, waking dream, and sleep paralysis. A recurring nightmare I suffered as a child was that of a haggard witch dressed in tattered blacks and with a cap and shawl made of lingering shadow sitting at the foot of my bed, doddering and laughing to herself, occasionally turning her head to show me the evil glint of her terrible eye, which would flash between cataracts and a dreadful, youthful clarity and precision. As I grew older, the witch was replaced by a sarcophagus that lay within the walls of my distant closet, ever the domain of evil in the dreams of children. Within that dread tomb slept an eyeless alligator that walked upright like a man. Its face was sewn over and over in crooked lines; it would stalk from its stone tomb to the foot of my bed, where it would lay its hands on the frame and glare down at me from above. Older still, this creature would morph into the darkling beauty of satan, tempting my christian heart with nightly apparitions promising me power and mysteries should I revoke the love of my god.

These sleep terrors were of a marked terrifying tenor, their images haunting me in waking and keeping me trembling in daylight at the thought of providing myself back up to their darknesses in the coming night, but a subtler and more pervasive terror were the hypnagogic fits. Waking dreamstates are a strange thing to experience, closely related to sleep paralysis as a sleep disorder but functionally its inverse. In sleep paralysis, typically the cause is some kind of physical issue resulting in the body quickly waking you, whether some kind of apnea or difficulty breathing; the brain, however, in waking too quickly, has insufficient time to divest itself of the neurochemical blockers allowing sleep to take place, hence providing the same slurred dream logic and physical paralysis that marks traditional sleep while our senses kick back into alert before anything else. The result involves real visions and sensations of what amount to manifestations from our subconscious trying to figure out what external threat is causing the physical issue that caused it to wake. Hypnogogia works in the opposite direction, the brain shunting the same chemical blockers that cause tiredness, uselessness of limbs, and eventually the dark depths of sleep; it does this out of order, so we may begin effectively to see dream apparitions appearing before us moving in strange ways, or words and sentences we utter may slip and stutter and fall in weird orders.

These moments tend to come from disordered sleep too, albeit ones of either narcolepsy or hyperextended sleep/wake cycles, leading the brain to desperately attempt to balance the conscious mind continually requesting the brain stay awake while the physical body and thus other elements of the brain demand it rest, creating this hybrid compromise state.

In my fits of waking dream, I would see ghosts dancing through the walls, speaking my name, laughing from beyond corners. I could see their eyes and their clothes, could describe to you precisely what the wore and how they acted. I gave such descriptions to my mother and father numerous times, to such levels of detail that they sometimes became visibly rattled. Thankfully, the biggest tell of the origin of these startlingly clear visions of ghosts was that the house was not only new but brand new, with my family having stayed in a Holiday Inn for a short period as the house finished being constructed; this indicated quite clearly (even for those that believe in ghosts) that what was happening was something else, something from within the overactive mind of a child with as-yet undiagnosed autism and also a predisposition toward both mental illness and disordered sleep inherited from both parents.

However, reality has little bearing on the world of dreams save for as fertile bedding and little luminous liminal seed material; having sprouted, these phantasias that danced before me would not be quieted, with images of wild horses running through the walls and minotaurs in the basement and pale faces with long hands pressing themselves against the window panes of the house that lived in my waking dreams. Dreams do not bend to rationality, at least not typically, and they reject the notion that that which is not real should not hold sway over that which is.

Dreams are a dark and trembling hand reaching out from beyond the walls of reality, pressing hard enough to bend the shape of the world inside.

…

…

Morbus Chron began their life in 2007 as a somewhat average death metal band. They are Swedish, of course, as much great death metal is, and their Swedish death metal heritage is readily apparent on their debut demo Splendour of Disease. The songs are not bad, but they are also not necessarily good. Unlike a group like Repugnant, which was bristling with so many future top-shelf songwriters that it was destined to dissolve, Morbus Chron felt at first like a group of also-rans. Their material filled a role, and it was not hard to imagine them packing a bill on the bottom end for one of the underground’s typical lengthier extreme metal shows, where as many local bands as possible start playing close to noon and perform a makeshift local metal festival in the lead-up to a touring package’s show later that night. Their followup Creepy Creeping Creeps EP did little to dispel this sense of them being role-players, satisfying injection of tongue-in-cheek humor aside.

This is what made their debut full-length Sleepers in the Rift so startling. It doesn’t represent a modal shift for the group as much as a sharpening, harking back less to the sounds of early to mid-1990s Swedish death metal bands and instead to the quintessential Florida Morrisound death metal tonality made popular by bands like Death, Morbid Angel, and early Cannibal Corpse. Morbus Chron revealed a tendency toward looser songwriting than their Swedish peers, which often tightened up their playing with the stiffness of hardcore as well as a dash of the straight-ahead rock-‘n’-roll of groups like AC/DC. On Sleepers in the Rift, Morbus Chron do not so much as delve deep into the avant-garde as use its uncontoured edges as a slight spice to their goofier, more psychedelic, and more fun loose-limbed death metal, calling to mind at times what perhaps the band Atheist may have sounded like before they went whole-hog on the whole prog death thing. The vocals sway wildly from deep, nasty growls to panicked shrieking, feeling much less shaped and refined than other bigger death metal bands; however, this is a trick of the ear, because any bathroom extreme metal specialist will quickly find that nailing these particular inflections of vocals, which here contribute so greatly to the band’s overall effect, are subtle but clear in their difficulty.

Also, this band does not fear melody. Death metal is strange in that — for all the sub-subgenres like technical death metal, progressive death metal, no-frills death metal, melodic death metal, brutal death metal, and so on — the genre seems to collapse back in on itself at its peak performance, only to be best described again simply as “death metal.” Death metal inherently mixes the primitive with the technical, the straightforward with the progressive and avant-garde, the melodic with the atonal, the brutal with the rich, etc. Morbus Chron, as a testament to those dog years of the band when they seemed like the runt of the litter, clearly spent a lot of time listening to lots and lots of different death metal records to implement little spices across Sleepers in the Rift, which feels even now like a rich and satisfying compilation of death metal ideas. It found itself in good, comfortable company too: Repugnant had released Epitome of Darkness five years prior with Tribulation dropping their debut The Horror only a few years later; and, one year after Sleepers in the Rift, like-minded American death metallers Horrendous would drop their debut The Chills, fulfilling a similar role of deeply accomplished syncretic death metal.

The association with those bands is not incidental. Like the fractured Repugnant, and even more like the kinds of psychedelic/prog-rock transformations that Tribulation and Horrendous would undergo, Morbus Chron began to experience a metamorphosis. It seems that for bands of this level of accomplishment, only one studio album of a style is really tenable; across these bands, we can begin to see that singular record, which is most often the debut, serves more as a capstone to a lifetime of listening to and studying death metal albums which would then become the fundament of the group’s ongoing works, with each following album both reaching wider for interesting outside influences and also inward to whatever specific artistic voice each group may have to offer. Likewise, as Tribulation and Horrendous would move into weirding prog, Morbus Chron would as well, releasing a brief EP titled A Saunter Through the Shroud which signaled this future shift.

In fairness to the group, Morbus Chron did not release anything as crass as a denigrating press release diminishing their previous more traditional death metal work. Instead, they teased the value of this coming change of sound in the most musically admirable way possible: a quiet release of a small collection of new music with featuring a cover, plus sound so catching that it would be a shame to relegate it to a minor release. If Sleepers in the Rift is Morbus Chron’s love-letter to death metal before the overly serious and fun-hating streams of extreme metal fandom following the rise of black metal shook things up, then A Saunter Through the Shroud was a love-letter to its lifelong weirding impulse, the way death metal of the late 1980s and very early 1990s seemed to not quite know precisely what direction it should go, and so found itself sonically butting up against proto-black metal as much as high-minded but low-budget progressive rock.

The A Saunter Through the Shroud EP was, of course, just a sampler of where Morbus Chron would take these slowly mutating ideas; having caught the bug and found a receptive audience, it was only inevitable that next time they would strike deeper and with more certainty.

…

…

In storytelling we often have a pedagogical resistance to the implementation of dreams, be they a mundane dream sequence or the revelation that an entire story exists as a dream and not fact. This is not an altogether undeserved resistance; handled poorly, such a revelation saps the strength from a narrative, lessening its dramatic weight and consequence down to zero. And it is this lessening of dramatic consequence that we so balk at; the most common question we tend to ask as audience members (and even more so as critics, writers, and editors) is not, “What does this mean?” but more often, “Why should I even care?” The revelation that the events and content delivered did not even transpire in the realm of the real but in fact dissolved to nameless nothingness in the morning air feels too like a rendering-moot of the entire purpose of telling the story. It can feel as disrespectful as telling a politically powerful tale about abuse and subjugation and deciding instead to fixate on an aimless daydream instead of the real suffering surrounding it. And that sense of misplaced narrative choice, of privileging something ephemeral over something of historical, psychological, sociological and thus broader ontological value feels, to be frank, stupid. A waste.

Likewise, we see a parallel in political philosophy, which in the years following Marx has privileged more and more a material reality, be it the cruel proto-fascism of realpolitik or the liberatory fixation on material relations and access within socialist social and political theory. This is where we see a recurrence of motifs such as god being an opiate of the masses, a statement intended to say that the comforting irreality of god and the spiritual world sometimes dulls us like a dose of laudanum to the real material suffering and subjugation in the world around us, indefinitely delaying the liberation of ourselves and others for some unreal infinite joy that comes after death instead (granted, Marx meant this less as a statement of the total uselessness of faith and more of a potential and frightfully common negative situational use of it).

It feels, and not for a lack of cause, that feelings, perceptions, and issues that cannot be grounded in the material world, that of facts and matter and history and verifiability, are untrustworthy at best and a corrupt waste of time at worst, pointing us not only away from the right direction but striding us long toward a resolutely wrong one.

So this resistance to something like dream, which feels immediately like an element of the irreal rather than the real, makes an amount of immediate sense. The issue is that this sense-making falls apart the deeper we look at it. For one thing, dreams may not be ontologically real in the traditional sense — they may not be real events that happen with real material objects in real physical space to real figures — but they are phenomenologically real. Regardless of whether they exist out there in the world of space and time and matter and history and facts and verifications, they do exist inside, as experiences. And while it is tempting to write off the value of experiences over facts, we then quickly find ourselves in a position where things like mental illness have no value except as corruptions of the psyche. I am not advocating necessarily that neurodivergence (a real and necessary term to describe people such as those on the autism spectrum, who do not view the world wrongly so much as differently) be expanded to cover things like depression and manic fits, which have led me personally to destructive and sometimes explicitly suicidal behavior. But it is important to remember that experiences are real internally even if they cannot be properly verified externally, and that things like thought, dream, and memory are not ghastly supernatural things but physical, material, chemical/electrical actions that take place in the structure of the brain and thus carry real material consequences.

Thankfully, or perhaps horribly, we are not left with the platonic notion of two worlds separated by infinite space, one the actual/material and the other the real/ephemeral. And while the existential model — one that views the world (including matter itself) as nothing but a set of ephemera, all time-bound and designed to eventually cease existence and thus form a concatenation of hauntings of essences and histories and psychologies and meanings — is perhaps the most explicitly true, it is likewise the hardest to apply to things like art and daily life due to its density of ideas and exponentially increasing set of interrelations between objects, events, perceptions, and psyches.

Instead, a more workable model might look like this: there is the Actual world, the one of physical matter and events that happen inside of history and time, and there is the Real world, one of ideas and dreams and imaginings and anxieties and emotions, and there is a corridor between them that acts more or less like the demilitarized zone of thought/reality.

That corridor has a physical correspondent in the brain itself: it is a way to imagine the subconscious as an experience, a conglomeration of various processes that occur naturally in the brain but remain obscured from the frontal cortex, like decisions about the prickling of skin in the cold, or the way tremors can make us terrified of predators, or how sub-bass can cause anxiety, or the weird worming surreal logic of dreams. It also has a metaphysical correspondent in the liminal, that “dimensional bleedthrough” (thank you, Krallice) where fears and memories and joys and imaginings slip from that world of irreality to the world of reality; subconscious associations form between feelings, experiences, and objects in what can be viewed as the mechanics of symbology, or how we begin to associate thoughts and feelings with abstract symbols. Some are simple: the liminal association of hammers with power, for example. Some are more abstract: the marbled step as lost wisdom, or the vine for self-sacrifice and eternal wisdom. But functionally, while they may have different routes that cause feelings to encode to symbols and vice-versa in different ways, random firings of the brain picking up layers of meaning over time whether by rational means (i.e. ones determined by the frontal cortex, or the thinking mind) or irrational ones (the subconscious, emotional/experiential ones), they still acquire these meanings.

This is a very fancy way to say that dreams have value. Consider the primary mode of horror which embodies sometimes deeply abstract terrors triggered by images of rotting wood and rattling insects and squirming galaxies pulsing rich with fresh blood — and in that embodiment, those feelings in us flower out, bursting up through the soft loam of the liminal into the conscious mind where we confront these still caverns and wells of anxiety that linger in the dirt of the body. This is also the somewhat psychologically primordial mechanical function of both art and religion, a myth-making function of the mind that displaces those things which bury inside of ourselves in love and terror to abstract symbols that we graft onto poems and novels and songs as much as in the stillness of dreams. Art does a job that dreams seemingly can’t: art makes these inexplicable and otherwise meaningless hangups we all experience suddenly make emotional sense to one another.

The entire point of learning to write well, whether one is authoring instrumental music or a novel or a painting, is in finding a way to capture first the objects and experiences we find ourselves artistically hung up on, fixated on, and second, to make an audience emotionally experience what it is that goes on inside of us in the presence of those things. Telling people our dreams has always felt a bit shallow in comparison, which is deeply ironic since it is the more primitive and direct version of this same impulse.

Not everyone makes art, but everyone dreams.

…

…

Sweven was to be Morbus Chron’s second and last album. On one hand, this is deeply frustrating: Sweven is not only the band’s greatest work but also one of the greatest death metal records ever made, one deeply deserving of canonization even so shortly after its release. It is a progressive death metal record, but that designation would bring to mind sonic ideas not really present on the record. Sweven doesn’t truck as much in the technically demanding, odd time signature, riffy roar of groups like Demilich or Gorguts (both absolutely brilliant groups) as much as it appends late 1960s psychedelic rock to the broader base of death metal. In doing so, Sweven achieves a sound not unlike Tribulation’s Children of the Night, one that takes the early death metal approach of breaking the sonics of heavy metal down to their fundamental roots of dark psych-rock and layering over it the occasional knotted chromatic riffs and growled lyric to establish the death metal connection.

There is no shame, of course, in producing straight-down-the-road death metal, and groups like Cannibal Corpse and Immolation have provided us with decades of incredible records doing just that. But where those groups achieved canonization by perfecting the form and nailing down its fundamentals, Sweven becomes a necessarily canonical record in how it elaborates on those bounds while remaining resolutely death metal. There is no violent misogyny present on the record, no coded queerphobia or racism becoming more apparent with each listen such that the record you loved as a child becomes intolerably cruel and bigoted in the eyes of adulthood. Instead, it is Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd covering Dismember and Incantation, channeling that burbling weirdness that lingered at the fringe of death metal from the very beginning down the gloomy halls of psychosis and internal torment found in the bleaker spaces of psychedelic music.

Fitting then that “sweven” itself is an archaic and quite gorgeous word meaning “dream” or “vision.” Likewise, opening track “Berceuse” takes itself from the name for a form of lullaby. The album has recurrent riffs and melodies and is sequenced and produced to play like a single great breath of death metal, unbroken by the limits of track length. There is a waltz-like lilt to the music, which careens and bobs more than it thrashes and stomps. Morbus Chron, of course, can thrash about when desired, and there are certainly moments of more outright aggression on the record reminiscent of their older material, but Sweven for the most part feels like a lunar complement to the intensely solar Sleepers in the Rift, a record whose life was defined by replication of death metal idioms whereas its follow-up evaded them. Fitting, too, is the correlation of the names Sleepers and Sweven, offering the notion of their joint value.

Sweven seems to have no clear internal orchestrational organization, moving from section to section with rare repetition. Riffs repeat once, maybe twice, then depart, only to arrive again in some later track in a morphed manner such that you don’t immediately interpret it as a recapitulation as much as something eerily familiar. It moves sideways more often than forward, the riffs following a sort of dream-logic progression from one to the next. This long-form linear songwriting is a risky choice because (as has been seen by any number of bland and aimless psych or prog groups flooding those markets) it can often result in emotionally toothless music more obsessed with strange structure than good melodies and strong rhythms and other core fundamentals. Morbus Chron, however, is a death metal band at heart. Even if Sweven is undoubtedly one of the lightest death metal albums one could ever play (I played it once for a 70-year-old man who predominantly likes bad white-guy blues-rock and even he enjoyed it, likening it to a very heavy Beatles record), it is still driven by that core mentality of “riffs first and other shit later.” It doesn’t feel like the high-concept elements of Sweven drove its composition as much as the other way around, the dreamy nature of the hyper-extended album-length composition calling for nods in titling and art.

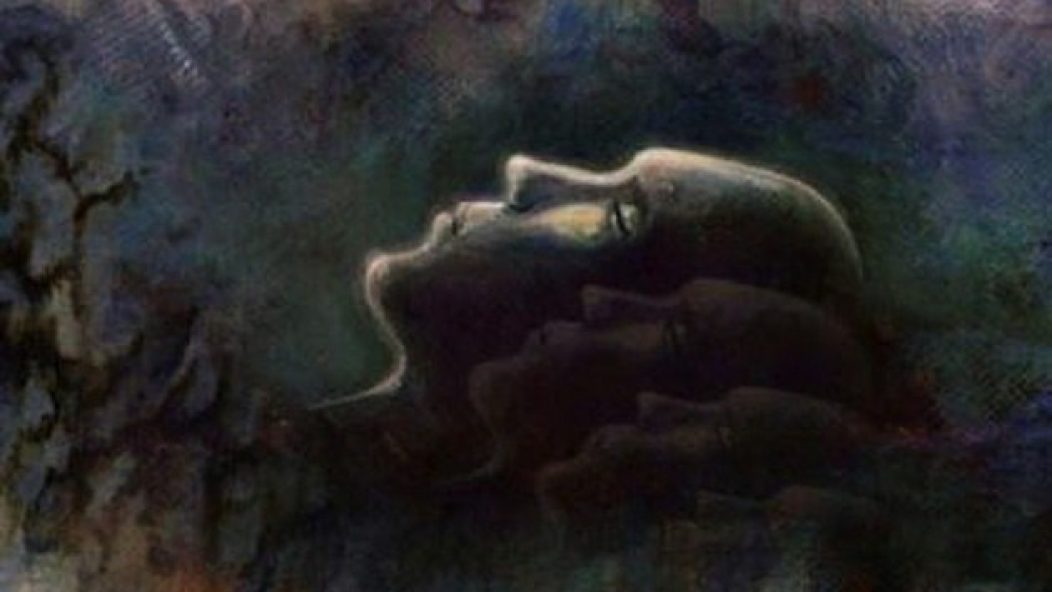

For all of Sweven‘s adventurousness, it doesn’t feel like a band turning their back or thumbing their noses at death metal either. It would be cheap and wrongheaded to refer to them as transcending its boundaries; if anything, the underlying notion of the record, embodied in the dream motif and the eerie art depicting a dreamer experiencing the dissociative multiplicity of psyche in dream, is to show just how small those limits within genre are. Morbus Chron, like other great and inventive bands before them not just in death metal but in any genre, clearly see their “genre space” not as a prison but as a set of tools and games which can be applied to any number of base sonic ideas. As much as I could comfortably present Sweven to psych-rock or prog fans as an absolutely great record in those canons, there would always arise the question of how heavy it was, as those psychedelic and proggy inflections have been inside of death metal since the days of Scream Bloody Gore and Altars of Madness.

Morbus Chron, like any great band, is less interested in proving that the genre in which they made their name is shitty and worthless; instead, they are interested in showing all the potential things that can be done under that umbrella that can still carry the sound and spirit but are presented in different manners. Likewise, like any truly great record, Sweven is not defined by those more cerebral or philosophical elements I laced this article with. For me, those are the thoughts that naturally germinate from this record; ruminations on the nature of dream and the irreal and its relation to the real, the way the world as we know it is a material matrix cut through with these fragmentary ghosts rising up from terror and memory and desire and phantasia. Heavy metal itself, be it doom or thrash or black or death metal, is built upon this embodiment of phantasia, taking surreal and hyperbolic stories and images and giving them flesh and life. And the great beauty of heavy metal is (like any great art): while we can wax philosophic about it and extract these strange and multivarious insights about the world, its constituent objects, and their relations, heavy metal itself is a much more pure experience.

Sweven is not a brainy record, nor is it a pretentious record. In the moment of listening to it, it is a haze, an opium den, a wizard’s wandering through a world made from dreams and the splashing whirlpool drowning the frightened screams. It is singular, small, experiential. But while it does not contain these thoughts, it effervesces them, fires them off of itself and into me, through me, like a solar flare licking the surface of a distant exoplanet. I hold its cover in my lap, big vinyl art staring back at me, and as I imagine my body experiencing the multiplicity of its central figure I enter a fugue where these thoughts pour out, snarl and concatenated like some cryptic dream architecture, some strange building with cruel angles and frightful corridors and stairwells and crenelations bursting from the flesh of the dream.

…

Langdon Hickman is listening to death metal. Here are the prior installments of his column:

I’m Listening to Death Metal #1: Opeth

I’m Listening to Death Metal #2: Atheist

I’m Listening to Death Metal #3: Ulcerate

I’m Listening to Death Metal #4: Gojira

I’m Listening to Death Metal #5: Tribulation

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon; check out Invisible Oranges merchandise on Awesome Distro.

…