Heavy Metal Be-Bop #1: Interview with Dan Weiss

. . .

INTRODUCTION

. . .

Heavy Metal Be-Bop is a series of dialogues about the intersections of jazz and metal. The genesis of is largely selfish: I want to gain a better understanding of my own tastes. In my work as a journalist, I cover a lot of jazz. I’ve researched the genre intensely for more than a decade, conducting dozens of interviews and schooling myself through close listening to records. At the same time, I’ll probably always consider loud, aggressive rock as my aesthetic home base. I grew up attending shows by Pantera, Megadeth, and Danzig before gravitating toward Hoover, Dazzling Killmen, and other intense and unusual post-hardcore bands. Jazz came later, and even as it consumed me, I never let go of my metal-etc. roots. For a while now, my listening time has been split evenly between these two styles. This week, I’m replaying Gorguts’ From Wisdom to Hate incessantly; two weeks ago, it was Be It as I See It, a beautiful new album by jazz drummer Gerald Cleaver.

I’m at a loss to explain this duality. Do I assault my ears with metal and soothe them with jazz? I don’t think it’s that simple. A lot of the jazz I enjoy (a 1969 Cecil Taylor bootleg I acquired a little while back, for example) is every bit as harrowing as the most brutal metal. Do I seek out the same qualities in each, then? Not always, since I relish tightness and precision in metal (e.g., Confessor drummer Steve Shelton) and looseness and fluidity in jazz (e.g., Tony Williams’ drumming on Miles Davis records like Nefertiti and Filles de Killemanjaro). Is my enjoyment of the two styles simply unrelated, then, no different than enjoying both burgers and sushi? I’m not sure about that, either, since I love to hear artists skillfully blurring the jazz/metal divide. To name a handful: The Mahavishnu Orchestra, late-period Black Flag, Last Exit, Little Women.

As I’ve attended jazz and metal shows, I’ve noticed that these demographics frequently overlap. When I spotted jazz pianist Craig Taborn at Jesus Lizard and Gorguts/Portal shows, it occurred to me that if anyone can shed light on the jazz/metal affinity, it’s the musicians in these styles. We know that John Zorn, Cynic, and others have juxtaposed jazz and metal for years – but are the genres cross-pollinating in other, less obvious ways? What metal bands are particularly popular with jazz artists, and vice versa? (On the latter tip, check out jazz picks from Ludicra and Agalloch drummer Aesop Dekker here, courtesy of NPR’s Lars Gotrich.) Can a single player excel at both? Is contemporary metal actively influencing contemporary jazz, and/or is the opposite occurring? Is there some subterranean connection between these aesthetics that stretches back to Mahavishnu’s seismic early-’70s fusion? Heavy Metal Be-Bop will address these questions and many more.

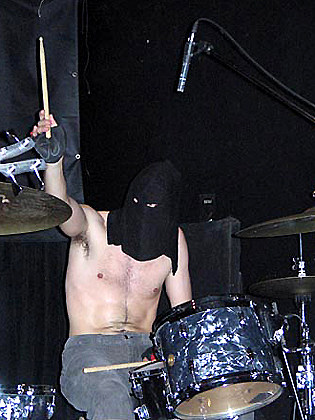

The subject of this debut installment is Dan Weiss. Doom connoisseurs might recognize him as the former drummer for Bloody Panda, in which he honored the band’s custom of playing shirtless, hooded, and excruciatingly slow. He’s also a jazz and tabla expert, and though he’s stopped performing metal in favor of those interests, he’s still a serious student of the genre. His compositions for piano trio sometimes reference metal, e.g., “Ode to Meshuggah”, which nods to the Swedes’ brain-teasing syncopation. But even when Weiss isn’t making direct allusions, you can hear the style’s subtle influence on his work: Timshel, an engrossing 2010 release, features eerie moods and knotty vamps that push metallic buttons without slamming on them.

Last month, Weiss and I sat down to discuss his history with metal and spin some prime examples of the style. Following the prescription of a great listening-to-music-with-musicians book, The Jazz Ear: Conversations over Music (by Ben Ratliff, another writer who has conducted a serious investigation of the jazz/metal link), I let Weiss pick the majority of the tracks.

I hope you enjoy this first installment of Heavy Metal Be-Bop. Please pass on any ideas you might have for future interview subjects, and stay tuned for another edition soon. Incidentally, the name of the column is a bit of a smokescreen; it comes from an ultra-chopsy yet largely nonmetallic jazz-funk record by The Brecker Brothers. I just like the sound of it.

. . .

INTERVIEW

. . .

. . .

Where did metal come into your life?

My earliest roots were The Who and Zeppelin and Hendrix. Then I moved on and evolved. Not to say I wasn’t still listening to those guys, but I was listening to Rush heavily, Yes heavily: progressive rock. Then in high school, too, I got into bands like Soundgarden and Faith No More. Right after the Rush/Yes phase, I heard …And Justice for All, and that was what did it. I remember hearing “Blackened”, and I was done. That was the record that opened the door to metal.

Before you joined Bloody Panda, were you playing rock and metal?

When I started really young as a kid, I was playing classic rock with my dad, and I had a band and we’d play stuff ranging from Faith No More to Rush to some jazz repertoire. So I definitely played rock before I played jazz. I didn’t really play in any metal bands coming up, just rock. And then I got the jazz bug big, like 14, 15, so I started playing a lot of jazz. So I didn’t really come into playing metal. My only real experience playing metal was Bloody Panda.

And in terms of your formal training, was it only in jazz and Indian music, or did you do some formal study of rock and metal?

When I started, it was rock. I guess there are some classes at Berklee, but that’s a tough thing to really study formally. But my teachers and I would go over some John Bonham and Keith Moon, when I was really young: 7, 8, 9, 10. I guess just listening to and analyzing the records would be the most formal study that I did.

Have you worked much with drumming techniques that are specifically associated with metal, like blastbeats and double bass?

Probably when I first got into Metallica, I remember buying a double bass drum pedal and messing around a little bit, but no. Now what I do, the tempos that I can, I’ll try to play a Meshuggah tune with one foot, the things that I’m capable of and not too super-fast. And blastbeats, just picking up what I can. I’ve never really put in so much time practicing that stuff at all. That’s more just kind of learned by osmosis.

You started off by getting into John Bonham, which has so much to do with power and then you got into jazz, which has so much to do with finesse. And just from seeing you play the other night, it’s obvious that precision, low-volume playing is a big priority for you. So when you first got into jazz, did you see it as veering off onto a different path, or did you see a hidden commonality between the styles?

Good question. The first thing: I really love playing quiet and soft, but there are a couple [jazz] groups where I play pretty hard, like at the end of the gig, I’m drenched in sweat. Like with [Dave] Binney or Rudresh [Mahanthappa], I’m hitting – I’m really hitting the fuck out of the drums. I’m really hitting hard. So I like both.

When I got the jazz bug, I did kind of veer off into that. What really attracted me about jazz drumming was the subtlety and the nuance of the different sounds that you could employ, and when you’re playing rock, the dynamic range is a lot thinner. So when I did get into jazz, I kind of turned my back on the whole rock thing for a while. I didn’t have my nose up in the air, but I had blinders on. It was jazz, and that was it. And it’s not until I hit maybe 20 or 21 that I go back and re-embrace the rock thing, ’cause I didn’t really listen to it for a long time. And that’s when the whole embracing and accepting the rock thing and the metal thing into what I did – I learned to embrace that.

Do you remember what it was that led you to come back to it?

I never really checked out the Beatles as a kid. And then in college, I started checking out the Beatles, and I think that was the trigger. I was like, “Wow, I can’t believe I never checked this band out”. To me, it was just pre-’64, that sound, and then I heard Abbey Road or the White Album, and then it was like, “Oh my God”. That was probably the trigger, and I went back to everything – Rush, Zeppelin, then I heard Meshuggah at that time, ’98, ’99, or something – and that opened another door. So all these little windows and then the window gets cracked, and I’d go into this world, I’d go deep in, but it just took one little thing.

What was it about Meshuggah that intrigued you?

Definitely the rhythm – just the rhythmic aspect of the band, really on such a high level, rhythmically, what they were doing. And the sound, too – I remember listening to it in my car. The first record that I got was Chaosphere (laughs), and I was just floored by the sound, like (punches hand: pow!) just in your face, and the more and more I listened to it, I would see how the vocals were really connected with the the rhythm of the song, just so intertwined. And I was studying Indian music, too, at that time, so the beat cycles that they were using were fascinating to me, but it never lost the groove. Some metal bands for me, the groove is kind of weak. Meshuggah, to me, that’s really what it’s about – the groove, really strong – and seeing them live is a testament to that. Even with all the shit that’s goin’ on and all the crazy meters, the backbeat’s really there. I love it. It’s like soul; Meshuggah’s like soul.

. . .

Dan Weiss Trio – “Ode to Meshuggah”

. . .

When did you hook up with Bloody Panda?

2006, maybe?

And between the time you got back into metal and then, were you checking out a lot of new stuff?

Yeah, at that time, I was really immersed in probably everything I listen to now. But you know, I wasn’t exposed to much doom metal, so that was another door that opened for me, Bloody Panda. So when I started with them, I [hadn’t heard] seminal bands like Burning Witch or Sleep. I had no idea about anything like that. So then I was starting to check out those bands, the doom bands. And I liked that stuff a lot, too.

In a way that stuff comes out of Zeppelin, but also Black Sabbath. Were you grounded in Sabbath at all?

Sabbath, yeah. It’s all Sabbath. You could really say that Black Sabbath started all metal movements, right? But definitely doom. If you listen to the first tune on Black Sabbath’s Black Sabbath, that’s doom (laughs). That’s what it is. So there was a lot of bands that, playing in Bloody Panda, they exposed me to, and they’d say, “Check this out; check this out”. I really like that stuff a lot.

So how did Bloody Panda find you?

The drummer that was originally in the band, he liked my jazz playing, so he took the bass player, Bryan [Camphire], to see me play, and we talked and he found out that I liked metal, and then the drummer moved or he couldn’t do the gigs. I don’t know exactly how it happened. [Bryan] probably gave me some music and said, “Check it out”. I love them. I’m probably one of their biggest fans now. I just couldn’t do it anymore physically. It’s too much in this life to take on all that stuff: play tabla, play in a jazz setting, play in a metal band. I just made a decision to appreciate it from the outside. I can’t do it.

When you were juggling these two things, I’m very intrigued by that, because I think it’s very uncommon for someone to be able to authentically play jazz and then go over and authentically play metal. Is it possible?

It’s possible. I’m trying to authentically pull off tabla, too, so it’s just a tough balancing act. But I think it maybe just needs to be in your blood. It was such a part of my upbringing, that stuff. Early on, I was so exposed to it and listened to it so many times, and I loved it so much. I think it just takes a willingness to want to do it. I don’t know if many people would want to do it. I know maybe a few guys. I just made a decision: I’m gonna go in with this band, Bloody Panda, and I’m not gonna approach it like a jazz drummer. Maybe I’ll bring some elements that wouldn’t be brought in otherwise, but I’m a metal drummer in this band.

But if someone asked me to join a death metal band, there’s no way I could do it, because it’s beyond my technical limitations. I couldn’t play a blastbeat for four or five minutes. There’s no way. But, luckily, a doom metal group – I had the technical facility to be able to pull that stuff off, ’cause it wasn’t super, super technical.

. . .

An introduction to Dan Weiss

. . .

You said that you had played some classic rock growing up, but not necessarily metal. It must have been interesting to have all this experience as a metal listener but not so much being onstage doing it. What surprised you about it? Or what did it feel like to actually do it?

It was really fun. That’s the biggest thing I could say about it. I would really look forward to the shows, maybe more so that anything else. I would really look forward to playing those, ’cause you kind of know what’s gonna happen in the tune, everything is through-composed, so it’s a different kind of thrill than jazz improvising, where you don’t know what’s gonna happen. But the sound and the energy is so powerful that it really was fun, just seeing people in the audience headbang and stuff like that. Then being able to play that hard, just hitting really hard. Ultimately, that’s why I couldn’t do it anymore. It was just too tiring, too taxing. I fainted after one gig.

I saw you guys in 2006 or 2007, and obviously Bloody Panda is so theatrical, with the costumes and all that. That, too, is such a huge gulf from jazz. 99 percent of the time, jazz is presented as this unadorned, raw thing, where people play under their own names, you can see their faces, you talk to the audience. What was that like, moving between those two styles of performance?

It’s funny, because my girlfriend is always saying, “Jazz has got to be more of a show, it’s got to be more of a theatrical thing”. The past few weeks, we’ve been talking about that. To answer your question, the venues we were playing with Bloody Panda weren’t really big enough to be like, “Here’s your green room; here’s your dressing room, go backstage, and then go back there after the gig”. The audiences were small, so after the gig, I’d be tearing down and maybe talking to people in the audience. So it was kind of similar.

Did you enjoy the costumes and all that?

It was fun. I enjoyed playing with a mask on. I enjoyed playing without my shirt. It was fun. Yeah, I guess ’cause it was such a different type of thing than jazz. I’d never get a chance to do that. I mean, I could, but realistically, when would I ever get a chance to put a mask on and play without a shirt? Yeah, so those were all fun things that I liked, apart from the music and playing. I found it fun, those things that I didn’t get from jazz.

. . .

. . .

In terms of leaving Bloody Panda, it seems like it was almost a preservation thing, like you’re a career drummer and you felt like you were abusing yourself doing this. Or was it more like choosing because you didn’t want to be spread too thin?

Definitely both. I got this big cyst from playing. It’s still here (points to wrist). It was preservation. I was also thinking of the tabla, too, as well. I would get blisters from playing [in] Bloody Panda every time, and my hands would swell up. It was preservation and spreading myself too thin, and I just made a decision: I’m gonna just appreciate it as a listener and incorporate some of the elements of the music into either my drumming or my composing, and I’ll be happy with that. I don’t need to go into playing in a metal band. So I think it was a good decision. I was happy with it. Although I really did enjoy playing that music, and I’m a big fan of that music, both before and after I was in the band. It’s great, great music.

If metal is not coming through literally in your music, where does it come through?

I guess when I drum sometimes, you’d definitely be able to hear it. Other than that, a lot of the aesthetic of death metal drummers, even going back to Lars [Ulrich], Gene Hoglan, Steve MacDonald from Gorguts, even Neil Peart. The way that they would shape drum patterns and make them really part of the song, they’re compositions within themselves. If you analyze what Gene Hoglan’s doing or what Steve MacDonald was doing, they’re orchestrating. They’re really orchestrating on the drum set. Jazz drummers of course orchestrate, but [metal is] a different thing, because it’s a more through-composed orchestration that carries throughout the tune. That’s one thing I took from metal, just drumming – that idea of it’s OK to have that approach. It doesn’t always have to be this changing, evolving thing within a song. In a context of improvised music, it could be a very well-thought-out drum pattern in maybe a free section of a song, of a jazz improvised tune.

Yeah, listening to your work, I’ve noticed that there are some tracks where the imperative is not improvising. It’s just a written piece of music. Sometimes the other two are vamping, and you’re soloing, but there are parts of it where it’s not just “Let’s play the head and get to the solos”. It’s more about, “This is a piece of music”.

100 percent. Exactly. For me, it’s not always about improvising. And some tunes, the parameters of the improvising are very narrow. Maybe Jacob [Sacks, pianist] will play the melody, and the improvising will be ornamenting the melody a little bit each time, like that tune “Florentino and Fermina”, for example. There’s not like a solo section, but in the repetition – since it’s repeated so many times. That or a tune like “The Day After Tomorrow” off the first record, improvisation takes on a new meaning. It’s not really blowing on a form, but since you’re repeating these melodies often, improvisation has to come a different way. So maybe it will be ornamentation of the melody, slowing down or speeding up the tempo of a melody, things like that. So the parameters are smaller in some tunes, where there’s not really a form: “This is the head, you’re gonna blow here, and then you’re gonna come back to the head”. And I guess I owe a lot of that not to just metal, but to just straight-up Western classical composing, which I get a lot of inspiration from, too – just trying to strike a balance between composing and improvising.

. . .

. . .

Do you find yourself running into other jazz players that have an interest in metal?

I could definitely name some musicians that are into metal. Have you heard of [pianist] Matt Mitchell? He’s way deep in there, and we have a duo. I guess you find like-minded people, and that’s a common bond that just draws you closer to the musician. But the percentage of jazz musicians that are true metal lovers I’d say is pretty small. I know [guitarist Ben] Monder loves Meshuggah. Trevor Dunn, who obviously plays both jazz and metal – that’s a guy who’s successfully done it, really done it. If I had to say one guy who’s done it, I’d say Trevor, from Mr. Bungle to Fantômas and all the stuff he does jazzwise. But yeah, I think it’s a pretty small percentage. Some people, they’ll like Meshuggah or stuff like that, but they won’t go really deep.

What about the other way around, metal people who are into jazz?

I guess I haven’t run in that circle so much, so I can’t really so, but [the Bloody Panda] guys were super open-minded. I wouldn’t say they were jazzheads. They were more interested in music of different countries and really open-minded about that stuff: Javanese stuff, Japanese puppet music, stuff like that. But I don’t think I’m really qualified to stay, in terms of metal people, how much of a jazz bug they have. I know that on Meshuggah’s Destroy Erase Improve, they list a lot of their influences, and Chet Baker was one of them, which I thought was really cool.

You said you’d had contact with the guys from Gorguts, right?

Yeah, I met “Big” Steeve [Hurdle, guitarist on Gorguts’ Obscura, also of Negativa] up in Montreal, and we stayed in touch since then, and then I got in touch with Luc [Lemay, Gorguts guitarist and vocalist]. I sent him some stuff of mine, and we were talking about playing, but it just never panned out. Big Steeve and Luc, they joined that band Negativa. I don’t know what happened; I was really into that EP. But metal guys, I’m telling you, as you probably know, they’re the sweetest guys. You go to a metal show, and they’re so polite. Nobody would think that, just looking at a group of metalheads, someone on the outside.

What was Steeve Hurdle like? Did you guys have a dialogue?

We would talk about music and what each other was listening to. I remember there was a period where I was really into the Cocteau Twins, and he was into – I don’t remember what band, but he was into stuff in that same vein – so it was interesting to share what we were into. He wasn’t listening to metal, really. He was listening to more shoegaze or ambient stuff – a really open-minded guy.

Since we talked about groups like Naked City and Mahavishnu, I wanted to ask: Do you think it’s (a) possible or (b) interesting to think about fusing jazz and metal? Has it been done successfully and if so, by whom?

I guess what is the definition of “successfully”?

I guess to me, when I think about something like Naked City, it kind of leaves me cold, like an “A + B” kind of thing, whereas something like Mahavishnu seems to actually fuse the aggression of proto-metal with the improvisational excitement of jazz. I’d call that successful, but that’s one of the only ones that I can think of. That’s basically jazz-metal.

Like maybe the more fusion element of jazz, and metal? Do you know Zs?

Oh, sure.

They’re not jazz at all, but it’s an acoustic group and there’s a metal mentality. There’s a band out of the UK, Bilbao Syndrome – it’s basically a metal band, but the frontguy is a jazz keyboard player. He plays Rhodes in the band. When I first heard them, I was like, “Wow, that’s great, that’s killing”. They’re from Leeds, I think. Again, if you heard it, you’d think straight-up metal, but the background of some of the people, they’re jazz musicians, like the keyboard player – I can’t remember his name. But he’s a jazz musician, playing the Rhodes as if it were a guitar. I’m trying to think of more jazz bands… There’s some Naked City stuff I like; other stuff, I’m with you. I really like their version of the theme song of Contempt. I’m a big Joey Baron fan.

. . .

Joey Baron plays blastbeats with traditional grip

. . .

Do you think his bridging of that divide was authentic and true to both?

I love it, but I wouldn’t call it metal drumming.

But there’s something interesting to that. Like to see Joey Baron playing a blastbeat with traditional grip, it’s fascinating, but it’s not – I don’t want to use the word “real” to qualify it, but it’s not how a metal person would play.

And that’s OK for me, sometimes, as I’m sure it is for you.

Sure. I think purity is – that’s dubious praise to say something is “pure”.

I’ll listen to shit like New York Art Quartet, and I’ll feel like that’s more metal than some metal. And then I remember doing this summer program at Berklee when I was in high school, and one of the drum instructors played Sonny Payne with Count Basie, and that’s metal, too. I remember hearing that and thinking, “That’s metal”. He was playing just a straight, loud, really quick bash beat with Count Basie. So sometimes I just get confused by definitions. Sometimes I really don’t care. It’s more about the honesty of the music. But I definitely feel that, yeah, sometimes there’s some gimmickry with that, just the fusing of elements.

Ben Ratliff wrote a piece in the Times a few years back where he argued that although jazz and metal don’t have a lot in common on the surface, they’re both in a similar place right now, where some very experimental and difficult ideas are receiving a lot of support. Do you see that parallel at all?

That’s interesting. I never thought about it. I can think of a really basic similarity now: There’s just so much of each. There’s so much metal going on right now, so much jazz. There’s so much good of both. There’s so many metal bands out that are good. So many jazz musicians, ideas… It’s a fertile time. It’s like oversaturation. I don’t know how people… I’ve just been thinking about music vs. audience percentages. I wish there could be more audiences for both. I feel like there’s access to so much, that fans are so spread thin, there’s few things that have a real following. That’s a similarity I can think of between jazz and metal now: just the abundance of music.

I hate to sound cliché, but it really goes back to what Duke Ellington said: “There’s good music and there’s bad music”. There’s so much metal I hear that I don’t like, so much jazz I hear that I don’t like. But I’ll listen to Gorguts or Meshuggah or Miles Davis, and it’s the shit. It’s simple: it’s just good shit.

. . .

LISTENING SESSION

. . .

Metallica – “Blackened”

(Starting at 2:44)

. . .

Why don’t we go from where I really started, which is “Blackened”?

Just Lars’ placement of these little jabs (mimics fills from 2:44–2:48, turning head each time as if discovering something). Let me go back to that little fill I just played. There’s a universal language in music. It could be metal, it could be Indian music. To me, he’s reeling you in there. He’s teasing you with that. And same with some tabla compositions. That kind of tension and release – it’s kind of like a child playing ball. (Rewinds to the kick-in fill at 2:51.) “Okay, I’m gonna go in now”. There’s that universal language. It could be metal; it could be anything. Just all those kinds of aesthetics that carry over. Just that moment, that hanging moment between the kick-ins. It’s very spotlighted. (Mimics fill at 3:14.)

Have you done a lot of playing along to this? Do you have the fills memorized?

Oh, yeah. When I was younger, I did. Every drum hit on this record is internalized. There’s another one. (Points out fill at 3:34.) (Points out guitar lead at 5:12.) That’s a resignation right there. I’ve always felt like that, like he’s resigning to something. (Rewinds: mimics slumping forward, giving up.) “I’m done”.

(Mimics fill at 5:21.) I love the way they keep turning the beat around here (5:32 and on) Perfectly placed China [cymbal] (5:49). Total Neil Peart. And just to be a drum geek. So now the last verse [“Smoldering decay / Take your breath away”] is happening, and he’s putting the crash in there. Now let’s go back to the first verse (rewinds). It’s not there. So that’s just development. It’s an aesthetic thing. You’ll definitely hear Neil Peart do those kind of things. It’s just a cymbal crash, but it’s really nice. There’s a care for that. It’s not just going back into the same thing. Just that little added something (Mimics fills at 6:03, 6:27.)

. . .

Meshuggah – “Electric Red”

(Starting at 1:45)

. . .

(Pulls out notebook with rhythms transcribed in shorthand.) I geek out over Meshuggah, so I really try to figure out what’s happening. This is a detailed analysis of what’s happening, and the shit that’s going on in this tune is absolutely insane. (Shows me notebook.) That’s hard to read, but the way they’re breaking this up is very, very interesting. But it’s all against the backbeat. Normally you’d be breaking a cycle into 32 beats. This section, the cycle is 31, and it’s absolutely crazy. So it starts… there (1:45). I hear this part as three measures of eight beats plus one of seven. Absolutely nuts.

. . .

Gorguts – “From Wisdom to Hate”

(Starting at 0:45)

. . .

(Exhales as if hearing something especially harsh during opening section.) This is an example of that through-composed drum part. It really had a huge influence on me. It’s the B section (starting at :45). That’s a long one. It’s a 48-beat cycle, but it’s broken up 11, 12, 13, 12, and throughout that cycle, the drum part is basically a 48-beat drum pattern. It really opens things up. You can hear just a lot of thought went into that part.

I like [that] the blastbeats and double bass aren’t constant. They’re all chopped up.

I hear you, I hear you. That [constant double bass] can get old really quick. Yeah, From Wisdom to Hate‘s gotta be top five metal records, easily. I just like the raw passion. Like great hip-hop – the raw, raw shit. It’s all kind of the same. It’s just like an energy.

. . .

. . .

. . .

Hank Shteamer writes for Time Out New York, blogs at Dark Forces Swing Blind Punches, drums for STATS, and wrote a book about Ween.

. . .