So Grim So True So Real: Arch Enemy

…

So Grim, So True, So Real offers a new way to think about a given band’s discography. In this feature, we will highlight first, the low point in a band’s body of work (So Grim), and then the album which, to the best of the IO team’s estimation, most people hold in the greatest esteem (So True), and finally one album which holds up as the best listening experience, regardless of what fans and critics insist (So Real).

…

It’s not black metal. It’s not death metal. It’s not thrash metal. It’s not doom metal. It’s not progressive metal. It’s not metalcore. It’s not nu-metal.

It’s metal.

Arch Enemy graces glossy magazine covers. They don fancily obvious duds for their high-budget music videos. They nail top-ten positions on (European) charts. They’re a metal household name, a veritable mile-marker that most never get close to reaching. People argue about which Arch Enemy record is the best; they don’t argue about which is the worst. This band has ten full-length albums over two decades and yet they still (somehow) maintain relevance. They’re known for raw riffs, soaring solos, and charismatic choruses, digestibly packaged and doused in groove. No one in the metal media has really questioned Arch Enemy’s authenticity, and why would they? They were born to rule with pure energy under majesty’s spotlight. Now, they even have Jeff fucking Loomis.

…

…

But holy hellfire, does current Arch Enemy desecrate all which once brought them greatness. They’ve become a bait-and-switch act: nabbing you with one or two catchy throwback licks only to bore you with a glut of oversaturated choruses and hyperbolic stage antics. The band has devolved, shedding songwriting skills for a hapless reliance on packaged beats and redundant kicks. Besides, Loomis didn’t compose any of this anyway. That’s not to say Michael Amott is insignificant, or talentless. Au contraire, he helped mastermind that suave aggression for which the band became known. It’s just that outside forces probably weighed upon the band during particularly challenging times, spoiling inspiration. Maybe they tried to fit a mold they helped create, resulting in a deformed and defective representation of their former selves. Or, maybe it’s the plain fact that Alissa White-Gluz isn’t Angela Gossow.

Easy answer to all of this: it was the bacterium of super-popularity. Medium answer: maybe they should’ve stopped after, say, Rise of the Tyrant (2007). Hard answer: maybe metal just sucks. Real answer: this writer is out of touch with modern metal and only cares about the the more obscure “classics” when it comes to popular bands. These all may actually be true, to different extents at least, but at least we’re having this conversation. So, take this into consideration: Arch Enemy is no longer the band willing or able to quote a film like Caligula (1979), which Roger Ebert called “sickening, utterly worthless, shameful trash.”

He wasn’t wrong; likewise, early Arch Enemy had some grit. Since then, it’s just been a process of polishing it all off, leaving a gleaming surface but flattened texture. For some, this increases the band’s appeal — let’s call it curb/video appeal — but for actual digestion, the nutritional value is greatly diminished. Predictability, too, becomes a serious downfall: we all know what the next Arch Enemy album will sound like. It’ll have groovy single-note verse melodies, climactic vocal-led choruses, and pristine production value, all familiarly arranged and neatly presented. What it won’t have is any fresh surprises, the wellsprings of real energy from which Arch Enemy used to draw their trademark smooth aggression. Replication is a manufacturing process; invention is an artistic one. Arch Enemy may be great manufacturers nowadays, but their product has become, well, flaccid and outmoded.

…

…

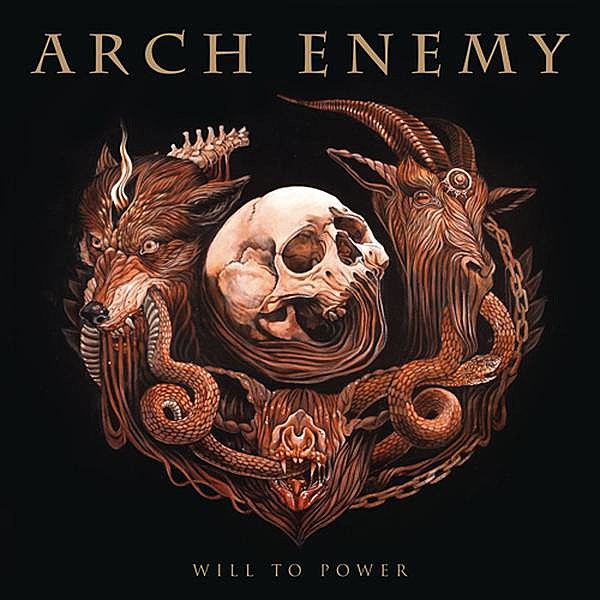

So Grim — Will to Power

Essentially, Will to Power is the soundtrack to discovering at 2 a.m. that the chips in the pantry are stale but sadly eating them anyway. Khaos Legions (2011) was near-expiration but still edible; War Eternal (2014) warrants a mulligan (maybe) due to the lineup shakeup the band had just undergone. As a desperate retry, Will to Power tastes like an older Arch Enemy album, but with the sharp, instrumental edge replaced by dreadfully boring rhythm sections designed solely to showcase a mediocrely theatrical vocal performance. The effort is half-there, perhaps its worst sin, partially because they didn’t utilize all their talent (ahem, Loomis), and also because they tried recreation instead of reinvention. Maybe the question was: “how can we rehash old Arch Enemy, but with these totally new and totally different ingredients?”

The answer isn’t to arrange everything as it was before and expect it to operate properly. New combinations need to be formulated, experiments need to be conducted. Will to Power was written as if Arch Enemy knew one particular formula would work; indeed, they had nine albums’ experience already, thus the confidence. Experience can’t replace intrepid exploration, though — sometimes prior knowledge can spoil the treasures of a journey — and with fresh talent, there were so many opportunities to be, well, Arch Enemy 2.0. Despite its seemingly slick user interface, Will to Power lacks functionality with its recycled song structures and annoyingly repetitive attempts at being simultaneously balladic and razor-edged, a defining balance better struck over a decade earlier.

This album doesn’t have to be a gravestone. Arch Enemy has the chops, but do they have the soul?

…

…

…

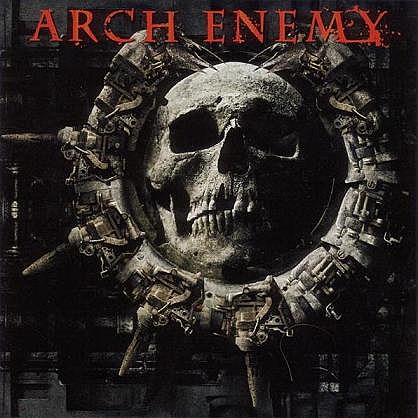

So True — Doomsday Machine

They had the soul, and following it led them to Doomsday Machine (2005), a cross-section of commercially viable but refreshingly on-brand Arch Enemy. The band’s “bigness” didn’t spoil their approach here; in fact, it bolstered it, making it truer. Tracks like “Nemesis” with its “hey, hey, hey!” crowd-chanting samples would have been utterly corny if written without supplementation from the Amott brothers’ wicked guitarwork. Perhaps the idea was to create memorable melodies which could be juxtaposed by simple, trademark choruses. Song structures may not have varied wildly — some faster and meaner than others, but predictably so — yet the actual content within the framework did. The result was something digestible, but far from bland. It was also timeless: a carbon copy of this album simply wouldn’t work today.

…

…

It’s not that prior albums were prototypical — surely Arch Enemy had found their voice long before. But until Doomsday Machine, that voice didn’t make as much sense as a larger-than-life projection. In some ways (none negative), this is to say that Doomsday Machine is the first Arch Enemy record fit for casual listening. It pleases in the background not because all the still-impressive foreground detail opens up that gateway, but because said detail is easily moved aside to reveal a pure catchiness. With this record in particular, there’s no “hook” to being hooked: once you’re enraptured, you’ll soon be presented with plenty to dissect.

…

…

…

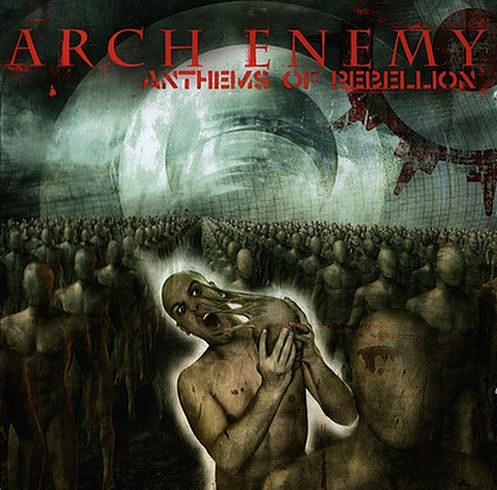

So Real — Anthems of Rebellion

If the well-balanced Doomsday Machine can serve as a reference guide for all Arch Enemy, the preceding Anthems of Rebellion (2003) benefits from a narrower approach: be lean, be mean. This album contains such little fat that, at first listen, it may sound somewhat flat, all horsepower but no torque. While the chunkiness of later albums hadn’t been fleshed out yet (especially guitar-wise), Anthems of Rebellion sought impact through more tactical means. Rippers like “Leader of the Rats” and “Despicable Heroes” relied shamelessly on simple (but fast) power chord progressions which synergized beautifully with Gossow’s hollow and harrowing bark. The album wasn’t without its more balladic moments, though, showing that lighters-in-the-air drama and pit-worthy aggression needn’t be mutually exclusive.

…

…

Anthems of Rebellion‘s “realness” stems from an imbalance, actually: the guitars take ultimate precedence. While the guitarwork on Doomsday Machine is noteworthy, it plays a relatively smaller role there (to that album’s particular benefit anyway). Arch Enemy’s real “anthems” are ones which make you want to pick up a guitar regardless if you’ve ever played before — if the Amott brothers weren’t already on the map, they were there now due to their dual riffwork on Anthems of Rebellion. Their silky mixture of technicality and grooviness made learning these songs challenging without ruining the endgame; and of course, the solos were bombastic and irreplicable.

This album can be thought of as a culmination of sorts: the preceding Wages of Sin (2001) was the band’s test-run with Gossow at the helm. It’s a remarkable album for sure, but not as balanced and professional as Anthems of Rebellion; it was more exploratory than definitive. Like many bands, Arch Enemy took their time to find their voice, quite literally trading one for another. The first time this occurred (from Johan Liiva to Gossow), it presented a radical but ultimately beneficial shift in the band’s aesthetic and output. The second time this happened (from Gossow to White-Gluz), something was lost. This isn’t the fault of White-Gluz by any measure, even if you think her performance is just mediocre. Rather, it’s all about positioning and timing: Arch Enemy “came into their own” during the Gossow era, and that fact can never be revoked.

…

…