God, Man & Flute Solos: 'Aqualung' at 45

…

If you’re reading this, odds are you’re more than just a casual fan. Hearing someone say, “I’m not really into music” sounds the same as, “I’m not really into food or shelter,” (to this writer, anyway). We tend to have similar habits when it comes to processing our passion: organizing physical collections to the point of obsession, encyclopedic knowledge of lineups and discographies, and perhaps most significantly, matching memories and milestones to bands and albums. You might struggle to recall your grandmother’s birthday, but I guarantee you remember the first album you bought with your own money. Maybe it didn’t age well, or it’s downright embarrassing, but you know what it is and why you bought it.

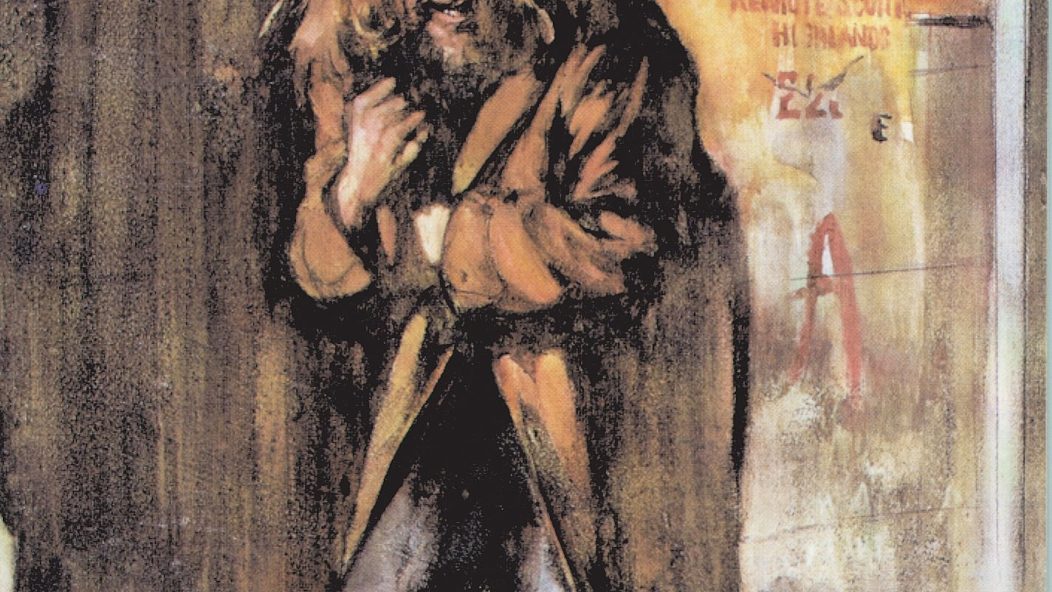

I got lucky: Jethro Tull‘s artistic and commercial breakthrough Aqualung was my first solo purchase, and it sounds just as good today as my dad’s vinyl copy did playing on the family stereo almost 30 years ago. One of my earliest non-Sesame Street musical memories is pestering my mother to play “the song with the snot!” (the title track: “Snot running down his nose/Greasy fingers smearing shabby clothes”) and dancing around like children do, unaware for about a decade that the song was about a vagrant pedophile. Fast-forward to 11 years old, already wearing out the dubbed cassette I made of my only CD–Tull’s M.U. best-of collection, a Christmas gift–and I have a gift certificate to the music store in the mall. Theology and its relation to society and the individual might have been a few grade levels away, but suburban prepubescent me was more than ready to rock and roll.

Though it’s still widely regarded as a concept album, Jethro Tull mainman Ian Anderson has shot down that notion repeatedly through the years; some of the tracks do have similar lyrical themes, but there is no central story or idea tying the album together. It’s also quite musically diverse: “Aqualung,” “Locomotive Breath” and “Hymn 43” (the album’s only single) are heavy, riff-centric rock staples while short acoustic segues like “Cheap Day Return” and “Wond’ring Aloud” serve more as bridges between the longer, more fully-arranged songs.

The first half of the album revolves around some character sketches conceived by Anderson and his wife Jennie, while the latter songs–which is where the ‘concept album’ impression comes from–deal with philosophical musings on man and society and their relationships with organized religion. These were somewhat heady topics for a rock band at the time, predating ambitious projects like Who’s Next and far removed from the lyrical inspirations of someone like Mick Jagger or Robert Plant. (Coincidentally, Zeppelin were recording IV next door to Jethro Tull in Island Records’ new London studio at the time).

After beginning their career as a more blues-oriented band, Tull had evolved into a frontrunner in the nascent prog-rock genre along with countrymen Yes and Uriah Heep by the time of Aqualung‘s recording. Anderson’s prodigious talent as a flutist (while ostensibly hilarious) added a unique element to the album, and his solos on “Locomotive Breath” and “My God” are indubitably amazing. Other arrangements included recorder, mellotron, male choirs and orchestral accompaniment. Aqualung‘s impact on prog rock still resonates, most notably with acts like Opeth, Tusmorke and Porcupine Tree (whose Steven Wilson remixed the album in 5.1 surround sound for its 40th anniversary) and across the metal spectrum with bands as diverse as Iron Maiden, Overkill and Clutch covering tracks from the record.

Jethro Tull continued an impressive streak of albums throughout the ’70s and into the ’80s, infamously robbing …And Justice For All of Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance at the ’88 Grammys with Crest Of A Knave. There’s a certain schadenfreude to hearing metal fans still complaining about this, especially those that weren’t born yet when it happened. So go ahead, make fun of me and my boring dad classic flute rock. After 45 years, we’re still doing just fine.

…

…